CHAPTER 6 Gastric wedge resection

Step 1. Clinical anatomy

♦ Gastric wedge resections may be performed for gastric tumors such as early gastric adenocarcinoma (lesions <25 mm in size), gastrointestinal stromal tumors, or other gastric tumors.

♦ Wedge resections to establish a diagnosis may be indicated if other less invasive diagnostic modalities have been unsuccessful.

♦ Wedge resections may also be performed for palliation of symptoms such as tumor hemorrhage for otherwise advanced, unresectable gastric neoplasms (for instance, in patients with distant metastatic disease).

♦ Tumors located at the GE junction or along the pyloric channel may not be appropriate for wedge resection because of the risk of luminal narrowing and may be more appropriately treated with conventional open or laparoscopic anatomic resections.

♦ Tumors along the lesser curvature may involve one or both vagus nerves. If both nerves are divided as part of the resection to achieve oncologically appropriate margins, pyloromyotomy or pyloroplasty may be required.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

♦ The indications and contraindications for laparoscopic gastric wedge resections are similar to those for any open gastric resection.

♦ Patients who have had significant upper abdominal surgery with resulting dense adhesions may not be candidates for a laparoscopic approach, although a diagnostic laparoscopy may be performed at the beginning of the procedure to determine the feasibility of such an approach.

Patient preparation

♦ Gastric tumors appropriate for wedge resection are generally identified either endoscopically or radiographically during workup of nonspecific upper abdominal symptoms, gastroesophageal reflux, obstruction/early satiety, pain, or gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

♦ On upper endoscopy, tumors generally amenable to a laparoscopic wedge resection are submucosal lesions with an intact mucosal layer. Those that appear mucosal-based or ulcerated may not be appropriate for a wedge resection based on histologic diagnosis, and the planned approach should be reevaluated.

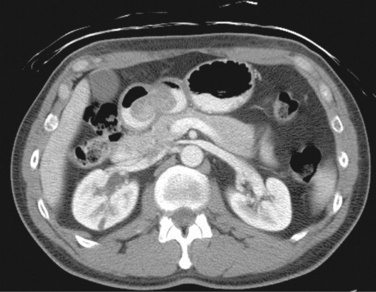

♦ On radiographic imaging, such as computed tomography (CT), tumors may appear as well-encapsulated or infiltrative lesions within the gastric wall or as exophytic lesions protruding intra- or extraluminally (Figure 6-1). Presence of extensive lymphadenopathy may suggest either lymphoma or gastric adenocarcinoma, necessitating a change in treatment.

♦ Additional imaging and laboratory studies for cancer staging may be ordered based on confirmed or suspected diagnosis.

♦ Endoscopic or image-guided fine-needle aspiration or core needle biopsy is indicated if the differential diagnosis would significantly change management. For instance, lymphoma would be treated with nonoperative, medical management, whereas gastric adenocarcinoma would require a more extensive gastric resection plus lymphadenectomy. Although resection for a gastric adenocarcinoma may also be performed laparoscopically, the resection involves removing more gastric tissue, and the procedure should be planned appropriately preoperatively.

♦ Some surgeons tattoo the lesion preoperatively, to assist in localization.

Equipment and instrumentation

♦ Standard laparoscopic instruments may be used for gastric wedge resections:

Harmonic scalpel (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) or LigaSure (ValleyLab) for omental dissection, division of short gastric vessels, and adhesiolysis

Harmonic scalpel (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) or LigaSure (ValleyLab) for omental dissection, division of short gastric vessels, and adhesiolysis♦ Intraoperative esophagogastroduodenoscopy may be helpful to localize the lesion, particularly for submucosal lesions, which may not be readily visible laparoscopically.

Anesthesia

♦ Procedures are performed under general anesthesia with muscle relaxant.

♦ Epidural anesthesia is not usually required.

♦ Topical anesthetic agents, such as 0.25% bupivacaine hydrochloride, may be infiltrated at each trocar site.

♦ At induction, intravenous antibiotics (generally a cephalosporin) are administered.

Room setup and patient positioning

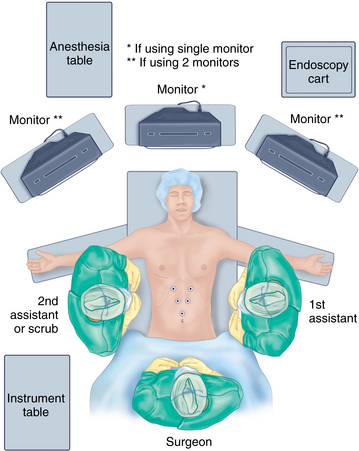

♦ A split-leg table may be helpful, allowing the primary surgeon to stand between the legs. The first assistant surgeon may stand on one side of the patient; a second assistant may stand on the opposite side. The scrub nurse/technician may stand opposite the first assistant or adjacent to either leg (Figure 6-2).

♦ Arms may be tucked or extended on arm boards at the discretion of the surgeon.

♦ If a single video monitor mounted from the ceiling is used, it may be positioned at the head of the table directly over the patient’s head, allowing the surgeon standing between the legs to look directly ahead. If multiple monitors are used, either ceiling mounted or cart based, they may be placed on either side of the patient above the armboards.

♦ An endoscopy cart may be placed near the head of the operating table.

Step 3. Operative steps

Access and port placement

♦ Pneumoperitoneum may be established using an open technique (at the site where the specimen will be extracted) or by insufflation via a Veress needle in the left upper quadrant at the discretion of the surgeon.

♦ Once pneumoperitoneum is established, four or five trocars may be placed in the upper abdomen.

♦ A 12-mm trocar placed supraumbilically midline or just left of midline will accommodate the stapler and specimen bag during the procedure.

♦ A port accommodating the liver retractor may be placed in the right upper quadrant, approximately 45 degrees off of midline and 12 cm to 15 cm from the xiphoid process. For lesions along the greater curvature of the midbody of the stomach well to the left of the lateral edge of the liver, or for instances where the left lateral segment of the liver is small, a liver retractor may not be necessary.

♦ Additional two or three 5-mm ports may be placed in the right and left upper quadrants for the dissecting and grasping instruments. These port sites may be upsized to 10 mm or 12 mm as needed to assist with placement of stapler or specimen bag, depending on the specific location of the tumor on the stomach (Figure 6-2).

Mobilization

♦ The operating room table is repositioned in steep reverse Trendelenburg, allowing omentum and bowel to fall into the lower quadrants and out of the operative field.

♦ The abdomen is surveyed with the laparoscope in the supraumbilical port to identify the primary tumor site, evaluate for evidence of metastatic spread, and select the appropriate sites for the additional ports.

♦ Dissection of the greater and lesser curvatures of the stomach is performed selectively depending on the location of the tumor. The surgeon should avoid directly grasping or manipulating the tumor.

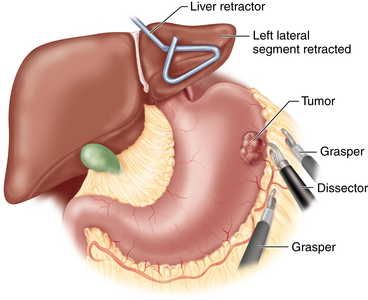

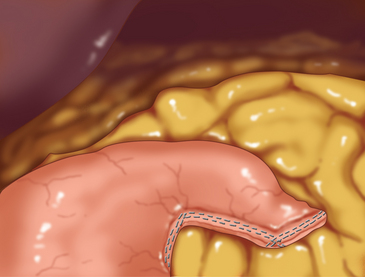

♦ For lesions close to the greater curvature, the omentum is carefully dissected away (the omentum does not necessarily have to be resected with the specimen for nonadenocarcinoma neoplasms). The greater curvature is grasped with a smooth grasper or Babcock clamp and retracted anteriorly (Figure 6-3). Counter traction may be placed directly on the omentum or on the transverse colon. The omentum is dissected off of the stomach using electrocautery, Harmonic scalpel, LigaSure, laparoscopic coagulating shears, or another dissecting instrument. Large branches of the gastroepiploic and short gastric vessels may be secured with clips. The spleen and splenic vessels are preserved.

♦ For lesions close to the lesser curvature, the gastrohepatic ligament is similarly divided. Branches of the right and left gastric vessels are divided between clips. The vagus nerves are preserved unless directly involved with the tumor.

♦ Adhesions in the lesser sac are carefully lysed.

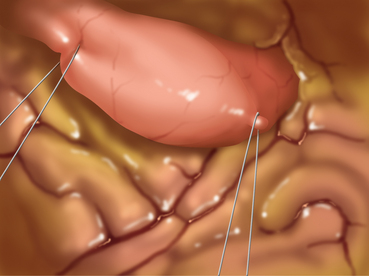

♦ To avoid direct manipulation of the tumor, traction sutures may be placed proximal and distal (or anterior and posterior) to the tumor (Figure 6-4). These sutures may then be grasped for further manipulation rather than grasping the stomach itself.

Division of stomach

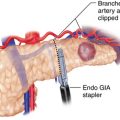

♦ Once the tumor has been sufficiently mobilized, an angulated stapler may be applied. One or more of the 5-mm ports may be upsized to a 12-mm port to accommodate the stapler as needed (Figure 6-5). The stapler should be applied such that the tumor plus a segment of normal surrounding stomach are removed as a wedge. This commonly requires sequential firings of the stapler.

♦ It is critical that a rim of normal stomach, measuring at least 1 cm, around the tumor is removed along with the tumor itself. If there is any concern about the margins of the tumor, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy should be performed to help identify the tumor edges, thereby preventing transection of the tumor. Gastric adenocarcinomas require a wider margin of resection, and thus the wedge resection described in this chapter is not appropriate for this latter diagnosis.

♦ The nasogastric tube should be withdrawn into the esophagus to eliminate the risk of it getting caught in the stapler.

Removal of specimen and completion of procedure

♦ The gastric specimen, once freed, should be placed into a specimen bag.

♦ The gastric staple line should be inspected to rule out bleeding or leakage. Pinpoint sites of bleeding may be carefully cauterized or oversewn. If there is any concern of leakage, an esophagogastroduodenoscopy may be performed after filling the abdomen with saline (and taking the bed out of Trendelenburg position). Insufflation during endoscopy will test the integrity of the staple line. Bubbles from the staple line indicate a leak. The site must be repaired or oversewn. If necessary, the procedure may need to be converted to a laparotomy.

♦ The specimen may be extracted, which may require enlarging the port site. The specimen must be sent to pathology for immediate frozen section analysis to check the adequacy of the margins.

♦ The nasogastric tube should be repositioned in the stomach under visualization prior to removal of the ports.

♦ Larger fascial incisions should be reapproximated with sutures of the surgeon’s choosing.

♦ Subcuticular dissolvable sutures may be used to close the skin incisions.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ Oncologic principles must be maintained for gastric wedge resections performed for neoplasms. Margins of resection in the specimen must be evaluated by intraoperative frozen section analysis. The presence of tumor tissue at any margin of resection on frozen section analysis mandates reexcision at that time to achieve negative margins. The oncologic principles of tumor resection must not be compromised just to avoid a larger resection or conversion to a laparotomy.

♦ Some investigators have suggested that for patients undergoing partial gastric resections for tumors such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors, wedge gastrectomies may only be feasible for tumors localized to the fundus and greater curvature.

♦ Tumors in the antrum may require a laparoscopic distal gastrectomy, and those along the lesser curvature or near the gastroesophageal junction may require a laparoscopic transgastric resection. This is not consistently true. Ultimately, surgeons should determine which approach provides an adequate residual lumen and oncologically appropriate margin.

Kitano S, Shiraishi N. Minimally invasive surgery for gastric tumors. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85(1):151-164.

Ohgami M, Otani Y, Furukawa T, et al. Curative laparoscopic surgery for early gastric cancer: eight years experience. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2000;101;8:539-545.

Otani Y, Ohgami M, Igarashi N, et al. Laparoscopic wedge resection of gastric submucosal tumors. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000;10(1):19-23. xi

Privette A, McCahill L, Borrazzo E, et al. Laparoscopic approaches to resection of suspected gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors based on tumor location. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(2):487-494.