Chapter 15 Gastric Carcinoma

Introduction

Over the past several decades, the incidence of gastric carcinoma in the world has been on a decline. But it remains the second most common cause of cancer-related death worldwide. There are differences in the geographic distribution, epidemiologic trends, presentation, and location of gastric carcinoma that have been studied in detail recently. Gastric carcinoma tends to be diagnosed at an advanced stage, particularly in the West, and generally has a poor prognosis. Japan has the highest incidence of gastric carcinoma, but it also has a national gastric carcinoma screening program, allowing for more patients being diagnosed at an early stage. For localized gastric carcinoma, the best chance for durable disease control and survival is with curative surgery. Unfortunately, surgery alone is not enough when the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate is 23% to 25%.1,2Multimodality therapy has become common practice for resectable gastric carcinoma to improve the rate of disease control and minimize recurrence. Postoperative chemoradiotherapy is the standard of practice in the United States and other parts of North and South America, and perioperative chemotherapy is adopted by most European countries. Regional differences of outcome are probably due to many different factors, most importantly, early disease detection in countries with a screening program, such as Japan, and also difficulty in accurate staging with currently available imaging and staging modalities.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Epidemiology

Although the incidence of gastric carcinoma is decreasing in Western countries, it remains the fourth most frequent cancer diagnosed and the second most lethal cancer worldwide, behind only lung cancer. The number of new cases of gastric carcinoma worldwide was recently estimated as over 600,000 in males and 330,000 in females.3 It is the third most common cancer in males and the fifth most common cancer in females worldwide.4 Sixty percent of cases occur in developing countries.5 The areas with the highest incidence rates are Eastern Asia, South America, and Eastern Europe. Regions in which gastric carcinoma is least frequent are North America, Western Europe, and parts of Africa. There is approximately a 20-fold difference in the incidence rates between Japan and some white populations in the United States.5 In the United States, approximately 21,520 new cases of gastric carcinoma were expected to be diagnosed during 2011, with 10,340 estimated deaths from the disease during the same period.6

Of the several classification systems that have been proposed to describe gastric carcinoma, the Lauren classification is the most widely used. The Lauren classification describes tumors based on the microscopic configuration and growth pattern into intestinal and diffuse types.7,8 Diffuse cancers are noncohesive and diffusely infiltrate the stomach. These often exhibit deep infiltration of the gastric wall and show little or no gland formation. These tumors are often associated with marked desmoplasia and inflammation with relative sparing of the overlying mucosa. The intestinal type, conversely, shows recognizable gland formation similar in microscopic appearance to the colonic mucosa. The glandular formation ranges from well- to poorly differentiated tumors and grows in expanding rather than infiltrative patterns.5 Intestinal cancers are believed to be related to environmental factors and are thought to arise secondary to chronic atrophic gastritis. The diffuse cancers, conversely, are less related to environmental factors and occur more often in young patients.5 The relative incidence of diffuse cancers is believed to have increased mainly owing to the decrease in the incidence of intestinal cancers.9

There are regional differences in the pathology and anatomic location of gastric carcinoma. A predominance of the Lauren intestinal type of adenocarcinoma occurs in high-risk areas, whereas the Lauren diffuse type is relatively more common in low-risk areas. Proximal gastric carcinomas and cancers of the gastroesophageal junction are more common in the West, and distal gastric carcinoma is more common in high-risk regions. At the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 41% of all UGI cancers involve the gastroesophageal junction.10 A steady decline in the incidence and mortality rates of gastric carcinoma has been observed worldwide over the past several decades. This is mainly due to a decrease in the intestinal variety of gastric carcinoma, the incidence of diffuse cancer being relatively stable.5

Etiology and Risk Factors

Because gastric carcinoma is more common in Asian than in Western countries, ethnic origin was thought to be an important contributory factor for the observed difference.11 Although first-generation Asian immigrants to Western countries carry the same high susceptibility for gastric carcinoma as their counterparts in their native country, subsequent generations acquire risk levels approaching that of the population of their adopted countries. This epidemiologic pattern underlines the importance of environmental factors in the pathogenesis of gastric carcinoma.12 Diets poor in fruits and vegetables and rich in smoked or poorly preserved food, salt, nitrates, and nitrites; infection with Helicobacter pylori; and smoking have all been currently implicated as significant risk factors in the development of gastric carcinoma in several studies.13–15 Chronic atrophic gastritis, previous gastric surgery, gastric polyps, and obesity, as well as low socioeconomic status, are also associated with an increased risk of gastric carcinoma.16,17

Gastric carcinoma is also seen as a part of the hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndrome and other gastrointestinal (GI) polyposis syndromes such as Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis.17 Mutations in the E-cadherin gene are a well-recognized cause of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer.18

Clinical Presentation

The symptoms of patients with gastric carcinoma are nonspecific. As a result, diagnosis is often delayed, and patients will have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis. Frequent symptoms associated with gastric carcinoma include dysphagia, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, and other symptoms attributable to gastric outlet obstruction or anemia. However, the most common symptoms at the time of diagnosis are upper abdominal pain and weight loss.19

Anatomy and Pathology

Anatomy

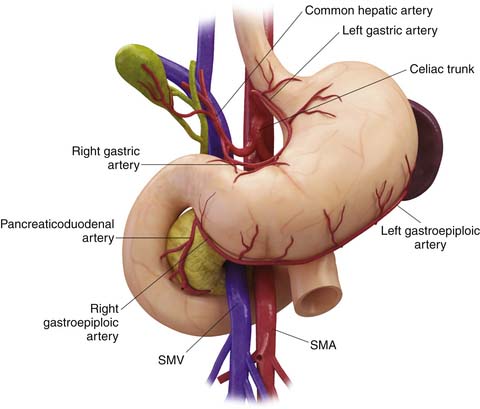

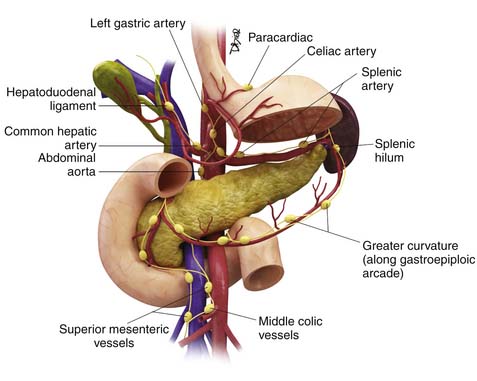

Being a derivative of the foregut, the stomach is almost entirely supplied by the branches of the celiac trunk (Figure 15-1). The left gastric artery, arising from the celiac axis, and the right gastric artery, a branch of the hepatic artery, supply the lesser curvature in the gastrohepatic ligament and form an anastomotic arcade along the lesser curvature. The left and right gastroepiploic arteries, branches of the splenic artery and the gastroduodenal artery, supply the greater curvature of the stomach and traverse the gastrosplenic ligament and the gastrocolic ligament, respectively. The gastrocolic ligament is the supracolic part of the greater omentum. Numerous short gastric arteries, branches of the splenic artery, also supply the greater curvature. A rich lymphatic network accompanies these vessels, creating a conduit for lymphatic drainage, and traverses these complex ligamentous structures. The various ligamentous attachments can be identified by noting vascular landmarks on cross-sectional imaging (Table 15-1).20 These ligamentous structures are important to understand because they represent the critical conduits for local extension of primary gastric carcinoma.

Table 15-1 The Various Ligamentous Attachments of the Stomach Can Be Identified by Identifying Vascular Landmarks on Cross-Sectional Imaging

| PERITONEAL LIGAMENTS AND FOLD | RELATION TO ORGANS | VASCULAR LANDMARK |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrohepatic ligament | Lesser curvature of the stomach to the liver | Left and right gastric arteries |

| Hepatoduodenal ligament | From the duodenum to the hepatic fissure | Proper hepatic artery, portal vein |

| Gastrocolic ligament | Greater curvature of the stomach to the transverse colon | Left and right gastroepiploic arteries and vein |

| Gastrosplenic ligament | From the left side of the greater curvature of the stomach to the splenic hilum | Left gastroepiploic vessels |

From Vikram R, et al. Pancreas: peritoneal reflections, ligamentous connections, and pathways of disease spread. Radiographics. 2009;29:e34.

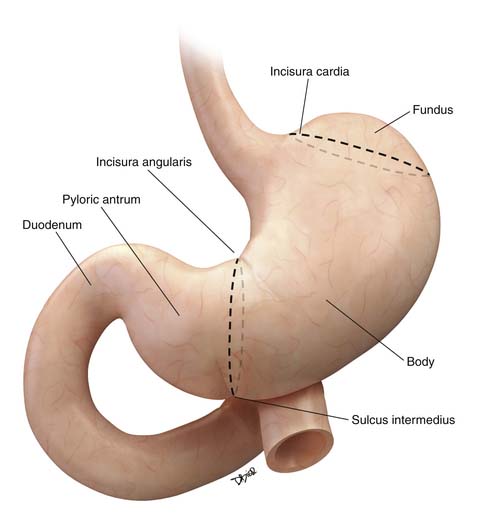

The stomach is divided for descriptive purposes into the fundus, body, pyloric antrum, and pylorus by imaginary lines drawn on its external surface (Figure 15-2). The fundus is dome-shaped, immediately under the left dome of the diaphragm, and is superior to the cardiac orifice. It lies above an imaginary line drawn horizontally at the level of the cardia (incisura cardia) to the greater curvature. At the lower end of the lesser curvature is a constant external notch (incisura angularis). The body extends from the cardia to the incisura angularis. A slight groove, the sulcus intermedius on the greater curvature of the stomach, separates the body from the pyloric antrum. The antrum extends from an imaginary line drawn from the incisura angularis to the sulcus intermedius. The pylorus is the narrowest part of the stomach, measuring only about 1 to 2 cm in length, and terminates into the duodenum (see Figure 15-2).21

Key Points Anatomy

• The stomach is divided into the fundus, body, pyloric antrum, and pylorus by imaginary lines drawn on its external surface.

• The stomach is almost entirely supplied by the branches of the celiac artery.

• Complex ligamentous attachments of the stomach provide conduits for direct spread of malignancies to the adjoining structures and the peritoneum.

Pathology

Malignant tumors of the stomach can be divided into four major subtypes based on cells of origin: epithelial, mesenchymal, and neuroendocrine tumors, and lymphoma. Leiomyosarcomas, neurofibrosarcomas, and malignant GI stromal tumors are mesenchymal in origin. The WHO classification of gastric tumors takes into consideration the morphologic and molecular characteristics of the tumors and is shown in Table 15-2.5

Table 15-2 The World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Stomach

| EPITHELIAL TUMORS | NONEPITHELIAL TUMORS |

|---|---|

| Intraepithelial neoplasia—adenoma | Leiomyoma |

| Carcinoma | Schwannoma |

| Adenocarcinoma | Granular cell tumor |

| Papillary adenocarcinoma | Glomus tumor |

| Tubular adenocarcinoma | Leiomyosarcoma |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | Gastrointestinal stromal tumor |

| Signet-ring cell carcinoma | Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | |

| Small cell carcinoma | |

| Undifferentiated carcinoma | |

| Carcinoid (well-differentiated endocrine neoplasm) |

Modified from Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2000.

Malignant epithelial tumors constitute the majority of gastric neoplasias, and nearly 90% of them are adenocarcinomas. Several classification systems are used for describing adenocarcinomas. Based on histology, they are subdivided into tubular, papillary, mucinous, and signet-ring cell carcinomas.5 Usually, one of the subtypes predominates in adenocarcinomas. Based on gross appearance, it is classified into four types. Type I is a polypoid and fungating variety; type II is a polypoid tumor with central ulceration; type III is an ulcerated tumor with infiltrative margins; and type IV is linitis plastica.8,22 This method of classification is called the Borrmann classification and is generally reserved for advanced cancers. However, the simplest and the most widely accepted classification is the Lauren classification in which the gastric carcinomas are divided into two types: intestinal and diffuse.7,8 The intestinal type is associated with various degrees of glandular formation and intestinal metaplasia. The diffuse type is infiltrative and presents as a plaque or linitis plastica and tends to be poorly differentiated or of a signet-ring variety.5 Those cancers having features of both intestinal and diffuse types are considered mixed.

Key Points Pathology

• Ninety percent of malignant epithelial tumors of the stomach are adenocarcinomas.

• Several histologic classification systems are used, but the simplest and most widely accepted is the Lauren classification in which gastric carcinomas are divided into two types: intestinal and diffuse.

• Intestinal cancers show an expansile growth pattern with recognizable gland formation similar in microscopic appearance to the colonic mucosa. Diffuse cancers are noncohesive, diffusely infiltrate the gastric wall, and are associated with desmoplasia and inflammation.

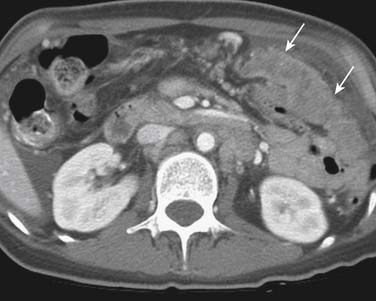

Patterns of Tumor Spread

Gastric carcinoma shows a propensity to spread through direct contiguous invasion of adjacent peritoneal reflections and also to adjacent organs. In addition, dissemination via lymphatic and hematogenous routes also occurs. Both Lauren intestinal and diffuse varieties show a propensity for direct contiguous spread, but it is more commonly seen in the diffuse type of cancer. The gastrocolic, gastrohepatic, gastrosplenic, and hepatoduodenal ligaments all serve as conduits for tumor dissemination. Once the integrity of the peritoneal lining is breached, the tumor can seed into the peritoneal cavity, likely in the greater omentum, the paracolic gutters, and the pelvic floor. It is not uncommon to encounter tumor deposits in the ovaries and the rectovesicle pouch.

Periserosal implants into adjacent and distant organs are not infrequent, particularly with diffuse cancers, producing an appearance similar to linitis plastica, commonly in the colon.23,24

Lymphatic spread is seen commonly in advanced and not infrequently in early gastric carcinomas. Several nodal stations drain the stomach. These generally run parallel to the gastric blood supply: lymphatics along the lesser curve drain to the left gastric and celiac nodes; lymphatics along the pylorus and lesser curvature run parallel to the right gastric artery and drain into the hepatic and celiac nodes; a third group of lymphatics drain the proximal greater curvature of the stomach into the pancreaticosplenic nodes; and the fourth group parallels the right gastroepiploic vessels along the greater curvature and drain into the infrapyloric nodes and the nodes in the transverse mesocolon (Figure 15-3).

Figure 15-3 The major nodal stations draining the stomach. These generally parallel the gastric blood supply.

Key Points Pattern of tumor spread

• Direct contiguous spread occurs via the various ligamentous connections of the stomach such as the gastrocolic, gastrohepatic ligament, gastrosplenic, and hepatoduodenal ligaments.

• Peritoneal dissemination and seeding are common in advanced gastric carcinoma. Transperitoneal seeding of tumor to other abdominal organs is also seen.

• Lymphatic spread is to the perigastric and regional lymph nodes running parallel to the branches of the celiac artery.

• Hematogenous spread occurs to the liver, lungs, bones, and other soft tissues.

Staging

The tumor, node, and metastasis (TNM) staging is the most widely accepted method for staging gastric carcinomas.25 Radiologic investigations such as CT, MRI, and ultrasound (US) are used for preoperative staging. Pathologic staging is considered the gold standard, particularly in specimens not subject to preoperative chemo- or radiotherapy (Tables 15-3 and 15-4).

Table 15-3 The American Joint Committee on Cancer Tumor-Node-Metastasis Classification

| Primary Tumor (T) |

| TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0: No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis: Carcinoma in situ: intraepithelial tumor without invasion of the lamina propria |

| T1: Tumor invades the lamina propria or submucosa |

| T2: Tumor invades the muscularis propria or the subserosa |

| T2a: Tumor invades the muscularis propria |

| T2b: Tumor invades the subserosa |

| T3: Tumor penetrates the serosa (visceral peritoneum) without invading adjacent structures |

| T4: Tumor invades adjacent structures |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) |

| NX: Regional lymph node(s) cannot be assessed |

| N0: No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1: Metastasis in 1 to 6 regional lymph nodes |

| N2: Metastasis in 7 to 15 regional lymph nodes |

| N3: Metastasis in more than 15 regional lymph nodes |

| Distant Metastasis (M) |

| MX: Distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

| M0: No distant metastasis |

| M1: Distant metastasis |

From Stomach. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York: Springer; 2010:145-152.

Depth of invasion or T stage is an important independent prognostic factor for both survival and local recurrence. T1 cancers have a 10-year survival rate of approximately 80%, T2 lesions have a 10-year survival rate of 55%, and T3 and T4 lesions, only 30%.26–29

Knowledge of nodal anatomy is very important in staging lymph nodes in gastric carcinoma, because this is useful in surgical planning. The Japanese Research Society for Gastric Carcinoma has classified the regional lymph nodes based on location.30 These are further classified as compartments 1 to 4. Compartment 1 consists of the perigastric lymph nodes. Compartment 2 includes lymph nodes along the left gastric artery, common hepatic artery, celiac axis, and splenic artery. Compartment 3 includes lymph nodes along the hepatoduodenal ligament, at the posterior head of the pancreas, and at the root of the mesentery. In cancers of the antrum, the lymph nodes along the splenic artery are classified as compartment III. Para-aortic lymph nodes constitute compartment 4. These are useful in describing the extent of lymph node dissection in surgery. D1 dissection includes compartment 1; D2, compartments 1 and 2; D3 dissection compartments 1, 2, and 3; and D4 dissection includes all four compartments.

Although compartmental dissection is methodologically sound, the International Committee on Gastric Carcinoma has recommended that, for accurate staging and predicting prognosis, a minimum of 16 lymph nodes has to be included in the surgical specimen before an N stage can be determined.31 N stage is an independent variable for survival: N0 disease has a 10-year survival rate of 70%; N1, 41%; and N2 or N3, less than 20%.32

Key Points Staging

• TNM system is the most commonly used system and is an important prognostic factor.

• Nodal stations are classified into different compartments based on the distance from the primary tumor. These compartments are used to guide surgery.

• At least 16 nodes should be harvested at surgery and pathologically evaluated to complete pathologic staging for gastric carcinoma.

Imaging Evaluation

Tumor Detection and Staging

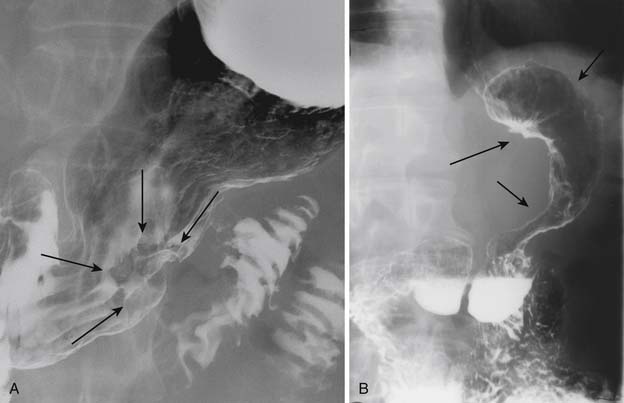

EGD has replaced UGI double-contrast barium study as the modality of choice to detect and diagnose gastric carcinoma owing to its specificity and the advantage of obtaining a tissue biopsy and also the ability to perform EUS, which offers a reliable way to T-stage the tumor.33 However, some reports indicate that endoscopy and UGI barium studies are equally sensitive in detection of primary gastric carcinoma.34,35 Gastric carcinoma has various appearances on GI barium studies. These include plaquelike lesions, sessile or pedunculated polypoid lesions, ulcerated lesions, and nondistention of the stomach as in the scirrhous type of carcinoma or linitis plastica with diffuse loss of mucosal detail (Figure 15-4).

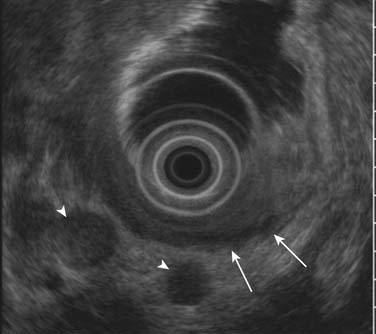

EUS is superior to all other modalities in visualizing the different layers of the gastric wall and, thus, is most accurate in preoperative local (T) staging of gastric tumors with a accuracy rate of 78% to 94%.36,37 Despite this, it is not uncommon (particularly for T2 tumors) that there is discordance with the actual pathologic specimen. The gastric wall layers appear as a five-layered structure on EUS with alternating hyperechoic and hypoechoic bands: serosa, muscularis propria, submucosa, deep mucosa, and superficial mucosa.38 Tumors generally are hypoechoic or hyperechoic and are seen disrupting this regular pattern. EUS is also valuable in assessing smaller perigastric lymph nodes (Figure 15-5). EUS is of little to no benefit after preoperative therapy.

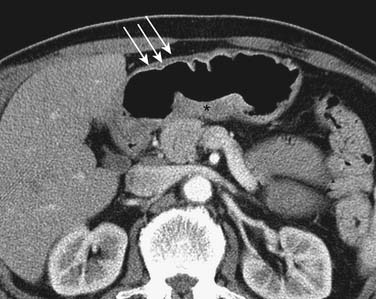

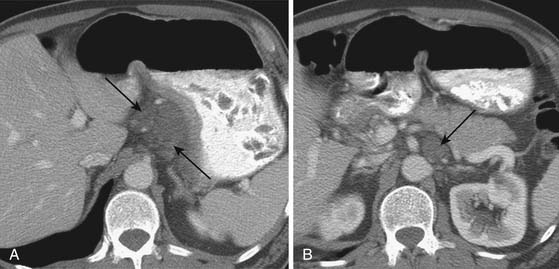

CT is generally less accurate than EUS for T staging of gastric tumors. However, with the latest development in multidetector scanners, optimization of gastric distention, negative oral contrast, and dynamic contrast-enhanced CT with multiplanar reconstructions, the accuracy of CT in T staging appears to have improved.39 The normal gastric wall shows a two- to three-layered structure: an inner, markedly enhancing mucosal layer; a submucosal layer with low attenuation; and an outer muscular-serosal layer with moderate enhancement (Figure 15-6).40 T staging is assessed by studying the integrity of these layers. On CT, T1 and T2 lesions are limited to the gastric wall. T3 lesions, however, may show slight blurring of the serosal contour with associated stranding of perigastric fat.41 T4 lesions spread via ligamentous attachments and peritoneal reflections in T4 lesions (Figures 15-7 and 15-8). The early phase of the multiphase dynamic CT study after intravenous contrast is considered optimal in determining the depth of tumor invasion as well as defining the vascular anatomy of the stomach.42 Takao and coworkers,43 in a study on 108 patients with gastric carcinoma using a multiphasic protocol CT, report a tumor detection rate and T staging accuracy of 98% and 82% for advanced gastric carcinomas. However, the detection and accuracy of T staging in early gastric carcinomas was significantly low at 23% and 15%, respectively. Use of multiplanar re-formatting (MPR) in coronal and sagittal planes appears to improve detection and T staging.39,44 To improve the quality of three-dimensional (3D) imaging, however, thinner slices of at least 1.25-mm slice thickness are required. Advanced postprocessing techniques with volume rendering to produce an endoscopic-type image (virtual gastroscopy) have also been described.45

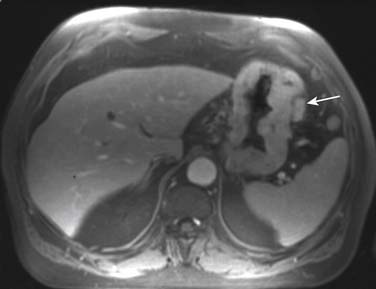

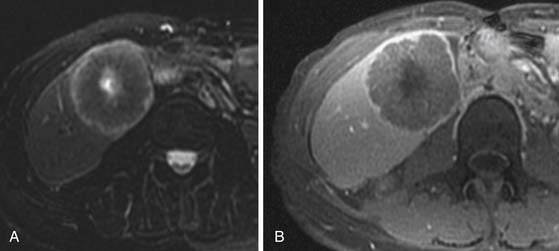

The major advantage of MRI is multiplanar capability and better tissue contrast. However, the use of MRI in staging gastric carcinoma is limited owing to respiratory and cardiac motion, although some smaller studies report that MRI is comparable with CT for T staging.46 Fat-suppressed 3D T1-weighted postcontrast acquisitions can demonstrate the mucosal lesion in the arterial phase. Loss of rugae and diffuse thickening and enhancement of the gastric mucosa and wall represent diffuse scirrhous tumors or linitis plastica (Figure 15-9).

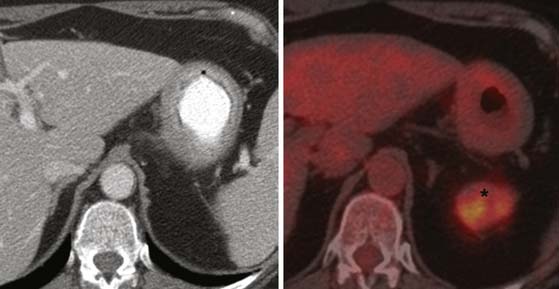

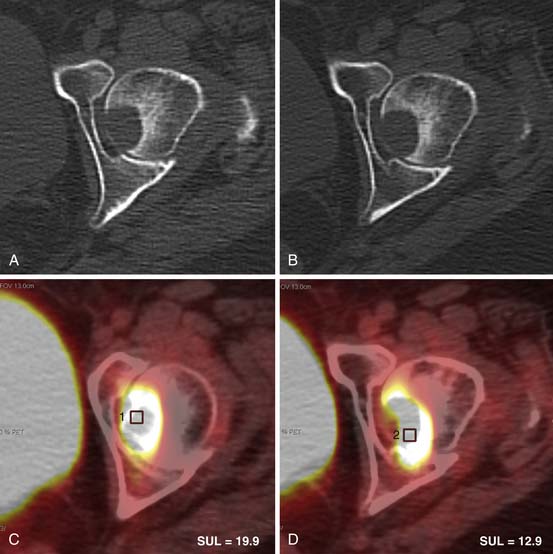

Fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG)-PET and PET/CT perform inconsistently in detection of gastric carcinoma and are not useful in the T staging of gastric carcinomas because of the normal background uptake of FDG in the gastric mucosa and also the variability in FDG uptake depending on the tumor’s histologic type. Signet-ring carcinoma (diffuse type) and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma show little to no uptake (Figure 15-10).47,48 The use of water to distend the stomach appears to improve the specificity of PET/CT for diagnosis to a modest degree.49 However, owing to its poor performance, the role of PET/CT in diagnosis and T staging of gastric carcinoma is uncertain.

Lymph Node Staging

Nodal staging is challenging even with the current advances in imaging technology owing to significant limitation in detecting microscopic metastases by currently available imaging modalities. Owing to the lack of any reliable indicator to detect metastatic lymph nodes on cross-sectional imaging, size is the major criterion used, with a presumed upper limit of 8 to 10 mm in short-axis diameter(Figure 15-11; see also Figure 15-9).This parameter has significant shortcomings. In a prospective study in patients with gastric carcinoma, Monig and colleagues reported that 80% of lymph nodes less than 5 mm in size were benign but 55% of metastatic lymph nodes were also less than 5 mm in diameter, clearly demonstrating the weakness of any size criterion as a parameter on imaging modalities.46,50

In addition to the challenges faced by CT regarding the staging of lymph nodes, MRI also suffers owing to movement artifact due to peristalsis and breathing.51 Hence, CT is marginally better in staging lymph nodes (73% vs. 65%).46,52 Use of lymphotrophic ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide (USPIO) particles—ferumoxtran-10—for detecting metastatic lymph nodes showed some promise in staging distant lymph nodes such as those in the retroperitoneal and para-aortic regions. Owing to movement artifact, the nodes in the perigastric region are not clearly assessed. Tatsumi and associates53 demonstrated a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 92.6% in detecting metastatic lymph nodes using lymphotrophic USPIO particles in MRI. Currently, the USPIO is not commercially available in the United States, which limits its clinical application.

FDG-avid nodes on PET/CT are likely malignant, and hence, PET/CT enjoys a higher specificity than CT or MRI. However, PET/CT suffers from inherently poor resolution and, hence, poor sensitivity.54 In addition, the previously mentioned lack of FDG avidity for diffuse type cancers is a severe limitation (see Figure 15-10). Therefore, the likelihood of this modality improving nodal staging is remote unless there is technologic innovation with widespread availability of high-resolution PET/CT scanners.

Metastatic Gastric Carcinoma

Involvement of distant lymph nodes such as the right supraclavicular lymph node (Virchow node) is considered distant metastasis, and curative surgery is not feasible in such patients (Figure 15-12). According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging, the presence of cancer in hepatoduodenal, retropancreatic, mesenteric, and para-aortic, is classified as distant metastasis.25

CT scan of the chest is considered essential in patients to stage gastric carcinoma and to look for pulmonary metastases. Even though postmortem studies have put the incidence of pulmonary metastasis in gastric carcinoma as high as 25%, such a picture is not commonly seen in the clinical setting.40

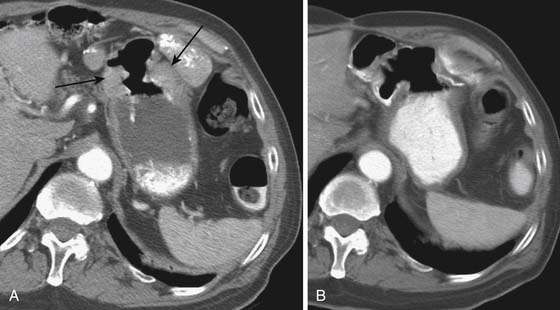

Advanced gastric carcinoma metastasizes much more frequently into the peritoneum, typically to the omentum (Figure 15-13), ovaries (Krukenberg’s tumor, usually bilateral) (Figure 15-14), or rectovesicular pouch (Blumer’s shelf tumor).40 Ascites in gastric carcinoma was shown in one study to be associated with positive free tumor cells (40% sensitivity and 97% specificity) and peritoneal metastasis (51% sensitivity and 97% specificity).55

Although laparoscopy predates CT in staging peritoneal disease, it remains superior to all other imaging modalities in small-volume peritoneal disease. Its sensitivity for detecting peritoneal disease is quoted as 96%.56 Various factors are likely to affect the ability of CT to detect peritoneal metastasis, including size, location, and morphology of the deposits and the presence or paucity of intra-abdominal fat.11,57 On CT, peritoneal metastasis can be seen as a nodular mass, peritoneal plaque, or infiltrative soft tissue mass lesion.41 A diffusely thickened and enhancing peritoneal lining can be a manifestation of diffuse peritoneal carcinomatosis.

MRI is considered superior to CT scan by some authors in detecting extra-gastric metastasis.51,58 Owing to factors such as greater soft tissue resolution and greater sensitivity to contrast enhancement, and the recent development of hepatobiliary contrast agents, MRI can be superior to CT in detecting hepatic metastases (Figure 15-15).58 Its multiplanar capabilities make it useful in detecting peritoneal metastasis, but laparoscopic staging has been proved to be superior to both CT and MRI in detecting peritoneal involvement.

The value of PET/CT is limited by the poor FDG avidity of some subtypes, notably the signet-ring cell variety. However, in some instances, it may be useful in detecting distant metastasis that may not be seen on conventional imaging. In fact, there are a few authors reporting that use of PET/CT changed management by detecting unsuspected metastasis.59,60 However, there are currently no data to support the widespread use of PET/CT in routine use.

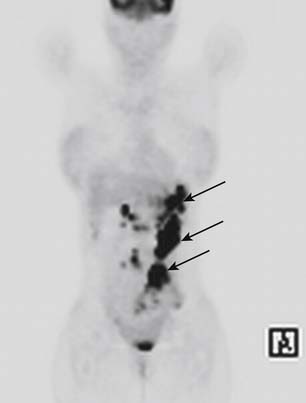

PET may be useful in detecting peritoneal metastases in some instances. Some studies have shown that PET has a greater sensitivity than CT in detecting peritoneal metastasis.61,62 There are two distinct patterns described in peritoneal metastasis in PET.41 One is a diffuse increase in uptake in which the silhouette of the abdominal organs such as the liver and spleen is obscured, indicating diffuse peritoneal carcinomatosis. The second is nodular increase in uptake in areas not corresponding to the normal anatomic locations of nodes or other solid organs (Figure 15-16). The detectability of metastasis has benefited considerably from combined PET/CT because of its ability to distinguish abnormal uptake from bowel activity.62 It should be remembered, however, that certain histologic types of gastric tumors such as signet-cell carcinoma and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (the most common type of gastric carcinoma to spread to the peritoneum) have little to no FDG uptake, and therefore, their metastatic deposits may not be picked up on PET.47

Figure 15-16 Coronal PET scan of a patient with gastric carcinoma with multiple nodular FDG-avid peritoneal deposits (arrows).

Treatment

The treatment modality of gastric carcinoma offering the best chance of cure is complete surgical resection (R0). Unfortunately, because most patients will present with advance gastric carcinoma and because of inaccuracy of clinical staging, the 5-year survival rate with surgery alone is approximately 25%.1,2 In individuals with a high risk of recurrence, locoregional control with concurrent chemoradiotherapy and perioperative chemotherapy is the current standard of care in Western countries.

Surgery

The surgeons dealing with gastric carcinoma will have to make a series of choices in designing the most appropriate surgery for a particular patient by taking into consideration the location of the cancer (proximal versus distal), type of cancer (intestinal versus diffuse), stage of the cancer, reconstruction options, and lastly, patient factors such as overall fitness and risk of surgery.63

For early gastric carcinoma, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or limited resections may be used. EMR is a technique developed and popularized for use in select patients with early gastric carcinoma. These cancers are generally T1a tumors less than 2 cm, either flat or protuberant, and have no ulceration or involvement of the submucosa.64,65 In the United States, because early gastric carcinoma is not common, expertise with EMR is limited.

Resection of small T1b tumors with only a cuff of surrounding stomach tissue with limited dissection of lymph nodes is occasionally performed. However, there are no data that directly compare these techniques to the more conventional surgery. However, the outstanding survival results (approaching 100%) for properly selected patients for EMR attest to its appropriate use. Laparoscopic gastrectomy or laparoscopic-assisted gastrectomy is also practiced in some centers with improved postoperative morbidity.66 However, there are no data to compare the long-term survival in these patients, and some series describe a slightly higher incidence of positive margins of resection.63,67

Aggressive gastric surgery has been practiced for many decades in the East and is followed by many surgeons who see large numbers of gastric carcinoma patients in the West. This includes an extended lymph node dissection along with appropriate luminal resection. The extent of lymphadenectomy is a subject of considerable debate.63,68 D1 lymphadenectomy and D2 lymphadenectomy are commonly followed. A meta-analysis of several trials found no significant difference in the mean 5-year survival of patients who underwent gastrectomy with D1 and D2 dissection (mean weighted 5-yr survival of 41% and 42.6%, respectively).69 However, with the T3 and T4 lesions, patients with a D2 lymphadenectomy had a slightly better outcome but this was not statistically significant. In two large prospective, randomized trials of D2 versus D1 dissection in Western patients, D2 lymphadenectomy clearly resulted in a significant increase in mortality. But a subgroup analysis showed that there was a very strong and independent association between postoperative mortality and splenectomy.69 These studies have substantial issues that limit the applicability of their conclusions. At high-volume centers here and elsewhere, D2 dissection is routinely performed with mortality rates that are lower than that for the D1 dissection in the randomized trials. In the authors’ institute, spleen-sparing D2 lymphadenectomy is routinely performed, with an operative mortality rate of 2% or less (in patients who are usually receiving neoadjuvant therapy).19

More radical dissections with D3 and D4 lymphadenectomy that include para-aortic nodes are less commonly performed even in Asian countries, particularly after the publication of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) 95-01 randomized trial, which demonstrated no benefit and increased morbidity.68,70

Surgery is also sometimes used for palliation of intractable symptoms not responding to conservative management. The symptoms of advanced gastric carcinoma include pain, vomiting, GI bleeding, and anorexia. Although anorexia is not relieved by palliative surgery, intractable nausea and vomiting due to gastric obstruction may be helped by either inserting a duodenal stent or gastric bypass surgery.71 These procedures, however, are fraught with potential problems and should be considered only in extenuating circumstances. However, the use of palliative surgery for gastric carcinoma has decreased over the past few decades with development and improvement of the nonsurgical techniques as well as recognition of the severely limited prognosis for patients with stage IV disease and this degree of symptoms.

Key Points Role of surgery

• Primary curative treatment of gastric carcinoma is complete curative resection.

• Early gastric carcinoma: limited procedures such as EMR and limited local excision of cancer may be used in appropriately selected cases.

• Gastrectomy with lymph node dissection is commonly performed; the extent of lympadenectomy is a subject of ongoing debate

• D1 dissection includes perigastric nodes; D2, perigastric plus along the hepatic, splenic, left gastric, and celiac arteries; D3, dissection as the other forms plus para-aortic nodes.

• Surgery is also sometimes used for palliation of intractable symptoms not responding to conservative management.

Chemotherapy and Radiation Therapy

Traditionally, the universally accepted standard treatment for patients with potentially resectable disease was surgery alone. In those patients, in whom curative surgery is not possible, the treatment is often time-limited to chemotherapy with or without definitive chemoradiotherapy. The use of chemoradiotherapy is extrapolated from results of earlier unresectable localized esophageal cancer studies, most notably the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) 85-01 trial in which the relapse-free survival and OS rates were improved with concurrent chemoradiotherapy.72The Intergroup 123 trial, in which patients with localized but unresectable esophageal cancer were treated with either standard-dose (50.4 Gy) radiotherapy or higher-dose (64.8 Gy) radiotherapy while concurrently on a chemotherapy regimen of weekly cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) once every other week, suggested some surprising results, indicating that combining standard-dose radiotherapy with chemotherapy results in similar survival outcomes without adding significant toxicity. Currently, many physicians consider concurrent chemoradiotherapy as standard therapy where possible.

Although surgery remains the modality with the best chance for durable survival, the survival figures, particularly in the Western countries, are not satisfactory. Hence, many clinical trials to assess the additional survival advantage of adjuvant multimodality therapy in patients with localized resectable disease have been performed. Many of the older studies were inadequately designed to answer this question, and their results were inconsistent. Results from more recent clinical trials during the 2000s have firmly established that adjuvant therapy to surgery improves survival outcomes. Another confounding factor that has not been completely resolved regards to the timing of adjuvant therapy (pre-, post-, or perioperative). Results from many clinical studies had shown variable results regarding the benefit of postoperative chemotherapy. Results of several meta-analyses are available that suggest a benefit with postoperative chemotherapy. However, subgroup analysis demonstrates that the benefit is restricted to patients in Asian countries. Whereas postoperative chemotherapy with S1 is the standard of care for Japanese and Asian patients with resectable gastric carcinoma, management of resectable gastric carcinoma in Western countries is predominantly guided by two positive randomized phase III studies.1,2,73–76

In the United States, the Intergroup 116 conducted a phase III randomized adjuvant therapy.77 Gastric carcinoma patients after R0 resection were then randomized to receive either observation or postoperative therapy. Postoperative therapy consisted of one cycle of chemotherapy with bolus 5-FU and leucovorin, followed by 4 to 5 weeks of concurrent chemoradiotherapy, then two more cycles of chemotherapy. Macdonald and coworkers,1 reported their results in the 2001 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, showing that postoperative chemotherapy plus chemoradiotherapy improved the 3-year survival rates from 41% to 50%. Although applauded for being the first adjuvant trial that completed as well as demonstrated statistically significant results, Intergroup 116 was also criticized on several points. First, only approximately 10% of patients had D2 and 50% had D1 lymph node dissection.75 Most would argue that the additional therapy after surgery may not have been necessary if patients had optimal resection. Second, it was found that many patients’ radiotherapy fields had to be revised when their treatment plans were centrally reviewed, prompting some critics to suggest that community practice is not the best place to practice multimodality therapy. Third, only those patients who did well after surgery were enrolled and randomized onto the study, introducing a selection bias and arguably limited applicability of results to other subgroups of patients. It is also important to note that only 64% of the patients completed the full postoperative course, highlighting the difficulty in patient compliance with multimodality, intense, postoperative therapy. Overall, despite all its criticisms, the results of the Intergroup 116 established that additional postoperative therapy with chemotherapy-chemoradiotherapy improves survival outcome after surgery.

The MAGIC (The Medical Research Council Adjuvant Gastric Infusional Chemotherapy) trial, reported by Cunningham and colleagues,2 with perioperative chemotherapy showed an improvement in survival with addition of perioperative chemotherapy using epirubicin, cisplatin plus infusional 5-FU (ECF); three cycles were given before and after surgery. Patients on the perioperative chemotherapy arm compared with those on surgery alone arm had better median OS (30 mo vs. 18 mo) and more were able to have curative surgery (74% vs. 68%).2 These results offer another option into the management of patients with resectable gastric carcinoma. Unfortunately, because there is no head-to-head comparison between the American postoperative chemoradiotherapy and the U.K. perioperative chemotherapy, it is not clear which option is superior. Several observations can be made when the results of Intergroup 116 and MAGIC are combined. It is clear that surgery alone for patients with locally advanced gastric carcinoma is not adequate. Survival can be improved with additive therapy; possibly similar with either approach. Therapy given preoperatively potentially can downstage and improve the surgical cure rate. Therapy given postoperatively is associated with less tolerance and compliance, with more patients unable to finish therapy. In order for the patients to get the maximum amount of effective therapy, it is apparent that therapy has to be given before surgery. It may not be as important to know which one is better as to be able to have options for patients before going into their curative surgery.

Advanced or Metastatic Gastric Carcinoma

Patients with advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric carcinoma may benefit from systemic chemotherapy to palliate symptoms and possibly improve survival outcome.78,79 Patient selection is important, and those with intact performance status tend to have a more meaningful benefit with chemotherapy.

The chemotherapy regimens used are variable and are regionally dependent. Cisplatin plus 5-FU (CF) and ECF were the standard regimens used in the United States and Europe. More recently, docitoxen in combination with CF has been found to be superior. Use of capecitabine or oxaliplatin in combination with cisplatin or 5-FU have been found to be of comparative efficacy.80–83

In the interest of improving efficacy without adding toxicity, recent studies have focused on the use of bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody against vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Use of bevacizumab in combination with cisplatin and irinotecan has been shown to improve time to progression compared with historical control (8.4 mo vs. 5.8 mo).84 Results from a more recent international phase III randomized study, AVAGAST (Avastin in Gastric Cancer) performed on 774 therapy-naïve patients with advanced or metastatic gastric carcinoma randomized to receive capecitabine plus cisplatin (XP) or infusional 5-FU plus cisplatin (FP) with or without bevacizumab, are available. The data, presented during ASCO 2010, show that progression-free survival (PFS) is better with bevacizumab but OS is not different with the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy.85 However, subgroup analysis suggested that OS did favor the bevacizumab plus chemotherapy arm among patients from the West. The role of bevacizumab remained open, because more studies are ongoing. Investigations are under way to evaluate other monoclonal antibodies such as cetuximab and panitumumab in order to address the role of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) therapy in gastric carcinoma.86,87

Perhaps the most exciting and practice changing study in the past 18 months is the ToGA (Trastuzumb for Gastric Cancer) study.88 HER2 amplification and overexpression occur in approximately 20% to 30% of patients with gastric carcinomas and are associated with poorer survival. In fact, HER2 amplification occurs more frequently in Laurent’s intestinal than in diffuse-type gastric carcinoma.89 Among 3807 patients screened, only 810 were HER2-positive, and out of those, 584 had advanced or metastatic disease, eligible to enroll in ToGA. Patients were randomized to receive FP/XP with or without trastuzumab. The benefit of trastuzumab was true in all measure of outcomes. Overall response rate (ORR) (47% vs. 35%, P = .0017), median PFS (6.7 mo vs. 5.5 mo; hazard ratio [HR] 0.71; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.59-0.85, P = .0002), and OS (13.8 mo vs. 11.1 mo, HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.60-0.91, P = .0046) durations all favor trastuzumab plus chemotherapy. The strongest benefit occurred in patients with HER2 expression that are immunohistochemical (IMHC) grade 3+ or IMHC grade 2+ with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) positive. For the first-time patients, gastric carcinoma has a molecular predictor of response that can be easily evaluated. The role of anti-HER2 therapy is still being studied, but it had been suggested to bring trastuzumab into adjuvant therapy for patients with resectable disease.

Surveillance and Recurrence

Ikeda and associates90 found that nearly 42% of patients with gastric carcinoma who undergo curative surgical resection face disease recurrence and that most of these recurrences are identified within the first 2 years. The cancer recurs locally in 54%, at a distant metastatic site in 51%, and in the peritoneum in 29%. Lymph node metastasis and old age were found to be risk factors for recurrence. There are no reliable tumor markers that can be used to detect recurrence early.

Follow-up after curative resection is performed generally to detect recurrent disease early with the hope that this will lead to improved outcomes. There is a lack of recommendations or national protocols in follow-up of these patients owing to the paucity of high-quality evidence. Hence, many surgical centers have adopted widely disparate regimes with the only constant being visits to the outpatient department. Recurrent disease is rarely curable, and therefore, some argue that there is no benefit from follow-up.91,92

CT scan is standard modality used in most centers performing screening to look for recurrence and is typically performed biannually for 5 years. Distinguishing postsurgical and postradiotherapy changes from tumor recurrence remains a problem in CT. Improperly distended bowel, surgical placation, postoperative adhesions, or hypertrophic gastritis at the stoma can all be mistaken for local recurrence (Figure 15-17).93 PET can sometimes help in differentiating posttreatment changes from recurrence when CT findings are equivocal.

Most centers perform routine endoscopy to diagnose anastomotic recurrence. MRI can be slightly superior to CT in detecting liver metastases owing to its superior contrast resolution. However, the most specific test in diagnosing metastases is FDG-PET/CT (>85% specificity, 90% sensitivity), followed by MRI (76%) and CT (72%).94 It is likely that use of PET/CT may increase in these patients in the near future owing to its increased specificity.

Key Points Surveillance and recurrence

• Nearly 42% of patients with gastric carcinoma who undergo curative surgical resection face disease recurrence and most of these recurrences are identified within the first 2 years.

• Cancer recurs locally in 54%, at a distant metastatic site in 51%, and in the peritoneum in 29%.

• There are no reliable tumor markers that can be used to detect recurrence early.

• CT scan is the modality of choice in detecting for recurrence.

1. Macdonald J.S., et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725-730.

2. Cunningham D., et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11-20.

3. Ferlay J., Bray F., Pisani P., et al. GLOBOCAN 2002: Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide, Version 2.0. IARC CancerBase. 2004:5.

4. Ferlay J., et al. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2006. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:581-592.

5. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the digestive system. In: Hamilton S., Aaltonen L. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon, France: IARC Press, 2000.

6. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2011. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2011.

7. Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. an attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:1-49.

8. Kuan S.-F. Pathology of gastric neoplasms. In: Posner M.C., Vokes E.E., Weichselbaum R.R. Cancer of the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract. Hamilton, Ontario, and London: BC Decker Inc, 2002. :218-236

9. Dicken .J., et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma: review and considerations for future directions. Ann Surg. 2005;241:27-39.

10. Ajani J.A., Curley S.A., Janjan N.A., Lynch P.M.. Gastrointestinal Cancer. New York: Springer; 2005. MD Anderson Cancer Care Series

11. Davis P.A., Sano T. The difference in gastric cancer between Japan, USA and Europe: what are the facts? what are the suggestions? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;40:77-94.

12. Gore R.M., et al. Gastric cancer. Radiologic diagnosis. Radiol Clin North Am.. 1997;35:311-329.

13. Huang X.E., et al. Effects of dietary, drinking, and smoking habits on the prognosis of gastric cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2000;38:30-36.

14. Ramon J.M., et al. Dietary factors and gastric cancer risk. A case-control study in Spain. Cancer. 1993;71:1731-1735.

15. Devesa S.S., Blot W.J., Fraumeni J.F.Jr. Changing patterns in the incidence of esophageal and gastric carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 1998;83:2049-2053.

16. Gore R.M. Gastric cancer. Clinical and pathologic features. Radiol Clin North Am.. 1997;35:295-310.

17. Fenogilo-Preiser C., Carneiro F., Correa P., et al. Gastric carcinoma. In: Hamilton S., Aaltonin L. Pathology and Genetics. Tumors of the Digestive System. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2000:37-52.

18. Brooks-Wilson A.R., et al. Germline E-cadherin mutations in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: assessment of 42 new families and review of genetic screening criteria. J Med Genet.. 2004;41:508-517.

19. Yao J.C., et al. Gastric cancer. In: Jaffer S.A.C., Ajani A., Janjan N.A., Lynch P.M. Gastrointestinal Cancer. New York: Springer; 2004:219-231. MD Anderson Cancer Care Series

20. Vikram R., et al. Pancreas: peritoneal reflections, ligamentous connections, and pathways of disease spread. Radiographics. 2009;29:e34.

21. Gray H., Stomach .. Lewis W.H., editor. Anatomy of the Human Body, 20th ed., Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1918.

22. Borrman R. Geschwulste des Magens und Duodenums. In: Henke F., Lubarsch O. Handbuch der speziellen pathologischen Anatomie und Histologie. Berlin: Springer, 1926. :864-871

23. Jang H.J., et al. Intestinal metastases from gastric adenocarcinoma: helical CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:61-67.

24. Tanakaya K., et al. Metastatic carcinoma of the colon similar to Crohn’s disease: a case report. Acta Med Okayama. 2004;58:217-220.

25. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Stomach. In: Edge S.B., et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2010. :145-152

26. Siewert J.R., et al. Relevant prognostic factors in gastric cancer: ten-year results of the German Gastric Cancer Study. Ann Surg. 1998;228:449-461.

27. Roder J.D., et al. Classification of regional lymph node metastasis from gastric carcinoma. German Gastric Cancer Study Group. Cancer. 1998;82:621-631.

28. Yokota T., et al. Significant prognostic factors in patients with early gastric cancer. Int Surg. 2000;85:286-290.

29. Adachi Y., et al. Most important lymph node information in gastric cancer: multivariate prognostic study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:503-507.

30. Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma—2nd English Edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10-24.

31. Sobin L., Wittekind C. UICC TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors, 6th ed., New York: Wiley, 2002.

32. Brennan M.F. Current status of surgery for gastric cancer: a review. Gastric Cancer. 2005;8:64-70.

33. Karpeh M.S.Jr., Brennan M.F. Gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:650-656.

34. Halvorsen R.A.Jr., Yee J., McCormick V.D. Diagnosis and staging of gastric cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996;23:325-335.

35. Kunisaki C., et al. Outcomes of mass screening for gastric carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:221-228.

36. Bhandari S., et al. Usefulness of three-dimensional, multidetector row CT (virtual gastroscopy and multiplanar reconstruction) in the evaluation of gastric cancer: a comparison with conventional endoscopy, EUS, and histopathology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:619-626.

37. Kelly S., et al. A systematic review of the staging performance of endoscopic ultrasound in gastro-oesophageal carcinoma. Gut. 2001;49:534-539.

38. Hargunani R., et al. Cross-sectional imaging of gastric neoplasia. Clin Radiol. 2009;64:420-429.

39. Chen C.Y., et al. Gastric cancer: preoperative local staging with 3D multi-detector row CT—correlation with surgical and histopathologic results. Radiology. 2007;242:472-482.

40. Meyers M.A., editor. Dynamic Radiology of the Abdomen, 5th ed., New York: Springer-Verlag, 2000.

41. Lim J.S., et al. CT and PET in stomach cancer: preoperative staging and monitoring of response to therapy. Radiographics. 2006;26:143-156.

42. Mani N.B., et al. Two-phase dynamic contrast-enhanced computed tomography with water-filling method for staging of gastric carcinoma. Clin Imaging. 2001;25:38-43.

43. Takao M., et al. Gastric cancer: evaluation of triphasic spiral CT and radiologic-pathologic correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:288-294.

44. Kim Y.H., et al. Staging of T3 and T4 gastric carcinoma with multidetector CT: added value of multiplanar reformations for prediction of adjacent organ invasion. Radiology. 2009;250:767-775.

45. Horton K.M., Fishman E.K. Current role of CT in imaging of the stomach. Radiographics. 2003;23:75-87.

46. Sohn K.M., et al. Comparing MR imaging and CT in the staging of gastric carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:1551-1557.

47. Yoshioka T., et al. Evaluation of 18F-FDG PET in patients with advanced, metastatic, or recurrent gastric cancer. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:690-699.

48. Stahl A., et al. FDG PET imaging of locally advanced gastric carcinomas: correlation with endoscopic and histopathological findings. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:288-295.

49. Kamimura K., et al. Role of gastric distention with additional water in differentiating locally advanced gastric carcinomas from physiological uptake in the stomach on 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose PET. Nucl Med Commun. 2009;30:431-439.

50. Monig S.P., et al. Staging of gastric cancer: correlation of lymph node size and metastatic infiltration. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:365-367.

51. Motohara T., Semelka R.C. MRI in staging of gastric cancer. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:376-383.

52. Kim A.Y., et al. MRI in staging advanced gastric cancer: is it useful compared with spiral CT? J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2000;24:389-394.

53. Tatsumi Y., et al. Preoperative diagnosis of lymph node metastases in gastric cancer by magnetic resonance imaging with ferumoxtran-10. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:120-128.

54. Mawlawi O., et al. Performance characteristics of a newly developed PET/CT scanner using NEMA standards in 2D and 3D modes. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:1734-1742.

55. Yajima K., et al. Clinical and diagnostic significance of preoperative computed tomography findings of ascites in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2006;192:185-190.

56. Ozmen M.M., et al. Staging laparoscopy for gastric cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:241-244.

57. Dux M., et al. Helical hydro-CT for diagnosis and staging of gastric carcinoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:913-922.

58. Semelka R.C., et al. Focal liver lesions: comparison of dual-phase CT and multisequence multiplanar MR imaging including dynamic gadolinium enhancement. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13:397-401.

59. Chen J., et al. Improvement in preoperative staging of gastric adenocarcinoma with positron emission tomography. Cancer. 2005;103:2383-2390.

60. Tian J., et al. The value of vesicant 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) in gastric malignancies. Nucl Med Commun. 2004;25:825-831.

61. Tanaka T., et al. Usefulness of FDG-positron emission tomography in diagnosing peritoneal recurrence of colorectal cancer. Am J Surg. 2002;184:433-436.

62. Turlakow A., et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis: role of (18)F-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1407-1412.

63. Misra N., Harwick R., McCulloch P. Role of surgery in stomach cancer. In: McCulloch P., et al. Gastrointestinal Oncology. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2007:73-84.

64. Miyata M., et al. What are the appropriate indications for endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer? Analysis of 256 endoscopically resected lesions. Endoscopy. 2000;32:773-778.

65. Wang Y.P., Bennett C., Pan T. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.. 2006;1:CD004276.

66. Miura S., et al. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with systemic lymph node dissection: a critical reappraisal from the viewpoint of lymph node retrieval. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:933-938.

67. Strong V.E., et al. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a case-control study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1507-1513.

68. Yang S.H., et al. An evidence-based medicine review of lymphadenectomy extent for gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2009;197:246-251.

69. McCulloch P., et al. Extended versus limited lymph nodes dissection technique for adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.. 2004;4:CD001964.

70. Sasako M., et al. D2 lymphadenectomy alone or with para-aortic nodal dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:453-462.

71. Fiori E., et al. Palliative management of malignant antro-pyloric strictures. Gastroenterostomy vs. endoscopic stenting. A randomized prospective trial. Anticancer Res.. 2004;24:269-271.

72. Cooper J.S., et al. Chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced esophageal cancer: long-term follow-up of a prospective randomized trial (RTOG 85-01). Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. JAMA. 1999;281:1623-1627.

73. Earle C.C., Maroun J.A. Adjuvant chemotherapy after curative resection for gastric cancer in non-Asian patients: revisiting a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1059-1064.

74. Janunger K.G., Hafstrom L., Glimelius B. Chemotherapy in gastric cancer: a review and updated meta-analysis. Eur J Surg.. 2002;168:597-608.

75. Cunningham D., Chua Y.J. East meets west in the treatment of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1863-1865.

76. Sakuramoto S., et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1810-1820.

77. Kelsen D.P. Postoperative adjuvant chemoradiation therapy for patients with resected gastric cancer: intergroup 116. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(Suppl 21):32S-34S.

78. Murad A.M., et al. Modified therapy with 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and methotrexate in advanced gastric cancer. Cancer. 1993;72:37-41.

79. Pyrhonen S., et al. Randomised comparison of fluorouracil, epidoxorubicin and methotrexate (FEMTX) plus supportive care with supportive care alone in patients with non-resectable gastric cancer. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:587-591.

80. Vanhoefer U., et al. Final results of a randomized phase III trial of sequential high-dose methotrexate, fluorouracil, and doxorubicin versus etoposide, leucovorin, and fluorouracil versus infusional fluorouracil and cisplatin in advanced gastric cancer: a trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gastrointestinal Tract Cancer Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2648-2657.

81. Waters J.S., et al. Long-term survival after epirubicin, cisplatin and fluorouracil for gastric cancer: results of a randomized trial. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:269-272.

82. Kang Y.K., et al. Capecitabine/cisplatin versus 5-fluorouracil/cisplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomised phase III noninferiority trial. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:666-673.

83. Cunningham D., et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:36-46.

84. Shah M.A., et al. Multicenter phase II study of irinotecan, cisplatin, and bevacizumab in patients with metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5201-5206.

85. Kang Y., et al. AVAGAST: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study of first-line capecitabine and cisplatin plus bevacizumab or placebo in patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC). J Clin Oncol.; 2010. 28:18s

86. Pinto C., et al. Phase II study of cetuximab in combination with FOLFIRI in patients with untreated advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FOLCETUX study). Ann Oncol. 2007;18:510-517.

87. Lordick F., et al. Cetuximab plus oxaliplatin/leucovorin/5-fluorouracil in first-line metastatic gastric cancer: a phase II study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Br J Cancer. 2010;102:500-505.

88. VanCutsem E., et al. Efficacy results from the ToGA trial: a phase III study of trastuzumab added to standard chemotherapy (CT) in first-line human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive advanced gastric cancer (GC). J Clin Oncol.; 2009. 27:18s

89. Bang Y., et al. HER2-positivity rates in advanced gastric cancer (GC): results from a large international phase III trial. J Clin Oncol; 2008. 26

90. Ikeda Y., et al. Effective follow-up for recurrence or a second primary cancer in patients with early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:235-239.

91. Tan I.T., So B.Y. Value of intensive follow-up of patients after curative surgery for gastric carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:503-506.

92. Whiting J., et al. Follow-up of gastric cancer: a review. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:74-81.

93. Ha H.K., et al. Local recurrence after surgery for gastric carcinoma: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:975-977.

94. Kinkel K., et al. Detection of hepatic metastases from cancers of the gastrointestinal tract by using noninvasive imaging methods (US, CT, MR imaging, PET): a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2002;224:748-756.