Gastrectomy

Surgical Approach for Gastrectomy

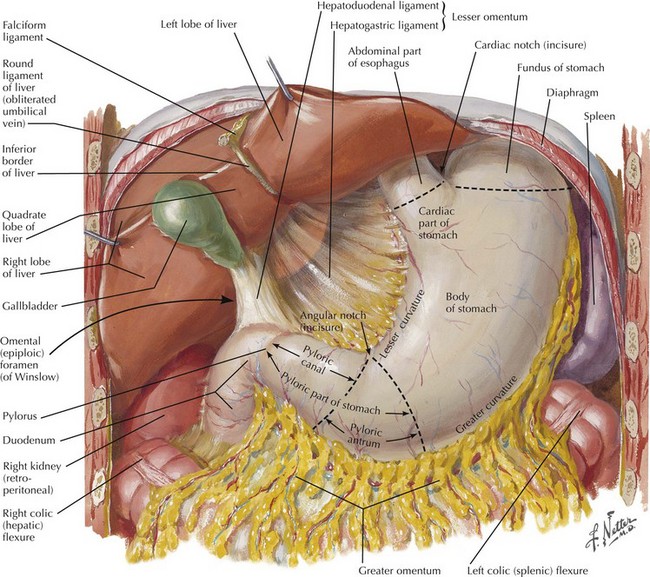

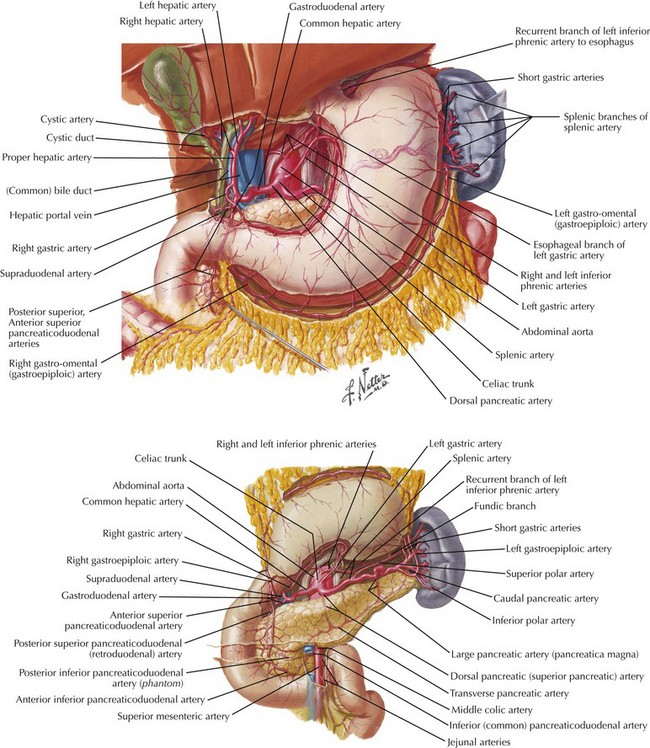

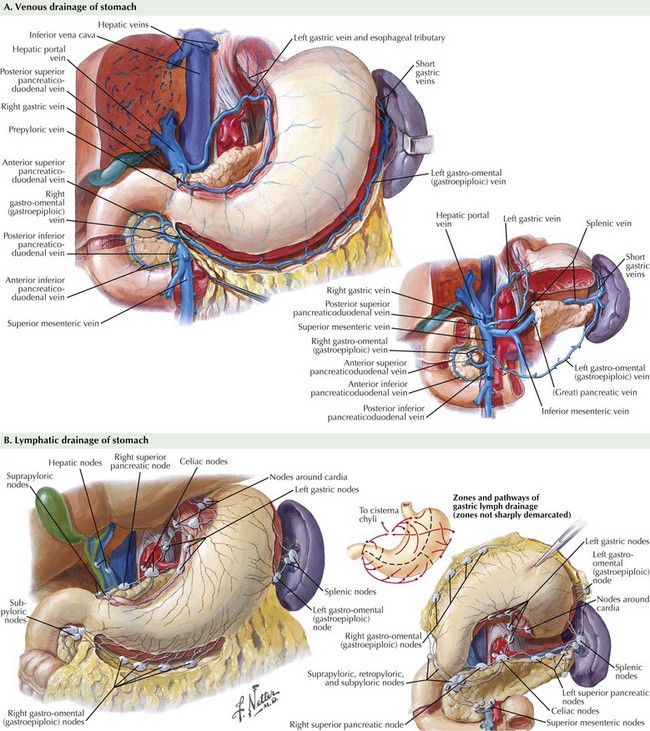

The abdomen is explored to evaluate for metastatic disease, usually through an upper midline incision, although some surgeons prefer a chevron incision. Laparoscopic-assisted approaches to gastric resection are increasingly used. Figure 8-1 shows the stomach in situ with its relationship to surrounding structures. Figures 8-1, 8-2, and 8-3, A, show the arterial and venous anatomy pertinent to gastric resection.

Once disseminated disease is excluded, dissection begins with mobilization of the stomach. The lesser sac is entered by taking the omentum off the transverse colon, keeping the omentum with the stomach. This approach provides wide exposure of the posterior aspect of the stomach and lesser sac (Figs. 8-2 and 8-3) and allows the surgeon to assess for any posterior invasion by the tumor.

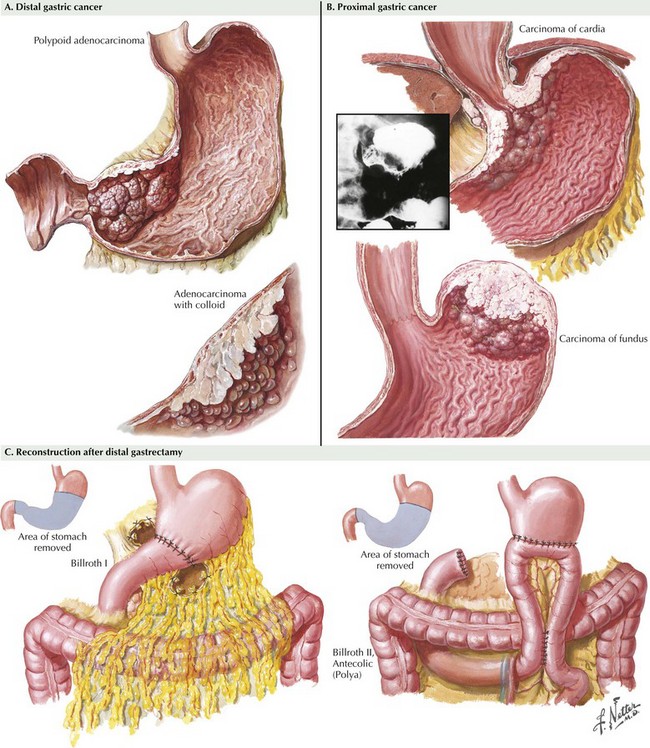

At this point, an assessment is made as to the extent of resection that will be required. Distal tumors (Fig. 8-4, A) are treated with distal/subtotal gastrectomy, and proximal tumors (Figure 8-4, B with total gastrectomy. Achieving negative margins for tumors along the lesser curvature of the stomach is more difficult than for tumors along the greater curvature of the stomach; thus, lesser curve tumors more often require total gastrectomy.

The duodenum is divided with a surgical stapler. The duodenal stump may be left as a simple staple line, or it may be oversewn by using simple Lembert sutures or by burying the staple line and suturing the duodenum to the capsule of the pancreas. The left gastric artery is taken at its origin; in some patients, this is best done along the lesser curvature of the stomach or with the stomach retracted cranially (see Fig. 8-2). Proximal transection is achieved with multiple firings of the surgical stapler. If a total gastrectomy is performed and a circular-stapler anastomosis is planned, the purse-string staple device may be used for the proximal transection. Both proximal and distal margins are assessed through frozen section, and further resection is undertaken if necessary.

While performing the resection, the surgeon must be cognizant not only of margins but also of the extent of lymphadenectomy. Figure 8-3 highlights the 16 lymph node basins. A D1 lymphadenectomy refers to removal of the perigastric lymph nodes. A D2 lymphadenectomy adds removal of nodes along the left gastric, celiac, and splenic arteries, as well as the nodes in the splenic hilum. A D3 lymphadenectomy adds removal of nodes in the hepatic portal (porta hepatis) and the periaortic regions.

Controversy persists regarding the appropriate extent of lymphadenectomy, with the competing issues being appropriate staging and survival benefit versus increased surgical morbidity and mortality. Two Western prospective randomized trials have shown no survival benefit when doing a D2 versus a D1 lymphadenectomy, while having greater morbidity associated with the D2 dissection (see Suggested Readings). Despite this, treatment guidelines published by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend a D2 versus a D1 lymphadenectomy.

Reconstruction after a distal gastrectomy is usually accomplished with a Billroth II gastrojejunostomy (Fig. 8-4, C). This instrument is generally favored over a Billroth I (gastroduodenostomy) reconstruction because of concerns regarding anastomotic tension as well as potential tumor recurrence. Reconstruction after a total gastrectomy may be performed with either a Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy or a loop esophagojejunostomy with a distal enteroenterostomy, with the hope of diverting bile and pancreatic juice from the esophagus. Some favor formation of a jejunal pouch as a “neostomach,” but this has shown no clear benefit. For either a distal or a total resection, the jejunum may be brought up for reconstruction in an antecolic or a retrocolic manner. Drains are not routinely placed after a gastrectomy.

Bonenkamp, JJ, Hermans, J, Sasako, M, van de Velde, CJ. Extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:908.

Cunningham, D, Allum, WH, Stenning, SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11.

Cuschieri, A, Fayers, P, Fielding, J, et al. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: preliminary results of the MRC randomised controlled surgical trial. Lancet. 1996;347:995.

Cuschieri, A, Weeden, S, Fielding, J, et al. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1522.

Hartgrink, HH, van de Velde, CJ, Putter, H, et al. Extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: who may benefit? Final results of the randomized Dutch Gastric Cancer Group trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2069.

MacDonald, JS, Smalley SR Benedetti, J, et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725.