Gallstones

Introduction

In the UK it has been estimated from autopsy studies that approximately 12% of men and 24% of women of all ages have gallstones present.1 The prevalence in North America is comparable to that in the UK, and it is believed that 10–30% of gallstones become symptomatic. There is a high prevalence in native Americans, who have an incidence of 50% in men and 75% in women in the age group 25–44 years, and this points to the importance of genetic factors in the aetiology of gallstones. In the UK more than 40 000 cholecystectomies are performed each year,2 whereas in the USA approximately 500 000 operations are performed annually.3 The incidence of common bile duct stones found before or during cholecystectomy is approximately 12%,4 indicating that in the UK alone more than 4000 common bile ducts require stone clearance annually.

Composition, formation and risk factors

Gallstones are usually designated as cholesterol stones, mixed stones or pigment stones.5 Pure cholesterol and pure pigment stones account for only 20% of gallstones, and mixed stones are considered as variants of cholesterol stones as they usually contain over 50% cholesterol and account for about 80% of gallstones in Western countries. Chemical analysis shows a continuous spectrum of stone composition rather than three mutually exclusive stone types, and 10–20% contain enough calcium to be rendered radio-opaque.

The two most important determinants of gallstone frequency in any population are age and gender; gallstones become more common with increasing age and are at least twice as common in women.6 The increased frequency in women becomes manifest at puberty, and an increased risk of gallstones is conferred by parity and by the ingestion of oral contraceptives.7 Other factors related to the development of cholesterol gallstones include obesity, ileal disease or resection, cirrhosis, cystic fibrosis, diabetes mellitus, long-term parenteral nutrition, impaired gallbladder emptying, ingestion of clofibrate,8 heart transplant,9 and periods of dieting on a very low fat diet.10 A positive family history of previous cholecystectomy also increases the risk of developing symptomatic gallstone disease.11 Increasing evidence is emerging that impaired colonic motility contributes to stone formation, and speculation arises for this as a means of prevention.12

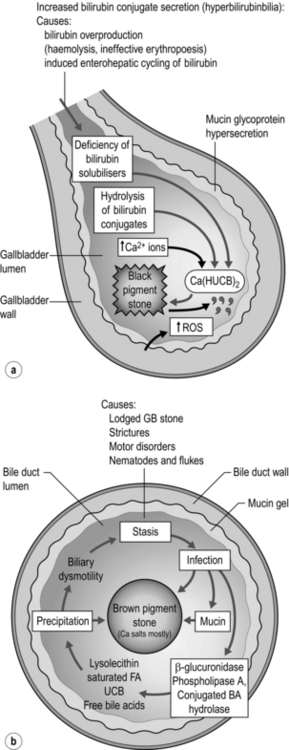

Pigmented gallstones are composed mainly of calcium hydrogen bilirubinate, in a polymerised and oxidised form in ‘black’ stones and in unpolymerised form in ‘brown’ stones. Black stones form in sterile gallbladder bile, but brown stones form secondary to stasis and anaerobic infection in any part of the biliary tree (Fig. 10.1).

Figure 10.1 Schematic outline of the pathogenesis of ‘black’ pigmented stones in sterile gallbladder bile (a) and ‘brown’ pigmented stones in an obstructed biliary tree (gallbladder infrequently) infected with a mixed anaerobic microflora derived from the colon (b). Adapted from Vitek L, Carey MC. New pathophysiologic concepts underlying pathogenesis of pigment gallstones. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2012; 36(2):122–9.

Brown stones form in any part of the biliary tree from any cause of chronic stasis and anaerobic infection. Anaerobes secrete enzymes that hydrolyse ester and amide linkages in biliary lipids into calcium-sensitive anions that phase separately as insoluble anions or calcium salts. These precipitates deposit on obstructing elements such as small cholesterol crystals, black stones from the gallbladder, parasite eggs and dead worms or flukes. Oriental hepatolithiasis syndrome is the most serious manifestation of brown pigment stone disease.13

Presentation

Choledocholithiasis

It is uncertain whether all common bile duct (CBD) stones produce symptoms. It is traditionally held that the CBD cannot produce colicky pain as it does not contain smooth muscle, but pain in the right upper quadrant following cholecystectomy may be a sign of retained bile duct stones. A stone impacted in the lower end of the CBD may also be associated with nausea and vomiting, and undoubtedly the muscular spasms of the sphincter of Oddi or duodenum could account for the pain that is often felt radiating through to the back. Obstructive jaundice results when a stone becomes impacted within the CBD, in the tapered portion within the pancreas or ampulla. A stone may pass spontaneously or fall back into the CBD (‘ball-valving’) with spontaneous regression of the jaundice, or it may remain impacted until it is removed. A stone at the lower end of the CBD may also cause pancreatitis by temporary obstruction of the pancreatic duct, and this may be associated with transient jaundice (see Chapter 13). Ascending cholangitis results from infection within an obstructed or poorly draining biliary system. In patients with CBD stones, coliforms are identified within the bile in around 80% of cases.14 The classic Charcot’s triad of symptoms produced by bile duct stones with cholangitis consists of pain, obstructive jaundice and fever (with or without rigors). Acute cholangitis may progress to acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis with pain, obstructive jaundice, fever, hypotension and mental obtundation (Reynolds’ pentad) requiring early recognition and prompt endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) drainage to save life.15

Investigation

Blood tests

Liver function tests (LFTs) should be performed routinely in patients with suspected gallstones. Although these may not be affected by the presence of cholecystolithiasis, they may be abnormal in the presence of choledocholithiasis. An isolated increase of unconjugated bilirubin is present in prehepatic jaundice such as is seen with excessive haemolysis. The biochemical picture of hepatic jaundice, as seen with hepatitis, is one of raised conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin, high aspartate (AST) and alanine (ALT) transaminase levels, but associated with a relatively normal or slightly raised alkaline phosphatase (ALP). Posthepatic (obstructive) jaundice is associated with a raised conjugated bilirubin only, high ALP, and normal AST and ALT. In late cases of obstructive jaundice or in acute cholangitis, the transaminase levels will rise as hepatocellular damage proceeds. Minor abnormalities in the LFTs occur with non-obstructing stones in the CBD. These minor abnormalities may prompt the undertaking of an operative cholangiogram at the time of surgery if a selective operative cholangiogram policy is being pursued.16,17

Approximately 60% of patients with CBD stones (including asymptomatic stones) will have one or more abnormal LFTs, although a substantial number of patients with an abnormal LFT will not have CBD stones. Bilirubin, ALP and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) are the most sensitive tests routinely used.18 In the acute situation, a serum amylase or lipase level should also be ascertained to exclude a diagnosis of pancreatitis, and a raised white blood cell count may support a clinical diagnosis of acute cholecystitis.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound is the investigation used most widely to confirm the diagnosis of cholelithiasis. It is easy to perform, causes little discomfort to the patient, avoids irradiation and potentially toxic contrast media, and may be useful in demonstrating and assessing other structures in the upper abdomen. The gallbladder wall, as well as its contents, can be assessed and this may give additional information useful for planning management. CBD stones may be harder to identify, although the presence of a dilated CBD and small stones within the gallbladder give clues as to their presence. If the gallbladder cannot be identified, the presence of an echogenic focus in the gallbladder area is nearly as specific a finding as that of calculi in a distended gallbladder. With high-quality ultrasound scanning, gallstones should be detected in at least 95% of patients with stones. Its reliability in detecting CBD stones varies between 23% and 80% depending on body habitus and experience of the ultrasonographer.19

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)

Prat et al. have reported EUS with a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 97% in detecting CBD stones, showing some promise of approaching values achieved by ERCP (89% and 100%).20 EUS has also been reported as more sensitive than the transabdominal approach. Norton and Alderson reported confirmation of gallstone disease in 15 of 44 patients with ‘idiopathic’ pancreatitis who underwent EUS.21

Computed tomography (CT)

CT may be more accurate than ultrasound in identifying CBD stones, with a sensitivity of 75% for CBD stones causing obstructive jaundice.22 However, the relatively low rate of gallbladder stone detection may be due, in part, to cholesterol stones being isodense with bile on CT. The newer generation spiral CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be better but their potential advantage over abdominal ultrasound scanning is not readily apparent. Spiral CT following intravenous infusion cholangiography has been shown to allow accurate reconstruction of cystic duct/CBD anatomy and providing severe jaundice is not present rivals magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) in its capacity to outline CBD stones.23

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)

Fast image acquisition in a few seconds and improved software have allowed imaging of the biliary and pancreatic tree in enough detail to approach the resolution of ERCP.24 The technique relies on the principle of imaging fluid columns that are static and so give detail of bile and static fluid in the duodenum and stomach. Better images are obtained with dilated ducts, and bile flow can be a source of error in false-positive stone detection. The presence of CBD calculi can be detected with a sensitivity of 95%, specificity of 89% and accuracy of 92%. The ability to detect anatomical variation of the extrahepatic bile ducts is less established.25 Following standard non-invasive tests, Liu et al. stratified suspicion of CBD stones into four categories. Patients at extremely high risk of CBD stone underwent ERCP. Patients at high risk underwent MRCP followed by ERCP if stones were seen. With diagnostic accuracies greater than 90% many patients were spared unnecessary ERCP.26

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

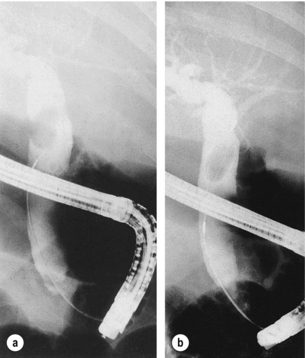

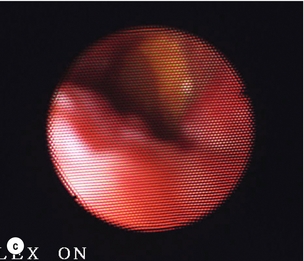

ERCP is considered the gold standard in preoperative CBD imaging. With direct visualisation of the papilla using a side-viewing duodenoscope, the papilla can be cannulated selectively to provide images of both the pancreatic and common bile ducts. Water-soluble contrast medium is injected to outline the biliary tree, and offers the advantage over other biliary tree imaging techniques of therapeutic intervention with sphincterotomy and stone extraction at the time of examination (Fig. 10.2). The role of ERCP in the management of CBD stones is discussed later in this chapter.

Management of gallbladder stones

There has been much debate regarding the need for surgical intervention in patients with asymptomatic gallstones. In one American study, which assessed the natural history of subjects with asymptomatic stones, individuals with gallstones were diagnosed by ultrasound scan on entry to a large university healthcare plan.27 Only 2% of patients with incidentally diagnosed gallstones became symptomatic each year and presented with biliary colic or cholecystitis rather than the more serious complications of jaundice, empyema or cholangitis.27 Only 10% of the asymptomatic patients, followed for a mean of almost 5 years by McSherry and Glenn, developed symptoms, and only 7% required operation.28 Although stones are undoubtedly associated with an increased risk of gallbladder cancer, only one of the 691 gallstone patients followed in this study was found eventually to have an incidental carcinoma at operation, and further data are required to clarify this issue.

Recent Swedish population postcholecystectomy follow-up data after a mean of 15 years revealed a weak increased risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma with a standardised incidence ratio of 1.29. This is hypothesised to be due to increased oesophageal bile acid exposure.29

Further randomised data have revealed that surgery remains the best treatment for symptomatic gallstones, but conservative management may in selected circumstances be used in the elderly.30

Non-operative treatments for gallstones

In the early 1970s there was great interest in the use of dissolution agents, principally chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), in the treatment of gallstones.31 Prerequisites for attempting dissolution therapy were a functioning gallbladder, multiple small stones (which have a greater total surface area for contact with the dissolution agent rather than a smaller number of larger stones) and radiolucency (indicative of pure cholesterol stones without a calcium or pigment matrix to impede dissolution). Success was slow to be achieved in most subjects, usually taking 6–12 months as judged by the disappearance of stones on ultrasound. Side-effects of treatment included abdominal cramps, diarrhoea and occasional LFT abnormalities. Ursodeoxycholate (UDCA) has been shown to be equally effective as CDCA in dissolving gallstones. In patients administered dissolution agents, O’Donnell and Heaton32 found that recurrence rates increased rapidly in the first few years, with rates of 13% at 1 year, 31% at 3 years, 43% at 4 years and 49% at 11 years. Although recurrent stones were readily redissolved, they generally recurred when therapy ceased.

Lithotripsy

Success with lithotripsy for renal stones led to the use of the same techniques for gallbladder stones. Early lithotripters, with immersion in large water baths, were soon succeeded by smaller devices with a limited area of contact via a water-filled cushion. Biliary anatomy, however, did not lend itself to a repeat of the success observed with renal stones. The tidal flow of bile into and out of the gallbladder, along with the presence of multiple gallstones, were factors that contributed to the failure of the technique. Ahmed et al.33 reported that 45% of patients undergoing lithotripsy required subsequent cholecystectomy. Lithotripsy has therefore been retained only for the management of ductal stones resistant to endoscopic removal.34

Operative treatment of gallbladder stones

The operative mortality of open cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis had fallen in the years before the introduction of laparoscopic surgery, with many series reporting operative mortality rates of less than 1%.35 Common duct exploration was regarded as increasing the risk of open cholecystectomy by four- to eight-fold.36 In a comparative study between a North American and a European centre, 12–14% of patients developed complications, and the bile duct was explored in 8.6% of the patients in Toronto as opposed to 17.9% in Geneva, the incidences of positive exploration being 61% and 73%, respectively. Factors increasing the risk of postoperative mortality were advancing age, acute admission, admission to hospital within 3 months of the index admission, and the number of discharge diagnoses.36 Only 18% of postoperative deaths in this study were related to the gallstone disease or the surgery, with underlying cardiovascular or respiratory disease contributing to 48% of deaths.

There has been considerable uncertainty regarding the true incidence of bile duct injury at open cholecystectomy, and the surveys available cite figures of one injury per 300–1000 operations.37 At cholecystectomy, injury results from imprecise dissection and inadequate demonstration of the anatomical structures.38 Although some patients do have anatomical anomalies or pathological changes that increase the risk of duct injury, it is noteworthy that in the extensive Swedish review, the patients most at risk appeared to be young, slim females who had not undergone previous surgery.37

In a detailed analysis of a consecutive group of patients undergoing cholecystectomy for presumed biliary pain in a District General Hospital between 1980 and 1985, Bates et al.39 compared the outcome of an age- and sex-matched control group of surgical patients without gallstone disease. Flatulent dyspepsia was more frequent in gallstone patients but operation markedly reduced these symptoms to an incidence almost identical to that of the control group. However, within 1 year of cholecystectomy, no less than 34% of patients still suffered some abdominal pain and none of the 35 patients referred back to hospital for investigation had evidence of retained ductal stones. Multivariate analysis showed that preoperative flatulence and long durations of attacks of pain were risk factors for postoperative dissatisfaction.

Mini-laparotomy cholecystectomy

There have been few controlled trials; of those that have been performed, one showed laparoscopic cholecystectomy to be superior and the other showed mini-laparotomy cholecystectomy as superior.40,41 The most recent randomised trial has again confirmed a smoother convalescence for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, although operating times remained longer.42

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Symptomatic gallstones: The laparoscopic procedure can be offered to all patients with symptomatic gallstones, providing their cardiorespiratory status does not preclude laparoscopy. Of all patients presenting for operation, 95% can be completed successfully by laparoscopic means. Obesity, acute inflammation, adhesions and previous abdominal surgery do not usually prevent a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, but may require some adaptations of technique to complete the procedure.43–51 Techniques of laparoscopic cholecystectomy have been well described previously,43,44 including cases performed under regional anaesthesia in patients with chronic pulmonary disease.45 Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been widely reported in pregnancy46 and in patients with cirrhosis.47 In a substantial audit of seven European centres,43,44 96% of procedures were completed successfully in the 1236 patients and only four bile duct injuries were reported. There were no postoperative deaths, median hospital stay was 3 days and the median return to normal activities was only 11 days.

Acute cholecystitis: Fears that laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the management of acute cholecystitis could carry an unacceptable risk of disseminating infection or of perpetrating an injury to the bile duct appear unfounded.51 Several large series report success and safety with this procedure, although the incidence of bile duct injury and conversion to open operation remain slightly higher.52 In difficult cases, improvement in the exposure of Calot’s triangle may require additional or different positioning of the laparoscopic cannulae, the use of oblique viewing telescopes and placement of endoscopic retractors. Decompression of a distended or inflamed gallbladder may also improve access.

Complications: The mortality rate in a good-risk patient undergoing elective operation is less than 1% and operative risks usually arise from comorbid conditions. The laparoscopic technique is associated with lower wound infection rates than open surgery.53 Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis has shown that antibiotic prophylaxis is not warranted in low-risk patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy.54

Day-case laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Worldwide, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is being performed in the day-case setting with good preoperative patient selection, improved techniques, and improved postoperative control of pain, nausea and vomiting.55

Needlescopic cholecystectomy: This technique has been described using 2- and 3-mm instruments and a 3-mm laparoscope. A randomised trial has shown less pain and smaller scars when this technique was used in patients with chronic cholecystitis.56

Evolution of technical aspects of multiport exposure, decreasing port sizes and instrumentation continues. There is currently no evidence of a benefit for single-incision laparoscopic port techniques,57 with impaired ergonomic performance and probable increased incisional hernia rate.

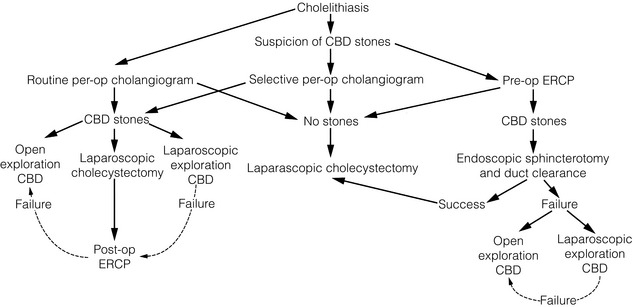

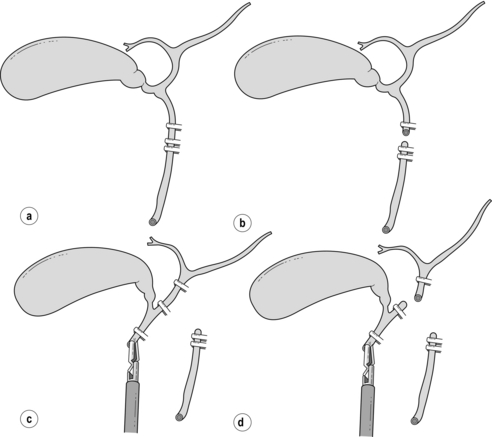

Bile duct injury: Anxieties regarding an increased incidence of bile duct injury with the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy have not been substantiated by multicentre studies from Europe48 and the USA,49 with a reported incidence of injury to the CBD of 1 in 200–300 cases. In a study in the West of Scotland, a prospective audit of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was undertaken.58 A total of 5913 laparoscopic cholecystectomies were undertaken by 48 surgeons, and 37 laparoscopic bile duct injuries were reported. Major bile duct injuries were defined as those where laceration to more than 25% of the bile duct diameter occurred, where the common hepatic duct or CBD was transected, or in those instances when a bile duct stricture developed in the postoperative period. Of the 37 injuries, 20 were classified in this way, giving an incidence of 0.3%. Delayed identification of bile duct injury occurred in 19 patients and, although it was noted by the author that cholangiography did not play a part in the identification of bile duct injuries, it was noteworthy that imaging was used in only 8.8% of all laparoscopic procedures. During the course of this 5-year study, the annual incidence of bile duct injury peaked at 0.8% in the third year but had fallen to 0.4% in the final year of the audit. A meta-analysis of more than 100 000 cases reported an injury rate of 0.5%.59 Archer et al. emphasised the importance of supervised surgical training to allow attenuation of the trainee surgeon’s learning curve by the experience of his/her proctoring surgeon. The importance of cholangiography in the early detection of bile duct injury was also emphasised.60 Way et al. analysed bile duct injuries from a cognitive psychological perspective and concluded that errors that led to bile duct injury stemmed from anatomical misperceptions as opposed to errors of skill or judgment (Fig. 10.3). This analysis concluded with a list of rules to help prevent injuries.61

Figure 10.3 The ‘classical’ laparoscopic bile duct injury. (a) The common duct is misidentified as the cystic duct and is doubly clipped. (b) The common duct is then divided. (c) The gallbladder is retracted to the right, stretching the common hepatic duct and placing it in contact with the gallbladder. This is identified as an accessory duct and double clipped. (d) A high transection of the common hepatic duct results in the excision of most of the extrahepatic biliary tree.

Cholecystostomy

For patients whose symptoms of acute cholecystitis did not settle in the past, cholecystostomy was often undertaken in those cases where open cholecystectomy was thought to carry an unacceptable risk of injury to the biliary tree. The procedure could be undertaken under local anaesthesia and, following decompression of the gallbladder and stone removal, a drain could be left in situ. With the demonstration that acute cholecystectomy could be undertaken safely,52 cholecystostomy has become an infrequent surgical procedure. The technique now is most often undertaken percutaneously under ultrasound or CT guidance and is most used in the frail patient with cardiorespiratory instability requiring time to control or when anticoagulation precludes surgery. It may rarely be of value during a difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy when the risk of conversion to an open procedure may be considered unacceptable. In such instances, a drain can be inserted through one of the 5-mm cannulae, which can be introduced directly into the gallbladder by reinsertion of a trocar.

Intraoperative cholangiography (IOC)

Routine IOC: Many surgeons who had previously performed the technique routinely at open cholecystectomy abandoned cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy, since it was thought to be too difficult to undertake. In a large population-based study in Western Australia, Fletcher et al.63 concluded that operative cholangiography had a protective effect for complications of cholecystectomy. In a large study of over 1.5 million Medicare patients undergoing cholecystectomy, Flum et al.64 demonstrated that surgeons performing operative cholangiography routinely had a lower rate of bile duct injuries than those who did not, and this difference disappeared when IOC was not used. The author believes that operative cholangiography has an important role in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, not only to detect CBD stones but also to confirm, beyond doubt, the anatomy of the biliary tree, since the severity of bile duct injury appears far greater in laparoscopic surgery. The addition of cholangiography to the total dissection time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy is relatively short. On the basis that the time to learn operative cholangiography is not during the management of a difficult case, it is recommended that it should be performed as a routine but should not be seen as a substitute for careful dissection of the infundibulum of the gallbladder and the cystic duct close to the gallbladder. By dissecting these structures both anteriorly and posteriorly, the gallbladder is displaced (sometimes called the ‘flag’ technique, or ‘critical view’) to enable the surgeon to see behind the gallbladder and thus minimise the risk of injury to the portal structures. Routine IOC also improves the surgeon’s skills to enable successful transcystic exploration of the CBD.

Selective IOC: There are data supporting a selective approach to IOC at open17 and laparoscopic cholecystectomy.65 Unsuspected stones on routine cholangiography at laparoscopic cholecystectomy occurred in only 2.9%, and residual CBD stones causing symptoms in patients not undergoing routine cholangiography were found in only 0.30%. The strength of any selective policy for IOC will depend on the predictive values of preoperative investigations. Numerous studies have examined risk factors for choledocholithiasis but, from multivariate analysis, it would appear that an increased diameter of the CBD and the presence of multiple (> 10) gallstones are the only significant independent indicators.17

Bile duct injury

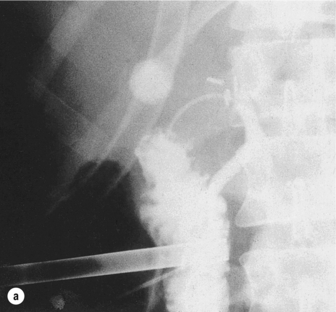

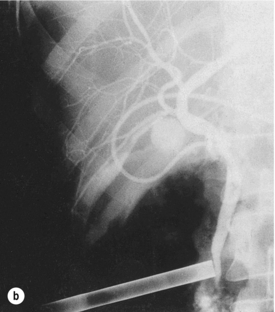

The principal cause of damage is due to misidentification of the CBD as the cystic duct. As dissection proceeds an ‘accessory duct’ (in reality the common hepatic duct) is visualised, clipped and divided, resulting in resection of most of the extrahepatic biliary tree (Fig. 10.3). Operative cholangiography adds to the certainty that the cannula is in the cystic duct. If only the distal biliary tree is filled, the surgeon is alerted to the error before any duct is completely divided. Although critics of operative cholangiography will argue that the CBD has been injured by the incision through which the cholangiogram catheter is introduced, the injury at this point is recoverable, either by direct suture or insertion of a T-tube (Fig. 10.4). In the rarer situation when the cystic duct arises from the right hepatic duct, and dissection has not progressed correctly, cholangiography identifies such anomalies and helps to avert more major injury (Fig. 10.5).

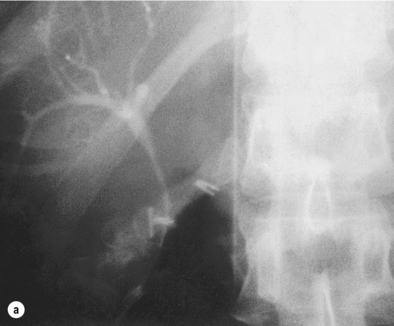

Figure 10.4 (a) The small-diameter common bile duct has been mistaken for the cystic duct. Only the distal common bile duct and duodenum are shown, with no proximal filling of the ducts. Recognition of the error at this stage averts a major injury to the common duct. (b) After further dissection, the cystic duct was identified and a T-tube placed in the incision in the common duct. A subsequent T-tube cholangiogram confirms the normal anatomy, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy was completed successfully.

Figure 10.5 (a) During what appeared to be a very straightforward laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the routine operative cholangiogram showed only the right hepatic duct and right hepatic biliary tree. (b) Repositioning of the catheter and the LigaClip showed the remainder of the biliary tree and made clear that the structure initially thought to be the cystic duct was the distal right hepatic duct below an anomalous origin of the cystic duct.

Laparoscopic ultrasound (LUS)

The emergence of ultrasound probes that can be passed down the laparoscopic ports has further improved the accurate measurement of CBD diameter, as well as the stone load within the gallbladder. Both mechanical sectoral and linear array laparoscopic ultrasound probes have been shown to be as useful as cholangiography in the detection of CBD stones.66,67 LUS is less invasive, less time-consuming, allows less radiation exposure and has similar failure rates to IOC when performed in well-trained hands. In a large series, the common hepatic duct and the CBD were identified in 93% and 99% of cases, respectively. Sensitivity and specificity for identifying bile duct stones were 92% and 100%, respectively. A normal CBD diameter at LUS was also an excellent negative predictor of CBD stones.68 The same authors later concluded that LUS could replace IOC.69 Others feel IOC and LUS should be seen as complementary tests rather than competitive.70 LUS may facilitate a policy of selective cholangiography. Despite reports of accurate identification of anatomy it remains to be seen whether this will translate to prevention of bile duct injury. A cost benefit also remains to be demonstrated, given the capital outlay for the equipment.

Management of common bile duct stones

The natural history of a given CBD stone remains difficult to predict. In a prospective study of 1000 cases of symptomatic gallstones it was found that 73% of cases that presented with features suggestive of CBD stones had no CBD stone at the time of operation and were therefore considered to have passed the stone spontaneously. Cases of cholangitis or jaundice were less likely to pass stones spontaneously.71

Primary bile duct stones form within the CBD, usually due to ampullary stenosis, diverticula or impaired bile duct motility. Management of these stones will often require choledochojejunostomy, depending on the circumstances and patient age.72,73 Treatment of primary duct stones with choledochotomy and T-tube drainage alone is associated with recurrence rates up to 41%.74 Laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy remains an option for the advanced laparoscopic surgeon,75,76 although there may be concerns regarding the longer-term consequences of bilioenteric reflux.

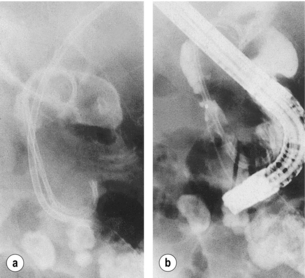

The best management of CBD stones is still a matter of debate.77 Discussion of different practices is presented here in the order the author considers most practical, and a suggested algorithm is presented.

Laparoscopic transcystic common bile duct exploration

Laparoscopic CBD exploration has been described through the cystic duct or common duct using either fibreoptic instruments or radiologically guided wire baskets or balloons.78–81 The increased emphasis on improving techniques via the transcystic route is because of the ease of closure without the added need for intracorporeal suture technique, combined with postoperative recovery similar to cholecystectomy alone. Careful evaluation of the CBD diameter and stone load from the cholangiogram is required to determine the best approach.

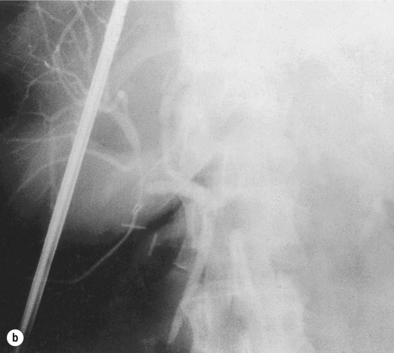

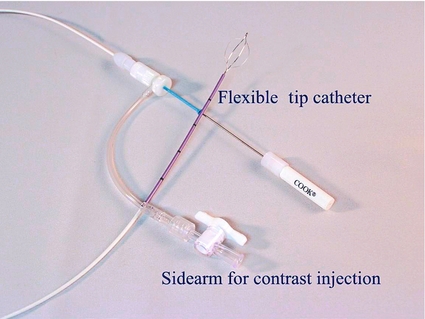

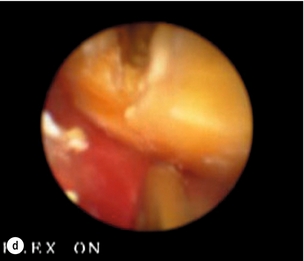

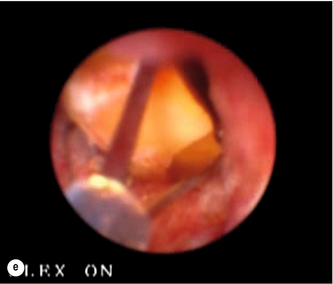

The author’s preferred initial method of laparoscopic exploration is by fluoroscopic means using a C-arm image intensifier, which is mobile and provides dynamic images with angulation. We employ a 5.5-Fr 70-cm radio-opaque nylon catheter with soft tip and end hole along with a side arm that connects to a catheter for injection of contrast (Fig. 10.6). Once the cystic duct is opened for insertion of the cholangiogram catheter, absence of bile backflow is a signal to milk the cystic duct backwards to extrude stones caught in transit to the CBD, rather than push them onwards into the CBD. A cholangiogram is performed (Fig. 10.7a), note being taken of the cystic duct and bile duct diameter, number of stones, stone size and their distribution in the biliary tree. CBD stones that appear to be of a size suitable for removal via the cystic duct and are not too numerous indicate that transcystic clearance has a high chance of success. Transcystic clearance proceeds by passing a 75-cm-long stone extractor (Cook®, Wilson-Cook Medical GI Endoscopy Inc., North Carolina). The basket tip should be positioned well back from the cannula tip to avoid perforation of the duct. Once the cannula tip is progressed, under image intensification, the basket is advanced within the cannula to allow engagement of the stone, which is withdrawn into the basket and extracted via the cystic duct (Fig. 10.7b). It is useful to remove the proximal stones first, and vital to avoid opening the basket within the duodenum or withdrawing through the ampulla with the basket wires open. Any impacted stones can be dislodged by passing a 4-Fr Fogarty catheter beyond the stone and withdrawing the catheter with the balloon inflated. Failed disimpaction may require choledochoscopy and lithotripsy (Fig. 10.7c–f, Box 10.1).

Figure 10.6 Composite cholangiogram catheter and stone extraction basket used for laparoscopic transcystic exploration of the common bile duct. Reproduced with permission of Cook Australia.

Figure 10.7 (a) Cholangiogram of a 21-year-old jaundiced patient demonstrating multiple CBD stones with one impacted 3 cm proximal to ampulla. (b) Fluoroscopic view of bile duct showing after rapid transcystic four-wire basket retrieval of all except the impacted stone. (c) Transcystic choledochoscopic view of impacted stone, unable to be dislodged with a balloon catheter. (d) Transcystic ureteroscopic lithoclast stone fragmentation. (e) Wire basket stone retrieval under vision. (f) Fluoroscopic view of cleared bile duct.

There is accumulating evidence, including three randomised trials, that 60–70% of patients are able to have their calculi cleared via the cystic duct.82–88

Laparoscopic choledochotomy

In up to 35% of patients, laparoscopic transcystic exploration of the CBD will fail to clear the CBD.82–88 Choledochotomy then needs to be considered. The only absolute contraindication to choledochotomy is a CBD diameter of less than 8 mm (Box 10.2). It should also be borne in mind that approximately one-third of stones detected at cholangiography may be passed spontaneously, and that exploration of a small duct may result in increased morbidity for the patient.89 Therefore, laparoscopic choledochotomy is only an option for appropriately trained surgeons (Box 10.3).

Once clearance of the duct has been confirmed by choledochoscopy (see below), a T-tube is inserted or primary closure can be considered with the insertion of an antegrade stent across the ampulla.82 Antegrade stenting, placement of a T-tube or cystic duct tube decompression of the CBD is wise where doubt exists about free postoperative bile drainage through the ampulla. This is most likely where a stone was impacted, ampullary manipulation has been extensive or in patients with established cholangitis. Placement of a subhepatic drain is essential.

Open choledochotomy

Successful exploration of the CBD can only be achieved through an adequately sized choledochotomy to facilitate both removal of any obvious stones and choledochoscopy. The gradual adoption of operative choledochoscopy during the 1970s and 1980s saw a decline in the incidence of retained CBD stones following surgery, from about 10% to 1.2%, with a number of surgeons reporting large series of patients with no retained stones.90 On initial examination of the proximal ducts, it is normally possible to visualise several generations of ducts when these are dilated. Once it has been ascertained that the upper ducts are clear, the distal biliary tree can be examined. It is mandatory to clearly visualise the rather ragged appearance of the ampulla of Vater and then withdraw the choledochoscope. If a stone is visualised it can be retrieved with a stone basket and the procedure repeated until the duct is clear. The common duct is closed with or without a T-tube.91 The latter is probably unnecessary for an experienced choledochoscopist but, for the less experienced surgeon, it allows access to the biliary tree for postoperative cholangiography to confirm ductal clearance and to allow re-exploration of the duct without the need for re-operation.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

With the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) have become the usual procedure for treating common duct stones, since laparoscopic common duct exploration is not yet a widely practised technique (Box 10.4). Moreover, cholecystectomy without cholangiography is commonly performed in the expectation that ERCP and ES will be effective in dealing with unrecognised retained common duct stones at a later date. Such a policy, however, does expose the patient to an additional and often unnecessary procedure. Laparoscopic common duct exploration by whatever route has the advantage for the patient of being able to deal with both gallbladder and CBD stones at the same time.92

There is general agreement that endoscopic removal of bile duct stones is preferable to surgery in postcholecystectomy patients, and in high-risk surgical patients when the gallbladder is still present – that is, patients with severe acute cholangitis and selected patients with acute biliary pancreatitis.93–95 The author believes ERCP becomes an option when transcystic CBD exploration has failed, but should not be considered the first-line management of all CBD stones.

Duct clearance can be expected in 90–95% of patients undergoing successful sphincterotomy, and this results in an overall success rate for endoscopic stone clearance of 80–95%, the highest success rates being recorded as experience increases.93,95,96 Major complications occur in up to 10% of patients, and include haemorrhage, acute pancreatitis, cholangitis and retroduodenal perforation, but the overall procedure-related mortality is less than 1%.93 However, the 30-day mortality can reach 15%, reflecting the severity of the underlying disease. In selected patients with calculi less than 15 mm in diameter, morbidity may be reduced by papillary dilatation rather than sphincterotomy.94 Difficulties in removing CBD stones endoscopically may be due to unfavourable or abnormal anatomy, such as a periampullary diverticulum or previous surgery. Stones larger than 15 mm and those situated intrahepatically or proximal to a biliary stricture may be difficult to remove (Box 10.5). Adjuvant techniques include mechanical lithotripsy, extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy and chemical dissolution.95,97,98 Although successful stone fragmentation has been reported in up to 80% of patients, the major drawback is the need for multiple treatment sessions and at least one subsequent ERCP to extract stone fragments.

The establishment of ERCP in the prelaparoscopic era was based on the avoidance of an open exploration of the CBD, a procedure that was believed to have significant morbidity.99 ERCP was therefore generally reserved for the high-risk surgical patients but open cholecystectomy and exploration of the CBD was reserved for the younger patient. In the laparoscopic era, management strategies vary considerably and are based on local endoscopic and laparoscopic resources and expertise.

ERCP stent insertion

In the 5% or less of situations where extraction of CBD stones is incomplete or impossible, a nasobiliary tube or stent should be inserted to provide biliary decompression and prevent stone impaction of the distal CBD (Fig. 10.8).100 Such manoeuvres may allow improvement of the patient’s clinical condition until complete stone clearance can be achieved by further endoscopic manoeuvres or subsequent surgery. Temporary biliary endoprosthesis placement avoids accidental or intentional dislodgement of the nasobiliary catheter by a confused or uncooperative patient. The stent may become blocked after a few months, but bile drainage often continues around the stent, and the presence of the stent alone may be sufficient to prevent stones from becoming impacted at the lower end of the CBD. In the surgically unfit patient, a change of stent may be required if jaundice recurs. Recurrent episodes of cholangitis may result in secondary biliary cirrhosis in the long term, and careful consideration of the patient’s level of fitness must be made before surgery is totally discounted.

Preoperative ERCP

A randomised study has shown no significant advantage for patients treated by preoperative sphincterotomy as opposed to open cholecystectomy and exploration of CBD alone.101 Despite this, ERCP and ES have become popular practice in the management of CBD stones, with an increased reliance on ERCP and a reluctance among surgeons to perform surgical exploration of the CBD.102

Cholecystectomy should routinely follow clearance of the CBD except in those considered too frail or unfit for general anaesthetic. It can be expected that if the gallbladder is left intact following ERCP and ES, up to 47% of patients will develop at least one recurrent biliary event, with many requiring cholecystectomy.86

Intraoperative ERCP

There have been several reports over the years describing this technique with success but few centres consider this the most appropriate use of resources.103

Postoperative ERCP

If ductal stones are not suspected preoperatively, their presence can be determined at laparoscopic cholecystectomy by IOC. CBD stones identified in this way could be referred for postoperative endoscopic clearance if the surgeon was unable to explore the duct. Such a policy would reduce dramatically the number of ERCPs undertaken by a policy of routine or selective preoperative ERCP. This would leave only a small proportion of patients in whom stones could not be cleared by ERCP, requiring a second operation.104 If the surgeon is trained in laparoscopic exploration of the CBD, ERCP should be reserved for the few patients in whom laparoscopic ductal clearance fails. A recent randomised trial lends some evidence that this approach is safe and represents an effective management plan.88

There is also an argument for leaving small stones (< 5 mm) found intraoperatively. On follow-up for up to 33 months in a small group of patients, 29% in this category developed symptoms, but were safely managed with ERCP.105

Laparoscopic exploration of the CBD versus preoperative or postoperative ERCP

Preoperative ERCP and laparoscopic clearance of the CBD have been shown to be equivalent in overall outcomes.83 However, those patients whose ductal stones were cleared transcystically experienced a far shorter hospital stay.

Postoperative ERCP clearance in a small single-surgeon study showed equivalent overall outcome to laparoscopic CBD clearance.84 However, the number of choledochotomies was small and the retained stone rate high. Placement of biliary stents at the time of operation may improve the success of postoperative ERCP and stone clearance.

With experience, the majority of CBD stones can be treated at the time of surgery provided a flexible approach is employed.85 No single technique will be applicable to the management of all stones. In general, if the stones are few in number, small (< 1 cm) in size, situated in the common duct or distal to cystic duct entry, then transcystic exploration has a high chance of success. If the stone or stones are large and numerous, or if the stones are situated in the common hepatic duct or intrahepatic biliary tree, a choledochotomy and exploration with the larger 5-mm choledochoscope is the preferred option.

• to ligate the cystic duct, complete the cholecystectomy and rely on postoperative ERCP;

If laparoscopic choledochotomy fails, the options include: insertion of a T-tube and subsequent extraction of the retained stones via the T-tube track after 6 weeks; postoperative ERCP and sphincterotomy; or conversion to open exploration CBD. Individual circumstances will dictate which option is the most suitable, although this should be discussed carefully with the patient before a management strategy is implemented.

It has been suggested that preoperative ERCP is the most cost-effective management of patients at high risk for CBD stones.106 There is evidence accumulating, however, that where transcystic clearance is successful this leads to less morbidity and more rapid recovery.83,88 The author believes the most cost-effective approach is laparoscopic cholecystectomy, IOC and transcystic clearance of CBD stones, reserving ERCP for retained stones. Learning the techniques to achieve this seems worthwhile.

In a recent extensive review of the literature, it was concluded that laparoscopic CBD exploration is safe and effective for all patients presenting with gallstones and may be a better way of removing CBD stones than ERCP.107,108

Recurrent or retained CBD stones

Recurrent CBD stones occur in up to 10% of cases. In a retrospective series of 169 patients followed for up to 19 years, recurrences were more common in patients with primary duct stones, large CBD diameter (around 16 mm) and periampullary diverticula. Lowest recurrence rates were found in those patients undergoing choledochoduodenostomy.73

The T-tube is removed, a guidewire is left in situ, and either a steerable catheter or choledochoscope is advanced down the track and into the CBD. With choledochoscopy, the remainder of the technique is identical to that carried out at open operation.109 With the steerable catheter technique, fluoroscopy and further cholangiograms are taken as the stones are retrieved with a stone basket.110

Transhepatic stone retrieval

In a few patients, particularly those who have previously undergone a Pólya gastrectomy, the ampulla will not be readily accessible for ERCP. Access to the common duct can be achieved using a percutaneous transhepatic technique. Over a percutaneously inserted guidewire, a series of dilators are advanced into the biliary tree, so as to develop a transhepatic tract. Following insertion of a sheath, a choledochoscope or steerable catheter can be inserted and stones retrieved.111

Acalculous biliary pain

Given the poor understanding of the mechanisms of pain production in patients with acalculous biliary disease, the outcome for patients following cholecystectomy is uncertain. There is gathering evidence that some patients have abnormal motility of the sphincter of Oddi, in addition to the gallbladder. Some authors have reported improvement in symptoms in as many as 85–95% of patients with acalculous biliary pain after cholecystectomy,112 but it is conceivable that surgery confers a placebo effect. Controversy exists over the use of cholecystokinin (CCK) provocation tests as a means of reproducing symptoms and predicting which patients might benefit from cholecystectomy. In one study, all 26 patients with positive CCK tests showed improvement after removal of the gallbladder,113 whereas 10 of the 16 patients with negative tests were found to have other pathology accounting for their pain. Despite these encouraging results, other investigators have failed to demonstrate differences in outcome in patients with positive CCK tests when compared to those with negative tests.114 Objective criteria on which to base the decision to recommend cholecystectomy in such patients are difficult to define. It is clear, however, that despite the minimally invasive nature of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, there should be no relaxation in the indications for cholecystectomy in patients with acalculous biliary pain.

References

1. Godfrey, P.J., Bates, T., Harrison, M., et al, Gallstones and mortality: a study of all gallstone related deaths in a single health district. Gut 1984; 25:1029–1033. 6479677

2. Hospital In-patient Inquiry Main tables Department of Health and Social Security/Office of Population Census and Surveys. London: HMSO; 1980. [1989].

3. American College of Surgeons. Socio-economic fact book for surgery. Chicago: Socioeconomic Affairs Department, American College of Surgeons; 1988.

4. Motson, R.W. Operative cholangiography. In: Motson R.W., ed. Retained common duct stones. Prevention and treatment. London: Grune & Stratton; 1985:8–9.

5. Neoptolemos, J.P., Hofmann, A.F., Moossa, A.R., Chemical treatment of stones in the biliary tree. Br J Surg 1986; 73:515–524. 3089354

6. Bennion, L.J., Grundy, S.M., Risk factors for the development of cholelithiasis in man. N Engl J Med 1978; 299:1161–1221. 360067

7. Scragg, R.K., McMichael, A.J., Seamark, R.F., Oral contraceptives, pregnancy and endogenous oestrogen in gallstone disease – a case controlled study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984; 288:1795–1799. 6428548

8. Scragg, R.K., McMichael, A.J., Baghurst, P.A., Diet, alcohol and relative weight in gallstone disease: a case controlled study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984; 288:1113–1119. 6424754

9. Richardson, W.S., Surowiec, W.J., Carter, K.M., et al, Gallstone disease in heart transplant recipients. Ann Surg 2003; 237:273–276. 12560786

10. Festi, D., Colecchia, A., Orsini, M., et al, Gallbladder motility and gallstone formation in obese patients following very low calorie diets. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22(6):592–600. 9665682

11. Nakeeb, A., Comuzzie, A.G., Martin, L., et al, Gallstones: genetics versus environment. Ann Surg. 2002;235(6):842–849. 12035041

12. Dowling, R.H., Veysey, M.J., Pereira, S.P., et al, Role of intestinal transit in the pathogenesis of gallbladder stones. Can J Gastroenterol. 1997;11(1):57–64. 9113801

13. Vitek, L., Carey, M.C., New pathophysiologic concepts underlying pathogenesis of pigment gallstones. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2012;36(2):122–129. 21978438

14. Keighley, M.R.B., Micro-organisms in the bile. A preventable cause of sepsis after biliary surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1977; 59:328–334. 879637

15. Glenn, F., Moody, F.G., Acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1961; 113:265–273. 13706025

16. Taylor, T.V., Torrance, B., Rimmer, S., et al, Operative cholangiography: is there a statistical alternative? Am J Surg 1983; 145:640–643. 6342435

17. Wilson, T.G., Hall, J.C., Watts, J.M., Is operative cholangiography always necessary? Br J Surg 1986; 73:637–640. 3742178

18. Prat, F., Meduri, B., Ducot, B., et al, Prediction of common bile duct stones by noninvasive tests. Ann Surg. 1999;229(3):362–368. 10077048

19. Lindsel, D.R.M., Ultrasound imaging of pancreas and biliary tract. Lancet 1990; 335:390–393. 1968124

20. Prat, F., Amouyal, G., Amouyal, P., et al, Prospective controlled study of endoscopic ultrasonography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in patients with suspected common bile duct lithiasis. Lancet. 1996;347(8994):75–79. 8538344 A study making the case for endoscopic ultrasonography as an alternative to ERCP for the detection of common bile duct stones.

21. Norton, S.A., Alderson, D., Endoscopic ultrasonography in the evaluation of idiopathic acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 2000; 87:1650–1655. 11122178

22. Baroll, R.L., Common bile duct stones. Reassessment of criteria for CT diagnosis. Radiology 1987; 162:419–424. 3797655

23. Ichii, H., Takada, M., Kashiwagi, R., et al, Three-dimensional reconstruction of biliary tract using spiral computed tomography for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg 2002; 26:608–611. 12098055

24. Hochwalk, S.N., Dobransky, M., Rofsky, N.M., et al, Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography accurately predicts the presence or absence of choledocholithiasis. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2(6):573–579. 10457316

25. Masui, T., Takehara, Y., Fujiwara, T., et al, MR and CT cholangiography in evaluation of the biliary tract. Acta Radiol. 1998;39(5):557–563. 9755708

26. Liu, T.H., Consorti, E.T., Kawashima, A., et al, Patient evaluation and management with selective use of magnetic resonance cholangiography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography before laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2001;234(1):33–40. 11420481

27. Gracie, W.A., Ransahoff, D.F., The natural history of silent gallstones: the innocent gallstone is not a myth. N Engl J Med 1982; 307:798–800. 7110244

28. McSherry, C.K., Glenn, F., The incidence and causes of death following surgery for non-malignant biliary tract disease. Ann Surg 1980; 191:271–275. 7362293

29. Lagergren, J., Mattsson, F., Cholecystectomy as a risk factor for oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg 2011; 98:1133–1137. 21590760

30. Schmidt, M., Søndenaa, K., Vetrhus, M., et al, A randomized controlled study of uncomplicated gallstone disease with 14-year follow-up showed that operation was the preferred treatment. Dig Surg 2011; 28:270–276. 21757915

31. Iser, J.H., Dowling, R.H., Mok, H.Y.I., et al, Chenodeoxycholic acid treatment of gallstones. N Engl J Med 1975; 293:378–383. 1152936

32. O’Donnell, L.D.J., Heaton, K.W., Recurrence and re-recurrence of gallstones after medical dissolution: a long-term follow-up. Gut 1988; 29:655–658. 3396952

33. Ahmed, R., Freeman, J.V., Ross, B., et al, Long term response to gallstone treatment – problems and surprises. Eur J Surg 2000; 166:447–454. 10890540

34. Sauerbruch, T., Stern, M., Fragmentation of bile duct stones by extracorporeal shockwaves. A new approach to biliary calculi after failure of routine endoscopic measures. Gastroenterology 1989; 96:146–152. 2642439

35. Clavien, P.A., Sanabria, J.R., Mentha, G., et al, Recent results of elective open cholecystectomy in a North American and a European centre – comparison of complications and risk factors. Ann Surg 1992; 216:618–626. 1466614

36. Bredesen, J., Jorgensen, T., Andersen, T.F., et al, Early postoperative mortality following cholecystectomy in the entire female population of Denmark – 1977–1991. World J Surg 1992; 16:530–535. 1589992 Both these papers document the results of open cholecystectomy prior to the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

37. Andren-Sandberg, A., Alinder, A., Bengmark, S., Accidental lesions of the common bile duct at cholecystectomy: pre- and peroperative factors of importance. Ann Surg 1985; 201:328–333. 3977435 Frequently cited study that documents risk factors implicated in injury to the common bile duct during open cholecystectomy.

38. Connor, S., Garden, O.J., Bile duct injury in the era of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2006; 93:158–168. 16432812

39. Bates, T., Ebbs, S.R., Harrison, M., et al, Influence of cholecystectomy on symptoms. Br J Surg 1991; 78:964–967. 1913118

40. MacMahon, A.J., Russell, I.T., Baxter, J.N., et al, Laparoscopic versus minilaparotomy cholecystectomy: a randomised trial. Lancet 1994; 343:135–138. 7904002

41. Majeed, A.W., Troy, G., Nicholl, J.P., et al, Randomised, prospective, single-blind comparison of laparoscopic versus small-incision cholecystectomy. Lancet 1996; 347:989–994. 8606612

42. Ros, A., Gustafsson, L., Krook, H., et al, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus mini-laparotomy cholecystectomy: a prospective, randomised, single-blind study. Ann Surg. 2001;234(6):741–749. 11729380 No evidence to support routine mini-cholecystectomy.

43. Dubois, F., Icard, P., Berthelot, G., et al, Coelioscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg 1990; 211:60–62. 2294845

44. Nathanson, L.K., Shimi, S., Cuschieri, A., Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: the Dundee technique. Br J Surg 1991; 78:155–159. 1826623

45. Gramatica, L., Brasesco, O.E., Mercado, L.A., et al, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed under regional anaesthesia in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Surg Endosc 2002; 16:472–475. 11928031

46. Ghumman, E., Barry, M., Grace, P.A., Management of gallstones in pregnancy. Br J Surg 1997; 84:1646–1650. 9448609

47. Yeh, C.N., Chen, M.F., Jan, Y.Y., Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in 226 cirrhotic patients. Experience of a single centre in Taiwan. Surg Endosc 2002; 16:1583–1587. 12085147

48. Cuschieri, A., Dubois, F., Mouiel, J., et al, The European experience of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am J Surg 1991; 161:385–387. 1825763

49. The Southern Surgeons Club, A prospective analysis of 1518 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. N Engl J Med 1991; 324:1073–1078. 1826143

50. Wilson, P., Leese, T., Morgan, W.P., et al, Elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy for ‘all comers’. Lancet 1991; 338:795–797. 1681169

51. Unger, S.W., Rosenbaum, G., Unger, H.M., et al, A comparison of laparoscopic and open treatment of acute cholecystitis. Surg Endosc 1993; 7:408–411. 8211618

52. Navez, B., Mutter, D., Russier, Y., et al, Safety of laparoscopic approach for acute cholecystitis: retrospective study of 609 cases. World J Surg. 2001;25(10):1352–1356. 11596902

53. Richards, C., Edwards, J., Culver, D., et al, Does using a laparoscopic approach to cholecystectomy decrease the risk of surgical site infection? Ann Surg. 2003;(3):358–362. 12616119

54. Al-Ghnaniem, R., Benjamin, I.S., Patel, A.G., Meta-analysis suggests antibiotic prophylaxis is not warranted in low-risk patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2003; 90:365–366. 12594674

55. Lau, H., Brooks, D.C., Contemporary outcomes of ambulatory laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a major teaching hospital. World J Surg 2002; 26:1117–1121. 12209240

56. Cheah, W.K., Lenzi, J.E., So, B.Y., et al, Randomised trial of needlescopic versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2001; 88:45–47. 11136308

57. Lai, E.C.H., Yang, G.P.C., Tang, C.N., et al, Prospective randomized comparative study of single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus conventional four-port laparoscopic cholestectomy. Am J Surg 2011; 202:254–258. 21871979

58. Richardson, M.C., Bell, G., Fullarton, G.M., The West of Scotland Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Audit Group, Incidence and nature of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an audit of 5913 cases. Br J Surg 1996; 83:1356–1360. 8944450

59. MacFadyen, B.V., Vecchio, R., Ricardo, A.E., et al, Bile duct injury after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 1998; 12:315–321. 9543520

60. Archer, S.B., Brown, D.W., Hunter, J.G., et al, Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of a national survey. Ann Surg. 2001;234(4):549–559. 11573048

61. Way, L.W., Stewart, L., Hunter, J.G., et al, Causes and prevention of laparoscopic bile duct injuries. Analysis of 252 cases from a human factors and cognitive psychology perspective. Ann Surg 2003; 4:460–469. 12677139

62. Keus, F., de Jong, J.A.F., Gooszen, H.G., et al, Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4) CD006231. 17054285

63. Fletcher, D.R., Hobbs, M., Tan, P., et al, Complications of cholecystectomy. Risks of the laparoscopic approach and protective effects of operative cholangiography: a population-based study. Ann Surg. 1999;229(4):449–457. 10203075

64. Flum, D.R., Dellinger, E.P., Cheadle, A., et al, Intraoperative cholangiography and risk of common bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. JAMA 2003; 289:1639–1644. 12672731 Large study on 1.5 million patients demonstrating an increased risk of common bile duct injury when intraoperative cholangiography was not used during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

65. Snow, L.L., Evaluation of operative cholangiography in 2043 patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A case for the selective operative cholangiogram. Surg Endosc 2001; 15:14–20. 11178754

66. John, T.G., Banting, S.W., Pye, S., et al, Preliminary experience with intracorporeal laparoscopic ultrasonography using a sector scanning probe. A prospective comparison with intraoperative cholangiography in the detection of choledocholithiasis. Surg Endosc 1994; 8:1176–1181. 7809800

67. Greig, J.D., John, T.G., Mahadaven, M., et al, Laparoscopic ultrasonography in the evaluation of the biliary tree during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1994;81(8):1202–1206. 7953360

68. Tranter, S.E., Thompson, M.H., Potential of laparoscopic ultrasonography as an alternative to operative cholangiography in the detection of bile duct stones. Br J Surg 2001; 88:65–69. 11136312

69. Tranter, S.E., Thompson, M.H., A prospective single-blinded controlled study comparing laparoscopic ultrasound of the common bile duct with operative cholangiography. Surg Endosc 2003; 17:216–219. 12457223

70. Catheline, J.M., Turner, R., Paries, J., Laparoscopic ultrasonography is a complement to cholangiography for the detection of choledocholithiasis at laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 2002; 89:1235–1239. 12296889

71. Tranter, S.E., Thompson, M.H., Spontaneous passage of bile duct stones: frequency of occurrence and relation to clinical presentation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2003; 85:174–177. 12831489

72. Lygidakis, N.J., A prospective randomised study of recurrent choledocholithiasis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982;155(5):679–684. 7135175

73. Panis, Y., Fagniez, P.L., Brisset, D., et al, Long-term results of choledochoduodenostomy versus choledochojejunostomy for choledocholithiasis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993;177(1):33–37. 8322146 Two studies stressing the need to consider a surgical drainage procedure if ductal stones are thought to represent primary calculi.

74. Uchiyama, K., Onishi, H., Tani, M., et al, Long-term prognosis after treatment of patients with choledocholithiasis. Ann Surg. 2003;238(1):97–102. 12832971

75. Jeyapalan, M., Almeida, J.A., Michaelson, R.L., et al, Laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy: review of a 4-year experience with an uncommon problem. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 2002;12(3):148–153. 12080253

76. Rhodes, M., Nathanson, L., Laparoscopic choledochoduodenostomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1996;6(4):318–321. 8840458

77. Strömberg, C., Nilsson, M., Nationwide study of the treatment of common bile duct stones in Sweden between 1965 and 2009. Br J Surg 2011; 98:1766–1774. 21935910

78. Petelin, J.B., Clinical results of common bile duct exploration. Endosc Surg Allied Technol. 1993;1(3):125–129. 8055310

79. Berci, G., Morgenstern, L., Laparoscopic management of common bile duct stones. A multi-institutional SAGES study. Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons. Surg Endosc 1994; 8:1168–1174. 7809799

80. Rhodes, M., Nathanson, L., O’Rourke, N., et al, Laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct: lessons learned from 129 consecutive cases. Br J Surg 1995; 82:666–668. 7613948

81. Khoo, D., Walsh, C.J., Murphy, C., et al, Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: evolution of a new technique. Br J Surg 1996; 83:341–346. 8665187

82. Martin, I.J., Bailey, I.S., Rhodes, M., et al, Towards T-tube free laparoscopic bile duct exploration: a methodologic evolution during 300 consecutive procedures. Ann Surg. 1998;228(1):29–34. 9671063

83. Cuschieri, A., Lezoche, E., Morino, M., et al, E.A.E.S. multicentre prospective randomised trial comparing two-stage vs. single-stage management of patients with gallstone disease and ductal calculi. Surg Endosc. 1999;13(10):952–957. 10526025

84. Rhodes, M., Sussman, L., Cohen, L., et al, Randomised trial of laparoscopic exploration of common bile duct versus postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for common bile duct stones. Lancet 1998; 351:159–161. 9449869 Two important randomised studies indicating success of laparoscopic bile duct exploration.

85. Buddingh, K.T., Weersma, R.K., Savenije, R.A.J., et al, Lower rate of major bile duct injury and increased intraoperative management of common bile duct stones after implementation of routine intraoperative cholangiography. J Am Coll Surg 2011; 213:267–274. 21459631

86. Boerma, D., Rauws, E.A.J., Keulemans, Y.C.A., et al, Wait-and-see policy of laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile-duct stones: a randomised trial. Lancet 2002; 360:761–765. 12241833

87. Riciardi, R., Islam, S., Canete, J.J., et al, Effectiveness and long-term results of laparoscopic common bile duct exploration. Surg Endosc 2003; 17:19–22. 12399840

88. Nathanson, L.K., O’Rourke, N.A., Martin, I.J., et al, Postoperative ERCP versus laparoscopic choledochotomy for clearance of selected bile duct calculi: a randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2005;242(2):188–192. 16041208

89. Collins, C., Maguire, D., Ireland, A., et al, A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg. 2004;239(1):28–33. 14685097

90. Finnis, D., Rowntree, T., Choledochoscopy in exploration of the common bile duct. Br J Surg 1977; 64:661–664. 589004

91. Williams, J.A., Treacy, P.J., Sidey, P., et al, Primary duct closure versus T-tube drainage following exploration of the common bile duct. Aust N Z J Surg. 1994;64(12):823–826. 7980254

92. Tanaka, M., Bile duct clearance, endoscopic or laparoscopic? J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2002; 9:729–732. 12658407

93. Leese, T., Neoptolemos, J.P., Carr-Locke, D.L., Successes, failures, early complications and their management: results of 394 consecutive patients from a single centre. Br J Surg 1985; 72:215–219. 3872152

94. Ochi, Y., Mukawa, K., Kiyosawa, K., et al, Comparing the treatment outcomes of endoscopic papillary dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for removal of bile duct stones. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14(1):90–96. 10029284

95. Vaira, D., Ainley, C., Williams, S., et al, Endoscopic sphincterotomy in 1000 consecutive patients. Lancet 1989; ii:431–434. 2569609 Three reports supporting use of endoscopic removal of common bile duct stones in high-risk surgical patients.

96. Lambert, M.E., Betts, C.D., Hill, J., et al, Endoscopic sphincterotomy – the whole truth. Br J Surg 1991; 78:473–476. 2032109

97. Webber, J., Ademak, H.E., Riemann, J.F., Extracorporeal piezo-electric lithotripsy for retained bile duct stones. Endoscopy 1992; 24:239–243. 1612036

98. Shaw, M.J., Mackie, R.D., Moore, J.P., et al, Results of a multi-centre trial using a mechanical lithotriptor for the treatment of large bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:730–733. 8480739

99. Leese, T., Neoptolemos, J.P., Baker, A.R., et al, Management of acute cholangitis and the impact of endoscopic sphincterotomy. Br J Surg 1986; 73:988–992. 3790964

100. Leung, J.W.C., Cotton, P.B., Endoscopic nasobiliary catheter drainage in biliary and pancreatic disease. Am J Gastroenterol 1991; 86:389–394. 2012035

101. Neoptolemos, J.P., Carr-Locke, D.L., Fossard, N.P., A prospective randomised study of pre-operative endoscopic sphincterotomy versus surgery alone for common bile duct stones. Br Med J 1987; 294:470–474. 3103731

102. Barwood, N.T., Valinsky, L.J., Hobbs, M., et al, Changing methods of imaging the common bile duct in the laparoscopic cholecystectomy era in Western Australia Implications for surgical practice. Ann Surg. 2002;235(1):41–50. 11753041

103. Tatulli, F., Cuttitta, A., Laparoendoscopic approach to treatment of common bile duct stones. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2000;10(6):315–317. 11132910

104. Ng, T., Amaral, J., Timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the treatment of choledocholithiasis. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech Part A. 1999;9(1):31–37. 10194690

105. Ammori, B.J., Birbas, K., Davides, D., et al, Routine vs ‘on demand’ postoperative ERCP for small bile duct calculi detected at intraoperative cholangiography. Surg Endosc 2000; 14:1123–1126. 11148780

106. Urbach, D.R., Khanjanchee, Y.S., Jobe, B.A., et al, Cost-effective management of common bile duct stones. Surg Endosc 2001; 15:4–13. 11178753

107. Tranter, S.E., Thompson, M.H., Comparison of endoscopic sphincterotomy and laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct. Br J Surg 2002; 89:1495–1504. 12445057

108. Martin, D.J., Vernon, D.R., Toouli, J., Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2) CD003327. 16625577 Similar clearance rates and more procedures with ERCP.

109. Menzies, D., Motson, R.W., Percutaneous flexible choledochoscopy: a simple method for retained common bile duct stone removal. Br J Surg. 1991;78(8):959–960. 1913117

110. Mason, R., Percutaneous extraction of retained gallstones via the T-tube track – British experience of 131 cases. Clin Radiol 1980; 31:587–597. 7471636

111. Nussinson, E., Cairns, S.R., Vaira, D., et al, A 10-year single centre experience of percutaneous and endoscopic extraction of bile duct stones with T-tube in situ. Gut 1991; 32:1040–1043. 1916488

112. Nathan, M.H., Newman, M.A., Murray, D.J., et al, Cholecystokinin cholecystography. Four years evaluation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1970; 110:240–251. 5472657

113. Lennard, T.W.J., Farndon, J.R., Taylor, R.M.R., Acalculous biliary pain: diagnosis and selection for cholecystectomy using the cholecystokinin test for pain reproduction. Br J Surg 1984; 71:368–370. 6372934

114. Sunderland, G.T., Carter, D.C., Clinical application of the cholecystokinin provocation test. Br J Surg 1988; 75:444–449. 3292004