CHAPTER 69 Gallbladder and biliary tree

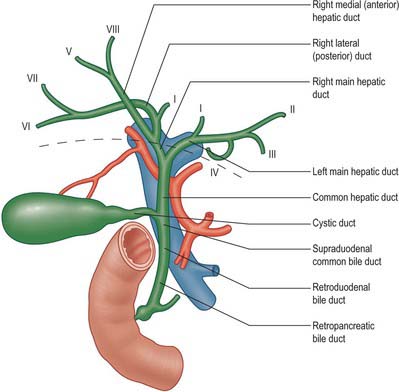

The biliary tree consists of the system of vessels and ducts which collect and deliver bile from the liver parenchyma to the second part of the duodenum. It is conventionally divided into intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary trees. The intrahepatic ducts are formed from the larger bile canaliculi which come together to form segmental ducts. These fuse close to the porta hepatis into right and left hepatic ducts. The extrahepatic biliary tree consists of the right and left hepatic ducts, the common hepatic duct, the cystic duct and gallbladder and the common bile duct (Fig. 69.1).

GALLBLADDER

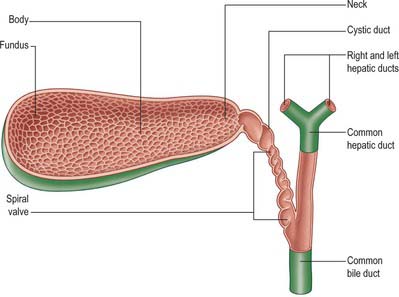

The gallbladder is a flask-shaped, blind-ending diverticulum attached to the common bile duct by the cystic duct. In life, it is grey-blue in colour and usually lies attached to the inferior surface of the right lobe of the liver by connective tissue (Fig. 69.2). In the adult the gallbladder is between 7 and 10 cm long with a capacity of up to 50 ml. It usually lies in a shallow fossa in the liver parenchyma covered by peritoneum continued from the liver surface. This attachment can vary widely. At one extreme the gallbladder may be almost completely buried within the liver surface, having no peritoneal covering (intraparenchymal pattern); at the other extreme it may hang from a short mesentery formed by the two layers of peritoneum separated only by connective tissue and a few small vessels (mesenteric pattern). The gallbladder is described as having a fundus, body and neck. The neck lies at the medial end close to the porta hepatis, and almost always has a short peritoneal-covered attachment to the liver (mesentery); this mesentery usually contains the cystic artery. The mucosa at the medial end of the neck is obliquely ridged, forming a spiral groove continuous with the spiral valve of the cystic duct. At its lateral end the neck widens out to form the body of the gallbladder and this widening is often referred to in clinical practice as ‘Hartmann’s pouch’. The neck lies anterior to the second part of the duodenum.

INTRAHEPATIC BILIARY TREE

SEGMENTAL AND SECTORAL DUCTS

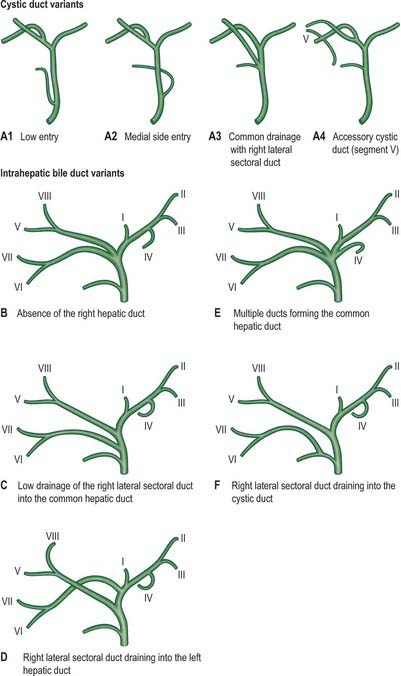

The segmental ducts of the left liver have a relatively constant pattern, although several segmental ducts may drain each particular segment. The left hepatic duct is formed by the union of segment II and III ducts behind the umbilical portion of the left portal vein (Fig. 69.1). The segment IV duct is more variable, but usually drains into the left hepatic duct. The right hepatic duct is formed by the union of the right medial (anterior) and lateral (posterior) sectoral ducts. These sectoral ducts in turn are formed by the segmental ducts: VII and VI from the lateral, and VIII and V from the medial duct. The right lateral sectoral duct is often identified on a cholangiogram as curving around the right medial duct before joining the medial side of the medial sectoral duct: this is often described as Hjortsjo’s crook, and has surgical importance for liver resections. The right hepatic duct and its branches are subject to more variations than the left ductal system, and these variations have been classified by Blumgart into six main types (Table 69.1).

Table 69.1 Variations of the right hepatic duct and its branches

| Type | Percentage of population | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A | 55 | Anatomy is normal. |

| B | 15 | There is no right hepatic duct and the common hepatic duct is formed by the right anterior, right posterior and left hepatic ducts as a trifurcation. |

| C | 20 | There is a low drainage of one the right sectoral ducts into the common hepatic duct. |

| D | 5 | One of the right sectoral ducts joins the left hepatic duct. |

| E | 5 | The common hepatic duct is formed by the union of two or more ducts from either lobe. |

| F | 5 | The right posterior sectoral duct drains into the cystic duct. |

EXTRAHEPATIC BILIARY TREE

CYSTIC DUCT

The cystic duct drains the gallbladder into the common bile duct. It is between 3 and 4 cm long, passes posteriorly to the left from the neck of the gallbladder, and joins the common hepatic duct to form the common bile duct. It almost always runs parallel to, and is adherent to, the common hepatic duct for a short distance before joining it. The junction usually occurs near the porta hepatis but may be lower down in the free edge of the lesser omentum. The cystic duct may have several important variations in its anatomy (Fig. 69.3). Rarely, the cystic duct lies along the right edge of the lesser omentum all the way down to the level of the duodenum before the junction is formed, but in these cases the cystic and common bile ducts are usually closely adherent. The cystic duct occasionally drains into the right hepatic duct, in which case it may be elongated, lie anterior or posterior to the common hepatic duct, and join the right hepatic duct on its left border. Rarely, the duct is double or even absent, in which case the gallbladder drains directly into the common bile duct. One or more accessory hepatic ducts occasionally emerge from segment V of the liver and join either the right hepatic duct, the common hepatic duct, the common bile duct, the cystic duct, or the gallbladder directly. These variations in cystic duct anatomy are of considerable importance during surgical excision of the gallbladder. Ligation or clip occlusion of the cystic duct must be performed at an adequate distance from the common bile duct to prevent angulation or damage to it. Accessory ducts must not be confused with the right hepatic or common hepatic ducts.

COMMON BILE DUCT

The common bile duct is formed near the porta hepatis, by the junction of the cystic and common hepatic ducts (Figs 69.4 and 69.5), and is usually between 6 and 8 cm long. Its diameter tends to increase somewhat with age but is usually around 6 mm in adults. It descends posteriorly and slightly to the left, anterior to the epiploic foramen, in the right border of the lesser omentum, where it lies anterior and to the right of the portal vein and to the right of the hepatic artery. It passes behind the first part of the duodenum with the gastroduodenal artery on its left, and then runs in a groove on the superolateral part of the posterior surface of the head of the pancreas. The duct lies anterior to the inferior vena cava and is sometimes embedded in the pancreatic tissue. It may lie close to the medial wall of the second part of the duodenum or as much as 2 cm from it: even when it is embedded in the pancreas, a groove in the gland marking its position can be palpated behind the second part of the duodenum.

Calot’s triangle

The near triangular space formed between the cystic duct, the common hepatic duct and the inferior surface of segment V of the liver (Suzuki et al 2000), is commonly referred to as Calot’s triangle. It is enclosed by the double layer of peritoneum which forms the short mesentery of the cystic duct. Since the two layers are not closely opposed, there is an appreciable amount of loose connective tissue within the triangle. It is perhaps better described as a pyramidal ‘space’ with one apex lying at the junction of the cystic duct and fundus of the gallbladder, one at the porta hepatis, and two closer apices at the attachments of the gallbladder to the liver bed. The base of the triangle thus lies on the inferior surface of the liver. This space usually contains the cystic artery as it approaches the gallbladder, the cystic lymph node and lymphatics from the gallbladder, one or two small cystic veins, the autonomic nerves running to the gallbladder, and some loose adipose tissue. It may contain any accessory ducts which drain into the gallbladder from the liver. Appreciation of the variations in ductal and arterial anatomy as they relate to the triangle are of considerable importance during excision of the gallbladder in order to avoid mistakenly ligating the common hepatic or common bile duct.

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

Cystic artery

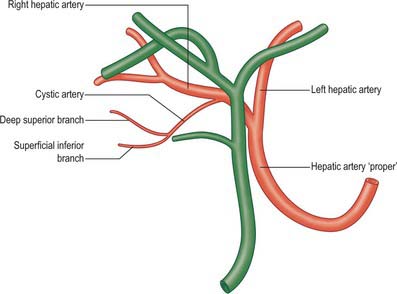

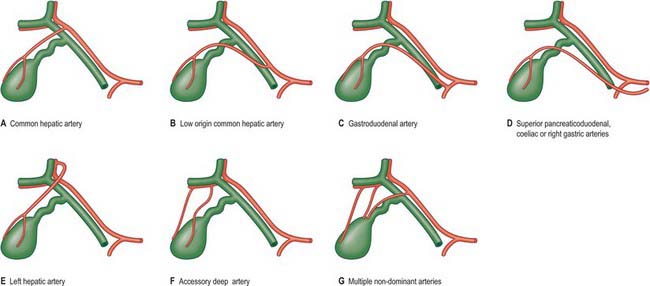

The cystic artery usually arises from the right hepatic artery (Fig. 69.6). It usually passes posterior to the common hepatic duct and anterior to the cystic duct to reach the superior aspect of the neck of the gallbladder and divides into superficial and deep branches. The superficial branch ramifies on the inferior aspect of the body of the gallbladder, the deep branch on the superior aspect. These arteries anastomose over the surface of the body and fundus. The origin of the cystic artery frequently varies (Fig. 69.7). The most common variant is an origin from the common hepatic artery (occasionally low down), sometimes from the left hepatic or gastroduodenal artery, and rarely from the superior pancreaticoduodenal, coeliac, right gastric or superior mesenteric arteries. In these cases, it crosses anterior (or less commonly posterior) to the common bile duct or common hepatic duct to reach the gallbladder. An accessory cystic artery may arise from the common hepatic artery or one of its branches and the cystic artery often bifurcates close to its origin, giving rise to two vessels which approach the gallbladder. Multiple fine arterial branches may arise from the parenchyma of segments IV or V of the liver and contribute to the supply of the body, particularly when the gallbladder is substantially intrahepatic. This makes the gallbladder relatively resistant to necrosis during inflammation which otherwise occludes the cystic artery.

INNERVATION

The gallbladder and the extrahepatic biliary tree are innervated by branches from the hepatic plexus. The retroduodenal part of the common bile duct and the smooth muscle of the hepatopancreatic ampulla are also innervated by twigs from the pyloric branches of the vagi.

MICROSTRUCTURE

GALLBLADDER

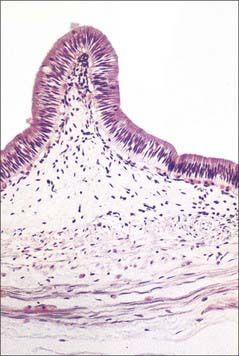

The fundus of the gallbladder is completely covered by a serosa, and the inferior surfaces and sides of the body and neck of the gallbladder are usually covered by a serosa. If the gallbladder possesses a mesentery the serosa extends around the sides of the body and neck onto the superior surface and continues into the serosa of the mesentery, whereas the serosa is limited to the inferior surfaces only if the gallbladder is intrahepatic. Beneath the serosa is subserous loose connective and adipose peritoneal tissue. The gallbladder wall microstructure generally resembles that of the small intestine. The mucosa is yellowish-brown and elevated into minute rugae with a honeycomb appearance (Fig. 69.2). In section, projections of the mucosa into the gallbladder lumen resemble intestinal villi, but they are not fixed structures and the surface flattens as the gallbladder fills with bile. The epithelium is a single layer of columnar cells with apical microvilli; basally, the spaces between epithelial cells are dilated (Fig. 69.8). Many capillaries lie beneath the basement membrane. The epithelial cells actively absorb water and solutes from the bile and concentrate it up to ten-fold. There are no goblet cells in the epithelium. The thin fibromuscular layer is composed of fibrous tissue mixed with smooth muscle cells arranged loosely in longitudinal, circular and oblique bundles.

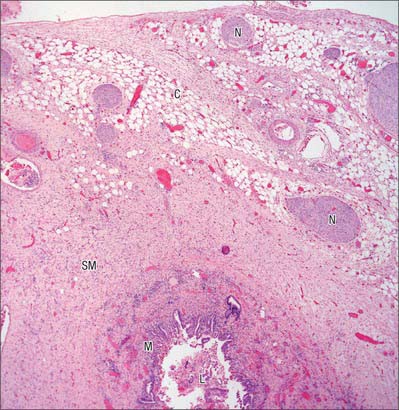

BILE DUCTS

The walls of the large biliary ducts consist of external fibrous and internal mucosal layers (Fig. 69.9). The outer layer is fibrous connective tissue containing a variable amount of longitudinal, oblique and circular smooth muscle cells. The mucosa is continuous with that in the hepatic ducts, gallbladder and duodenum. The epithelium is columnar and there are numerous tubuloalveolar mucous glands in the duct walls.