Gait

BACKGROUND

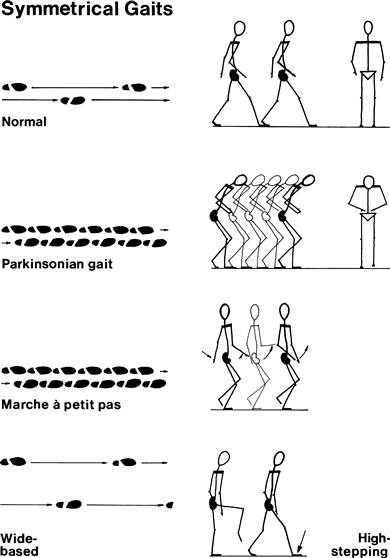

Always examine the patient’s gait. It is a coordinated action requiring integration of sensory and motor functions. The gait may be the only abnormality on examination, or it may lead you to seek appropriate clinical associations on the rest of the examination. The most commonly seen are: hemiplegic, parkinsonian, marche à petits pas, ataxic and unsteady gaits.

Romberg’s test is conveniently performed after examining the gait. This is a simple test primarily of joint position sense.

WHAT TO DO AND WHAT YOU FIND

Ask the patient to walk.

Is the gait symmetrical?

(Gaits can usually be divided into symmetrical and asymmetrical even though the symmetry is not perfect.)

If symmetrical

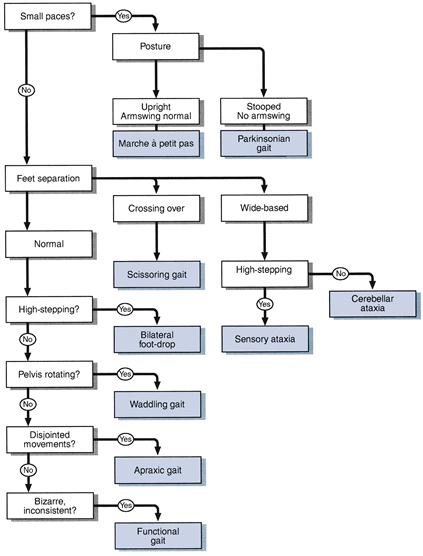

Look at the size of paces:

If small paces:

Look at the posture and arm–swing:

If normal paces:

Look at the lateral distance between the feet:

Look at the knees:

Look at the pelvis and shoulders:

Look at the whole movement:

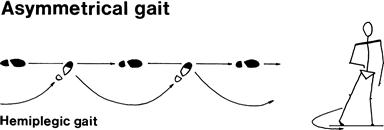

If asymmetrical

Is the patient in pain?

Look for a bony deformity:

Does one leg swing out to the side?

Look at the knee heights:

FURTHER TESTS

Ask the patient to walk as if on a tight-rope (demonstrate).

Ask the patient to walk on his heels (demonstrate).

Ask the patient to walk on his toes (demonstrate).

WHAT IT MEANS

• Hemiplegic: unilateral upper motor neurone lesion. Common causes: stroke, multiple sclerosis.

• Functional gait: variable, may be inconsistent with rest of examination, worse when watched. May be mistaken for the gait in chorea (especially Huntington’s disease), which is shuffling, twitching and spasmodic and has associated findings on examination (see Chapter 24).

Non-neurological gaits

Romberg’s test

What to do

Ask the patient to stand with his feet together.

Tell the patient you are ready to catch him if he falls (make sure you are).

If not:

Ask the patient to close his eyes.