14

Gait

Thomas W.. Kernozek and John D.. Willson

1. Define and describe basic components of the gait cycle.

2. Discuss the two phases of gait.

3. Identify and describe each component of the two phases of gait.

4. Define and describe common gait deviations.

5. Define and instruct appropriate gait patterns.

6. Outline and describe terms used to define weight-bearing status during gait.

7. Identify and discuss the appropriate use of assistive devices.

GAIT CYCLE TERMINOLOGY AND PHASES OF GAIT

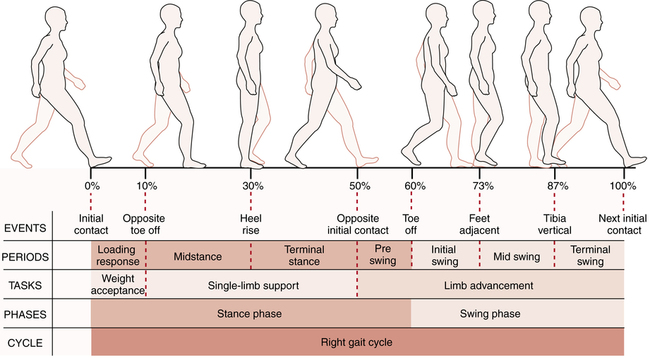

The definition of the gait cycle is based on a reference extremity (for example, the right foot) from a defined event such as heel contact until the next occurrence of that event (contact with the heel of that same foot). The gait cycle is often based on 100% and can be further broken down into the stance phase and the swing phase (Fig. 14-1). The stance phase is defined as the portion of the gait cycle where the foot is in contact with the ground whereas the swing phase is the portion where the foot is off the ground. A step is defined as contact on one foot until contact with the other (right to left or left to right). A stride is defined as contact with the one foot until contact with the same foot (right to right or left to left). The stance phase of the gait cycle is typically about 60% of the gait cycle, whereas the swing phase is about 40% (see Fig. 14-1). The reason why the stance and swing phases are not 50% is due to the relatively short period of double support (10%) within the gait cycle. This small portion of support phase is the period where the weight is transferred from one limb to the other.

The stance phase has been described as having two basic functions: weight acceptance and single limb support; whereas the swing phase has one primary function: limb advancement.16 Figure 14-1 depicts the phases within the stance and swing phases of the gait cycle. Contact with the floor is often made with the heel (often called heel contact or initial contact). Perry16 has described the first 15% of the gait cycle portion as when the foot functions as a heel rocker or first rocker. During this part of the gait cycle, impact forces tend to be large at 1 to 1.5 times body weight, depending on the speed of locomotion. Once the foot becomes flat on the ground the tibia advances forward over the stance foot. Perry16 has described this as the ankle rocker or second rocker. This phase of the gait cycle is also called midstance phase. The terminal stance phase begins when the heel is raised off the ground (about 40% of the stance phase) until the opposite foot makes ground contact. The final phase of stance phase of the gait cycle is the pre-swing phase, which begins with heel strike of the contralateral limb and ends with toe off. When the heel is lifted from the floor (heel off), this can also be described as the toe rocker or third rocker.

CHARACTERISTICS OF NORMAL GAIT

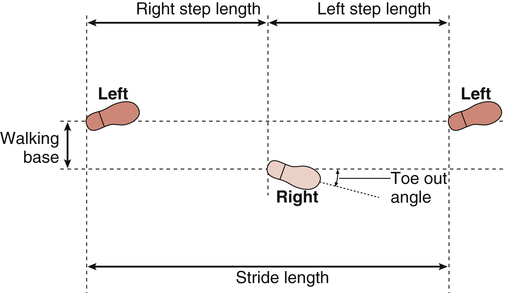

Many factors can influence gait, such as age, pain, strength, range of motion (ROM), walking speed, and fitness level. The extent of the influence of such factors can be quantified by taking simple measurements to characterize and assess a person’s walking performance with a tape measure, goniometer, and stop watch. The measures are stride or step length, step width (walking base), foot progression angle, walking speed, and cadence. Typical stride length reported from the literature has a range of 1.33 to 1.63 m in healthy individuals.4,5,7,9–12,15,18 Males generally have a greater step length than females. Step width or the horizontal distance between feet while walking has a range of 0.61 to 9.0 cm.11,12,17,20 Foot progression angle or angle of toe out has been reported to range between 5.1° and 6.8°. Various definitions for foot placement can be seen in Figure 14-2. The average typical walking speed is 1.49 m/sec for men and 1.40 m/sec for women, ranging between 3 to 4 miles per hour for both genders.2–4,14,18,21 Average walking speed can be measured over a specific distance with a stop watch. Speed can be calculated by taking the distance over the elapsed time taken to walk the prescribed distance. Walking speed is based on cadence (number of steps per minute) and step length. Average cadence has a range of 107 to 125 steps per minute.2–4,14,18,21 To increase walking speed, one can increase cadence or step length. Self selected walking speed is typically slower for women than in men. With the slower gait speed there appears to be a shorter step length and faster cadence for women than men. Keep in mind that all measurements of gait are largely dependent on walking speed.

Normal gait is not entirely symmetrical.18 Small asymmetries in gait are often considered typical. With slower walking speeds, greater amounts of asymmetry have been observed in healthy individuals with normal gait. Thus one must be able to identify if these subtleties in normal gait have clinical relevance.

Motions of the Foot, Ankle, Knee, Hip, and Pelvis

Foot

There are several joints within the foot, with some motion occurring at each of the joints during gait. However, most of the required motion at the foot is from the first metatarsophalangeal joint. At the instant of heel off during the terminal stance phase of gait, the first metatarsophalangeal joint typically hyperextends 45° to 55° as the ankle actively plantarflexes. The first metatarsophalangeal joint then returns to nearly 0° during the remainder of the gait cycle. A limitation in this passive hyperextension may cause compensations in other joints in the chain.19

Ankle

At ground contact, the ankle is primarily in a neutral position (0°, at a right angle to the tibia, neither plantarflexed nor dorsiflexed). After contact, the ankle plantarflexes about 5° so that the foot becomes flat on the ground.16 This motion is controlled eccentrically by the ankle dorsiflexor muscles. Next, the tibia rotates over the stance foot resulting in maximum ankle dorsiflexion. This motion is generally controlled eccentrically by the ankle plantarflexor muscles. During the pre-swing phase of gait, the ankle plantarflexes to propel the person forward. An inadequate amount of plantarflexion may be due to a lack of ankle power, resulting in a reduction in step length during gait. During swing, the ankle must dorsiflex to allow for foot clearance as that leg steps forward for ground contact.

Knee

The knee is close to full extension at ground contact. The knee flexes 10° to 15° as the foot becomes flat on the ground during the initial 15% of the gait cycle. Knee flexion facilitates the absorption of forces during impact as the quadriceps muscles function eccentrically. After foot flat, the knee extends until about 40% of the gait cycle. As the ankle plantarflexes during terminal stance phase, the knee flexes to about 35° at toe off. Knee flexion during this phase reduces the overall length of the limb allowing for adequate foot ground clearance. The knee continues to flex to its maximum at about 60° during mid swing. Later in mid and terminal swing, the knee extends to nearly full extension in preparation for ground contact.16 The knee motion reported during gait in the frontal plane is minimal (within 10° of abduction and adduction during the entire gait cycle) and appears to be quite variable.1,3,8 A small amount of medial rotation of the knee that occurs during early stance and appears to be linked with foot pronation has been reported.8 During midstance and throughout the swing phase the knee appears to laterally rotate back to neutral. Rearfoot pronation is accompanied by tibial medial rotation with knee flexion. This is thought to be important for shock absorption occurring with foot impact with the ground. Tibial lateral rotation occurs later in stance with foot supination and is accompanied by knee extension.

Hip

The hip is flexed to about 30° at ground contact. This is typically the maximum amount of hip flexion observed during normal gait. After this the hip extends to a hyperextension angle of about 10° at about 50% of the gait cycle. Hip flexion is started at pre-swing and continues until nearly ground contact.16

Pelvis

There is a small amount of pelvic motion apparent during the gait cycle. During the gait cycle, the pelvis goes through a symmetrical pattern of excursion twice. In general, the pelvis tilts anterior and the pelvis on the swing leg rotates forward whenever either hip extends. The pelvis also has a considerable amount of oscillating motion in the frontal and transverse planes (up to 10° of total motion). During the first 10% to 15% of the gait cycle the pelvis rotates and laterally tilts toward the swing leg contributing to hip adduction on the stance leg. From about 20% to 60% of the gait cycle, the pelvis rotates and tilts away from the swing leg contributing to hip abduction.16

Joint Motion and Energy Expenditure

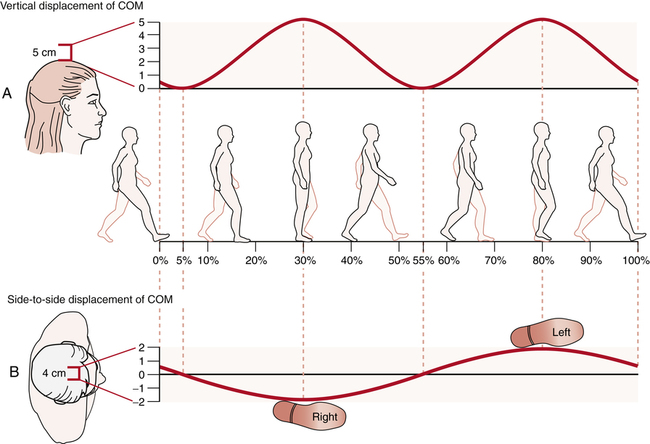

Coordinated lower extremity movement patterns are thought to minimize the vertical oscillation of the body center of mass (COM). The body COM is nearly at the height of a person’s navel and is in the center of the body anterior to the sacrum. Movement of the COM oscillates up and down and from side to side during normal gait (Fig. 14-3). Vertical oscillation of the COM has been related to energy expenditure. Greater energy expenditure is thought to be related to greater oscillation of the body COM. In general, the COM oscillates nearly 5 cm in the vertical direction and horizontally toward the stance limb.6 The COM is typically highest during midstance and lowest during double support phases of gait. Lower extremity gait deviations may result in excessive COM motion, resulting in greater fatigue due to the higher metabolic cost.

Muscle Activation

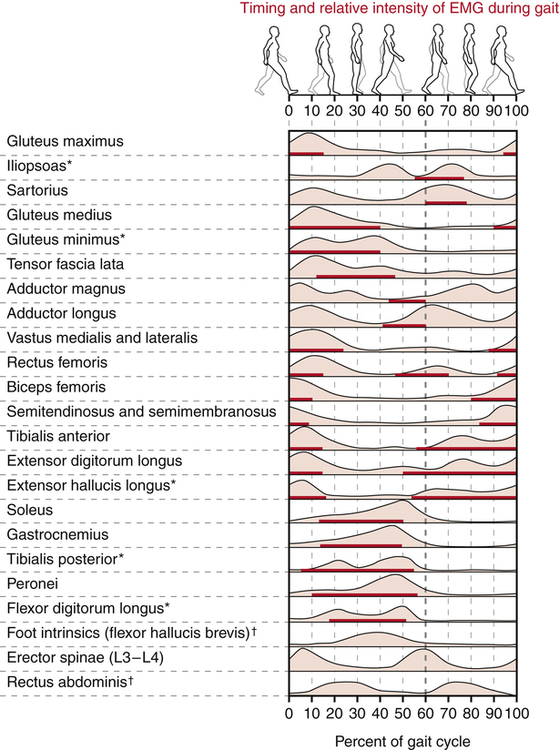

Timing of muscle activation appears to be critical; generally occurring in short bursts during gait (Fig. 14-4). Much of the muscle action within the gait cycle is eccentric. Eccentric forces by the muscles are used control the rate of joint motion.

Foot and Ankle

The tibialis anterior is active eccentrically at heel contact to control the rate of ankle plantar flexion until the foot is flat on the ground. A second period of activity by the tibialis anterior is during early swing phase when it dorsiflexes the ankle to allow for foot clearance. The extensor digitorum and extensor hallucis longus have a similar role in helping control the rate of plantar flexion during the loading response. They may also be activated during the late mid-swing and terminal swing for propulsion in combination with the ankle plantar flexors. The ankle plantarflexors (gastrocnemius and soleus) are active most of the stance phase; eccentrically during the first 10% to 40%, when they control the rate for tibial advancement over the foot, to a high burst of concentric activity at pre-swing (at heel off) until inactivity at toe off.13 The tibialis posterior is primarily active between 5% and 35% of the gait cycle and is thought to limit excessive foot pronation. Later in stance, the tibialis anterior and posterior function concentrically to help supinate the foot to create a rigid lever for effective push off by the ankle plantarflexors.19

Knee

During terminal swing the quadriceps muscle group begins to become activated in preparation for weight acceptance during stance. At the instant of heel contact, the quadriceps is highly active eccentrically to control the rate of knee flexion and absorb impact forces during the loading response phase. Later during midstance while in single limb support, the quadriceps act concentrically to extend the knee. During pre-swing, there may be some quadriceps activity to help flex the hip. The hamstrings are most active near the instant of heel contact and through approximately the first 10% of the stance phase. Before heel contact, the hamstrings slow the rate of knee extension, and early in stance, assist with hip extension and enhance knee stability with coactivation with the quadriceps. Minimal activation of the hamstrings is necessary during pre-swing and swing.13,16,19

Hip

The gluteus maximus is active during terminal swing to slow the rate of hip flexion and to prepare for weight acceptance during stance. This muscle becomes most active at the instant of heel contact for hip extension with assistance from the hamstrings and to prevent trunk flexion. The gluteus maximus remains active during the first 30% of the gait cycle.16 The iliacus and psoas muscles are active eccentrically during toe off to slow down the rate of hip extension, and then are concentrically active to flex the hip during pre-swing. These hip flexors are active only during the first 50% of swing and are partially assisted by the quadriceps for limb advancement and foot clearance. The hip abductors (gluteus medius, gluteus minimis, and tensor fascia lata) help control pelvis motion in the frontal plane during single leg stance.19 The gluteus medius is also active in terminal swing in preparation for heel contact. It is assisted by the gluteus minimus during the first 40% of the gait cycle to control pelvis tilt toward the swing limb during stance and may control the alignment of the femur in the frontal plane. The hip adductors and rotators are also active during stance. The hip rotators’ role during gait may be important to enable control of the motion between the pelvis and femur during stance.13

GAIT ABNORMALITIES

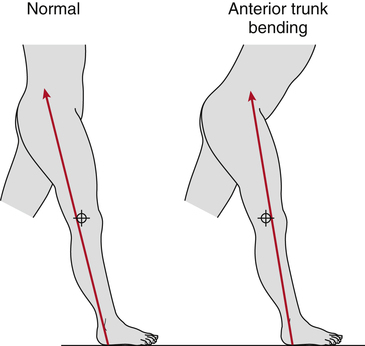

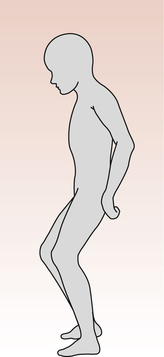

Anterior Trunk Lean

Anterior trunk lean is most commonly observed during the stance phase of gait. However, timing of the anterior trunk lean may vary according to the impairment causing this gait abnormality. Anterior trunk lean during early stance is often a compensation for quadriceps weakness. Shortly after heel strike, the magnitude and direction of the reaction force from the ground is posterior to the knee joint, which tends to produce knee flexion under the eccentric control of the knee extensors. If the knee extensors cannot generate enough force to resist knee flexion, a person may lean forward to move the ground reaction force anterior to the knee joint (Fig. 14-5). Moving the ground reaction force anterior to the knee joint changes the effect of the ground reaction force to one that tends to cause knee extension rather than knee flexion, therefore diminishing the need for knee extension strength to resist knee flexion. Quadriceps weakness is a common consequence of poliomyelitis. Therefore this compensation is a common gait deviation among such individuals.

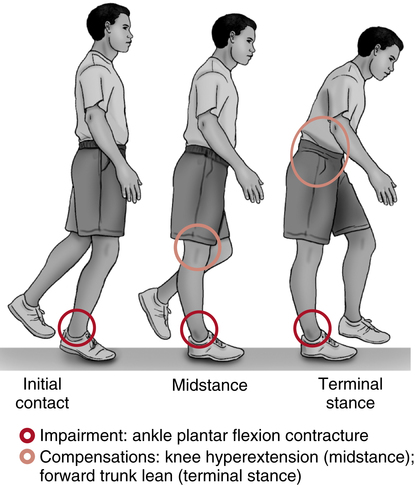

Anterior trunk lean during midstance or terminal stance is often a compensation for decreased ankle dorsiflexion range of motion. In order to continue to ambulate forward, the ankle typically dorsiflexes before initial contact of the contralateral leg to allow the person’s COM to pass anterior to the stance leg base of support. Among individuals with ankle plantarflexor spasticity, a plantarflexor contracture, or pes equinus deformity, the ankle may not permit sufficient dorsiflexion at this stage of the gait cycle and the person may need to lean the trunk forward to move their COM anterior to the foot (Fig. 14-6).

Excessive Ankle Plantarflexion

Increased ankle plantarflexion is frequently observed in both the stance and swing phase of the gait cycle. Increased ankle plantarflexion during and after midstance of the stance leg is commonly referred to as vaulting (Fig. 14-7). This is frequently a compensatory mechanism intended to increase ground clearance for the swing leg and is common among individuals with an impairment that prevents shortening of the swing leg during the swing phase, such as an ankle plantarflexion contracture, ankle dorsiflexor weakness, knee or hip extensor spasticity, or hip flexor weakness. Ankle plantarflexion of the stance leg may also be an indication of decreased ankle dorsiflexion ROM, particularly if the person demonstrates heel rise very shortly after contralateral toe off (early in midstance). In either case, the effect is a characteristic bouncing appearance, indicative of large vertical oscillations of the person’s COM.

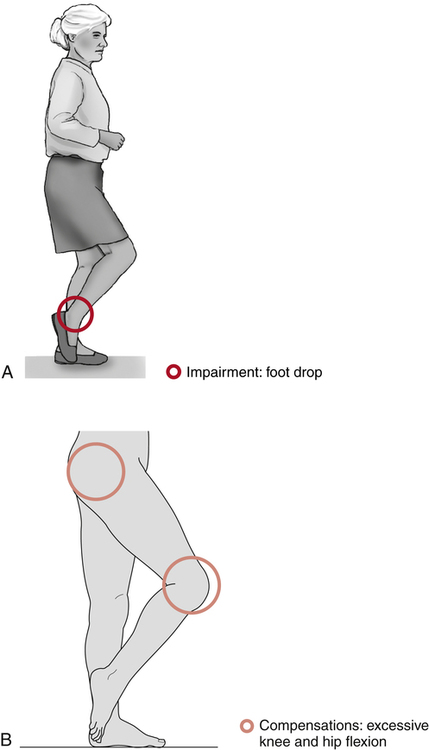

Increased ankle plantarflexion may also be observed in the swing phase of the gait cycle. This gait deviation is frequently the result of injury to the common fibular nerve, weakness of the ankle dorsiflexors, or spasticity or contracture of the ankle plantarflexors (Fig. 14-8, A). Compensations for increased swing phase ankle plantarflexion are typically necessary to avoid tripping due to toe drag during contralateral leg stance phase. These compensations often include vaulting on the stance leg, increased hip or knee flexion of the swing leg (steppage gait) (Fig. 14-8, B), or hip circumduction of the swing leg (described later). A combination of these compensations may also be used in order to increase ground clearance during the swing phase.

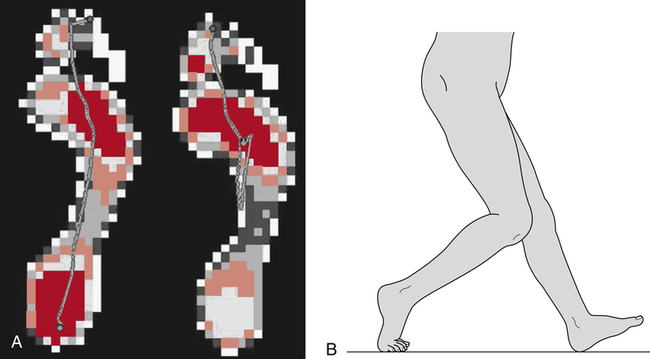

Increased Knee Flexion

Excessive knee flexion is most noticeable during either the loading response or terminal stance phase of the gait cycle, when the knee would normally be nearly fully extended. Increased knee flexion at initial contact will almost certainly be accompanied by initial contact with the midfoot or forefoot rather than the heel. As the remainder of the foot comes in contact with the ground, the center of pressure first moves posteriorly and finally anteriorly during stance rather than the typical posterior to anterior progression (Fig. 14-9, A). One consequence of this is that much of the forward momentum of the COM may be lost during early stance, minimizing the gait economy normally preserved by the foot and ankle rockers. Increased knee flexion during stance phase may be the consequence of a number of impairments including a knee flexion contracture, knee pain or knee joint effusion, or a hip flexion contracture (Fig. 14-9, B).

Increased knee flexion and hip flexion during gait is referred to as crouch gait and is commonly observed among individuals with spastic diplegia as a consequence of cerebral palsy (Fig. 14-10). Among such individuals, increased knee flexion may be due to spasticity of the hamstrings, hip flexors, or both. Careful gait and clinical analysis is required in order to develop the best course of surgical or conservative treatment for these patients.

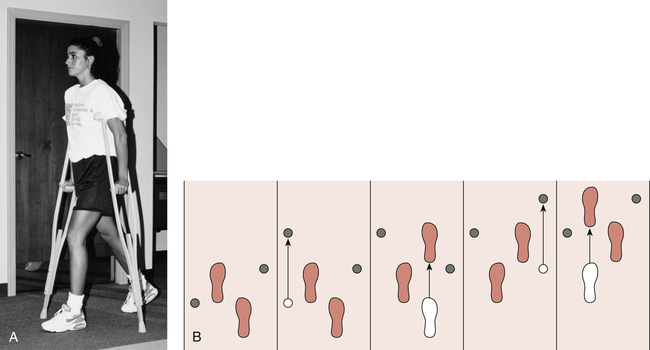

GAIT PATTERN INSTRUCTION

A four-point gait pattern is describe as advancing the crutch opposite the uninvolved limb first, followed by the involved limb, then advancing the crutch toward the uninvolved limb, then finally advancing the uninvolved limb (Fig. 14-11). If the injured limb is the left leg, the four-point gait pattern looks like this:

< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mml" />

The four-point gait pattern attempts to duplicate the normal reciprocal motion that occurs between the upper extremities and the lower limbs during normal gait.

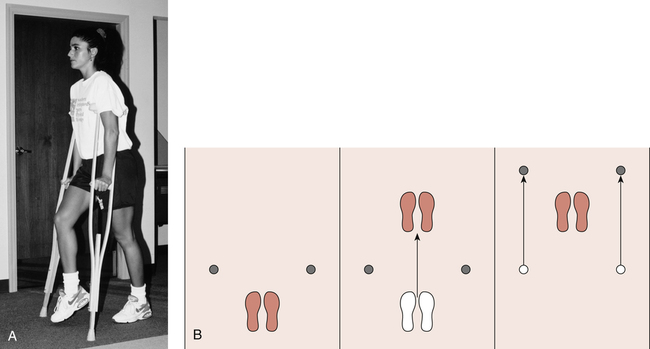

A three-point gait pattern is commonly taught using bilateral axillary crutches (Fig. 14-12). The sequence of events begins by advancing both crutches and the involved limb first followed by the uninvolved.

Selection of Assistive Devices

GLOSSARY

Antalgic gait A general term used to describe a gait pattern accompanied by pain.

Stance phase The portion of the gait cycle during which the foot is in contact with the ground.

Step Contact on one foot until contact with the other (right to left or left to right).

Stride Contact with the one foot until contact with the same foot (right to right or left to left).

Swing phase The portion of the gait cycle during which the foot is off the ground.

Trendelenburg gait Lateral trunk bending as a compensation for ipsilateral hip abductor weakness.

Trendelenburg sign A term used to refer to contralateral pelvic drop.

Vaulting Increased ankle plantarflexion during and after midstance of the stance leg.