Gait

What is gait?

Gait is a highly energy efficient method of locomotion necessary for most daily activities. It involves rhythmical, reciprocal movements of the lower limbs and in terms of biomechanics reflects a destabilizing phase followed by a stabilizing phase (Magee 2006). Commonly, the gait cycle is described in terms of a stance phase (approximately 60% of time) and a swing phase (approximately 40%). The tasks involved in gait include: progression within space but also the achievement of a stable alternating one leg stand and postural stability to maintain an upright stance during all phases. Although for the majority of time gait is automatic, requiring no conscious thought, it actually comprises complex patterns of movement involving the whole body. The rhythmic, repetitive components of gait are thought to be initiated and controlled by central pattern generators within the spinal cord (S2.13). However, when changes in the internal and external environment occur, higher level centres are required to integrate and coordinate the motor response. Therefore, if the central nervous system is damaged the functional ability of a patient to walk is likely to be impaired.

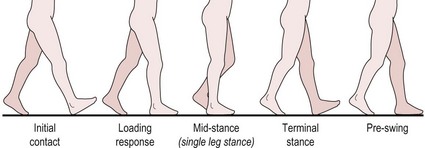

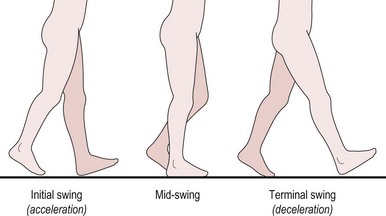

The normal gait cycle is defined as the sequence of motions between two consecutive contacts of the same foot, e.g. heel strike of the left foot to heel strike of the left foot. Stance phase involves heel strike to toe off of the same lower limb (LL), while swing phase includes an initial acceleration phase through to a terminal deceleration phase. An understanding of the normal gait cycle (Figs 19.1, 19.2) and its biomechanics in terms of joint angles and muscle activity is vital to completing a sound assessment, with insufficient knowledge leading to incorrect analysis. A detailed description of normal gait is beyond the scope of this text, however a brief overview of the mechanics of the lower limb is noted below. It should be stressed that all the elements described are integrated in real-time during gait and the therapist should not forget to consider the head/neck, trunk and upper limbs, which are integral in efficient gait.

Stance phase (Fig. 19.1)

Ankle: Dorsiflexion for heel strike, eccentric control of dorsiflexion to gain flat foot, dorsiflexion to achieve mid-stance and plantarflexion for push off

Knee: Slight knee flexion at heel strike (acting as a shock absorber), full extension at mid-stance and slight flexion in preparation for swing phase

Hip: Flexion at heel strike followed by extension and adduction to gain mid-stance and weight transfer. Full hip extension at the end of stance phase just prior to push off

Swing phase (Fig. 19.2)

Ankle: Dorsiflexion at toe off and maintained in preparation for heel strike

Knee: Flexion to shorten the lower limb for ground clearance during swing. Knee extension in preparation for heel strike

Hip: Flexion to initiate acceleration of lower limb at toe off in swing and eccentric control of flexion to decelerate in preparation for heel strike

Pelvis: Slight drop and rotation forward on swing lower limb side at toe off.

Why do I need to assess gait?

Gait dysfunction is common in neurologically impaired patients and can occur from a myriad of different signs and symptoms associated with the pathology. The factors influencing gait may be a direct result of the pathology such as changes in muscle tone, sensation or cognitive and perceptual deficits or due to secondary disuse and inactivity. For example, muscle weakness, alteration of soft tissue extensibility, reduced exercise tolerance or reduced confidence. (For more detail on how specific impairments affect gait, the reader is referred to Chapter 14 in Shumway-Cook and Woollacott 2007).

How do I do gait analysis?

Observation

Patient

Initially the therapist needs to establish how the patient chooses to move without any intervention.

Therapist

1. Sufficient assistance must be given during the assessment to ensure the safety of the patient.

2. The therapist should observe the gait from all directions (front, behind and side) paying attention to each of the main body segments, head/neck, shoulder complex, upper limb, trunk, pelvis, hip and lower limb.

3. These body segments are then observed during one phase of gait at a time. For example, watch the whole body during stance phase of the left lower limb (incorporating right lower limb swing phase) and then repeat the observation during right lower limb stance phase (incorporating left lower limb swing phase).

4. The therapist should observe each body segment in terms of:

General alignment of body segments

Changes to normal gait cycle, including omissions from and alterations in sequence and timing. For example, no heel strike, no terminal hip extension, decreased stride length, increased foot angle or uncontrolled foot placement

Abnormal movements, e.g. associated reactions in the upper limb (S3.18). Again it is important to note the timing of these reactions for accurate analysis

5. The therapist should, where appropriate, assess the patient walking in different directions (forwards, backwards, sideways, turning) and in different contexts (indoors on various surfaces and outdoors on uneven surfaces).

6. Foot and ankle: The foot provides the main source by which muscle recruitment is adapted during gait (Holland and Lynch-Ellerington 2009). Therefore the mobility of the foot and ankle joints and the stability gained from intrinsic muscles may require particular attention. This may be carried out later in the objective assessment.

Recording

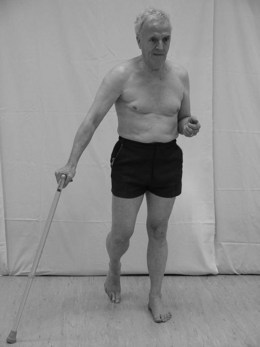

A text description of the deficits of gait may be structured under the relevant phase of gait or related to body segments. The example below relates to Figure 19.3.

Figure 19.3 Gait analysis of left stance phase.

Example

During left stance phase/right swing phase:

Head and neck: left side flexed with slight right rotation

Shoulder complex: left side rotated backwards

Trunk: left side rotated backwards

UL, left: pt exhibits an associated reaction (glenohumeral joint extended with elbow flexed to 90°, forearm supination and finger flexion). This associated reaction is increased during left stance and decreases during right stance

UL, right: pt tends to hold walking stick far out to the right

Pelvis: left side rotated backwards

Hip, left: slight medial rotation. Pt unable to achieve terminal extension

Hip, right: slight abduction and external rotation

Ankle/Foot, left: unable to gain flat foot

Ankle/foot, right: pt tends to take a quick short step through.

References and Further Reading

Holland, A, Lynch-Ellerington, M. The control of locomotion. In: Raine S, Meadows L, Lynch-Ellerington M, eds. Bobath concept: theory and clinical practice in neurological rehabilitation. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Magee, DJ. Orthopaedic physical assessment, ed 4. Canada: Elsevier Sciences; 2006.

Moore, S, Schurr, K, Wales, A, et al. Observation and analysis of hemiplegic gait: stance phase. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 1993; 39:259–267.

Moore, S, Schurr, K, Wales, A, et al. Observation and analysis of hemiplegic gait: swing phase. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy. 1993; 39:271–278.

Shumway-Cook, A, Woollacott, MH. Motor control: translating research into clinical practice, ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2007.

SiliconCOACH. SiliconCOACH Coaching solutions for a digital age [online]. New Zealand www.siliconcoach.com, 2004. [(Accessed 1 September 2006)].