G

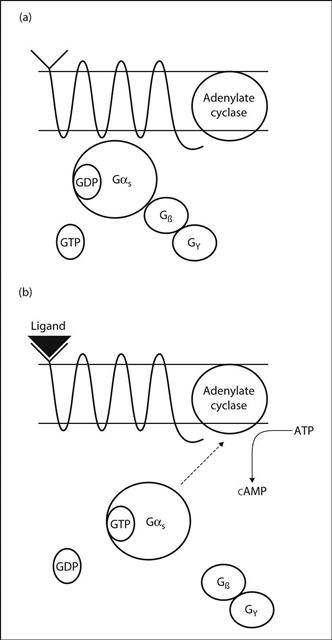

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Large family of transmembrane receptors that bind a wide variety of ligands, including neurotransmitters and hormones. The target receptors of many drugs, including adrenergic, dopamine, opioid, 5-HT and histamine agents. The receptor consists of seven membrane-spanning helices bound on the inner surface of the membrane to a G protein, so called because they bind guanine diphosphate (GDP) and triphosphate (GTP). G proteins consist of three subunits: Gα, Gβ and Gγ. In the inactive state, Gα has GDP on its binding site (Fig. 75a). Activation of the GPCR by a ligand causes an allosteric change in the Gα subunit, resulting in the displacement of GDP and replacement by GTP; the Gβ and Gγ subunits dissociate from the complex (Fig. 75b). The activated Gα subunit in turn activates an effector molecule, e.g. adenylate cyclase (see Fig. 5; Adenylate cyclase). Activated Gα is a GTPase that rapidly reconverts GTP to GDP, thus restoring the G protein to its inactive state.

Many types of Gα subunit exist, including:

In addition to their coupling to second messenger systems, G proteins can also be directly coupled to ion channels. They have been investigated as possible sites for interaction with anaesthetic agents.

Hollmann MW, Danja Strumper D, Herroeder S, Durieux ME (2005). Anesthesiology; 103: 1066–88

G proteins, see G protein-coupled receptors

G6PD deficiency, see Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

GABA, see γ-Aminobutyric acid

Gabapentin. Oral anticonvulsant drug, also used in chronic pain management. In epilepsy, used mainly as add-on therapy for partial seizures. Is also useful as an adjunct for reducing postoperative pain and PONV. Although structurally related to GABA, it is thought to act by blocking voltage-gated calcium channels in the CNS. Peak plasma levels occur within 2–3 h of administration, with half-life of 5–7 h. Excreted renally.

Gabexate mesilate. Synthetic serine protease inhibitor; has been studied as a protective and therapeutic agent in pancreatitis, as a neuroprotective agent in spinal cord injury, and as a treatment for DIC. Not available in the UK.

Gag reflex. Elevation and constriction of the pharynx following stimulation of the posterior pharyngeal wall. The afferent pathway is via the glossopharyngeal nerve; the efferent is via the vagus. Elevation of the soft palate when it is touched relies on afferent fibres in the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve; often the two reflexes are elicited together. The gag reflex is abolished following local anaesthesia and lesions of the pharynx, lesions involving the vagal nuclei in the medulla, and deep anaesthesia or coma. Absence of the gag reflex may indicate that the airway is at risk, e.g. from aspiration of vomit. The reflex is assessed as part of testing for brainstem death.

Gain, electrical. Ratio of output signal amplitude to input signal amplitude. Thus a measure of amplification of signal, e.g. in monitoring equipment. May be specified as voltage, current or power gain; expressed as a simple ratio, or for power gain, also expressed as logarithm (base 10) of the ratio (e.g. in bels or decibels).

Gallamine triethiodide, see Neuromuscular blocking drugs

Galvanic skin response (Skin conductance response; Sympathogalvanic response). Measurement of the skin’s electrical conductivity, which varies with its moisture level. Test of sympathetic afferent, efferent and spinal interconnecting pathways, used to assess the effects of sympathetic nerve blocks. Has also been used to assess other regional blocks in which sympathetic blockade occurs, e.g. epidural anaesthesia, brachial plexus block.

Skin electrodes are placed on dorsal and ventral surfaces of the hand/foot, with a reference electrode elsewhere. Opposite sides of the body are normally compared. The output is displayed on an oscilloscope (e.g. ECG machine); a steady line results. With intact sympathetic pathways, pinching the skin causes altered skin conductance via changes in sweat gland secretion, displayed as a deflection lasting under 5 s. Deflection is abolished by successful blockade. The response may be diminished by use of atropine, repeated testing and in the elderly.

Ganciclovir. Antiviral drug, related to aciclovir but more active against cytomegalovirus and more toxic, thus reserved for severe infections and to prevent infection during immunosuppression following organ transplantation. Valganciclovir, a prodrug, is available for oral use.

Ganglion blocking drugs. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonists acting at autonomic ganglia. The first antihypertensive drugs, now rarely used because of widespread side effects caused by sympathetic blockade (postural and exertional hypotension, decreased sweating) and parasympathetic blockade (constipation, urinary retention, impotence, dry mouth, blurring of vision). May first stimulate then block receptors (e.g. nicotine) or exhibit competitive antagonism (e.g. hexamethonium, pentolinium, trimetaphan). None is generally available in the UK.

Because of the similarity between neuromuscular and ganglionic nicotinic receptors, ganglion blockers (e.g. hexamethonium) may cause neuromuscular blockade, and neuromuscular blocking drugs (e.g. tubocurarine) may cause ganglion blockade.

Gangrene. Death and decay of body tissues; usually a consequence of ischaemia ± bacterial decomposition but may be caused by micro-organisms in well-perfused tissue (e.g. gas gangrene). Traditionally a clinical diagnosis, thus described according to the causative insult and clinical appearances, even though some of the terms are now obsolete: traumatic gangrene (resulting from direct injury); gas gangrene (associated with gas formation within the tissues); Fournier’s gangrene (affecting the perineum); wet gangrene (associated with venous congestion and oedema); dry gangrene (affected tissue is blackened and shrunken). Many terms have been superseded by more specific ones, e.g. necrotising fasciitis.

Gas. Form of matter whose constituent molecules or atoms are constantly moving, and whose mean positions are far apart. Tends to expand in all directions, and diffuse and mix with other gases. Governed by the gas laws under specified conditions. Formed when a liquid exceeds its critical temperature. The constituent particles are sufficiently far apart for the forces (e.g. Van der Waals forces) between them to be almost negligible, unless the gas is compressed. Pressure exerted by a gas is proportional to the number of collisions of atoms/molecules against the container’s walls (which is proportional to the number of gas molecules in the container).

Gas analysis. Possible methods:

– gas reacts chemically with other substances to form non-gaseous compounds, with reduction of overall volume (e.g. Haldane apparatus) or pressure (e.g. van Slyke apparatus). Alternatively, the reaction results in emission of light that is measured by a photodetector, e.g. chemiluminescence nitric oxide analysis (NO + ozone producing O2 + NO2 + light).

– spectroscopy (e.g. infrared).

– adsorption of vapours on to surfaces:

– gas chromatography and detectors, e.g. katharometer, flame ionisation detector, electron capture detector.

– fuel cell, and paramagnetic and polarographic analysers, used for O2 measurement.

[Heinrich Dräger (1847–1917), German engineer; Carl-Gunnar Engström (1912–1987), Swedish physician]

Gas chromatography. Technique used for gas analysis. The sample mixture is injected into a stream of inert carrier gas (the mobile phase) that passes through a column of silica–alumina particles coated in oil or wax (the stationary phase). Separation of the sample component gases occurs along the column’s length, depending on their relative solubilities in the two phases. Temperature of the column is carefully controlled. Liquids may also be analysed. Suitable detectors (e.g. katharometer, flame ionisation detector or electron capture detector) are required.

Gas flow. Principles of flow are as for any fluid. Clinical applications:

flow is turbulent in the upper airway, trachea and bronchi, especially during forceful breathing; i.e. gas density is more important than viscosity. Thus in upper airway obstruction, flow is increased if low-density gas is used, e.g. helium–oxygen mixture.

flow is turbulent in the upper airway, trachea and bronchi, especially during forceful breathing; i.e. gas density is more important than viscosity. Thus in upper airway obstruction, flow is increased if low-density gas is used, e.g. helium–oxygen mixture.

Turbulence usually occurs in anaesthetic breathing systems during peak flow, especially if sharp-angled bends are present, e.g. at connections between components. Turbulence is more likely with narrow tubing and tubes.

Turbulence usually occurs in anaesthetic breathing systems during peak flow, especially if sharp-angled bends are present, e.g. at connections between components. Turbulence is more likely with narrow tubing and tubes.

other applications include the Venturi principle, fluidics, flow–volume loops and flowmeters.

other applications include the Venturi principle, fluidics, flow–volume loops and flowmeters.

Gas gangrene. Infection due to clostridium species, usually C. perfringens, a spore-forming Gram-positive anaerobic bacillus found in soil and faeces. Classically associated with deep war wounds, especially those contaminated with dirt or foreign bodies, but may follow any trauma, e.g. surgery. The incubation period is under 4 days, usually under 1 day.

The organism produces gas within tissues, often detectable clinically as subcutaneous emphysema. Local spread is rapid, with oedema, pain and tissue necrosis; endotoxin production often results in sepsis with MODS.

Prevented and treated by wound debridement and cleaning. Penicillin is an effective adjunct. Hyperbaric O2 therapy has been used to increase local tissue O2 content; antitoxin therapy is more controversial.

Gas laws, see Avogadro’s hypothesis; Boyle’s law; Charles’ law; Dalton’s law; Henry’s law; Ideal gas law

Gas transport, see Carbon dioxide transport; Oxygen transport

Gasp reflex. Production of a deep slow breath following a large positive pressure inflation of the lungs. Originally described in cats and dogs, but may be seen in newborn babies; during neonatal resuscitation, it may occur within primary apnoea. A similar response may also be seen after opioid administration in anaesthetised patients.

Head’s paradoxical reflex, although similar, is produced under different experimental circumstances.

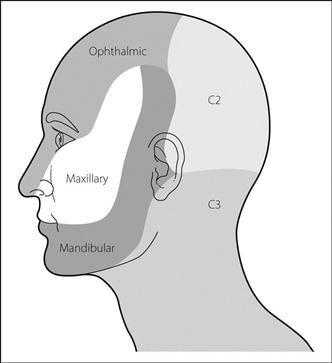

Gasserian ganglion block. Block of the trigeminal ganglion which lies medially in the middle cranial fossa within a dural reflection (Meckel’s cave), lateral to the internal carotid artery and cavernous sinus. Results in anaesthesia of the face, forehead and anterior scalp (Fig. 76). Used mainly for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia, but also for surgery to the face. Performed using X-ray imaging to guide needle positioning.

Fig. 76 Innervation of the face

after careful aspiration, 1–2 ml solution, e.g. 1% lidocaine, is injected. Alcohol injection or thermocoagulation may follow if ablative therapy is required. Accidental subarachnoid injection may occur.

after careful aspiration, 1–2 ml solution, e.g. 1% lidocaine, is injected. Alcohol injection or thermocoagulation may follow if ablative therapy is required. Accidental subarachnoid injection may occur.

Often painful; general anaesthesia or sedation may be employed, with waking up or reversal to confirm paraesthesia, followed by resedation for ablation. Propofol or a midazolam/flumazenil combination has been used. Complications include anaesthesia dolorosa.

[Johann Gasser (1723–1765), Austrian anatomist;

Johann Meckel (1714–1774), German anatomist]

See also, Mandibular nerve block; Maxillary nerve block; Ophthalmic nerve block

Gastric contents. Anaesthetic importance:

absorption of orally administered drugs; e.g. related to gastric emptying, pH and drug interactions within the stomach.

absorption of orally administered drugs; e.g. related to gastric emptying, pH and drug interactions within the stomach.

aspiration of gastric contents; severity of aspiration pneumonitis is related to the pH and volume of aspirate, although the particulate nature of the aspirate is also important.

aspiration of gastric contents; severity of aspiration pneumonitis is related to the pH and volume of aspirate, although the particulate nature of the aspirate is also important.

• Gastric secretion is increased by:

presence of food in the mouth (vagal reflex).

presence of food in the mouth (vagal reflex).

presence of food in the stomach (local reflex).

presence of food in the stomach (local reflex).

protein meal, via duodenal gastrin secretion.

protein meal, via duodenal gastrin secretion.

increased sympathetic nervous system activity (e.g. anxiety, fear, pain).

increased sympathetic nervous system activity (e.g. anxiety, fear, pain).

mechanical obstruction and duodenal distension.

mechanical obstruction and duodenal distension.

labour (little effect unless opioids given).

labour (little effect unless opioids given).

drugs, e.g. opioid analgesic drugs, anticholinergic drugs, alcohol, dopamine.

drugs, e.g. opioid analgesic drugs, anticholinergic drugs, alcohol, dopamine.

drugs, e.g. metoclopramide, domperidone (opioid-induced gastric stasis is not reversed; cf. cisapride).

drugs, e.g. metoclopramide, domperidone (opioid-induced gastric stasis is not reversed; cf. cisapride).

Rate of emptying is important because of the risks of nausea, vomiting, regurgitation and aspiration of gastric contents. Emptying also affects absorption of orally administered drugs. A commonly used preoperative starvation guideline is 6 h for solid food/milk and 2 h for water in all but life-threatening emergencies; this is an estimate and gastric contents may be considerable even after fasting if gastric emptying is delayed. Small volumes of water (150 ml) given 2–3 h preoperatively have been shown to reduce the volume and acidity of gastric contents. Recent guidelines call for withholding of all solid food on the day of surgery, unrestricted clear fluids up to 3 h preoperatively and consideration of H2 receptor antagonists for patients at risk.

serial nasogastric aspiration, with measurement of orally administered marker substance.

serial nasogastric aspiration, with measurement of orally administered marker substance.

measurement of impedance across the lower chest/upper abdomen; alters as composition of tissues, i.e. gastric contents, changes.

measurement of impedance across the lower chest/upper abdomen; alters as composition of tissues, i.e. gastric contents, changes.

oral administration of radioisotope, with measurement of radioactivity over the stomach.

oral administration of radioisotope, with measurement of radioactivity over the stomach.

Emetic drugs are no longer used.

Gastric intramucosal pH, see Gastric tonometry

Gastric lavage. Formerly performed following poisoning and overdose; now considered to have a very limited role, as evidence suggests risk of harm outweighs benefit in the majority of cases.

Gastric tonometry. Indirect method of measuring gastric intramucosal pH, which in turn is used as an indicator of gastric (and therefore GIT) mucosal O2 balance. Intramucosal acidosis may indicate impaired GIT O2 delivery or impaired utilisation, and has been proposed as a useful indicator of poor splanchnic perfusion and mortality; may be used to guide vasoactive drug therapy in the ICU and during major surgery.

A tonometer incorporating a saline-filled balloon is placed via the oesophagus into the stomach, and luminal PCO2 (which approximates to intramucosal PCO2) determined by measuring PCO2 in the saline. A gas-filled balloon has also been used, with recirculation of gas into and out of the balloon with continuous measurement of PCO2 at the distal end of the system. H2 receptor antagonists eliminate the effect of gastric acid, combining with pancreatic bicarbonate to produce CO2. Direct measurement is also possible but involves mucosal trauma and is less reliable. Arterial bicarbonate concentration is measured simultaneously and approximates to mucosal concentration, allowing calculation of intramucosal pH (pHi).

Kolkman JJ, Otte JA, Groeneveld ABJ (2000). Br J Anaesth; 84: 74–86

Gastrointestinal haemorrhage. May arise from any part of the GIT, although most acute bleeds are caused by gastric or duodenal ulcers or erosions. May result in the need for one or more of resuscitation, surgery or ICU management. Mortality is 5–10% (higher in certain conditions, e.g. 30% in oesophageal varices). Features range from obvious gross haematemesis to vomiting of small amounts of ‘coffee grounds’ (blood altered by gastric acid) or the passage of melaena.

of the underlying cause, e.g. oesophageal varices associated with alcoholism; NSAID-induced ulceration associated with arthritic disease; the possibility of coagulation disorders; systemic effects of malignancy.

of the underlying cause, e.g. oesophageal varices associated with alcoholism; NSAID-induced ulceration associated with arthritic disease; the possibility of coagulation disorders; systemic effects of malignancy.

haemorrhage and hypovolaemia.

haemorrhage and hypovolaemia.

presence of a full stomach and the risk of aspiration of gastric contents.

presence of a full stomach and the risk of aspiration of gastric contents.

difficulty securing the airway whilst there is copious haematemesis.

difficulty securing the airway whilst there is copious haematemesis.

O2, volume resuscitation, correction of coagulation disorders.

O2, volume resuscitation, correction of coagulation disorders.

specific management, e.g. oesophageal varices.

specific management, e.g. oesophageal varices.

GIT haemorrhage associated with stress ulcers may occur in critically ill patients on the ICU.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux. Normally prevented by the lower oesophageal sphincter and anatomical arrangement of the oesophagus and stomach. Common in hiatus hernia and obesity. May cause burning retrosternal pain and regurgitation of bitter fluid into the mouth, especially on stooping/lying. Associated oesophagitis may cause pain after meals. Medical treatment is as for peptic ulcer disease/hiatus hernia, including weight loss and avoidance of the supine/head-down position. Anaesthetic management is as for hiatus hernia.

Gastro-oesophageal sphincter, see Lower oesophageal sphincter

Gastroschisis and exomphalos. Congenital malformations of the abdominal wall, associated with protrusion of abdominal contents:

fluid and electrolyte balance.

fluid and electrolyte balance.

the bowel is covered with a dry towel/plastic bag.

the bowel is covered with a dry towel/plastic bag.

primary surgical closure is preferable to delayed closure if possible.

primary surgical closure is preferable to delayed closure if possible.

• Anaesthetic considerations: as for paediatric anaesthesia plus the above considerations. In addition:

N2O diffuses into the bowel, increasing its size, and is avoided.

N2O diffuses into the bowel, increasing its size, and is avoided.

abdominal closure may be difficult, with increased intra-abdominal pressure. Postoperative IPPV may be necessary. Staged closure may be performed using a Silastic pouch if adverse effects of primary closure (e.g. impaired lung compliance) are excessive.

abdominal closure may be difficult, with increased intra-abdominal pressure. Postoperative IPPV may be necessary. Staged closure may be performed using a Silastic pouch if adverse effects of primary closure (e.g. impaired lung compliance) are excessive.

postoperative nutrition and prevention/treatment of infection are important.

postoperative nutrition and prevention/treatment of infection are important.

Raghavan M, Montgomerie J (2008). Paediat Anaesth; 18: 731–5

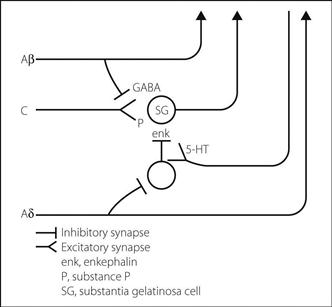

Gate control theory of pain. Proposed in 1965 by Melzack and Wall to account for the influence of psychological and physiological variables on pain transmission. Suggests that impulses flow from periphery to brain through a ‘gate’ at spinal level, the opening or closure of which is influenced by other neural pathways. Pain is felt when impulse flow exceeds a certain critical level. The gate is closed by descending and large ascending (Aβ) fibres and opened by small ascending (C) fibres. It is thought to be located in the substantia gelatinosa (SG), laminae II and III of the dorsal horn; interneurones project to target cells that then project cranially. The theory has since been modified to account for expanding experimental and clinical evidence of neurotransmitter and receptor involvement (Fig. 77):

Fig. 77 Gate control theory of pain

C fibres from deep receptors (e.g. chemical damage) project to SG cells, probably via substance P (opens gate). Cranial projection is via spinoreticular fibres.

C fibres from deep receptors (e.g. chemical damage) project to SG cells, probably via substance P (opens gate). Cranial projection is via spinoreticular fibres.

Aβ fibres (activated by e.g. high-frequency, low-amplitude TENS) inhibit the above synapse presynaptically; GABA is thought to be the neurotransmitter (closes gate). The Aβ fibres also project cranially.

Aβ fibres (activated by e.g. high-frequency, low-amplitude TENS) inhibit the above synapse presynaptically; GABA is thought to be the neurotransmitter (closes gate). The Aβ fibres also project cranially.

Aδ fibres from superficial receptors (e.g. temperature, pinprick, acupuncture, low-frequency TENS) project cranially, via spinothalamic fibres. Cause 5-HT-mediated descending pathways to close the gate via enkephalin-secreting interneurones acting on target cells.

Aδ fibres from superficial receptors (e.g. temperature, pinprick, acupuncture, low-frequency TENS) project cranially, via spinothalamic fibres. Cause 5-HT-mediated descending pathways to close the gate via enkephalin-secreting interneurones acting on target cells.

[Patrick D Wall (1925–2001), English neuroscientist;

Ronald Melzack, Montreal psychologist]

Gauge. Measure of thickness/width; applied in medicine to cannulae, needles and catheters. Common systems include wire gauges used for needles and cannulae and the French gauge (Charrière), originally applied to urinary catheters and which equals external circumference in mm (approximately 3 × external diameter).

Gay-Lussac’s law, see Charles’ law

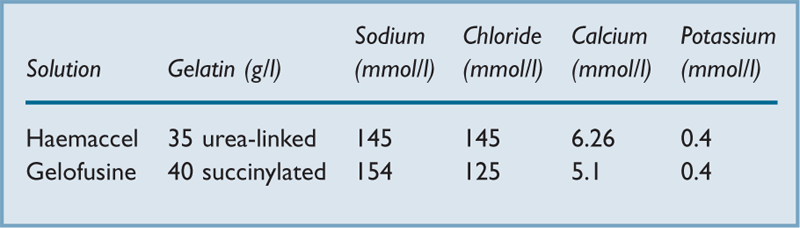

Gelatin solutions. Colloid solutions derived from animal gelatin, a derivative of collagen. Commonly used forms contain urea-linked (Haemaccel) or succinylated (Gelofusine) gelatin components (Table 21); average mw is about 35 kDa. Used clinically as plasma substitutes, e.g. in haemorrhage and shock. Cheaper than albumin solutions and starch solutions, but with shorter half-life (about 4 h). Only 1% metabolised with no accumulation in reticuloendothelial system. Allergic (anaphylactoid) reactions have followed rapid infusion, especially of Haemaccel (said to be reduced in its current form); usually mild but occasionally severe. The incidence of reactions is less than 0.15%.

Renal function and blood compatibility testing are unaffected. Gelatin solutions may interfere with platelet function and coagulation (via reduction in von Willebrand factor activity) and restriction of their administration in major haemorrhage has been suggested, although this is controversial. The calcium in Haemaccel may coagulate stored blood if infused through the same giving set without first flushing with saline.

Table 21 Components of gelatin solutions

Gelofusine, see Gelatin solutions

Gender differences and anaesthesia. Many factors may contribute to differences in responses to anaesthetic and analgesic drugs between genders, for example:

– distribution: greater fat : water ratio in women; thus volume of distribution of water-soluble drugs (e.g. vecuronium) is reduced, and of fat-soluble drugs (e.g. diazepam) is increased. It has been suggested that women recover more quickly after propofol anaesthesia than men.

– metabolism: e.g. greater metabolism of morphine to the active 6-glucuronide than the antagonistic 3-glucuronide in women, compared to men. Other differences may relate to sex-specific isoenzyme systems but experimental results are often conflicting.

– excretion: renal excretion is affected by body weight and composition.

pharmacodynamics: women are thought to be more susceptible to the analgesic effects of opioid analgesic drugs and neuromuscular blocking drugs and, although different pharmacokinetics may contribute, pharmacodynamic factors have also been suggested. Reduced sensitivity and earlier waking of women after propofol may also be a pharmacodynamic phenomenon.

pharmacodynamics: women are thought to be more susceptible to the analgesic effects of opioid analgesic drugs and neuromuscular blocking drugs and, although different pharmacokinetics may contribute, pharmacodynamic factors have also been suggested. Reduced sensitivity and earlier waking of women after propofol may also be a pharmacodynamic phenomenon.

Further differences may result from cyclical changes in body fluid and hormonal status during the menstrual cycle (e.g. PONV may be affected by phase of menstrual cycle). There are also significant effects of pregnancy. Psychological factors and the reported greater incidence of adverse effects in women may also contribute to apparent differences between the sexes.

Buchanan FF, Myles PS, Cicuttini F (2011). Br J Anaesth; 106: 823–9

Genitofemoral nerve block, see Inguinal hernia field block

Gentamicin. Broad-spectrum antibacterial drug of the aminoglycosides group, especially active against Gram-negative organisms, but poorly active against haemolytic streptococci, haemophilus and anaerobes; thus often given with a penicillin ± metronidazole when given empirically. <10% protein-bound and excreted renally, with plasma half-life of 2–3 h with normal renal function.

Geriatric patient, see Elderly, anaesthesia for

GHBA, see γ-Hydroxybutyric acid

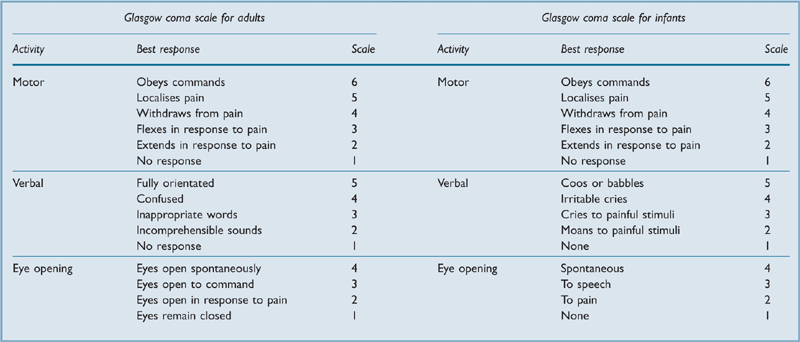

Glasgow coma scale (GCS). Scoring system originally devised in 1974 for assessment of patients with head injury but now widely applied to other causes of coma. Validated as useful predictor of outcome after head injury, intracranial haemorrhage, subarachnoid haemorrhage, poisonings and cardiac arrest. Originally described for adults, it has been modified for use in infants. A maximum of 15 points may be scored (Table 22), expressed as a total or, more usefully, separated into the three categories (e.g. ‘M3, V2, E2’ gives more information than ‘GCS 7’). Changes in scores over time are more useful than single values. Despite its major limitation of inability to assess patients unable to speak (e.g. aphasia, intubation) because of its reliance on a verbal component, it remains the most widely used coma scale and is a component of the APACHE scoring system.

Glaucoma. Damage to the eye associated with raised intraocular pressure (IOP).

– avoidance of drugs that raise IOP, e.g. ketamine. Systemic atropine is safe; topical use may cause mydriasis and obstruction of drainage of aqueous humour.

– IOP increases following tracheal intubation and extubation.

– avoidance of: trauma to the eye; steep head-down position; coughing and straining.

– IOP may be reduced by specific measures, e.g. iv mannitol, acetazolamide.

related to concurrent drug therapy:

related to concurrent drug therapy:

– timolol drops and related drugs: systemic absorption and β-blockade may occur.

– ecothiopate drops: may prolong suxamethonium’s action.

– pilocarpine and physostigmine drops: systemic absorption and bradycardia may occur.

– acetazolamide: electrolyte imbalance may occur.

– cannabis may be used by patients with glaucoma, although evidence that it lowers IOP is scant.

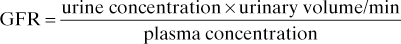

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR). Volume of plasma filtered by the kidneys per unit time. Normally 120 ml/min (173 l/day).

effective glomerular surface area: reduced by contraction of mesangial cells within the glomerulus, e.g. in response to angiotensin II, vasopressin, noradrenaline, leukotrienes, histamine and certain prostaglandins. Dopamine and atrial natriuretic peptide cause relaxation.

effective glomerular surface area: reduced by contraction of mesangial cells within the glomerulus, e.g. in response to angiotensin II, vasopressin, noradrenaline, leukotrienes, histamine and certain prostaglandins. Dopamine and atrial natriuretic peptide cause relaxation.

hydrostatic gradient across the capillary walls. Affected by:

hydrostatic gradient across the capillary walls. Affected by:

– renal blood flow and arteriolar tone (e.g. noradrenaline constricts the afferent arterioles predominantly, whilst angiotensin II constricts the efferent arterioles). Autoregulation is thought to involve afferent arteriolar vascular tone.

Measured by iv infusion of a substance that is freely filtered and neither reabsorbed nor secreted by the renal tubules. It must also be non-toxic, not metabolised and have no effect on GFR. At steady state, the clearance of the substance is calculated. The volume of plasma cleared per minute then equals the volume filtered per minute, i.e.:

Provides an indication of renal function, but is difficult to measure routinely. Creatinine clearance approximates to GFR, and is commonly measured instead. Creatinine is actually secreted by the renal tubules to a small degree, but measurement of plasma levels overestimates by a small amount, tending to cancel any error.

oliguria, salt and water retention, hypervolaemia and hypertension due to impaired glomerular filtration (nephritic syndrome). Classically follows streptococcal infection.

oliguria, salt and water retention, hypervolaemia and hypertension due to impaired glomerular filtration (nephritic syndrome). Classically follows streptococcal infection.

proteinuria, causing hypoproteinaemia and marked oedema if severe (nephrotic syndrome).

proteinuria, causing hypoproteinaemia and marked oedema if severe (nephrotic syndrome).

others: hypertension, haematuria, loin pain, renal failure (acute and chronic).

others: hypertension, haematuria, loin pain, renal failure (acute and chronic).

drug therapy: may include antihypertensive drugs and corticosteroids.

drug therapy: may include antihypertensive drugs and corticosteroids.

Glomus tumours. Rare benign tumours arising from glomus bodies (arteriovenous anastomoses adjacent to blood vessels, receiving rich sympathetic tone and involved in regulating local blood flow and skin temperature). More common in the limbs, but may arise from the glomus jugulare (tympanic body) in the upper jugular bulb. The latter may extend into the cerebellum and brainstem, middle ear, internal jugular vein or laterally into the neck. Thus associated with neurological lesions, including of lower cranial nerves. May rarely secrete catecholamines or 5-HT. Anaesthetic concerns include length of surgery and blood loss, and those of neurosurgery.

Glossopharyngeal nerve block. Used to supplement topical anaesthesia and/or superior laryngeal nerve block, e.g. in awake intubation. Also used for tonsillectomy and glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Acute airway obstruction has followed its use for awake intubation and post-tonsillectomy analgesia.

– posterior: having applied topical anaesthesia to the tongue, it is depressed and an angled needle inserted behind the middle of the posterior tonsillar pillar, to 1 cm depth. After aspiration, 3 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected. Blocks the sensory pharyngeal, lingual and tonsillar branches, and the motor branch to stylopharyngeus. Carotid puncture is more likely using this approach than with the anterior.

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Recurrent, sudden, stabbing pain in the distribution of the glossopharyngeal nerve. May result from nerve compression by vertebral or posterior inferior cerebellar arteries, local musculoskeletal anomalies or trauma. May be relieved by topical local anaesthetic to oropharyngeal trigger areas. Treatment includes glossopharyngeal nerve block using local anaesthetic at weekly intervals; alcohol injection or surgical decompression of the glossopharyngeal nerve may be required.

Glucagon. Polypeptide hormone secreted by the A (α) cells of pancreatic islets. Acts on the glucagon receptor (a G protein-coupled receptor), resulting in hepatic adenylate cyclase stimulation, leading to glycogen breakdown and release of glucose (hence its emergency use in hypoglycaemia). Also increases hepatic gluconeogenesis from amino acids, and breakdown of fats to form ketone bodies. Stimulates secretion of growth hormone, insulin and somatostatin. Has inotropic and chronotropic actions on the heart, unrelated to adrenergic receptors. Thought to increase calcium transport into myocardial cells, possibly via adenylate cyclase activation; used in the treatment of β-adrenergic receptor antagonist poisoning. Half-life is less than 10 min.

Secretion is increased by β-adrenergic stimulation, stress, exercise, amino acids, gastrin, cholecystokinin and starvation. It is decreased by hyperglycaemia, somatostatin, ketone bodies, fatty acids, insulin and α-adrenergic stimulation.

Glucocorticoids. Hormones secreted by the adrenal cortex; consist mainly of cortisol and corticosterone. Diffuse through cell membranes and act on intracellular receptors, causing changes in gene transcription, protein synthesis and cell function. Secretion is increased by ACTH.

• Actions:

increased glycogen and protein breakdown, and glucose synthesis, with increased blood glucose levels.

increased glycogen and protein breakdown, and glucose synthesis, with increased blood glucose levels.

required for normal effects of catecholamines on metabolism, bronchi, CVS and fluid balance. This may explain the hypotension seen in adrenocortical insufficiency.

required for normal effects of catecholamines on metabolism, bronchi, CVS and fluid balance. This may explain the hypotension seen in adrenocortical insufficiency.

required for efficient muscle contraction and nerve conduction; also involved in inflammatory/immunological responses.

required for efficient muscle contraction and nerve conduction; also involved in inflammatory/immunological responses.

mild aldosterone-like activity.

mild aldosterone-like activity.

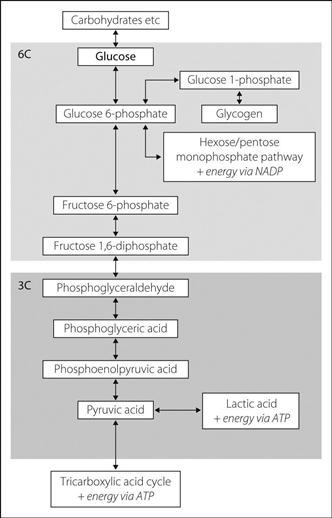

Glucose. Carbohydrate, of central importance as an energy source within the body.

• Main metabolic pathways (Fig. 78):

– from breakdown of carbohydrate foodstuffs.

– from glycogen, protein and fats via intermediate steps in glucose metabolism; occurs in the liver during starvation and exercise. Produces glucose 6-phosphate, which is converted by hepatic glucose 6-phosphatase to glucose, which enters the bloodstream. Other tissues (e.g. muscle) lack this enzyme, and glucose 6-phosphate is catabolised directly via the glycolytic pathway.

– from the GIT via carrier-assisted transport, i.e. as part of an active transport mechanism for sodium ions. Thus indirectly utilises energy.

– from the bloodstream into cells by the action of insulin.

utilisation for energy production: via conversion into glucose 6-phosphate and subsequent breakdown (glycolysis).

utilisation for energy production: via conversion into glucose 6-phosphate and subsequent breakdown (glycolysis).

conversion to glycogen via glucose 6-phosphate and glucose 1-phosphate.

conversion to glycogen via glucose 6-phosphate and glucose 1-phosphate.

Fasting plasma levels are maintained at 4–6 mmol/l (72–108 mg/dl) by the action of various hormones mainly on the liver; e.g. insulin decreases blood glucose, whilst glucagon, catecholamines, growth hormone, glucocorticoids and thyroid hormones increase it.

Filtered and reabsorbed in the proximal tubules of the kidneys; renal capacity for reabsorption is exceeded above plasma levels of about 10 mmol/l (180 mg/dl). Congenital inability to reabsorb glucose results in renal glycosuria at normal plasma levels. The renal threshold may also be reduced in pregnancy and tubular damage.

See also, Catabolism; Diabetes mellitus; Metabolism; Nutrition

Glucose–insulin–potassium infusion. Infusion regimen used in an attempt to reduce the size of MI, increase cardiac output and reduce arrhythmias. First used in the 1960s but abandoned because of doubts over its efficacy; more recent evidence has suggested a reduction in mortality. Thought to reduce plasma free fatty acid levels, reducing myocardial energy and O2 requirements; it possibly augments anaerobic metabolism by increasing ATP supply. Regimens vary but most involve 25–50 units insulin and 40–50 mmol potassium added to 500 ml of 25–50% glucose, infused iv at 100 ml/h. Glucose/insulin infusion has also been used in hyponatraemia due to the ‘sick cell syndrome’; it supposedly restores ionic balance.

Glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency (G6PD deficiency). X-linked recessive inherited disorder of red blood cell metabolism, common in Mediterranean, African, Middle Eastern and South-East Asian populations. Impairs the hexose monophosphate shunt of glucose metabolism, required for cell protection against products of oxidation. Results in haemolysis, which may be chronic or associated with acute illness (especially typhoid and viral hepatitis infection), drugs (e.g. antimalarials, sulphonamides, aspirin and related drugs, methylthioninium chloride [methylene blue]), and ingestion of broad beans (favism). Reduction of methaemoglobin is impaired, thus avoidance of prilocaine has been suggested.

Classified according to degree of enzyme activity; Class 1 is severely deficient; Class 2 has 1–10% normal activity; Class 3 10–60%; Classes 4 and 5 have increased activity. Provides some protection against falciparum malaria.

Chronic haemolysis is also associated with other inborn errors of metabolism, e.g. pyruvate kinase deficiency.

Glucose reagent sticks. Plastic strips bearing reagents, used to measure glucose concentration, e.g. in blood or urine. Glucose is converted by glucose oxidase to gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide, the latter oxidising a dye to produce a colour change. Accuracy is increased by using reflectance colorimeters to quantify the colour change, and may be reduced by use of alcohol swabs for cleaning the skin. They are less accurate at lower (hypoglycaemic) glucose levels. Useful as a bedside test, and for home monitoring of glucose levels.

Glucose tolerance test. Investigation used in the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Involves administration of glucose either orally or iv, usually the former. 1.75 g/kg is given orally up to 75 g, in at least 250 ml water. Blood glucose normally rises from fasting levels to a peak at 10–60 min, declining thereafter. Fasting and 2-h levels are used for diagnosis:

α-Glucosidase inhibitors. Saccharide hypoglycaemic drugs that compete with saccharidases in the small intestine, thus slowing the breakdown of poly- and disaccharides to monosaccharides in the gut. Used alone or in combination with other drugs to improve glycaemic control, especially postprandial hyperglycaemia. Include acarbose, miglitol and voglibose.

Glue-sniffing, see Solvent abuse

Glutamate. Amino acid and major excitatory neurotransmitter throughout the CNS, especially brain. Released presynaptically, it activates various specific receptors:

AMPA receptors (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors): involved in rapid neurotransmission.

AMPA receptors (α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors): involved in rapid neurotransmission.

kainate (a neurotoxin) receptors: similar effects to those of AMPA receptors.

kainate (a neurotoxin) receptors: similar effects to those of AMPA receptors.

NMDA receptors: slower response; thought to be involved in long-term potentiation, including modulation of pain and memory formation.

NMDA receptors: slower response; thought to be involved in long-term potentiation, including modulation of pain and memory formation.

others, linked to G protein-coupled receptors: less clearly understood.

others, linked to G protein-coupled receptors: less clearly understood.

Manipulation of glutamate pathways is currently an active area of research since it is thought to be involved in pain perception, wakefulness and memory, post-injury or ischaemic neurotoxicity (via glutamate-mediated intracellular calcium accumulation) and spinal cord neurotransmission. It may also have a role in anaesthesia itself, e.g. with ketamine.

Glutamine, see Amino acids; Glutamate

Glyceryl trinitrate (GTN; Nitroglycerin). Vasodilator drug, used to treat myocardial ischaemia and cardiac failure, and to lower BP, e.g. in severe hypertension and hypotensive anaesthesia. Acts via nitric oxide release to affect vascular smooth muscle (mainly venous), lowering preload and reducing SVR and pulmonary vascular resistance. Also increases coronary blood flow. A cutaneous slow-release patch may be applied preoperatively in patients with ischaemic heart disease, and these have also been applied to sites of iv fluid administration, reducing infusion failure by up to 60%. Has also been used to reduce uterine contraction, e.g. in premature rupture of membranes (cutaneous patch) or as an acute tocolytic drug (iv or sublingual).

• Dosage:

orally as slow-release tablets: 2–5 mg tds.

orally as slow-release tablets: 2–5 mg tds.

cutaneously: 5–10 mg/day applied to the chest; 5 mg 3–4-hourly to infusion sites.

cutaneously: 5–10 mg/day applied to the chest; 5 mg 3–4-hourly to infusion sites.

iv: 0.2–5 µg/kg/min. Effects occur within 2–5 min and last 5–10 min after stopping the infusion. Some preparations contain 30–50% propylene glycol and alcohol. GTN is adsorbed on to PVC; polyethylene and rigid plastic/glass infusion sets are acceptable.

iv: 0.2–5 µg/kg/min. Effects occur within 2–5 min and last 5–10 min after stopping the infusion. Some preparations contain 30–50% propylene glycol and alcohol. GTN is adsorbed on to PVC; polyethylene and rigid plastic/glass infusion sets are acceptable.

• Side effects: headache, flushing, hypotension, tachycardia. Tachyphylaxis is common.

Glycine. Amino acid, thought to be active as an inhibitory neurotransmitter at spinal interneurones. Increases membrane chloride conductance, causing postsynaptic hyperpolarisation. May also be involved in inhibitory pathways within the ascending reticular activating system. Also acts as a co-agonist at NMDA receptors. Used as an irrigating solution for TURP. Systemic absorption is thought possibly to be associated with CNS symptoms, e.g. transient blindness, either via central inhibitory pathways or conversion to ammonia.

Glycogen. Storage form of glucose; consists of glucose molecules linked together into a branched polymer. Found mainly in liver and skeletal muscle, and formed from glucose 1-phosphate, derived from glucose 6-phosphate. Glycogenolysis provides glucose for glycolysis, and is increased by adrenaline via liver β-receptors (via cAMP) and α-receptors (via intracellular calcium). Defects in the various storage and breakdown pathways result in the glycogen storage disorders.

Glycogen storage disorders. Inborn errors of metabolism affecting glycogen and glucose metabolism. All are rare, and almost all are autosomal recessive. Classified according to the deficient enzyme and the site of abnormal glycogen storage; 12 types have been described. Common to most are hypoglycaemia and acidosis with hepatomegaly; cardiac, mental and renal impairment may also occur.

• The following are of particular concern:

type II: Pompe’s disease: glycogen is deposited in skeletal, cardiac and smooth muscle. Cardiac failure and generalised muscle weakness are common. The tongue may be enlarged. Enzyme replacement therapy is under investigation.

type II: Pompe’s disease: glycogen is deposited in skeletal, cardiac and smooth muscle. Cardiac failure and generalised muscle weakness are common. The tongue may be enlarged. Enzyme replacement therapy is under investigation.

type V: McArdle’s disease: skeletal muscle phosphorylase deficiency, impairing glycogenolysis. Muscle weakness and myoglobinuria may occur following suxamethonium. Muscle atrophy may follow use of tourniquets for surgery. Hypoglycaemia and acidosis are common.

type V: McArdle’s disease: skeletal muscle phosphorylase deficiency, impairing glycogenolysis. Muscle weakness and myoglobinuria may occur following suxamethonium. Muscle atrophy may follow use of tourniquets for surgery. Hypoglycaemia and acidosis are common.

Glycolysis. Breakdown of glucose (six carbon atoms) to pyruvic acid or lactate (three carbon atoms). Each step in the pathway (see Fig. 78) is catalysed by a specific enzyme. Energy released during the process is utilised by production of ATP. The reactions occur anaerobically, with a net gain of 2 moles of ATP per mole glucose. Under aerobic conditions, pyruvic acid enters the tricarboxylic acid cycle, with a net gain of 36 more moles of ATP. Anaerobic energy production is less efficient; formation of lactate from pyruvate limits ATP production to 2 moles per mole glucose. This may occur in exercising muscle and red blood cells.

Passage of glucose into muscle and fat cells is increased by insulin, with increased glycolysis; most other cell membranes are relatively permeable to glucose. In the liver, glucose 6-phosphatase levels control the rate of glycolysis; insulin causes increased levels and starvation decreased levels.

Other pathways may branch from the glycolytic pathway, e.g. the hexose monophosphate shunt from glucose 6-phosphate in red blood cells. Protein and fat derivatives may enter the glycolytic chain and glycogen may be broken down to glucose 6-phosphate via glucose 1-phosphate.

Glycopeptides. Group of antibacterial drugs; include vancomycin and teicoplanin. Both are true antibiotics since they are derived from micro-organisms. Have bactericidal activity against aerobic and anaerobic Gram-positive organisms, including meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, see Antiplatelet drugs

Glycopyrronium bromide (Glycopyrrolate). Anticholinergic drug, used as premedication and pre- and perioperatively to prevent or treat bradycardia. Also used to prevent muscarinic effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors used to reverse neuromuscular blockade. A quaternary ammonium compound, it does not cross the blood–brain barrier and therefore has minimal central effects, as opposed to atropine and hyoscine. Also less likely to cause tachycardia, mydriasis and blurred vision, but markedly reduces production of sweat and saliva. Its action persists for longer than that of atropine, reducing postoperative bradycardia. Dry mouth may persist postoperatively.

‘Golden hour’. Period following trauma in which active intervention is thought to be crucial in preventing the development of severe organ (especially brain) injury or death. The concept has arisen from the observation that many trauma victims die shortly after the insult; many of the survivors have evidence of persisting brain injury; and experimental brain injury may be considerably exacerbated by subsequent aggravating factors such as hypoxaemia and hypotension (and these two factors in particular are common after severe trauma). Similar considerations are likely to apply to other organs, although to less dramatic or significant extents.

See also, Head injury; Transportation of critically ill patients

Goldman cardiac risk index, see Cardiac risk index

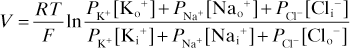

Goldman constant-field equation. Equation used to calculate the membrane potential of a cell. Similar in concept to that of the Nernst equation, utilises the concentrations of sodium, potassium and chloride ions on either side of the membrane, and membrane permeability to each:

= permeability to potassium, sodium and chloride respectively

= permeability to potassium, sodium and chloride respectively

[Ko+], [Nao+], [Clo−] = outside concentration of ions

[Ki+], [Nai+], [Cli−] = inside concentration of ions

[David E Goldman (1910–1998), US physiologist; Michael Faraday (1791–1867), English chemist]

Goodpasture’s syndrome. Combination of glomerulonephritis, rapidly progressive pulmonary haemorrhage and antibodies against glomerular basement membrane (the first two may also occur without these antibodies, e.g. in systemic vasculitides and connective tissue disease, and strictly, do not constitute Goodpasture’s syndrome). The antibodies react against a specific antigen present in the basement membrane and also in the alveolar membrane, hence the association. Often follows an upper respiratory tract infection or exposure to certain chemicals (e.g. following glue sniffing), presumably via formation of new antigenic molecules, resulting in autoantibody formation. Usually responds well to aggressive immunosuppressive therapy if treated early (i.e. before significant renal impairment). Plasmapheresis has been used.

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Potentially life-threatening condition affecting recipients of organ or tissue transplants in which donor inflammatory cells recognise host cells as being ‘foreign’ and mount an inflammatory response against them. Particularly problematic and aggressive when the transplanted cells are immunologically active, e.g. bone marrow transplantation. Acute GVHD typically occurs within 2–3 months of transplantation; affects mainly the skin, liver and GIT, causing rash, hepatic impairment, diarrhoea with sloughing of gut mucosa, and, in severe cases, death. A chronic form may also occur, affecting the same organ systems. Occurs to some extent in up to two-thirds of bone marrow recipients. Thought to be caused by transplanted T lymphocytes, GVHD may be prevented by various immunosuppressive drugs (and anti-T-cell antibodies) and removal of T cells from donor marrow preparations, e.g. with radiation treatment. Activation of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators is also thought to be involved. Treatment is with immunosuppressive drugs (typically ciclosporin and prednisolone), although the response may be poor unless started early. If survived, GVHD may protect against subsequent relapse of leukaemia. GVHD has also been described after intestinal, heart–lung and liver transplantation. A form has also followed blood transfusion, especially in immunocompromised recipients or when first-degree relatives donate blood (involves close mismatch of leucocyte antigen haplotypes). Typically occurs up to a month post-transfusion; features are similar to those above.

Granisetron hydrochloride. 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, licensed as an antiemetic drug in postoperative and radio-/chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Similar to ondansetron.

• Dosage:

PONV: 1 mg slowly iv, repeated up to 2 mg/day.

PONV: 1 mg slowly iv, repeated up to 2 mg/day.

• Side effects: GI upset, headache, Q–T prolongation, arrhythmias.

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Substance used to stimulate neutrophil production, especially in febrile neutropenic patients receiving chemotherapy. Has also been studied as a possible treatment of MODS, SIRS and sepsis. Various recombinant human preparations are available:

Gravity suit, see Antigravity suit

Greener, Hannah (1832–1848). Fifteen-year-old girl, traditionally accepted as being the first recorded death under anaesthesia, although this is probably not the case (see below). She was having a toenail removed under open chloroform anaesthesia in Newcastle in January 1848, when she suddenly collapsed and died, despite attempted revival with brandy.

Griffith, Harold Randall (1894–1985). Canadian anaesthetist in Montreal; famous for the use of curare in anaesthesia in 1942. None of the patients described apparently required respiratory assistance. Active in many other areas of anaesthetic research, including the properties of cyclopropane. Of world renown, he received many honours and medals.

Growth hormone. Polypeptide hormone released from the anterior pituitary gland. Release is increased by:

hypoglycaemia, sleep and exercise.

hypoglycaemia, sleep and exercise.

stress; i.e. produced as part of the stress response to surgery.

stress; i.e. produced as part of the stress response to surgery.

dopamine receptor agonists.

dopamine receptor agonists.

Growth hormone-releasing and inhibiting hormones (the latter is somatostatin) are released by the hypothalamus; growth hormone release is inhibited by growth hormone itself.

G-suit, see Antigravity suit

GTN, see Glyceryl trinitrate

Guanethidine monosulphate. Antihypertensive drug, depleting adrenergic neurones of noradrenaline and preventing its release. Rarely used for hypertension now, but sometimes useful in complex regional pain syndrome; e.g. 10–25 mg in 20 ml saline injected iv into the exsanguinated arm (30–40 mg in 40 ml for leg), and the tourniquet kept inflated for 10–20 min. Close cardiovascular observation is required afterwards; hypotension may be delayed. A small amount of lidocaine is sometimes added. The procedure may be repeated, e.g. on alternate days for a number of weeks, often with long-lasting results.

Guedel, Arthur Ernest (1883–1956). US anaesthetist, practising in Indiana, then California. Considered a pioneer of modern anaesthesia; published extensively on many subjects, including tracheal tube cuffs, divinyl ether, cyclopropane, his pharyngeal airway (see Airways) and a classic description of the stages of anaesthesia. Received many honours and medals.

Guillain–Barré syndrome (Acute inflammatory/postinfectious polyneuropathy). Acute inflammatory polyneuropathy described in 1916, although previously reported by Landry in 1859. Commonest cause of acute paralysis in the Western world. A number of variants are described. 95% of cases have a demyelinating polyneuropathy; in the remainder the axon itself is affected. The Fisher variant is characterised by ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and areflexia. Incidence is 1–2 per 100 000. 60% of cases follow an infective process (usually an upper respiratory tract infection or diarrhoeal illness) within the previous 6 weeks. Infectious agents implicated include campylobacter, mycoplasma, cytomegalovirus and HIV. May occasionally follow vaccination.

Differential diagnosis is extensive and includes myasthenia gravis, poliomyelitis, porphyria, lead and solvent poisoning, botulism and other causes of peripheral neuropathy.

– turning/nursing care/physiotherapy.

– prompt treatment of infection, e.g. urinary, respiratory.

– appropriate treatment of haemodynamic abnormalities.

– respiratory: close monitoring of vital capacity; 15 ml/kg is usually taken as the minimum before IPPV is instituted, together with other features of respiratory failure. However, earlier tracheal intubation may be necessary if bulbar failure coexists. Tracheostomy is often necessary since prolonged respiratory support may be required.

immunoglobulin therapy (IVIg) is now the specific treatment of choice: 0.4 g/kg/day iv over 3–5 days (see Immunoglobulins, intravenous).

immunoglobulin therapy (IVIg) is now the specific treatment of choice: 0.4 g/kg/day iv over 3–5 days (see Immunoglobulins, intravenous).

plasmapheresis is equally effective as IVIg at speeding recovery and is most beneficial if performed within the first 2 weeks, and before ventilatory support is required. Usually performed daily for 4–5 days. Combining plasmapheresis and IVIg has no additional benefit.

plasmapheresis is equally effective as IVIg at speeding recovery and is most beneficial if performed within the first 2 weeks, and before ventilatory support is required. Usually performed daily for 4–5 days. Combining plasmapheresis and IVIg has no additional benefit.

corticosteroids have no role.

corticosteroids have no role.

CSF filtration has been used occasionally in severe, resistant cases.

CSF filtration has been used occasionally in severe, resistant cases.

GVHD, see Graft-versus-host disease