chapter 15

Further Reading, Keeping Up-to-date and Retrieving Information

It was not intended for this textbook to be a comprehensive discussion of neurology, but rather to put down on paper the simple concepts that have been developed over more than 30 years of teaching. The aim has always been to make the learning (and the practice) of clinical neurology more interesting and less intimidating for the non-neurologist (medical students, hospital medical officers, physician trainees, general physicians and general practitioners). Most of the chapters have been written from a symptom rather than a disease oriented approach and have discussed the more commonly encountered neurological disorders.

KEEPING UP-To-Date

The amount of information available to the clinician is mindboggling. Typing the word ‘stroke’ into Google retrieves 49,000,000 hits! This is reduced to 1,580,000 for Google Scholar and 145,200 in PubMed. This has been referred to as ‘information overload’ [1].

As Glasziou pointed out, only 1 in 18 articles fulfil evidence-based medicine criteria, indicating that for the uninitiated there are vast numbers of potentially misleading papers in the literature. There are a number of books [2, 3]2 and articles in journals [4–23] that discuss how to read the medical literature. Unfortunately, most medical practitioners never acquire the skills or have the time to read journal articles thoroughly. Most rely on information from colleagues, pharmaceutical company representatives, clinical scientific and education meetings, review articles and resources such as the online subscription service ‘up-to-date’ (http://www.uptodate.com/home/index.html) to try and keep their knowledge current.

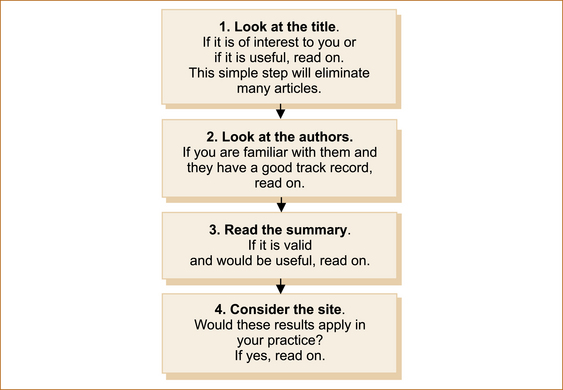

The McMaster group devised a simple and effective strategy for filtering papers [24]. They suggested the approach illustrated in Figure 15.1.

The next step depends on the nature of the paper:

• Diagnostic test. Was there an independent ‘blind’ comparison with a ‘gold standard’ of diagnosis?

• Clinical course and prognosis. Was there an ‘inception cohort’?3

• Determining aetiology. Were the basic methods used to study causation strong?

• Distinguishing useful from useless or harmful therapy. Was the assignment of patients to treatments really randomised?4

Another useful technique is to peruse the contents page of a journal for articles of interest, particularly those that have an associated editorial. In particular, the three major journals, the British Medical Journal, the Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine, may be scanned in this way to retrieve neurology-related and other articles of interest. The clinicopathological conferences in the New England Journal of Medicine are a wonderful source of information.5

Perhaps the most effective method of gaining new knowledge is retrieving information about a particular problem that you are dealing with at that time. Ready access to the Internet makes it possible to find relevant papers even during a consultation with the patient, e.g. when you wish to give the patient additional information. The Internet can help sort out a difficult diagnostic problem such as that discussed in Chapter 6, ‘After the history and examination, what next?’ Most frequently, the question that arises relates to the latest diagnostic test or criteria for a particular entity or the optimal treatment for a particular condition. It is not possible to retrieve and evaluate all this information at the time of consultation. A suggestion is to review the literature on a particular disease on a regular basis, adding to your database of knowledge by retaining the previous reviews.

A major problem is the growing number of institutions and companies vying to provide online information. It is almost impossible to choose between them. In essence all these entities are retrieving the same literature and trying to put it into a digestible form. It is suggested that you sample a few and find one that meets your needs before committing to a subscription.

RETRIEVING USEFUL INFORMATION FROM THE INTERNET

Entrez–PubMed is the database used by most clinicians. A more detailed description on free-access and biomedical databases other than PubMed can be found in the article by Giglia [25].

Biomed–Central, the open access publisher, maintains a catalogue (http://databases.biomedcentral.com/browsecatalog) of more than 1000 databases. Some databases contain experimental data; others provide synopses of public information; and most are freely accessible. In the subject area there are options to search neurology or neuroscience (http://databases.biomedcentral.com/search), and under the content section the options include disease, experimental data, images, journal articles and links to other sources, to mention only a few.

Evidence-based medicine databases

There are many evidence-based medicine databases, but unfortunately most require payment for access.

• Abstracts can be viewed on the Cochrane review (http://www.cochrane.org/index.htm), but payment is required for the full article.

• Netting the evidence (http://www.shef.ac.uk/scharr/ir/netting) is a British-based website that is intended to facilitate evidence-based healthcare by providing support and access to helpful organisations and useful learning resources, such as an evidence-based virtual library, software and journals. The resources can be browsed by type, and a search facility is available.

• The aim of the Turning research into practice (TRIP) database (http://www.tripdatabase.com) is to allow health professionals to easily find the highest quality material available on the web – to help support evidence-based practice. This is a very interesting and user-friendly tool.

• The QuickClinical (QC) information retrieval system (http://www.chi.unsw.edu.au/chiweb.nsf/page/QuickClinical) is a new type of evidence-access technology that utilises intelligent search filter technology to model typical clinical tasks such as ‘diagnosis’ or ‘prescribing’ to ensure that only the most relevant evidence is retrieved. This means clinicians are more likely to search and, when they do search, are more likely to find information that changes their practice.

• The aim of the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (http://www.cebm.net) is to develop, teach and promote evidence-based health care and provide support and resources to doctors and healthcare professionals to help maintain the highest standards of medicine.

• The National Guideline Clearinghouse™ (NGC) (http://www.ahrq.gov/) is a public resource for evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. NGC is an initiative of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), US Department of Health and Human Services. NGC was originally created by AHRQ in partnership with the American Medical Association and the American Association of Health Plans (now America’s Health Insurance Plans [AHIP]). It also offers synthesis of selected guidelines (http://www.guideline.gov/compare/synthesis.aspx) and expert commentary on issues (http://www.guideline.gov/resources/expert_commentary.aspx).

• Clinicians Health Channel (http://www.hcn.com.au/profiles/shared/component/use/) is sponsored by the Victorian Department of Health and is for the benefit of clinicians working in the Victorian public health sector. It provides access to journals, books, evidence-based practice resources, drug information resources and citation databases.

Searching strategies in PubMed and other search engines

The traditional approach to searching the literature has been with PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), which is a service of the US National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health. It is the integrated, text-based search-and-retrieval system used at The National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) for the major databases, including PubMed, Nucleotide and Protein Sequences, Protein Structures, Complete Genomes, Taxonomy and others.

There are tutorials available for using PubMed (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/disted/pubmed.html). There is also a PDF designed to print and tri-fold (http://nnlm.gov/training/resources/pmtri.pdf).

FINDING PRACTICE GUIDELINES

Once again PubMed allows you to filter articles that are designated practice guidelines.

FINDING THE LATEST INFORMATION ON A PARTICULAR DISEASE

Related references: Another very useful function of PubMed is the related references link. If, as you peruse the initial list of references, you see a particular article that seems to be close to what you want, click the related references (on the right side of the page) and see many other possibly relevant papers.

Exporting references to a reference manager: It is possible to export the references into a reference management program such as Endnotes or Reference Manager. To export to Endnotes the references need to be converted to text files (∗.txt).6 The text file is saved onto the disc. In the Endnotes program go to file and select the import option. Set the import option to ‘PubMed (NLM)’, duplicates to ‘discard duplicates’ and text translation to ‘no translation’. Then simply select ‘import’ and choose the directory where the text file is to be saved. Inside the individual reference you can link to a downloaded PDF.

ALTERNATIVE SEARCH ENGINES USING THE SEMANTIC WEB

GoPubMed: GoPubMed (http://www.gopubmed.org) retrieves PubMed abstracts for your search query and sorts relevant information into categories. It lists the title of the article, and there is the ability to look at the abstract or link to a specific article by selecting the author icon or to go to the journal by selecting the journal icon. This is often useful as it is not uncommon for two or more related articles to be printed in the same volume. Other functions in GoPubMed include:

• What collates abstracts according to the concept hierarchies of GO and MeSH – providing a combined search across the fields of molecular biology and medicine.

• Where provides information about geographic localisation of people, research centres and universities, as well as journals in which retrieved papers were published. The journals are separated into top high impact and more top journals. There is an option to search for a specific journal and to look at reviews only.

• When is the citations time machine. You can see articles published today, last week, last month, last year, during the last 5 years or specify a date.

SearchMedica: This is a great ‘professional medical search’ resource. SearchMedica (http://www.searchmedica.com) is a search engine that scans reputable journals, systematic reviews and evidence-based articles to provide search results. Although SearchMedica displays fewer results than standard search engines, it is accurate, clinically relevant and surprisingly comprehensive. There are options to scan the entire Web or just recommended medical sites and an option to choose mental/nervous system. The limitation is that there are a restricted number of users and it is not always possible to access this website.

Hakia–PubMed: Hakia (http://www.hakia.com) is a true general semantic Web search engine and believes that searchers suffer from information pollution! Hakia semantic technologies have developed a dedicated semantic medical search of PubMed (that has moved away from the popularity-ranked results) to provide credible and relevant search results (http://pubmed.hakia.com/). Credible sites are those that have been vetted by librarians and other information professionals.

Webicina: Webicina (http://www.webicina.com) was designed to help doctors from all the medical specialties, and patients as well, to get closer to the Web 2.0-based world. E-patients are tech-savvy members of the community trying to find reliable medical information on the web who want to communicate with their doctors via e-mail or skype and store their medical files online. The number of e-patients is growing rapidly while the number of web-savvy doctors is not.

GENERAL NEUROLOGY WEBSITES

• Cochrane Collaboration (http://www.cochrane.org/index.htm). The aim of the Cochrane Collaboration is improving healthcare decision making globally, through systematic reviews of the effects of healthcare interventions. Unfortunately, many reviews conclude that there is insufficient evidence and that further studies are needed.

• European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS) (http://www.efns.org/content_old.php?myaction=viewsub-1-1-6). The EFNS represents the national neurological societies of 40 European countries.

• Internet Drug Index (http://www.rxlist.com/). This provides an alphabetical list of drugs, a pill identifier and an explanation of diseases, conditions and tests.

• World Federation of Neurology (WFN) (http://www.wfneurology.org/). The WFN is the international body representing the specialty of neurology in more than 100 countries/regions of the globe. The WFN has these neurological societies as its members, and their individual members are in turn WFN members through the association. The purpose of the WFN is to improve human health worldwide by promoting prevention and the care of persons with disorders of the entire nervous system by:

COUNTRY-BASED NEUROLOGY WEBSITES

European websites

• European Federation of Neurological Societies, http://www.efns.org/content_old.php?myaction=viewsub-1-1-6# (This URL will link to the neurological societies of 40 countries.)

Asia and Pacific websites

• Asia ASEAN Neurological Association, http://www.asean-neurology.org/

• Australian and New Zealand Association of Neurologists, http://www.anzan.org.au/index.asp

• Hong Kong Neurological Society, http://www.ns.org.hk/

• Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology, http://www.jspn.or.jp/english/index.html

• Korean Neurological Association, http://www.neuro.or.kr/eng/

• Malaysian Society of Neurosciences, http://www.neuro.org.my/

• Neurological Society of India, http://www.neurosocietyindia.com/

• Neurological Society of Thailand, http://thaineurology.com/index.html

• Pakistan Neurological Society, http://www.pakns.org/

• Philippine Neurological Association, http://www.pna.org.ph/

• Singapore Clinical Neuroscience Society, http://cnssingapore.blogspot.com/

WEBSITES RELATED TO THE MORE COMMON NEUROLOGICAL PROBLEMS

The following are very useful and readily accessible resources.

• The National Institutes of Health has a website (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) dedicated to clinical trials that has in excess of 70,000 registered trials. These can be searched by topic and country, e.g. headache, stroke etc. The website comments on whether the trial is recruiting or not and whether completed. Links are provided to the most up-to-date information, including when the results have been published linked to abstracts on PubMed.

• It also has a website dedicated to neurological disorders listed alphabetically (http://www.ninds.nih.gov/index.htm).

• There is a section dedicated to patient resources also listed alphabetically (http://www.ninds.nih.gov/find_people/voluntary_orgs/organizations_index.htm).

Cerebral vascular disease

• American Stroke Association, http://www.strokeassociation.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=1200037

• Stroke Trials Registry, http://www.strokecenter.org/trials/

• Washington University Internet Stroke Centre, http://www.strokecenter.org/prof/

• Cochrane Library Stroke Reviews, http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/topics/93_reviews.html

Epilepsy

• International General Epilepsy Sites, http://www.epinet.org.au

• International League against Epilepsy, http://www.ilae-epilepsy.org/

• Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, http://www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/70/index.html; PDF version, http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign70.pdf

• American Epilepsy Society, http://www.aesnet.org/

• Epilepsy Society of Australia, http://www.epilepsy-society.org.au/pages/index.php, http://www.epilepsyaustralia.org/

EPILEPSY TREATMENT GUIDELINES

• American Epilepsy Society Guidelines and Practice Parameters, http://www.aesnet.org/go/practice/guidelines/guidelines-and-practice-parameters

• American Academy of Neurology Practice Guidelines on the Use of Newer Seizure Medicines in New Onset Epilepsy, http://aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/patient_ep_onset_c.pdf

• Practice Guideline on the Use of the Newer Seizure Medicines in Refractory Epilepsy, http://aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/patient_ep_refract_c.pdf

AVAILABLE TREATMENTS FOR REFRACTORY EPILEPSY

• American Academy of Neurology Treatments for Patients with Refractory Epilepsy, http://aan.com/professionals/practice/pdfs/patient_ep_treatment_b.pdf

• Canada-Ontario New Epilepsy Treatment Guidelines, http://www.epilepsyontario.org/client/EO/EOWeb.nsf/web/New+Epilepsy+Treatment+Guidelines

• National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (UK), http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=byID&r=true&o=10954

Headache

• American Headache Society, http://www.achenet.org/resources/information/index.asp

• The Migraine Trust, http://www.migrainetrust.org

• The National Headache Foundation, http://www.headaches.org

• National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/migraine/migraine.htm

Parkinson’s and movement disorders

MAJOR NEUROLOGY JOURNAL WEBSITES

The most significant website is of course PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?db=pubmed), supported by the US National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health in the USA.

Specific neurology journal websites

The journals marked with an asterisk (∗) were rated as the top 5 in a questionnaire of members of the World Federation of Neurology [26].

• Acta Neurologica Scandinavica (Sweden), http://www.wiley.com/bw/journal.asp?ref=0001-6314&site=1

• Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology (India), http://www.annalsofian.org/

• Annals of Neurology∗ (USA), http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/76507645/home?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0

• Archives of Neurology (USA), http://archneur.ama-assn.org/

• Brain∗ (UK), http://brain.oxfordjournals.org/

• Cerebrovascular Diseases, http://www.online.karger.com/ProdukteDB/produkte.asp?Aktion=JournalHome&ProduktNr=224153

• Chinese Journal of Cerebrovascular Diseases, http://chinanew.eastview.com/kns50/Navi/item.aspx?NaviID=1&BaseID=NXGB&NaviLink=%e4%b8%ad%e5%9b%bd%e8%84%91%e8%a1%80%e7%ae%a1%e7%97%85%e6%9d%82%e5%bf%97

• Chinese Journal of Neurology, http://zhsjk.periodicals.net.cn/ http://chinanew.eastview.com/kns50/Navi/item.aspx?NaviID=1&BaseID=ZHSJ&NaviLink=%e4%b8%ad%e5%8d%8e%e7%a5%9e%e7%bb%8f%e7%a7%91%e6%9d%82%e5%bf%97

• Epilepsia (USA), http://www.wiley.com/bw/journal.asp?ref=0013-9580

• European Journal of Neurology, http://www.wiley.com/bw/journal.asp?ref=1351-5101

• Headache (USA), http://www.wiley.com/bw/journal.asp?ref=0017-8748

• Journal of Clinical Neuroscience (Australia), http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/623056/description#description

• Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry (UK), http://jnnp.bmj.com/

• Journal of the Neurological Sciences (USA), http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/506078/description#description

• Journal für Neurologie, Neurochirurgie und Psychiatrie (Austria), http://www.kup.at/journals/neurologie/index.html

• Journal of Neurotrauma∗ (USA), http://www.liebertpub.com/products/product.aspx?pid=39

• Movement Disorders (USA), http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/76507419/home

• Multiple Sclerosis (USA), http://msj.sagepub.com/

• Neurology∗ (USA), http://www.neurology.org/

• Neurology Asia, http://neurologyasia.org/journal.php

• Neurology, Neurophysiology and Neuroscience (USA), http://www.neurojournal.com/index

• Pakistan Journal of Neurology, http://www.pakmedinet.com/PJNeuro

RESOURCES FOR PATIENTS

Probably one of the most authoritative is the site sponsored by the United States National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health titled MedlinePlus (http://medlineplus.gov/). MedlinePlus website states that it ‘brings together authoritative information from National Library of Medicine (NLM), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and other government agencies and health-related organisations. Preformulated MEDLINE searches are included in MedlinePlus and give easy access to medical journal articles. MedlinePlus also has extensive information about drugs, an illustrated medical encyclopaedia, interactive patient tutorials, and latest health news. The help topics section links to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke website. It also provides health information in over 40 languages (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/languages/languages.html).

Although this book has primarily been written for students and the non–neurologist, it is also potentially suitable for the neurology trainee in the early stages of training. What follows is a list of books (not in any particular order) that this author has collected and enjoyed reading. Many have been useful resources to which he has constantly referred.

Gray’s Anatomy, 40th edn, Susan Standring, Churchill Livingstone. This is a book that one refers to when very detailed neuroanatomy is required.

Mechanism and Management of Headache. 7th edn, J Lance, PJ Goadsby, Elsevier Butterworth–Heinemann, 2004. One of those books to which you will constantly refer.

Aids to the Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System, 4th edn, Brain, WB Saunders Company, 2000. This is a thin paperback book that should be on every desktop. It shows how to examine each muscle, the nerve and nerve root supply and contains excellent illustrations of the individual nerves supplying muscles, the sensory supply to the skin of the nerves and the nerve roots (dermatomes).

Seizures and Epilepsy, J Engel, Jr, FA Davis Company, 1989. An excellent clinical textbook on the subject of epilepsy.

The Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma, Fred Plum, Jerome Posner, Oxford University Press, 2007. One of the neurological classics with a superb description of how to examine the comatose patient and how to use those findings to establish the cause of the coma.

Neurological Aspects of Substance Abuse, 2nd edn, JCM Brust, Elsevier Butterworth–Heinemann, 2004. An excellent reference source for dealing with patients admitted with complications from using recreational drugs.

Cerebrospinal Fluid in Diseases of the Nervous System, 2nd edn, RA Fishman, WB Saunders Company, 1992. An invaluable resource to check the cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in particular diseases.

McAlpine’s Multiple Sclerosis, 1st edn, WB Matthews, ED Acheson, JR Batchelor, RO Weller, Churchill Livingstone, 1985.

McAlpine’s Multiple Sclerosis, 4th edn, A Compstan, I McDonald, J Noseworthy, H Lassmnaa, D Miller, K Smith, H Wekerle, C Confravreux, Churchill Livingstone, 2005. Both these books are excellent resources on multiple sclerosis.

Neurological Complications of Therapy, A Silverstein (ed), Futura Publishing Company, 1982. Although old nothing has been written that has replaced it. This book has excellent chapters on the neurological complications of chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Principles and Practice of Movement Disorders, S Fahn S, J Jankovic, Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier, 2007. Written by two world experts who have clearly seen many patients with movement disorders. Described by a colleague with subspecialty interest in this area as the best book he has ever read on the subject.

Neurological Complications of Renal Disease, CF Bolton, GB Young, Butterworth Publishers, 1990. An excellent description of the neurological complications of renal disease.

Handbook of Neurologic Rating Scales, RM Herndon (ed), Demos Vermande, 1997. Describes and discusses the neurological rating scales applicable to many disorders of the nervous system.

Primer on the Autonomic Nervous System, D Robertson, I Biaggioni, G Burnstock, PA Low, Elsevier Academic Press, 2004. This has been written by one of the world’s authorities on the autonomic nervous system.

AIDS and the Nervous System, 1st edn, ML Rosenblum, RM Levy, DE Bresdesen, Raven Press, 1988; 2nd edn, JR Berger, RM Levy, 1997. Excellent description of the approach to the patient with AIDS and neurological symptoms.

The Clinical Practice of Critical Care Neurology, E Wijdicks, Oxford University Press, 2003. An excellent book to aid the neurologist who is called upon to see patients in the intensive care unit.

Neurologic Catastrophes in the Emergency Department, E Wijdicks, Butterworth–Heinemann, 1999. A useful book for every neurologist attached to a hospital who has to attend the accident and emergency department.

Infectious Diseases of the Central Nervous System, KL Tyler, JB Martin, (Contemporary Neurology Series), FA Davis Co., 1993.

Posterior Circulation Disease: Clinical Findings, Diagnosis, and Management, LR Kaplan, Blackwell Science, 1996.

Peripheral Neuropathy, 4th edn, P Dyck, PK Thomas (eds), Elsevier Saunders, 2005.

The Treatment of Epilepsy – Principles and Practice, 3rd edn, E Wyllie (ed), Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

Cranial Neuroimaging and Clinical Neuroanatomy, H-J Kretschmann, W Weinrich, Georg Thieme Verlag, 2004.

Handbook of Epilepsy Treatment, 2nd edn, SD Shorvon, Blackwell Science, 2005.

Handbook of Clinical Neurology, PJ Vinken, GW Bruyn, HL Klawans (eds), Elsevier, 1986. This is the encyclopaedia of clinical neurology, currently into the revised edition. Each chapter is very detailed and a good place to look for those neurological oddities. (An example is the patient with severe muscle hypertrophy such that he was bursting out of his clothes. This author consulted the handbook and was able to find the cause of the patient’s problem: it was hypothyroidism.)

Neurology in Clinical Practice, W Bradley et al, Butterworth–Heinemann

Practical Neurology, J Biller, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins

Textbook of Clinical Neurology, C Goetz, WB Saunders Company

Merritt’s Neurology, RL Lewis, HH Merritt, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins

Harrison’s Neurology in Clinical Practice, S Hauser, McGraw Hill

Neurological Differential Diagnosis, J Patten, Springer–Verlag

Adams and Victor’s Manual of Neurology, 7th edn, M Victor, AH Ropper, McGraw–Hill

Introductory Neurology, JG McLeod, JW Lance, L Davies, Blackwell Science

REFERENCES

1. Glasziou, P.P. Information overload: What’s behind it, what’s beyond it? Med J Aust. 2008;189(2):84–85.

2. Greenhalgh, T. How to read a paper: The basics of evidence based medicine, 2nd edn. London: BMJ Books; 2001.

3. Sackett, D.L., et al. Evidence-based medicine: How to practise and teach EBM. Toronto: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

4. Richardson, W.S., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIV. How to use an article on the clinical manifestations of disease. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284(7):869–875.

5. Giacomini, M.K., Cook, D.J. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B. What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284(4):478–482.

6. Giacomini, M.K., Cook, D.J. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284(3):357–362.

7. McGinn, T.G., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXII. How to use articles about clinical decision rules. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284(1):79–84.

8. Hunt, D.L., Jaeschke, R. McKibbon KA. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXI. Using electronic health information resources in evidence-based practice. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;283(14):1875–1879.

9. Bucher, H.C., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XIX. Applying clinical trial results. A. How to use an article measuring the effect of an intervention on surrogate end points. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1999;282(8):771–778.

10. Randolph, A.G., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XVIII. How to use an article evaluating the clinical impact of a computer-based clinical decision support system. JAMA. 1999;282(1):67–74.

11. Barratt, A., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XVII. How to use guidelines and recommendations about screening. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1999;281(21):2029–2034.

12. Guyatt, G.H., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XVI. How to use a treatment recommendation. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group and the Cochrane Applicability Methods Working Group. JAMA. 1999;281(19):1836–1843.

13. Richardson, W.S., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XV. How to use an article about disease probability for differential diagnosis. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1999;281(13):1214–1219.

14. Dans, A.L., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XIV. How to decide on the applicability of clinical trial results to your patient. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1998;279(7):545–549.

15. O’Brien, B.J., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XIII. How to use an article on economic analysis of clinical practice. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1997;277(22):1802–1806.

16. Drummond, M.F., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XIII. How to use an article on economic analysis of clinical practice. A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1997;277(19):1552–1557.

17. Guyatt, G.H., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XII. How to use articles about health-related quality of life. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1997;277(15):1232–1237.

18. Naylor, C.D., Guyatt, G.H. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XI. How to use an article about a clinical utilization review. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1996;275(18):1435–1439.

19. Naylor, C.D., Guyatt, G.H. Users’ guides to the medical literature: X. How to use an article reporting variations in the outcomes of health services. The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1996;275(7):554–558.

20. Guyatt, G.H., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1995;274(22):1800–1804.

21. Wilson, M.C., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: VIII. How to use clinical practice guidelines. B. what are the recommendations and will they help you in caring for your patients? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1995;274(20):1630–1632.

22. Hayward, R.S., et al. Users’ guides to the medical literature: VIII. How to use clinical practice guidelines. A. Are the recommendations valid? The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1995;274(7):570–574.

23. Richardson, W.S., Detsky, A.S. Users’ guides to the medical literature: VII. How to use a clinical decision analysis. B. What are the results and will they help me in caring for my patients? Evidence Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1995;273(20):1610–1613.

24. Sackett, D.L., Haynes, R.B., Tugwell, P. Clinical epidemiology: A basic science for clinical medicine. Little, Brown; 1985. [370].

25. Giglia, E. Beyond PubMed. Other free-access biomedical databases. Eur Medicophys. 2007;43(4):563–569.

26. Yue, W., Wilson, C.S., Boller, F. Peer assessment of journal quality in clinical neurology. J Med Libr Assoc. 2007;95(1):70–76.

2A review of ‘How to read a paper’ stated this is one of the bestselling texts on evidence-based medicine, used by healthcare professionals and medical students worldwide. Trisha Greenhalgh’s ability to explain the basics of evidence-based medicine in an accessible and readable way means the book is an ideal introduction for all, from first-year students to experienced practitioners. This is a text that explains the meaning of critical appraisal and terms such as ‘numbers needed to treat’, ‘how to search the literature’, ‘evaluate the different types of papers’ and ‘put the conclusions to clinical use’.

3An inception cohort is where patients are identified at an early and uniform point in the course of the disease.

4If the natural history of a disease is unpredictable, and in particular if spontaneous remission can occur, the only way to assess whether a therapy is of benefit is to randomly allocate half of the patients to the active treatment and the other half to an alternative treatment or to a placebo.

5The technique in this paragraph is used by the author who finds it an excellent method of keeping abreast of recent developments.

6In 2009 PubMed altered the way files are handled. Currently on the right side of the page is a ‘Send To’ tab; click on this, choose ‘File’ (there are other options such as ‘Clipboard’, ‘E-mail’, ‘Collections’ and ‘Order’) and then select ‘Medline’ under format. It is possible to sort the references by recently added, first author, last author, journal, publication date or title using the ‘Sort By’ tab. Selecting ‘Create file’ brings up another dialogue box asking if you wish to save or open the file; select ‘Save’ and save the file pubmed_result.txt into the relevant directory on your computer.