Chapter 2 Functional Medicine

A Twenty-First Century Model of Patient Care and Medical Education

What is Functional Medicine?

What is Functional Medicine?

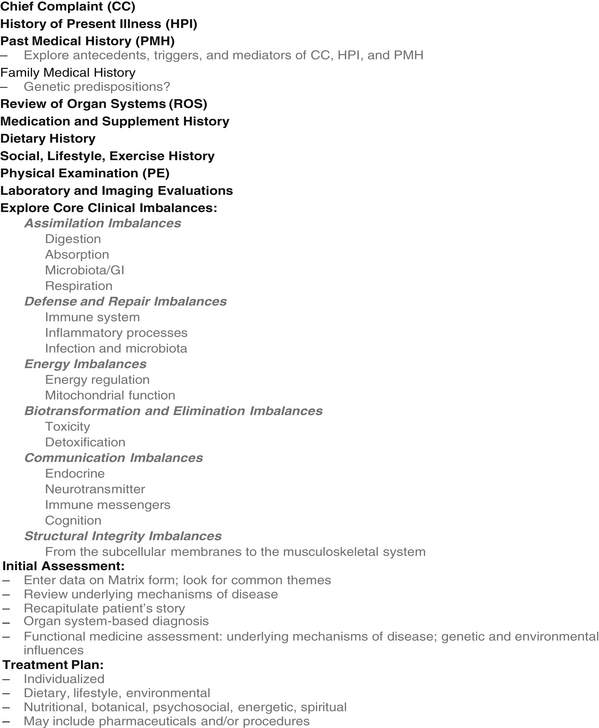

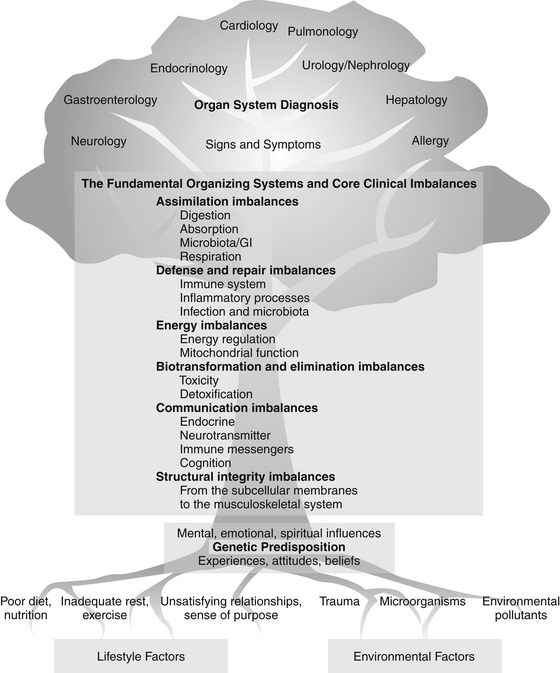

One way to conceptualize where functional medicine falls in the continuum of health and health care is to examine the functional medicine “tree.” In its approach to complex chronic disease, functional medicine encompasses the whole domain represented by the graphic shown in Figure 2-1, but first addresses the patient’s core clinical imbalances (found in the functional physiologic organizing systems), the fundamental lifestyle factors that contribute to chronic disease, and the antecedents, triggers, and mediators that initiate and maintain the disease state. Diagnosis, of course, is part of the functional medicine model, but the emphasis is on understanding and improving the functional core of the human being as the starting point for intervention.

FIGURE 2-1 The continuum of health and health care: the functional medicine tree.

(Courtesy of the Institute for Functional Medicine.)

Functional medicine clinicians focus on restoring balance to the dysfunctional systems by strengthening the fundamental physiologic processes that underlie them and by adjusting the environmental and lifestyle inputs that nurture or impair them. This approach leads to therapies that focus on restoring health and function, rather than simply controlling signs and symptoms.

Principles

Seven basic principles characterize the functional medicine paradigm:

• Acknowledging the biochemical individuality of each human being, based on the concepts of genetic and environmental uniqueness

• Incorporating a patient-centered rather than a disease-centered approach to treatment

• Seeking a dynamic balance among the internal and external factors in a patient’s body, mind, and spirit

• Addressing the web-like interconnections of internal physiologic factors

• Identifying health as a positive vitality—not merely the absence of disease—and emphasizing those factors that encourage a vigorous physiology

• Promoting organ reserve as a means of enhancing the health span, not just the life span, of each patient

• Staying abreast of emerging research—a science-using approach

Lifestyle and Environmental Factors

The building blocks of life, as well as the primary influences on them, are found at the base of the functional medicine tree graphic (see Figure 2-1). When we talk about influencing gene expression, we are interested in the interaction between lifestyle and environment in the broadest sense and any genetic predispositions with which a person may have been born—including the epigenome.* Many environmental factors that affect genetic expression are (or appear to be) a matter of choice (such as diet and exercise); others are very difficult for the individual patient to alter or escape (air and water quality, toxic exposures); and still others may be the result of unavoidable accidents (trauma, exposure to harmful microorganisms). Some factors that may appear modifiable are heavily influenced by the patient’s economic status—if you are poor, for example, it may be impossible to choose more healthful food, decrease stress in the workplace and at home, or take the time to exercise and rest properly. Existing health status is also a powerful influence on the patient’s ability to alter environmental input. If you have chronic pain, exercise may be extremely difficult; if you are depressed, self-activation is a major challenge.

The influence of these lifestyle and environment factors on the human organism is indisputable,1,2 and they are often powerful agents in the battle for health. Ignoring them in favor of the quick fix of writing a prescription—whether for pharmaceutical agents, nutraceuticals, or botanicals—means the cause of the underlying dysfunction may be obscured but not eliminated. In general terms, the following factors should be considered when working to reverse dysfunction or disease and restore health:

• Diet (type, quality, and quantity of food; food preparation; calories, fats, proteins, carbohydrates)

• Nutrients (both dietary and supplemental)

• Microorganisms (and the general condition of the soil in which food is grown)

• Psychosocial and spiritual factors, such as meaning and purpose, relationships, work, community, economic status, stress, and belief systems

Fundamental Physiologic Processes

These fundamental physiologic processes are usually taught early in health professions curricula, where they are appropriately presented as the foundation of modern, scientific patient care. Unfortunately, subsequent training in the clinical sciences often fails to fully integrate knowledge of the functional mechanisms of disease with therapeutics and prevention, emphasizing organ system diagnosis instead.3 Focusing predominantly on organ system diagnosis without examining the underlying physiology that produced the patient’s signs, symptoms, and disease often leads to managing patient care by matching diagnosis to pharmacology. The job of the health care provider then becomes a technical exercise in finding the drug or procedure that best fits the diagnosis (not necessarily the patient), leading to a significant curtailment of critical thinking pathways: “Medicine, it seems, has little regard for a complete description of how myriad pathways result in any clinical state.”4

Even more important, pharmacologic treatments (and even natural remedies) are often prescribed without careful consideration of their physiologic effects across all organ systems, physiologic processes, and genetic variations.5 Pharmaceutical companies exploit this weakness. We do not see drug advertisements that urge the practitioner to carefully consider the impact of all other drugs being taken by the patient before prescribing a new one! The marketing of drugs to specific specialty niches, and the use of sound bite sales pitches that suggest discrete effects, skews health care thinking toward this narrow, linear logic, as notably exemplified by the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor drugs that were so wildly successful on their introduction, only to be subsequently withdrawn or substantially narrowed in use due to collateral damage.6,7

Core Clinical Imbalances

Biotransformation and Elimination Imbalances

Structural Integrity Imbalances

Using this construct, it becomes much clearer that one disease and/or condition may have multiple causes (i.e., multiple clinical imbalances), just as one fundamental imbalance may be at the root of many seemingly disparate conditions (Figure 2-2).

Antecedents, Triggers, and Mediators*

Triggers and the Provocation of Illness

Common triggers include physical or psychic trauma, microbes, drugs, allergens, foods (or even the act of eating or drinking), environmental toxins, temperature change, stressful life events, adverse social interactions, and powerful memories. For some conditions, the trigger is such an essential part of our concept of the disease that the two cannot be separated; the disease is either named after the trigger (e.g., strep throat) or the absence of the trigger negates the diagnosis (e.g., concussion cannot occur without head trauma). For chronic ailments like asthma, arthritis, or migraine headaches, multiple interacting triggers may be present. All triggers, however, exert their effects through the activation of host-derived mediators. In closed-head trauma, for example, activation of N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors, induction of nitric oxide synthase, and liberation of free intraneuronal calcium determine the late effects. Intravenous magnesium at the time of trauma attenuates severity by altering the mediator response.8,9 Sensitivity to different triggers often varies among persons with similar ailments. A prime task of the functional practitioner is to help patients identify important triggers for their ailments and develop strategies for eliminating them or diminishing their virulence.

Mediators and the Formation of Illness

A mediator is anything that produces symptoms or damages tissues of the body, including certain behaviors. Mediators vary in form and substance. They may be biochemical (e.g., prostanoids and cytokines), ionic (e.g., hydrogen ions), social (e.g., reinforcement for staying ill), psychological (e.g., fear), or cultural (e.g., beliefs about the nature of illness). A list of common mediators is presented in Box 2-1. Illness in any single person usually involves multiple interacting mediators. Biochemical, psychosocial, and cultural mediators interact continuously in the formation of illness.

Constructing the Model

Constructing the Model

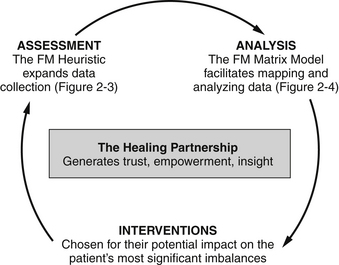

Assessment

Combining the principles, lifestyle and environment factors, fundamental physiologic processes, antecedents, triggers, mediators, and core clinical imbalances creates a new information gathering and sorting architecture for clinical practice—in effect a new heuristic* to serve the practice of functional medicine. This new model includes an explicit emphasis on principles and mechanisms that infuse meaning into the diagnosis and deepen the clinician’s understanding of the often overlapping ways things go wrong. Any methodology for constructing a coherent story and an effective therapeutic plan in the context of complex chronic illness must be flexible and adaptive. Like an accordion file that compresses and expands upon demand, the amount and kind of data collected will necessarily change in accordance with the patient’s situation and the clinician’s time and ability to piece together the underlying threads of dysfunction.

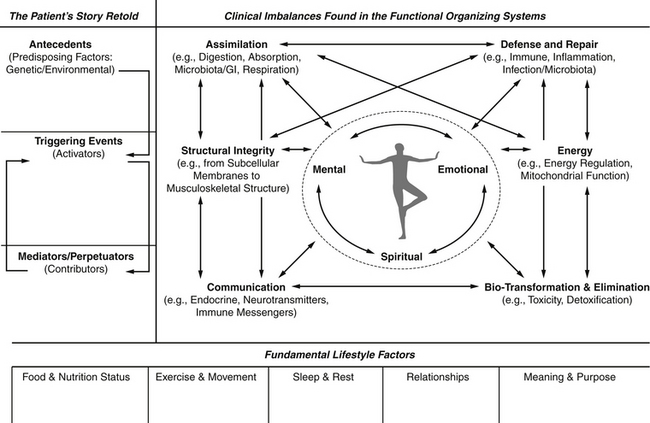

The conventional assessment process involving the Chief Complaint, History of Present Illness, and Past Medical History sections must be expanded (Figure 2-3) to include a thorough investigation of antecedents, triggers, and mediators, and a systematic evaluation of any imbalances within the fundamental organizing systems. Personalized medical care without this expanded investigation falls short.

The Functional Medicine Matrix Model

Distilling the data from the expanded history, physical examination, and laboratory findings into a narrative story line that includes antecedents, triggers, and mediators can be challenging. Key to developing a thorough narrative is organizing the story using the Functional Medicine Matrix Model form (Figure 2-4).

FIGURE 2-4 The functional medicine matrix model.

(Courtesy of the Institute for Functional Medicine.)

• Indicators of inflammation on the matrix might lead the clinician to request tests for specific inflammatory markers (such as highly sensitive C-reactive protein, interleukin levels, and/or homocysteine).

• Essential fatty acid levels, methylation pathway abnormalities, and organic acid metabolites help determine adequacy of dietary and nutrient intakes.

• Markers of detoxification (glucuronidation and sulfation, cytochrome P450 enzyme heterogeneity) can determine functional capacity for molecular biotransformation.

• Neurotransmitters and their metabolites (vanilmandelate, homovanillate, 5-hydroxyindoleacetate, quinolinate) and hormone cascades (gonadal and adrenal) have obvious utility in exploring messenger molecule balance.

• Computed tomographic scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or plain x-rays extend the view of the patient’s structural dysfunctions. The use of bone scans, dual energy x-ray absorptiometry scans, or bone resorption markers10,11 can be useful in further exploring the web-like interactions of the matrix.

• Newer, useful technologies such as functional MRIs, single-photon emission computed tomography or positron emission tomographic scans offer more comprehensive assessment of metabolic function within organ systems.

1. Whole body interventions: Because the human organism is a complex adaptive system, with countless points of access, interventions at one level will affect points of activity in other areas as well. For example, improving the patient’s sleep beneficially influences the immune response, melatonin levels, and T-cell lymphocyte levels and helps decrease oxidative stress. Exercise reduces stress, improves insulin sensitivity, and improves detoxification. Reducing stress (and/or improving stress management) reduces cortisol levels, improves sleep, improves emotional well being, and reduces the risk of heart disease. Changing the diet has myriad effects on health, from reducing inflammation to reversing coronary artery disease.

2. Organ system interventions: These interventions are used more frequently in the acute presentation of illness. Examples include splinting; draining lesions; repairing lacerations; reducing fractures, pneumothoraxes, hernias, or obstructions; or removing a stone to reestablish whole organ function. There are many interventions that improve organ function. For example, bronchodilators improve air exchange, thereby decreasing hypoxia, reducing oxidative stress, and improving metabolic function and oxygenation in a patient with reactive airway disease.

3. Metabolic or cellular interventions: Cellular health can be addressed by insuring the adequacy of macronutrients, essential amino acids, vitamins, and cofactor minerals in the diet (or, if necessary, from supplementation). An individual’s metabolic enzyme polymorphisms can profoundly affect his or her nutrient requirements. For example, adding conjugated linoleic acid to the diet can alter the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor system, affect body weight, and modulate the inflammatory response.12–14 However, in a person who is diabetic or insulin resistant, adding conjugated linoleic acid may induce hyperproinsulinemia, which is detrimental.15,16 Altering the types and proportions of carbohydrates in the diet may increase insulin sensitivity, reduce insulin secretion, and fundamentally alter metabolism in the insulin-resistant patient. Supporting liver detoxification pathways with supplemental glycine and N-acetylcysteine improves the endogenous production of adequate glutathione, an essential antioxidant in the central nervous system and gastrointestinal tract.

4. Subcellular/mitochondrial interventions: There are many examples of nutrients that support mitochondrial function.17,18 Inadequate iron intake causes oxidants to leak from mitochondria, damaging mitochondrial function and mitochondrial DNA. Making sure there is sufficient iron helps alleviate this problem. Inadequate zinc intake (found in more than 10% of the U.S. population) causes oxidation and DNA damage in human cells.18 Ensuring the adequacy of antioxidants and cofactors for the at-risk individual must be considered in each part of the matrix. Carnitine, for example, is required as a carrier for the transport of fatty acids from the cytosol into the mitochondria, improving the efficiency of β-oxidation of fatty acids and resultant adenosine triphosphate production. In patients who have lost significant weight, carnitine undernutrition can result in fatty acids undergoing ω-oxidation, a far less efficient form of metabolism.19 Patients with low carnitine may also respond to riboflavin supplementation.19

5. Subcellular/gene expression interventions: Many compounds interact at the gene level to alter cellular response, thereby affecting health and healing. Any intervention that alters nuclear factor-κB entering the nucleus, binding to DNA, and activating genes that encode inflammatory modulators, such as interleukin-6 (and thus C-reactive protein), cyclooxygenase-2, interleukin-1, lipoxygenase, inducible nitric oxide synthase, tumor necrosis factor-α, or a number of adhesion molecules, will impact many disease conditions.20,21 There are many ways to alter the environmental triggers for nuclear factor-κB, including lowering oxidative stress, altering emotional stress, and consuming adequate phytonutrients, antioxidants, alpha-lipoic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, and γ-linoleic acid.20 Adequate vitamin A allows the appropriate interaction of vitamin A-retinoic acid with more than 370 genes.22 Vitamin D in its most active form intercalates with a retinol protein and the DNA exon and modulates many aspects of metabolism, including cell division in both healthy and cancerous breast, colon, prostate, and skin tissue.23 Vitamin D has key roles in controlling inflammation, calcium homeostasis, bone metabolism, cardiovascular and endocrine physiology, and healing.23

The Healing Partnership

No discussion of the functional medicine model would be complete without mention of the therapeutic relationship. Partnerships are formed to achieve an objective. For example, a business partnership forms to engage in commercial transactions for financial gain; a marriage partnership forms to build a caring, supportive, home-centered environment. A healing partnership forms to heal the patient through the integrated application of both the art of medicine (insight driven) and the science of medicine (evidence driven). An effective partnership requires that trust and rapport be established. Patients must feel comfortable telling their stories and revealing intimate information and significant events.

Contemporary medicine considers the wholeness of healing to be beyond its orthodoxy—the domain of the nonscientific and nonmedical.24 We disagree. To grasp the profound importance of the healing partnership to the creation of a system of medicine adequate to the demands of the twenty-first century, an emerging body of relevant research was reviewed.25–27 As Louise Acheson, MD, MS, Associate Editor for the Annals of Family Practice, articulated recently in that journal28.

It is challenging to research this ineffable process called healing…. Hsu and colleagues asked focus groups of nurses, physicians, medical assistants, and randomly selected patients to define healing and describe what facilitates or impedes it.30 The groups arrived at surprisingly convergent definitions: “Healing is a dynamic process of recovering from a trauma or illness by working toward realistic goals, restoring function, and regaining a personal sense of balance and peace.” They heard from diverse participants that “healing is a journey” and “relationships are essential to healing.”

Research into the role of healing in the medical environment recently generated some thoughtful and robust investigations. Scott et al’s25 research into the healing relationship found very similar descriptions to those of Hsu et al.29 The participants in the study26 articulated aspects of the healing partnership as:

1. Valuing and creating a nonjudgmental emotional bond

2. Appreciating power and consciously managing clinician power in ways that would most benefit the patient

3. Abiding and displaying a commitment to caring for patients over time

Three relational outcomes result from these processes: trust, hope, and a sense of being known. Clinician competencies that facilitate these processes are self-confidence, emotional self-management, mindfulness, and knowledge.26 In this rich soil, the healing partnership flourishes.

The characteristics of a conventional therapeutic encounter are fundamentally different from a healing partnership, and each emerges from specific emphases in training. In the therapeutic encounter, the relationship forms to assess and treat a medical problem using (usually) an organ system structure, a differential diagnosis process, and a treatment toolbox focused on pharmacology and medical procedures. The therapeutic encounter pares down the information flow between physician and patient to the minimum needed to identify the organ system domain of most probable dysfunction, followed by a sorting system search (the differential diagnosis heuristic). The purpose of this relationship is to arrive at the most probable diagnosis as quickly as possible and select an intervention based on probable efficacy. The relationship is a left-brain–guided conversation controlled by the clinician and characterized by algorithmic processing and statistical thinking.30,31

In language, we have the fullest expression of the integration of left- and right-brain function. Language is so complex that the brain has to process it in different ways simultaneously—both denotatively and connotatively. For complexity and nuance to emerge in language, the left brain needs to see the trees and the right brain helps us see and understand the forest.32,33

1. Allowing patients to express, without interruption,* their story about why they have come to see you. The manner in which the patient frames the initial complaints often presages later insight into the root causes. Any interruption in this early stage of narrative moves the patient back into left-brain processing and away from insight.34

2. After focusing on the main complaint, encouraging the patient’s narrative regarding their present illness(es). Clarifications can be elicited by further open-ended questioning (e.g., “tell me more about that”; “what else do you think might be going on?”). During this portion of the interview, there is a switching back and forth between right- and left-brain functions.

3. Next, conveying to the patient in the simplest terms possible that to achieve lasting solutions to the problem(s) for which he and/or she has come seeking help, a few fundamental questions must be asked and answered to understand the problem in the context of the patient’s personal life. This framing of the interview process moves the endeavor from a left-brain compilation to a narrative that encourages insight—based on complex pattern recognition—about the root causes of the problem.

4. At this stage, control is shared with the patient: “Without your help, we cannot understand your medical problem in the depth and breadth you deserve.” Implementing this shared investigation can be facilitated by certain approaches:

• Only the patient can inform the partnership about the conditions that provided the soil from which the problem(s) under examination emerged. The patient literally owns the keys to the joint deliberation that can provide insight about the process of achieving a healing outcome.

• The professional brings experience, wisdom, tools, and techniques and works to create the context for a healing insight to emerge.

• The patient’s information, input, mindful pursuit of insight, and engagement become “the horse before the cart.” The cart carries the clinician—the person who guides the journey using evidence, experience, and judgment, and who contributes the potential for expert insight.

The crux of the healing partnership is an equal investment of focus by both clinician and patient. They work together to identify the right places to apply leverage for change. Patients must commit to engage both their left-brain skills and their right-brain function to inform and guide the exploration to the next steps in assessment, therapy, understanding, and insight. Clinicians must also engage both the left-brain computational skills and the right-brain pattern-recognition functions that, when used together, can generate insight about the patient’s story. An overview of the functional medicine model can be seen in Figure 2-5.

Integration of Care

Integration of Care

Functional medicine explicitly recognizes that no single profession can cover all the viable therapeutic options. Interventions and practitioners will differ by training, licensure, specialty focus, and even by beliefs and ethnic heritage. However, all health care disciplines (and all medical specialties) can—to the degree allowed by their training and licensure and assuming a good background in Western medical science—use a functional medicine approach, including integrating the matrix as a basic template for organizing and coupling knowledge and data. Consequently, functional medicine can provide a common language, a flexible architecture, and a unified model to facilitate integrated and integrative care. Regardless of which discipline the clinician has been trained in, developing a network of capable, collaborative practitioners with whom to co-manage challenging patients and to whom referrals can be made for therapies outside the primary clinician’s own expertise will enrich patient care and strengthen the clinician–patient relationship.

1. Goetzel R.Z. Do prevention or treatment services save money? The wrong debate. Health Affairs. 2009;28(1):37–41.

2. Probst-Hensch N.M. Chronic age-related diseases share risk factors: do they share pathophysiological mechanisms and why does that matter? Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140:w13072. Available at http://www.smw.ch/index.php?id=smw-2010-13072 Accessed October, 11, 2010

3. Magid C.S. Developing tolerance for ambiguity. JAMA. 2001;285(1):88.

4. Rees J. Complex disease and the new clinical sciences. Science. 2002;296:698–701.

5. Radford T. Top scientist warns of “sickness” in US health system. BMJ. 2003;326:416. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7386.416/b

6. Vioxx. Lessons for Health Canada and the FDA. CMAJ. 2005;172(11):5.

7. Juni P., Nartey L., Reichenbach S., et al. Risk of cardiovascular events and rofecoxib: cumulative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2004;364:2021–2029.

8. Cernak I., Savic V.J., Kotur J., et al. Characterization of plasma magnesium concentration and oxidative stress following graded traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17(1):53–68.

9. Vink R., Nimmo A.J., Cernak I. An overview of new and novel pharmacotherapies for use in traumatic brain injury. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28(11):919–921.

10. Yu S.L., Ho L.M., Lim B.C., Sim M.L. Urinary deoxypyridinoline is a useful biochemical bone marker for the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1998;27(4):527–529.

11. Palomba S., Orio F., Colao A., et al. Effect of estrogen replacement plus low-dose alendronate treatment on bone density in surgically postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(4):1502–1508.

12. Moya-Camarena S.Y., Vanden Heuvel J.P., Blanchard S.G., et al. Conjugated linoleic acid is a potent naturally occurring ligand and activator of PPARa. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:1426–1433.

13. Gaullier J.M., Halse J., Hoye K., et al. Conjugated linoleic acid supplementation for 1 y reduces body fat mass in healthy overweight humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:1118–1125.

14. O’Shea M., Bassaganya-Riera J., Mohede I.C. Immunomodulatory properties of conjugated linoleic acid. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(S):1199S–1206S.

15. Malloney F., Yeow T.P., Mullen A., et al. Conjugated linoleic acid supplementation, insulin sensitivity, and lipoprotein metabolism in patients with type 2 DM. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(4):887–895.

16. Riserus U., Vessby B., Arner P., Zethelius B. Supplementation with CLA induces hyperproinsulinaemia in obese men: close association with impaired insulin sensitivity. Diabetalogia. 2004;47(6):1016–1019.

17. Ames B.N. The metabolic tune-up: metabolic harmony and disease prevention. J Nutr. 2003;133:1544S–1548S.

18. Ames B.N., Elson-Schwab I., Silver E.A. High-dose vitamin therapy stimulates variant enzymes with decreased coenzyme binding affinity (increased Km): relevance to genetic disease and polymorphisms. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75(4):616–658.

19. Bralley J.A., Lord R.S. Laboratory evaluations in molecular medicine: Nutrients, toxicants and metabolic controls. Atlanta: Institute for Advances in Molecular Medicine; 2001. In Organic acids. 2001:181

20. Yamamoto Y., Gaynor R.B. Therapeutic potential of inhibition of the NF-kB pathway in the treatment of inflammation and cancer. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(2):135–142.

21. Tak P.P., Firestein G.S. NF-kB: a key role in inflammatory disease. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(1):7–11.

22 Balmer J.E., Blomhoff R. Gene expression regulation by retinoic acid. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:1773–1808.

23. Holick M.F. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular diseases. Am J Clin Nutr. 80(Suppl 6), 2004. 1678S-188S

24. Egnew T.R. The meaning of healing: transcending suffering. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):255–262.

25. Scott J.G., Cohen D., DiCicco-Bloom B., et al. Understanding healing relationships in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):315–322.

26. Miller W.L., Crabtree B.F., Duffy M.B., et al. Research guidelines for assessing the impact of healing relationships in clinical medicine. Altern Ther Health Med. 9(3), 2003. (Suppl)A80–A95

27. Jackson C. Healing ourselves, healing others? first in a series. Holist Nurs Pract. 2004;18(2):67–81.

28. Acheson L. Community care, healing, and excellence in research. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:290–291.

29. Hsu C., Phillips W.R., Sherman K.J., et al. Healing in primary care: a vision shared by patients, physicians, nurses, and clinical staff. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(4):307–314.

30. Brown M., Brown G., Sharma S. Evidence-based to value-based medicine. Chicago, IL: AMA Press; 2005. 3-5

31. Sackett D.L., Straus S.E., Richardson W.S., Rosenberg W., Haynes R.B. Evidence-based medicine: how to practice and teach EBM. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000.

32. Fiore S., Schooler J. Right hemisphere contributions to creative problem solving: converging evidence for divergent thinking. In: Beeman M., Chiarello C. Right hemisphere language comprehension: perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. Philadelphia, PA: Erlbaum Publishing; 1998:255–284.

33. Seger C.A., Desmond J.E., Glover G.H., et al. FMRI evidence for right hemisphere involvement in processing unusual semantic relationships. Neuropsychology. 2000;14:361–369.

34. Lehrer J. The annals of science: the eureka hunt. The New Yorker. July 28, 2008:s40–s45.

Galland L., Lafferty H. Gastrointestinal dysregulation: connections to chronic disease. Monograph. Gig Harbor, WA: The Institute for Functional Medicine; 2008.

Hedaya R., Quinn S. Depression: advancing the paradigm. Monograph. Gig Harbor, WA: The Institute for Functional Medicine; 2008.

Jones D.S., ed. Textbook of functional medicine. Gig Harbor, WA: The Institute for Functional Medicine, 2005.

Jones D.S., Hofmann L., Quinn S. 21st century medicine: a new model for medical education and practice. White Paper. Gig Harbor, WA: The Institute for Functional Medicine; 2009.

Liska D., Quinn S., Lukaczer D., et al. Clinical nutrition: a functional approach, 2nd ed. Gig Harbor, WA: The Institute for Functional Medicine; 2004.

Vasquez A. Musculoskeletal pain: expanded clinical strategies. Monograph. Gig Harbor, WA: The Institute for Functional Medicine; 2008.

* Epigenetics—the study of how environmental factors can affect gene expression without altering the actual DNA sequence and how these changes can be inherited through generations.

* This section was excerpted and adapted from Galland L. Patient-centered care: antecedents triggers, and mediators. In Textbook of Functional Medicine, Ch. 8.

* Heuristics are rules of thumb—ways of thinking or acting—that develop through experimentation and enable more efficient and effective processing of data.

* Research focused on the therapeutic encounter has repeatedly found that clinicians interrupt the patient’s flow of conversation within the first 18 seconds or less, often denying the patient an opportunity to finish. (Beckman DB, et al. The effect of physician behavior on the collection of data. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:692-696.)