Chapter 27 Full-Endoscopic Interlaminar Lumbar Discectomy and Spinal Decompression

Minimally invasive techniques can reduce damage to tissues and limit the consequences of necessary tissue damage [1,2]. Endoscopic operations possess advantages that raise these procedures to the standard in many areas. Working with lens optics under lavage provides excellent visual conditions, and bleeding can be reduced. Also, the use of the laser or high-frequency bipolar current is possible in the immediate vicinity of neural structures [3]. The prerequisite for any minimally invasive technique is that the technical possibilities of such operations guarantee attainment of the operative goal [4].

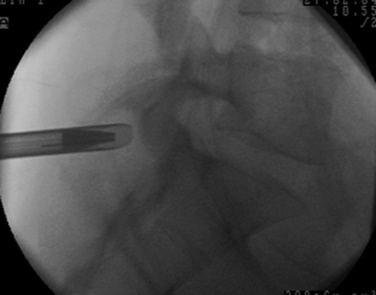

The most common fully endoscopic uniportal procedure is the transforaminal or extraforaminal operation with posterolateral access (Fig. 27-1) [5–8]. It is seldom technically possible to perform retrograde resection of disorders within the spinal canal intradiscally. For this reason, the newly developed lateral access is necessary within the transforaminal technique to reach such structures because of the bony boundaries of the intervertebral foramen and the access pathway through the soft tissue (Fig. 27-2) [9]. At the caudal levels, this access may be hindered by the pelvis. Additionally, the boundaries of the foramen hamper mobility during the procedure and limit the available room to work in the spinal canal.

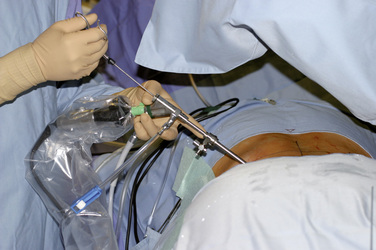

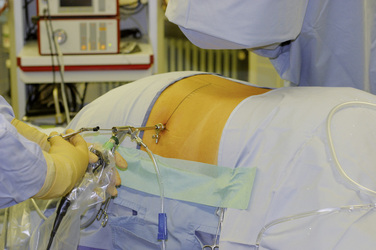

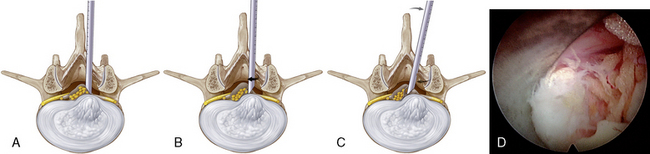

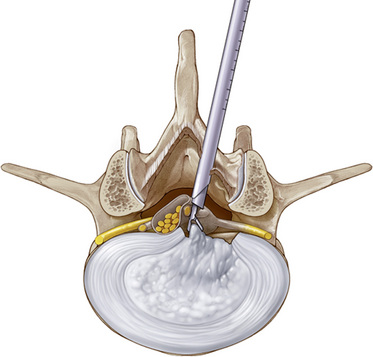

The fully endoscopic uniportal interlaminar technique can be used for transforaminal lumbar problems that are technically inoperable. The spinal canal is reached through the interlaminar window and enables working comparable to that with conventional techniques but in a minimally invasive procedure (Fig. 27-3) [1,10,11]. The known problems of open, microscopic, and endoscopically assisted techniques can be reduced [1,2].

At the same time, technical problems have been solved by the development of new lens endoscopes with intra-endoscopic 4.2-mm working canals and corresponding new instruments, shavers, and burs (Fig. 27-4). This development also enables the resection of bones as in arthroscopic surgery [10,11].

Advantages

Conventional open operating procedures are indispensable today and will remain so in the future. The possible complications of and injuries from such procedures are known [12–19]. At the least, new techniques must be as capable of attaining the operative goals as the established procedures [4].

Minimized bony and ligamentous resection, according to current knowledge, resulting in reduction of operation-induced instabilities

Minimized bony and ligamentous resection, according to current knowledge, resulting in reduction of operation-induced instabilitiesIndications

The indications for the operation correspond to today’s valid standards [20]. Most experience has been gained in the therapy of disc herniations and lateral spinal canal stenosis. Extensive central spinal canal stenosis has been operated on for only a short time, and the procedure is still under development. Existing concurrent pathologies, such as instabilities, must be treated at the same time as appropriate. The following indications are currently clearly defined:

Sequestered or nonsequestered disc herniations within the spinal canal: In the case of extensive dislocation to the next level, a two-level procedure may be performed; in the case of a herniation in combination with intraforaminal-extraforaminal prolapses, an additional fully endoscopic transforaminal operation may be performed.

Sequestered or nonsequestered disc herniations within the spinal canal: In the case of extensive dislocation to the next level, a two-level procedure may be performed; in the case of a herniation in combination with intraforaminal-extraforaminal prolapses, an additional fully endoscopic transforaminal operation may be performed.Contraindications

Compressing intraforminal or extraforaminal pathologies: In this case a fully endoscopic transforaminal or extraforaminal procedure with posterolateral to lateral access is indicated.

Compressing intraforminal or extraforaminal pathologies: In this case a fully endoscopic transforaminal or extraforaminal procedure with posterolateral to lateral access is indicated.Preoperative preparation

Examination

The decision for surgery must be made according to today’s standard on the basis of radicular pain symptoms and existing neurologic deficits [20]. Isolated back pains cannot usually be improved by decompressing operations.

The decision for surgery must be made according to today’s standard on the basis of radicular pain symptoms and existing neurologic deficits [20]. Isolated back pains cannot usually be improved by decompressing operations.Informed Consent

Patients must be informed about their disease and its possible long-term course and consequences. Despite the minimal invasiveness and attendant advantages of the surgical procedure, all known side effects, complications, and therapeutic possibilities must be explained, as would be done for conventional procedures [21].

Patients must be informed about their disease and its possible long-term course and consequences. Despite the minimal invasiveness and attendant advantages of the surgical procedure, all known side effects, complications, and therapeutic possibilities must be explained, as would be done for conventional procedures [21]. With reference to the fully endoscopic procedure, it must be pointed out that even with minimally invasive interventions, scarring cannot be completely avoided, and the extent of scarring will depend on the possible need to expand the surgical procedure.

With reference to the fully endoscopic procedure, it must be pointed out that even with minimally invasive interventions, scarring cannot be completely avoided, and the extent of scarring will depend on the possible need to expand the surgical procedure.Procedure

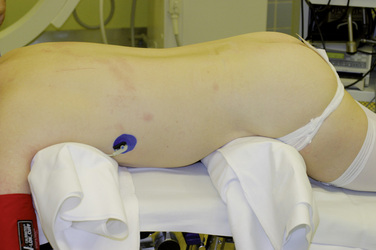

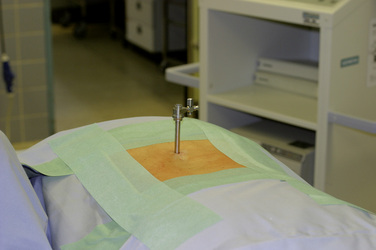

The fully endoscopic interlaminar operation is usually performed with the use of general anesthesia.

Figure 27–8 The stab incision may be extended to the muscle fascia if needed to facilitate insertion of the dilator.

Figure 27–9 The dilator is inserted to the ligamentum flavum or the bony boundary of the zygapophyseal joint.

Figure 27–12 The operating sheath with beveled opening is inserted through the dilator toward the ligamentum flavum.

Figure 27–14 The operating sheath is in its final position, with the opening turned medially, opposite the sheath grip.

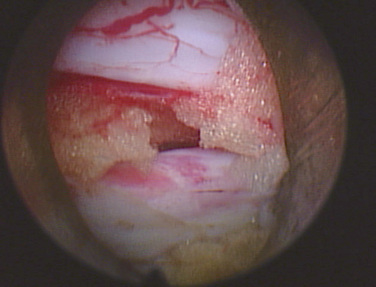

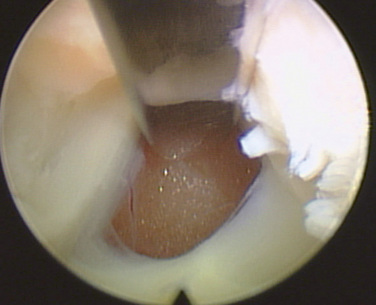

Figure 27–16 The ligamentum flavum is incised as laterally as possible to keep the medial defect as small as possible.

The further operative steps depend on the pathology, as follows:

Disc herniations, cysts of the zygapophyseal joint, and lateral spinal canal expansions can usually be corrected without further access-related resections.

Disc herniations, cysts of the zygapophyseal joint, and lateral spinal canal expansions can usually be corrected without further access-related resections. In extended sequestered dislocations, the resection of segments of the lamina either cranial or caudal to the current segment may be necessary before the ligamentum flavum is opened, in accordance with preoperative planning (Fig. 27-18).

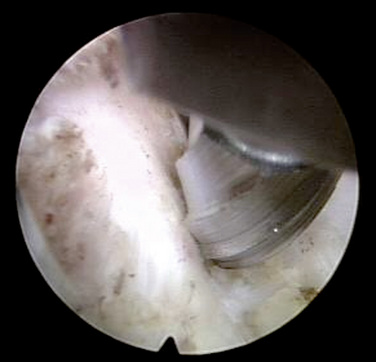

In extended sequestered dislocations, the resection of segments of the lamina either cranial or caudal to the current segment may be necessary before the ligamentum flavum is opened, in accordance with preoperative planning (Fig. 27-18). The operating sheath with beveled opening can be used as a second instrument and as a nerve hook. Turning the opening allows the neural structures to be held aside and protected (Fig. 27-19).

The operating sheath with beveled opening can be used as a second instrument and as a nerve hook. Turning the opening allows the neural structures to be held aside and protected (Fig. 27-19). Mobility within the spinal canal is controlled with the use of the optics, on the joystick principle (Fig. 27-20).

Mobility within the spinal canal is controlled with the use of the optics, on the joystick principle (Fig. 27-20). Various rigid and flexible instruments of different sizes, as well as shavers and burs, are available for each working step (Fig. 27-21).

Various rigid and flexible instruments of different sizes, as well as shavers and burs, are available for each working step (Fig. 27-21). Radiofrequency bipolar current is used for preparation and hemostasis. Use of holmium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Ho:YAG) laser ablation is not necessary.

Radiofrequency bipolar current is used for preparation and hemostasis. Use of holmium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Ho:YAG) laser ablation is not necessary. At the end of the operation, the instruments are removed and the incision closed. No drainage is required.

At the end of the operation, the instruments are removed and the incision closed. No drainage is required.

Figure 27–20 Control of the entire optic system on the joystick principle provides the required mobility.

Complications

Possible complications during microsurgical procedures are known and have been described in numerous publications [2,21–23]. A minimally invasive procedure reduces the rate of complications [1,2], but statistically, they cannot be completely prevented. Basically, all of the complications known for conventional procedures can occur.

Conclusion

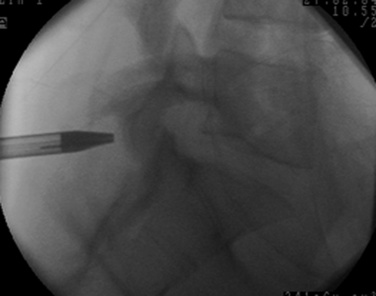

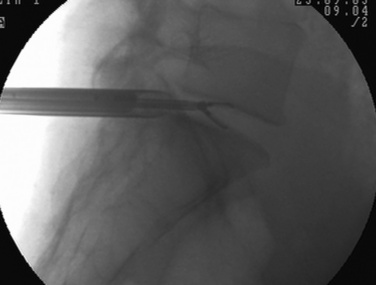

Consistent reduction of leg pain, as one of the main therapeutic criteria, can be regarded as an indication of sufficient decompression under fluoroscopic guidance. The success rate for microscopically assisted operations is between 75% and 100% [9,24,25]. Operation times, tissue traumatization, and complications are minimized [2,22,23]. Corresponding to the published advantages of a minimally invasive intervertebral and epidural procedure [26–28], there is no progression of existing symptoms. According to today’s understanding, the possibility of reducing or eliminating ossary and ligamentary resection as well as the minimally traumatic extirpation of the intervertebral space serves to avoid operation-induced instabilities [27–31]. Operation-related rehabilitative measures are not necessary. There is a comparably high rate of return to patients’ professional and athletic activity levels [8], with no greater morbidity of concurrent problems [22,23].

The recurrence rate is comparable to that of conventional techniques [32,33]. Revisions can be performed with the same technique. The negative effects of total resection of a degenerated nucleus, of which the biomechanical value is questionable, have not yet been completely elucidated [28,34]. Minimization of the anular defect may have greater protective influence than nucleus preservation [34].

Epidural scarring, which must be expected in conventional techniques and may lead to clinical symptoms in up to 10% or more of cases, is less with this technique [14,18,19]. Repeated endoscopic or conventional interventions can be performed without difficulty, and no lengthening of operation time has been reported [35]. In addition, the epidural lubricating tissue is preserved. This preservation corresponds to descriptions of better results with reduced traumatization of the ligamentum flavum [36].

Total and safe resection of herniated discs and other pathologies within the spinal canal must be performed under fluoroscopic guidance. Within the fully endoscopic uniportal procedure, the transforaminal operation is rated less traumatizing than the interlaminar operation because of the less extensive bony and ligamentous resections required. At the same time, the transforaminal procedure does have clear technical limitations. Thus, interlaminar access is indicated for problems that are technically inoperable with a transforaminal procedure, with the appropriate criteria taken into account. Overall the surgical approach is determined by the anatomy and pathology. Newly developed endoscopes with a 4.2-mm work canal and corresponding instruments enable resections of hard tissue [10,11].

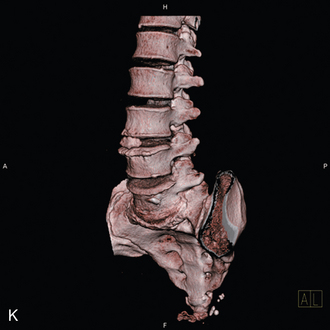

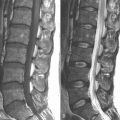

In summary, the available study results show the possibility of sufficient decompression equal to that of conventional procedures, which must be achieved as the minimum measure of a new procedure [4]. At the same time, the procedure has the advantages of a truly minimally invasive procedure. The technique described here offers a sufficient and safe alternative to open or microscope- or endoscope-assisted procedures (Figs. 27-22 and 27-24) that can be used to remove a herniated disc of any size. With the possibility of selecting an interlaminar or transforaminal, posterolateral to lateral procedure, pathologies outside and inside the lumbar spinal canal can be

Figure 27-24 There is a lavage fluid collection in the L5-S1 space 2 hours after full-endoscopic interlaminar discectomy.

sufficiently operated with the fully endoscopic uniportal technique, with the appropriate criteria taken into account.

1 Schick U., Dohnert J., Richter A., et al. Microendoscopic lumbar discectomy versus open surgery: An intraoperative EMG study. Eur Spine J. 2002;11:20-26.

2 Weber B.R., Grob D., Dvorak J., et al. Posterior surgical approach to the lumbar spine and its effect on the multifidus muscle. Spine. 1997;22:1765-1772.

3 Ruetten S., Meyer O., Godolias G. Application of holmium:YAG laser in epiduroscopy: Extended practicabilities in the treatment of chronic back pain syndrome. J Clin Laser Med Surg. 2002;20:203-206.

4 Maroon J.C. Current concepts in minimally invasive discectomy. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:137-145.

5 Kambin P., O’Brien E., Zhou L., et al. Arthroscopic microdiscectomy and selective fragmentectomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;347:150-167.

6 Lew S.M., Mehalic T.F., Fagone K.L. Transforaminal percutaneous endoscopic discectomy in the treatment of far-lateral and foraminal lumbar disc herniations. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:216-220.

7 Mathews H.H. Transforaminal endoscopic microdiscectomy. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1996;7:59-63.

8 Yeung A.T., Tsou P.M. Posterolateral endoscopic excision for lumbar disc herniation: Surgical technique, outcome and complications in 307 consecutive cases. Spine. 2002;27:722-731.

9 Ruetten S., Komp M., Godolias G. An extreme lateral access for the surgery of lumbar disc herniations inside the spinal canal using the full-endoscopic uniportal transforaminal approach: Technique and prospective results of 463 patients. Spine. 2005;30:2570-2578.

10 Ruetten S., Komp M., Godolias G. Full-endoscopic interlaminar operation of lumbar disc herniations using new endoscopes and instruments. Orthop Praxis. 2005;10:527-532.

11 Ruetten S. The full-endoscopic interlaminar approach for lumbar disc herniations. In: Mayer H.M., editor. Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery: A Surgical Manual. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2005:346-355.

12 Abumi K., Panjabi M.M., Kramer K.M., et al. Biomechanical evaluation of lumbar spinal stability after graded facetectomies. Spine. 1990;15:1142-1147.

13 Cooper R., Mitchell W., Illimgworth K., et al. The role of epidural fibrosis and defective fibrinolysis in the persistence of postlaminectomy back pain. Spine. 1991;16:1044-1048.

14 Fritsch E.W., Heisel J., Rupp S. The failed back surgery syndrome: Reasons, intraoperative findings and long term results: A report of 182 operative treatments. Spine. 1996;21:626-633.

15 Kaigle A.M., Holm S.H., Hansson T.H. Experimental instability in the lumbar spine. Spine. 1995;20:421-430.

16 Kato Y., Panjabi M.M., Nibu K. Biomechanical study of lumbar spinal stability after osteoplastic laminectomy. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:146-150.

17 Ruetten S., Komp M., Godolias G. Spinal cord stimulation using an 8-pole electrode and double-electrode system as minimally invasive therapy of the post-discotomy and post-fusion syndrome. Z Orthop. 2002;140:626-631.

18 Ruetten S., Meyer O., Godolias G. Epiduroscopic diagnosis and treatment of epidural adhesions in chronic back pain syndrome of patients with previous surgical treatment: First results of 31 interventions. Z Orthop. 2002;140:171-175.

19 Ruetten S., Meyer O., Godolias G. Endoscopic surgery of the lumbar epidural space (epiduroscopy): Results of therapeutic intervention in 93 patients. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2003;46:1-4.

20 Andersson G.B.J., Brown M.D., Dvorak J., et al. Consensus summary on the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 1996;21:75-78.

21 Mayer H.M. The microsurgical interlaminar, paramedian approach. In: Mayer H.M., editor. Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery: A Surgical Manual. New York: Springer Verlag; 2000:79-91.

22 Caspar W., Campbell B., Barbier D.D., et al. The Caspar microsurgical discectomy and comparison with a conventional standard lumbar disc procedure. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:78-87.

23 Stolke D., Sollmann W.P., Seifert V. Intra- and postoperative complications in lumbar disc surgery. Spine. 1989;14:56-59.

24 Andrews D.W., Lavyne M.H. Retrospective analysis of microsurgical and standard lumbar discectomy. Spine. 1990;15:329-335.

25 Hermantin F.U., Peters T., Quartararo L.A. A prospective, randomized study comparing the results of open discectomy with those of video-assisted arthroscopic microdiscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:958-965.

26 Balderston R.A., Gilyard G.G., Jones A.M., et al. The treatment of lumbar disc herniation: Simple fragment excision versus disc space curettage. J Spinal Disord. 1991;4:22-25.

27 Faulhauer K., Manicke C. Fragment excision versus conventional disc removal in the microsurgical treatment of herniated lumbar disc. Acta Neurochir. 1995;133:107-111.

28 Mochida J., Nishimura K., Nomura T., et al. The importance of preserving disc structure in surgical approaches to lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 1996;21:1556-1564.

29 Johnsson K.E., Redlund-Johnell I., Uden A., et al. Preoperative and postoperative instability in lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine. 1989;14:591-593.

30 Kambin P., Cohen L., Brooks M.L., et al. Development of degenerative spondylosis of the lumbar spine after partial discectomy: Comparison of laminotomy, discectomy and posterolateral discectomy. Spine. 1994;20:599-607.

31 Natarajan R.N., Andersson G.B., Padwardhan A.G., et al. Study on effect of graded facetectomy on change in lumbar motion segment torsional flexibility using three-dimensional continuum contact representation for facet joints. J Biomech Eng. 1999;121:215-221.

32 Hirabayashi S., Kumano K., Ogawa Y., et al. Microdiscectomy and second operation for lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 1993;18:2206-2211.

33 Wenger M., Mariani L., Kalbarczyk A., et al. Long-term outcome of 104 patients after lumbar sequestrectomy according to Williams. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:329-334.

34 Zollner J., Rosendahl T., Herbsthofer B., et al. The effect of various nucleotomy techniques on biomechanical properties of the intervertebral disc. Z Orthop. 1999;137:206-210.

35 Suk K.S., Lee H.M., Moon S.H., et al. Recurrent lumbar disc herniation: Results of operative management. Spine. 2001;26:672-676.

36 Aydin Y., Ziyal I.M., Dumam H., et al. Clinical and radiological results of lumbar microdiscectomy technique with preserving of ligamentum flavum comparing to the standard microdiscectomy technique. Surg Neurol. 2002;57:5-13.