14 Frontalis and HFL

Summary and Key Features

• Botulinum toxin can be safely utilized to treat horizontal forehead lines

• Most adverse effects resulting from the cosmetic use of botulinum toxin resolve spontaneously

• The risk of adverse outcomes after forehead treatment is increased by certain predisposing factors: age greater than 50 years, mild brow ptosis at baseline, pre-existing low eyelid platforms, and dermatochalasis

• Individualized injection techniques are recommended for individuals with tall (wide) and short (narrow) foreheads

• The frontalis muscle is very responsive to treatment and therefore low doses of toxin should be utilized initially

• Botulinum toxin (given around the time of suturing) has also been shown to be effective for minimizing the appearance of scars due to surgical and traumatic wounds

Side effects

Potential side effects from botulinum toxin use in the forehead include injection site pain, swelling, and bruising, as well as headache, eyebrow ptosis, eyelid ptosis, diplopia, and the development of new rhytides. New rhytides may appear as a result of overcompensation of untreated adjacent muscles. A case series by Kang et al (2011) of four patients receiving BoNT-A for HFLs reported the development of lower frontalis and glabellar protrusions as well as new unilateral forehead rhytides above the eyebrow. In all patients, most of the new rhytides were almost completely resolved within 4 weeks without further treatment. Indeed, the majority of side effects resulting from cosmetic use of botulinum toxin in the forehead as well as in other aesthetic regions resolve spontaneously without treatment.

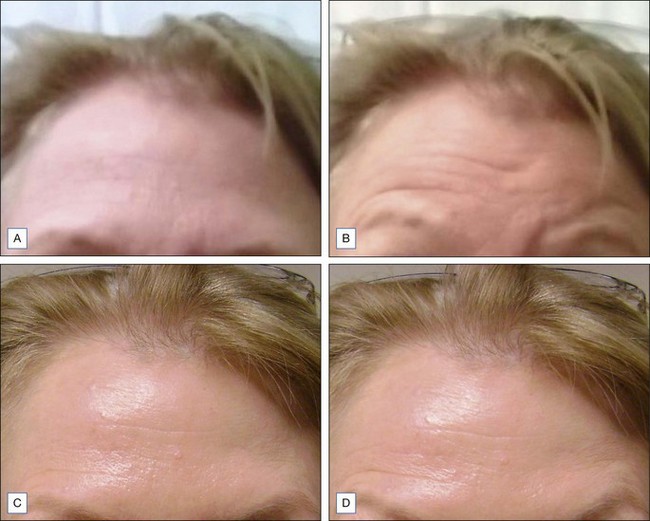

Other possible side effects from botulinum toxin treatment of HFLs include eyebrow and eyelid ptosis and periorbital edema, which are also self-limited. BoNT-A agents have been shown to spread up to 3 cm from the site of injection, but this may depend on the actual agent used and the method of dilution. Certain predisposing factors for eyebrow ptosis include age greater than 50 years and patients with mild eyebrow ptosis at baseline. Patients with pre-existing low eyelid platforms (i.e. the upper eyelid itself hangs down to or near the level of eyelashes) and dermatochalasis (Fig. 14.1; redundant skin at the eyebrow that hangs down toward the eyelid) should also be carefully evaluated to decide whether or not to proceed with treatment of the HFLs. Techniques that may help to prevent eyebrow ptosis include simultaneous treatment of brow depressors (especially the superior–lateral aspect of the orbicularis oculi) and to avoid eyelid ptosis by choosing injection points sufficiently superior to the orbital rim.

Injection techniques

Similar results for these two products have also been reported with the use of other dose ratios, for example by Nestor & Ablon (2011). A randomized, double-blinded, split-face study of 20 patients compared abobotulinumtoxinA and onabotulinumtoxinA at a 2.5 : 1 dose ratio, for the treatment of horizontal forehead lines. AbobotulinumtoxinA was shown to have a significantly longer duration of effect when compared with onabotulinumtoxinA. The median duration of full efficacy for abobotulinumtoxinA was 103 days and for onabotulinumtoxinA it was 87 days. Indeed, the optimal conversion ratio for complete bioequivalence has not yet been elucidated and it may be possible that 2.5 : 1 is too high as well, and that these products should be considered as completely independent products.

Treatment of scars

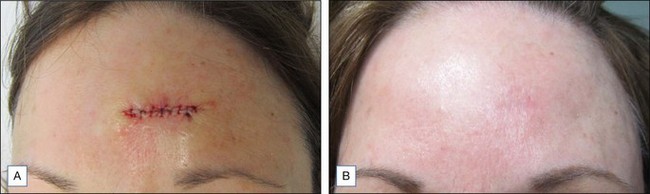

In addition to the management of rhytides, botulinum toxin has been an effective adjuvant treatment for minimizing scars (Fig. 14.4). This beneficial effect on scars is believed to be related to a decreased amount of tension and movement around an incision or wound site from toxin-mediated immobilization. The decrease in tension is believed to shorten the duration of the inflammatory phase of wound healing. Areas subject to greater tension and movement such as the chest, shoulders, and scapula are prone to hypertrophic scarring and keloid formation. A randomized-controlled trial reported by Gassner et al in 2000 involved six primates treated with BoNT-A versus placebo after undergoing symmetric pairs of standard excisions on either side of the forehead. The sides treated with BoNT-A were found to heal with a significantly better appearance than placebo-treated sides. The authors also noted that immobilization allows the surgeon to use finer sutures for closure, further contributing to a superior cosmetic outcome.

A study by Kadunc et al (2007) on the use of botulinum toxin A prior to resurfacing of the upper lip for upper perioral vertical rhytides demonstrated better results on the BoNT-A pretreated side. The authors suggested that this improvement may be not only related to less mechanical movement and stress across the healing wound, but also possibly to a decrease in metabolic activity in the area. Therefore, the effect of BoNT-A in helping to decrease scarring in sutured closures may be related to both phenomena.

More recently, a retrospective study by Flynn (2009) described the findings of patients receiving intraoperative botulinum toxin type A or B following reconstructive surgery after Mohs micrographic surgery for non-melanoma skin cancers and one case of melanoma in situ. Of the eighteen patients, the most commonly treated area was the forehead and the remaining areas included the nose, chin, glabella, scalp, and zygoma. Botulinum toxin was placed in a 1–2 cm radius around the suture lines. All patients exhibited good to excellent results with good apposition of wound edges. Again, a limitation of the study was the lack of a control group undergoing Mohs micrographic surgery and reconstruction without botulinum toxin injection. The authors noted that botulinum toxin type B (BoNT-B) has been reported to be faster-acting and of shorter duration – therefore type B may be better suited for use following surgical reconstruction. However, in this study, no differences were seen between sites treated with botulinum toxin type A and those treated with type B.

With reference to onset and spread between sub-types A and B of botulinum toxin, a small prospective split-face study involving eight patients, reported in 2003 by Flynn & Clark, examined the rate of onset and area of diffusion of botulinum toxin types A and B for moderate to severe forehead rhytides. Utilizing computer analysis and time-lapse motion pictures, botulinum toxin type B was found to have a slightly faster onset and larger radius of diffusion than BoNT-A. However, whether this difference is significant enough to produce a clinically visible difference in surgical scar healing remains to be seen.

Ascher B, Talarico S, Cassuto D, et al. International consensus recommendations on the aesthetic usage of botulinum toxin type A (Speywood Unit) – Part I: upper facial wrinkles. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2010;24(11):1278–1284.

Borodic GE, Ferrante R, Pearce LB, et al. Histologic assessment of dose-related diffusion and muscle fiber response after therapeutic botulinum A toxin injections. Movement Disorders. 1994;9(1):31–39.

Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Cohen J. A prospective, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, dose-ranging study of botulinum toxin type a in female subjects with horizontal forehead rhytides. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;29(5):461–467.

Carruthers A, Cohen JL, Cox SE, et al. Facial aesthetics: achieving the natural, relaxed look. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2007;9(suppl 1):6–10.

Carruthers J, Fagien S, Matarasso SL. Botox Consensus Group. Consensus recommendations on the use of botulinum toxin type a in facial aesthetics. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;114(6 suppl):1S–22S.

Carruthers JD, Glogau RG, Blitzer A. Facial Aesthetics Consensus Group Faculty. Advances in facial rejuvenation: botulinum toxin type a, hyaluronic acid dermal fillers, and combination therapies – consensus recommendations. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;121(5 suppl):S5–S30. quiz S31–S36

Dubois V, Vickers S. Bilateral inferior oblique palsies following botulinum toxin injections to the frontalis muscle. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery. 2006;59(10):1122.

Flynn TC, Clark RE, 2nd. Botulinum toxin type B (MYOBLOC) versus botulinum toxin type A (BOTOX) frontalis study: rate of onset and radius of diffusion. Dermatologic Surgery. 2003;5:519–522. discussion 522

Flynn TC. Use of intraoperative botulinum toxin in facial reconstruction. Dermatologic Surgery. 2009;35(2):182–188.

Garcia A, Fulton JE, Jr. Cosmetic denervation of the muscles of facial expression with botulinum toxin. A dose-response study. Dermatologic Surgery. 1996;22(1):39–43.

Gassner HG, Brissett AE, Otley CC, et al. Botulinum toxin to improve facial wound healing: A prospective, blinded, placebo-controlled study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2006;81(8):1023–1028.

Gassner HG, Sherris DA, Otley CC. Treatment of facial wounds with botulinum toxin A improves cosmetic outcome in primates. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2000;105(6):1948–1953. discussion 1954–1955

Kadunc BV, Trindade DE, Almeida AR, et al. Botulinum toxin A adjunctive use in manual chemabrasion: controlled long-term study for treatment of upper perioral vertical wrinkles. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33(9):1066–1072. discussion 1072

Kang SM, Feneran A, Kim JK, et al. Exaggeration of wrinkles after botulinum toxin injection for forehead horizontal lines. Annals of Dermatology. 2011;23(2):217–221.

Karsai S, Adrian R, Hammes S, et al. A randomized double-blind study of the effect of Botox and Dysport / Reloxin on forehead wrinkles and electromyographic activity. Archives of Dermatology. 2007;143(11):1447–1449.

Levy JL, Pons F, Jouve E. Management of the ageing eyebrow and forehead: an objective dose-response study with botulinum toxin. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2006;20(6):711–716.

Nestor MS, Ablon GR. Duration of action of abobotulinumtoxinA and onabotulinumtoxinA: a randomized, double-blind study using a contralateral frontalis model. Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. 2011;4(9):43–49.

Ozsoy Z, Genc B, Gözü A. A new technique applying botulinum toxin in narrow and wide foreheads. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2005;29(5):368–372.

Ozsoy Z, Genc B, Gözü A. A new technique for the application of botulinum toxin in short and tall foreheads. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2005;115(5):1439–1441.

Wilson AM. Use of botulinum toxin type A to prevent widening of facial scars. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;117(6):1758–1766. discussion 1767–1768