Chapter 18 Fractures of the Distal Humerus

Distal Humeral Hemiarthroplasty

Introduction

Distal humeral hemiarthroplasty (DHH), although first described in 1947, has only recently emerged as a surgical option for a number of distal humeral disorders. This has resulted from an improved understanding of the anatomy and biomechanics of the elbow,26 an increasing availability of anatomical prostheses and the recognition that DHH may provide advantages over current treatments for complex fractures of the distal humerus or pathology that destroys large segments of the distal humeral articular joint surface.

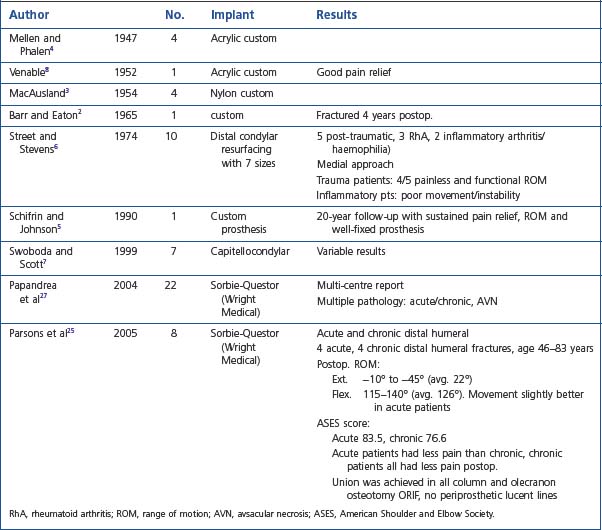

Early series reported the use of a small number of implants2–8 in a variety of pathologies, including trauma, inflammatory arthritis and tumour management. Prostheses were either custom made, non-anatomical (capitellocondylar, Kudo) or had anatomical components (Street). All these arthroplasties provided options other than open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), interposition arthroplasty and total elbow arthroplasty (TEA)9–11 for the treatment of complex elbow pathology.

Indications

The indications for DHH are currently evolving in terms of what is appropriate and achievable, and will continue to evolve as longitudinal studies provide more clinical data. My initial experience with DHH involved younger patients with comminuted fractures of the distal humeral joint surface, sometimes combined with a column fracture, where adequate ORIF was not achievable and the attendant outcomes were unsatisfactory. In addition, with the increased use of TEA for the treatment of comminuted distal humeral fractures in the elderly patient,12–1427 it was apparent that some older patients placed too high a demand on these TEAs and DHH provided a number of advantages.

Current indications for DHH include:

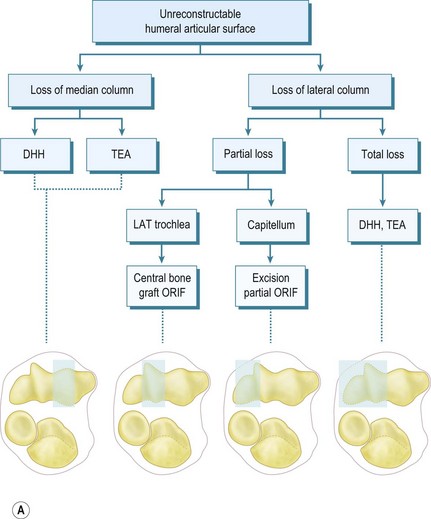

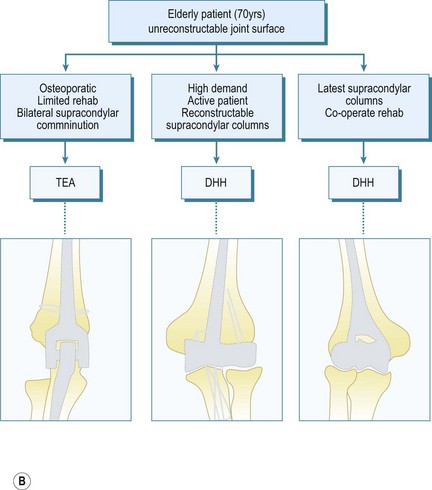

In terms of selecting whether ORIF, bone grafting, DHH, TEA or even radiocapitellar arthroplasty (RCA) is appropriate, this depends on the load-bearing columns involved, the age of the patient and the activity levels as outlined in the treatment algorithm (Fig. 18.1).

Figure 1A courtesy William PLT. Pocket picture guides to the anatomy of the joints: elbow joints. Gower Medical Publishing.

Summary Box 18.1 Indications and contraindications for DHH

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

| Acute trauma | Infection |

| Salvage of failed ORIF | Poor neurovascular status |

| Chronic malunion/non-union | Insufficient bone columns |

| Avascular necrosis of the trochlea | Loss of collateral ligaments and epicondyles |

| Tumours of the trochlea | Loss of radial head/coronoid |

Implants

Street and Stevens6 designed a near-anatomical DHH spool in 1974. However, experience with TEA and the mechanism of humeral component loosening suggests that DHH implants should be stemmed and preferably have an anterior flange to resist joint reactive forces. There are currently two TEA systems (Fig. 18.2) available that allow a DHH (Sorbie-Questor elbow, Wright Medical Technologies; and the Latitude elbow system, Tornier) and another under development (Coonrad/Morrey DHH, Zimmer). These current prostheses have their strengths and weaknesses. Advances in the understanding of elbow anatomy and biomechanics15–18 have helped determine the correct shape and sizing of joint surfaces, along with the landmarks for appropriate implantation ensuring good stability and function.

The Sorbie-Questor19 humeral component is a monobloc component with three sizes, which allows a best fit in 95% of all elbows. Its cupped condylar shape allows for impaction up into the supracondylar columns and humeral shaft, leaving adequate space for periarticular plates for column fixation. The stem, however, is relatively short and has no anterior flange to resist anteroposterior (AP) forces; thus condylar fixation is imperative to prevent implant loosening.

The Latitude system20 has three stem sizes (with an anterior flange) and six modular anatomical spools. Although reconstruction of the epicondyles is the preferred option, a central axis hole allows suture fixation of collateral ligament repair if required. Although both systems would theoretically allow conversion to a TEA, the practicality of this is still to be demonstrated. The use of an anterior flange in humeral implant design has been shown to give better long-term humeral stem fixation and may therefore result in improved outcome for the Latitude system. At present, however, it is too early to know if this will be borne out by the long-term results.

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

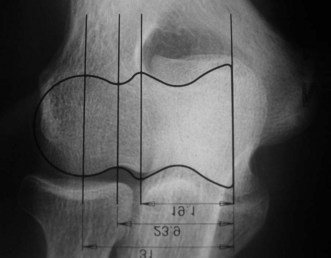

Preoperative imaging should include good AP and lateral radiographs of the elbow. In addition, since it is often unclear whether a fracture is reconstructable or will require a DHH, a CT scan should also be considered to help clarify the situation. If reconstruction is not achievable, an X-ray of the contralateral elbow will help with accurate templating (Fig. 18.3). Sizing is based on the direct correlation between the AP dimensions of the normal articular surface and the radii of the capitellum and trochlea. In addition, in the AP view, the longitudinal axis of the radial neck should align with the centre of the capitellum, while at the same time the prosthetic trochlea should align accurately with the trochlea or sigmoid fossa.

Surgical technique

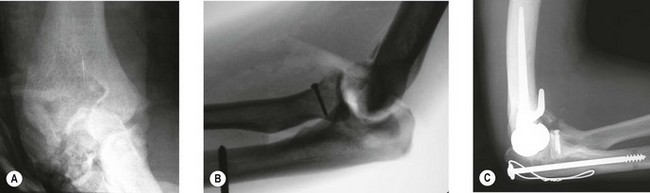

Timing of the procedure in relation to acute trauma does not appear to be crucial, as long as the procedure is undertaken within 7–10 days. As such it may be appropriate that the patient is transferred to a unit that has particular elbow or fracture expertise. On rare occasions soft tissue constraints mean an immediate DHH is not appropriate and stabilization with an external fixator with delayed DHH is an option (Fig. 18.4). Not infrequently it is only in theatre when the fracture is exposed that it is deemed to be unreconstructable. Thus in severely comminuted fractures both ORIF implants and DHH prostheses should be available when the patient is taken to the operating room.

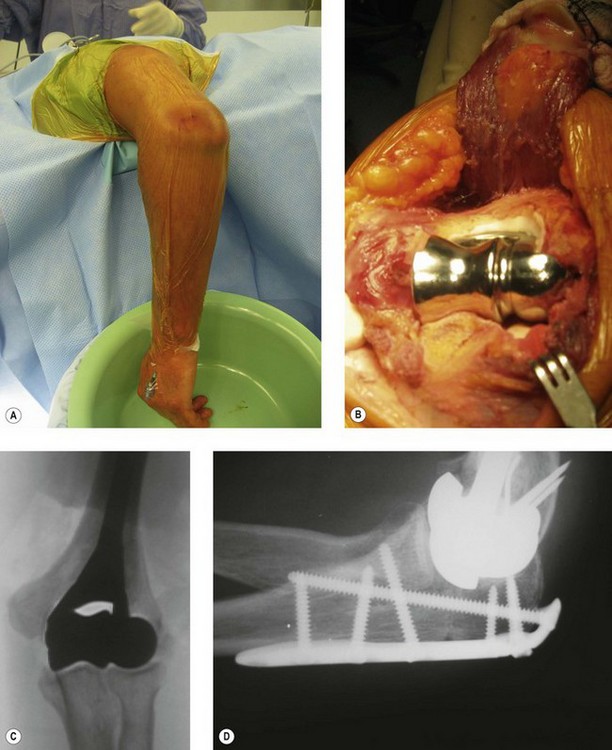

The patient is positioned in the lateral decubitus position (Fig. 18.5A) and the arm secured on an arm support. A high tourniquet is applied. This allows free use of the image intensifier intraoperatively and adequate clearance for the elbow to be flexed to 120° to facilitate insertion of the component. Following the chevron osteotomy of the ulna, the triceps is reflected and the articular segment wrapped in a saline-soaked gauze to protect the articular cartilage. The fracture is assessed, and if a DHH is to be undertaken the humerus is broached. If a supracondylar column ORIF is required then a trial component or broach is left in situ to maintain space for the prosthesis.

Frequently free-hand bone cuts are required to allow appropriate placement of the prosthesis. If the columns require reconstruction this must be undertaken anatomically with respect to the collateral ligament insertion and joint axis. Periarticular plate systems help with this step; however, with each additional column reconstruction the complexity of the procedure increases significantly. The depth and correct rotation of insertion of the implant are determined by aligning the axis of the component with the origins of the MCL ( anterior-inferior border of the medial epicondyle) and LCL (centre of the lateral epicondyle) humeral insertion points.21–24 The varus–valgus alignment is determined by placing the prosthetic stem centred in the humeral canal with the above alignments correct. Thus correct depth, rotation, valgus–varus and rotation orientation can be accurately restored (Fig. 18.5B, C).

Sizing of the component is determined by preoperative templating. It is checked intraoperatively by placing different-sized spools on the anterior sigmoid fossa and radial head and confirming that the centre of the radial head matches the centre of the capitellum, while maintaining good trochlear congruency. Lastly, full elbow flexion should be demonstrable to avoid ‘overstuffing’ of the joint (due to an oversized spool or a too distal placement of the component joint axis). Any tendency for rotatory instability or translocation of the joint is an indication that the prosthesis is misaligned relative to the ligament attachments (Table 18.2).

Cementing of the component should be performed with a cement restrictor and antibiotic-impregnated cement.25 Sometimes the anterior flange bone graft is too thick and can displace the axis of rotation too anteriorly. If this occurs, the bone graft should be reduced in size or placed once the stem is in situ and the cement has cured.

The olecranon osteotomy is fixed with either a strong tension band wire construct or an olecranon plate (Fig. 18.5D), which is buried beneath the soft tissues. The medial and lateral aspects of the osteotomy are always bone grafted with cancellous bone from the distal humeral fragments. The fixation and tracking of the arthroplasty are then assessed radiographically prior to closure in order to ensure joint stability and that no ORIF elements violate the articulation. In addition, a full range of motion should be present. Finally, the ulnar nerve must be inspected to confirm that it is not under undue tension.

Non-acute pathology

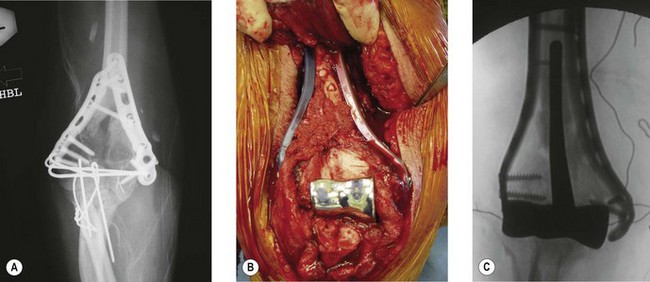

DHH can be used to salvage malunion (Fig. 18.6), non-union or tumour of the distal humerus, where osteotomy and fixation will not restore adequate articular columns. In non-union a thorough surgical debridement is performed, with tissue being sent for extended culture and histopathology. The principles of column reconstruction, restoration of joint axis and accurate placement of the component remain the same. A shortening osteotomy maybe required along with autologous bone graft. The possible compromise of stable component fixation in complex cases means that the utilization of a prosthesis with an anterior flange and bone grafting is an important step in achieving good long-term fixation.

Rehabilitation

Patients are started on a protocol of elevation, compression, ice and passive movement from 20° to 100°, utilizing a self-guided programme of flexion/extension stretches or a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine. Night-time extension static splinting is utilized if there is a tendency for the patient to develop a flexion contracture. At 4–6 weeks, when union of the osteotomy is progressing, active exercises are commenced (Fig. 18.7). Long-term restrictions are empirical, in that patients are advised to moderate heavy or repetitive loads on the elbow and to avoid impact tools/activities. There are no data yet to give a clear guide at this point in time.

Outcome and literature review

The longest follow-up of a custom hemiarthroplasty is 20 years with good pain relief and functional movement.5 The literature is limited and is summarized in Table 18.1. Street and Stevens4 reported their experience of 10 distal humeral anatomical spools (no stem). Five patients had inflammatory arthritis and reported poor movement and implant instability. Five patients were post-traumatic and four were pain free and had good functional movement. Swoboda and Scott7 published their experience of the capitocondylar humeral component (non-anatomical) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and noted variable results. Parsons et al,26 using the Sorbie-Questor prosthesis, reported their initial experience of DHH in trauma (four acute and four chronic). The average range of movement was 22–126°, with pain improved in all cases.

Complications

Many potential complications of implant instability, joint stiffness and loosening can be avoided with attention to detail and achieving an anatomical implantation. This requires a clear understanding of the collateral ligament anatomy and its relationship to the distal humerus (Table 18.2). Most reoperations are in relation to the removal of tension band wires; however, this is a small price to pay for getting the biomechanics of the arthroplasty ‘right’. Heterotopic ossification is occasionally seen and is eminently salvageable, with a standard surgical release 6 months after the DHH as per a normal post-traumatic stiff elbow. A small number of patients have developed a medial trochlear spur that appears to be due to the edge of the anatomical spool. Progression with time will need to be assessed.

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Flexion contracture (intraoperative) |

PLRI, posterolateral rotatory instability; EUA, examination under anaesthetic.

1 O’Driscoll SW, Jaloszynski R, Morrey BF, An KN. Origin of the medial ulnar collateral ligament. J Hand Surg. 1992;17:164-168.

2 Barr JS, Eaton RG. Elbow reconstruction with a new prosthesis to replace the distal end of the humerus: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965;47:1408-1413.

3 MacAusland WR. Replacement of the lower end of the humerus with a prosthesis: a report of four cases. Western J Surg Gynec Obstet. 1954;62:557-566.

4 Mellen RH, Phalen GS. Arthroplasty of the elbow by replacement of the distal portion of the humerus with an acrylic prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1947;29:348-353.

5 Shifrin PG, Johnson DP. Elbow hemiarthroplasty with 20-year follow-up study: a case report and literature review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:128-133.

6 Street DM, Stevens PS. A humeral replacement prosthesis for the elbow: results of ten elbows. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56A:1147-1158.

7 Swoboda B, Scott RD. Humeral hemiarthroplasty of the elbow joint in young patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a report on 7 arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:553-559.

8 Venable CS. An elbow and an elbow prosthesis. Am J Surg. 1952;83:271-275.

9 Frankle MA, Herscovici D, DiPasquale TG, et al. A comparison of open reduction and internal fixation and primary total elbow arthroplasty in the treatment of intra-articular distal humerus fractures in women older than age 66. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17(7):473-480.

10 Gambirasio R, Riand N, Stern R, et al. Total elbow replacement for complex fractures of the distal humerus: an option for the elderly patient. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:974-978.

11 Ray PS, Kakarlapudi K, Rajsekhar C, et al. Total elbow arthroplasty as primary treatment for distal humeral fractures in elderly patients. Injury. 2000;31:687-692.

12 Cobb TK, Morrey BF. Total elbow arthroplasty as primary treatment for distal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(6):826-832.

13 Garcia JA, Mykula R, Stanley D. Complex fractures of the distal humerus in the elderly: the role of total elbow replacement as primary treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:812-816.

14 Obremskey WT, Bhandari M, Dirschl DR, Shemitsch E. Internal fixation versus arthroplasty of comminuted fractures of the distal humerus. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:463-465.

15 Beckett KS, McConnell P, Lagopoulos M, et al. Variations in the normal anatomy of the collateral ligaments of the human elbow joint. J Anat. 2000;197(3):507-511.

16 Cohen MS, Bruno RJ. The collateral ligaments of the elbow: anatomy and clinical correlation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;February(383):123-130.

17 Malone AA, Zarkadas PC, Hughes J, et al. American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons open meeting on biologics in shoulder surgery. November 2006.

18 Wevers HW, Siu DW, Broekhoven LH, Sorbie C. Resurfacing elbow prosthesis: shape and sizing of the humeral component. J Biomed Eng. 1985;7:241-246.

19 Inagaki K, O’Driscoll SW, Neale PG, et al. Importance of the radial head component in Sorbie unlinked total elbow arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;400:123-131.

20 Gramstad GD, King GJ, O’Driscoll SW, et al. Elbow arthroplasty using a convertible implant. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2005;9:153-163.

21 Blewitt N, Pooley J. An anatomic study of the axis of the elbow movement in the coronal plane: relevance to component alignment in elbow arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1994;3:151-158.

22 Cohen MS, Hastings HN. Rotatory instability of the elbow: the anatomy and role of the lateral stabilizers. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:225-233.

23 Floris S, Olsen BS, Dalstra M, et al. The medial collateral ligament of the elbow joint: anatomy and kinematics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:345-351.

24 Ochi N, Ogura T, Hashizume H, et al. Anatomic relation between the medial collateral ligament of the elbow and the humero-ulnar joint axis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:6-10.

25 Faber KJ, Cordy ME, Milne AD, et al. Advanced cement technique improves fixation in elbow arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;January(334):150-156.

26 Parsons M, O’Brien R, Jason H, Hughes JS. Elbow hemiarthroplasty for acute and salvage reconstruction of intra-articular distal humerus fractures. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;6:87-97.

27 Papandrea R, Hughes J, Sorbie C, et al. Prosthetic hemiarthroplasty of the distal humerus. ASES Meeting, November 2004.