Foreign Bodies

Perspective

When people ingest or insert foreign bodies, a brief history may be sufficient to establish the diagnosis, guide initial management decisions, and predict the process required for definitive removal. Sometimes, however, diagnosis and management of a foreign body might require a meticulous history and insightful care. Those at higher risk of having a foreign body include neurologically impaired patients, edentulous individuals, patients with certain psychiatric diagnoses, incarcerated individuals, and individuals at the extremes of age. In these same groups, definitive history is often elusive, and the clinician should use situational clues. Even when patients are fully cooperative, the diagnosis of foreign body ingestion or insertion can be difficult, especially when the expression of the foreign body is delayed. Although foreign body cases are usually not diagnostic dilemmas, the emergency physician should keep in mind the unusual possibility of “foreign body mimics” (e.g., angioedema manifesting as esophageal foreign body sensation).1

Principles of Disease

When the foreign body represents an immediate threat to the patient, as is the case with an airway foreign body, the need for urgent extraction is obvious. Trauma-related foreign bodies, such as knives and bullets, pose important management decisions (see other trauma chapters in this text). Even in cases in which no immediate life threat exists, some foreign bodies should be removed because of the threat of injury from the nature or constituents of the foreign body. For instance, cocaine can kill a body packer,2 an impacted button battery can cause fatal electrochemical tissue damage,3 and an insect can damage otic structures.4

Eye

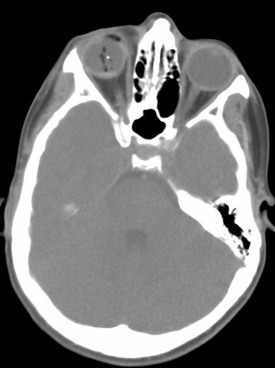

Although wooden and metallic fragments are found most frequently, ophthalmic foreign objects vary widely. The diagnosis usually is self-evident. However, extraocular and intraocular foreign bodies may be subtle in presentation, with mild symptoms and uncharacteristic histories involving seemingly trivial trauma, such as brushing against a bush or falling. In some cases, foreign bodies are identified in intoxicated patients with abnormal ocular examination findings and no known history of trauma (Fig. 60-1). Early diagnosis, appropriate care, and follow-up minimize the risks of delayed sequelae, such as endophthalmitis (which may occur within 48 hours after foreign body introduction) or sight-threatening siderosis bulbi.5,6 Controversy regarding foreign body removal and its timing does not diminish the importance of making the initial diagnosis.

History

Most patients report a foreign body sensation (often on blinking) and cannot see the foreign body. If the object is corneal, the patient may be able to see something in the visual field or may see the foreign body when looking in the mirror. The patient also may complain of frequent or constant lacrimation and conjunctival reddening. Foreign bodies that create corneal injury and are no longer present may account for symptoms identical to those noted in the presence of a foreign body. In addition, patients may have symptoms in the absence of any history of known foreign body. In these cases the occupational and social history, including pets and hobbies, may shed light on the diagnosis. Another important component of the history is whether radial keratotomy has been performed. This procedure is associated with potential for foreign body entrapment in the corneal incisions, which can gape as long as 6 or more years postprocedure.7

Physical Examination

The initial survey includes standard elements of the emergency department (ED) eye examination. Early visual acuity is an important predictor of final visual outcome in cases of intraocular foreign body.8 During slit-lamp examination, the emergency physician may detect a corneal foreign body by the shadow it casts on the iris. The slit lamp can facilitate identification of rust rings, and fluorescein can aid in detecting abraded corneal epithelium. The inner aspects of both lids must be examined. The lower lid is often successfully exposed with gentle manual retraction outward and downward as the patient looks upward. The upper lid is usually exposed through eversion by instructing the patient to look downward while upward traction on the eyelashes is applied; an applicator stick is placed, to act as a fulcrum, on the proximal edge of the tarsal plate. After location and removal of one foreign body, complete examination should seek presence of other ocular objects.

Diagnostic Strategies

The foreign body may have penetrated the anterior eye structures and entered the globe (see Fig. 60-1). If the history and mechanism of injury are compatible with ocular penetration by radiopaque material, or if a small wound of the globe is noted, anteroposterior and lateral radiography of the orbit is a reasonable initial step. However, the multiple advantages of computed tomography (CT) render this technique the preferred first choice when intraocular penetration is strongly suspected.9 As compared with plain radiographs, CT delivers less radiation to the lens. Multiplanar reconstruction minimizes streak artifacts, affording better localization of intraorbital objects. When globe penetration is strongly suspected, staining with fluorescein is best avoided owing to obscuration of the physical examination. When perforation is judged unlikely and fluorescein is administered, identification of rivulets of fluorescein tracking from the puncture (i.e., positive Seidel test result) is helpful in identifying the fact that intraocular penetration has occurred. In one case series of 288 patients, Luo and Gardiner reported a near-zero incidence of intraocular foreign body in patients with corneal metal foreign bodies after low-velocity (nonexplosive) exposures.10

Ultrasound is a useful adjunct to CT scanning in patients with foreign bodies that are difficult to localize.11 When CT will be delayed, or if ionizing radiation is a concern, two ultrasound techniques can be useful in searching for foreign bodies. B-scan ultrasound, available in many EDs, has occasionally been reported successful in detecting foreign bodies missed on ophthalmologic examination.6,12 For patients in whom a foreign body is suspected despite negative ED workup and imaging, the more advanced technique of ultrasound biomicroscopy, available in ophthalmologic specialty centers, is helpful. The sensitivity of this modality is sufficient that it detects foreign bodies not visible by direct or indirect ophthalmologic examination, traditional B-scan ultrasound, or CT.13 Given the lack of reported case series and justifiable concerns about eye damage from mobilization of ferromagnetic foreign objects, use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for ophthalmologic foreign body imaging remains controversial.5

Management

In nearly all cases, therapy is removal of the foreign body. If the object is located on the bulbar or palpebral conjunctiva (not the cornea), it often can be removed easily by sweeping the site with a moist cotton-tipped applicator. Usually, other instruments are required (Fig. 60-2). Occasionally, if the foreign body is large, it may be extracted with forceps. For small corneal foreign bodies, after application of topical ocular anesthesia, it is often necessary to use an eye spud or small-gauge needle to move gently underneath one end of the object and pick it out; magnification is usually helpful. If the attempts at foreign body removal are unsuccessful or if the foreign body is deeply embedded, preventing removal, the patient should be referred for object removal within 24 to 48 hours. Although there is a paucity of evidence addressing the oxidation rate of metallic corneal foreign bodies, prudence dictates early “rust ring” to minimize growth of metallic oxides. Overly vigorous attempts at removal may cause anterior chamber perforation. It is prudent for the emergency physician to avoid significant corneal procedures in patients who have had a laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) procedure for nearsightedness.

Ear

History

In patients with ear complaints with recent travel or camping history or poor living conditions, geographic information may suggest insects inhabiting the external ear canal; in most cases, the cockroach is the culprit.14

Patients with foreign bodies in the ear may have secondary symptoms related to pathology in adjacent structures. Malocclusion may be the chief complaint if the foreign body erodes to the temporomandibular joint.15 Similar erosion has caused otic foreign bodies to manifest as eustachian tube dysfunction, parapharyngeal abscess, or mastoiditis with progression to fatal brain abscess and meningitis.16 Such events are exceedingly rare.

Physical Examination

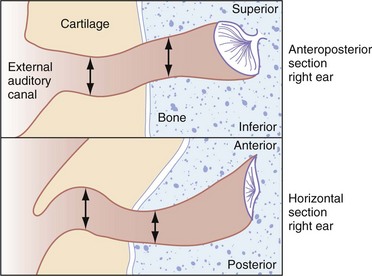

The external auditory canal is cylindrical with an elliptic cross section (Fig. 60-3). A thin layer of sensitive epithelium covers an outermost cartilaginous portion and an inner bony segment. There are two anatomic points of narrowing (and foreign object lodging) within the canal: (1) near the inner end of the cartilaginous portion of the canal and (2) at the point of bony narrowing called the isthmus.

Figure 60-3 Horizontal and vertical cross sections of external ear canal showing points of anatomic narrowing.

Inspection of the tympanic membrane is important because it may have been ruptured by the foreign object or by prior removal attempts. If so, medical documentation should indicate that this rupture was present before attempts at foreign object removal. As in other body locations (especially the nose), the risk of multiple foreign objects is such that if one foreign object is identified, the emergency physician should search for additional material.17

Management

In most cases, foreign body removal attempts may be instituted in the ED. Presence of a foreign body for more than a day or in a very young patient (younger than 4 years) does not constitute an independent risk factor for foreign body removal failure or complication; the emergency physician may thus proceed with removal efforts if not otherwise contraindicated.18 The patient should be informed about the extreme sensitivity of the auditory passage and the likely discomfort and potential for minor bleeding. Sedation may be important to minimize patient discomfort and reduce risks of iatrogenic trauma. Lidocaine instillation may aid in topical anesthesia; liquid 1% or 2% solution is preferred to gel preparations, which impair visualization needed for removal. Less often, foreign body removal requires local anesthesia of the external ear canal. The anesthesia instillation procedure, which may cause patient discomfort and iatrogenic injury, is performed by injecting all four quadrants of the canal with lidocaine via a tuberculin syringe inserted through an otic speculum. In cases of a refractory foreign body and an uncooperative patient, definitive management should be performed with procedural sedation or even general anesthesia. Although the evidence is not universally consistent, available data suggest that approximately 95% of aural foreign bodies can be removed without the need for general anesthesia.19

When the ear canal is inhabited by an insect, it is important to kill or immobilize the creature to facilitate its removal. Immobilization reduces the chance of patient discomfort or ear damage caused by an insect attempting to evade forceps introduced into the ear canal. Patient comfort may also be optimized by minimization of shining light into an ear canal inhabited by light-avoiding insects (such as cockroaches). Different immobilizing agents have different reported success rates. Efficacious formulations include lidocaine as a 10% spray or less concentrated liquid, 2% lidocaine gel, mineral oil with 2% or 4% lidocaine, and alcohol.4 One study suggests that microscope immersion oil is more efficacious than lidocaine preparations.20

Several extrication methods may prove effective, and various instruments may be useful (Fig. 60-4). Small objects often can be removed by the application of suction with a small plastic catheter. With soft or irregularly shaped objects, it is often possible to grasp the foreign body with forceps (alligator forceps may be best) and remove it either in one piece or in fragments. If the object cannot be grasped, it may be possible to remove it by passing a blunt-tipped right-angle hook beyond the foreign body and gently coaxing it out. Alternatively, a balloon-tipped catheter can be passed distal to the object, with subsequent attempts to withdraw the (inflated) balloon and extract the object. Any balloon-tipped catheter design may be used, as long as its caliber is small enough (about 18 gauge or smaller) to allow comfortable introduction into the ear canal; a typical commercial device is shown in Figure 60-5.

Indirect methods for foreign body removal also have been used with some success. The irrigation technique takes advantage of the elliptic shape of the external ear canal. A stream of room-temperature water or saline should be directed at the (nonvegetable) foreign body’s periphery via a 20-mL syringe and a 14- or 16-gauge catheter (this setup is safe in terms of pressure on the tympanic membrane).21 The hope with irrigation is that the jet of water will be directed past the object, against the tympanic membrane, and finally against the posterior aspect of the foreign body, driving it out of the canal. There are no significant complications with use of the technique, and it is well tolerated by children and adults. This modality should not be used if there is a known history or clinical suspicion of tympanic membrane perforation.

Removal of objects from the middle ear with cyanoacrylate adhesive-tipped swabs has been recommended in the past. This technique carries the risk, however, of contaminating the ear canal with a substance that is difficult to remove and has been associated with tympanic membrane rupture.22 Insufficient evidence exists to condone or condemn this technique.

If these methods are unsuccessful or if the patient, especially a child, is uncooperative or in undue distress even with procedural sedation, the emergency physician should cease removal efforts and refer the patient to an otolaryngologist; timing is dependent on the acuity of the presentation. Rates of operative intervention vary in published series. Studies’ case mix differences are probably responsible for the varying rates (from 5-33%) of reported need for surgical removal of otic foreign bodies.18,19

Inappropriately prolonged efforts at foreign object removal can result in wasted time, unnecessary patient discomfort, and high potential for complications as previously noted. Patient apprehension, untoward foreign body movement, or damage to the ear canal (including induction of edema) may prompt surgical intervention that would have been otherwise unnecessary.23

Otic foreign bodies are associated with many sequelae, but these are usually not serious. The most commonly occurring complications in pediatric series are external ear canal bleeding (approximately 16%), otitis externa (6%), and tympanic membrane perforation (2%).19 One large series suggests that otitis externa is significantly more likely in adults than in children, perhaps because of relative delays in seeking medical attention.24

After removal of the foreign body, the canal examination is repeated to ensure the lack of retained material and to evaluate otic anatomy. In cases in which the tympanic membrane is ruptured and the middle ear is at risk for infection, appropriate oral antibiotics are recommended. Common practice is to prescribe topical antimicrobial therapy to decrease the risk of external otitis; the meatus may be packed with an ear wick or ribbon gauze impregnated with a broad-spectrum antibiotic.4 Follow-up evaluation within 2 to 3 days is recommended for cases in which there was tympanic membrane rupture or in which foreign body removal was traumatic (to assess for external otitis).

Nose

The nose is perhaps the most common site for the insertion of foreign bodies by children. Perhaps because most people are right-handed, most nasal foreign bodies are right-sided.25 Compared with patients with ear canal foreign bodies, children with nasal foreign bodies tend to be younger (most commonly younger than 5 years).17

Nasal foreign bodies are less problematic than foreign bodies in other locations. ED removal is nearly always successful, and, with proper technique (e.g., care to avoid aspiration), serious sequelae are rare.25 Available data suggest that the overall risk that nasal foreign bodies will enter the bronchial tree is less than 0.06%.26 The infrequently encountered cases of intranasal magnets or alkaline button batteries, which may cause electrical or chemical burns and tissue necrosis, are exceptions to this rule of minimal risk.27

History

Although most patients seek medical attention within 24 hours, patients with nasal (versus otic) foreign bodies are more likely to have secondary symptoms and delays of 1 week.28 In fact, nasal foreign bodies may be asymptomatic, identified as incidental findings on imaging obtained for other purposes.

Patients seen in the ED with nasal foreign bodies usually have one of two histories. With the first type of presentation, the patient admits to or was seen placing an intranasal object. This is the most common history. Other patients have a constellation of signs and symptoms: purulent, unilateral, malodorous nasal discharge or even persistent epistaxis. These patients often are misdiagnosed and treated with antibiotics for supposed sinusitis. Unresolving sinusitis despite appropriate antibiotic therapy is an alert to the possibility of a nasal foreign body.28

Physical Examination

As with foreign bodies of the ear canal, preparing the patient (and the parents) for examination and subsequent removal attempts is an important component of the care plan. Because of risks of iatrogenic movement of the foreign body further posteriorly, children may need to be restrained to permit the examination. Physical examination sometimes can be delayed until after insufflation of the nares is attempted. The nasal mucosa is normally quite sensitive, and this sensitivity is increased by any infection or irritation. Examination is facilitated by provision of topical anesthesia and vasoconstriction to the nasal mucosa. Examination should include both nares, with adequate lighting and visualization with a nasal speculum. The emergency physician should note the presence of the foreign body and any secondary tissue damage. Necrosis of the nasal mucosa and septum may accompany button battery impaction.29 During the examination the emergency physician should take care not to dislodge or drive the foreign body posteriorly into the nasopharynx and risk aspiration. In some circumstances, it may be prudent to place patients in the lateral decubitus position, perhaps with additional Trendelenburg’s positioning, to help prevent aspiration of objects that are pushed into the posterior pharynx.

Diagnostic Strategies

Diagnostic imaging does not usually play a major role, although some have advocated for low-threshold use of plain radiography when button-battery foreign bodies are suspected.30 When intrasinus foreign bodies are suspected, CT can be helpful. Rarely, CT or MRI may be indicated to visualize suspected foreign bodies or their complications. The potential risk of MRI for detection of foreign bodies may become more relevant with increasing frequency of foreign bodies related to magnetic jewelry (i.e., nose rings and studs).31

Management

The emergency physician can remove most nasal foreign bodies. Although the avoidance of iatrogenic injury is paramount, the structures local to an intranasal foreign body are not as sensitive or easily damaged as structures in other body cavities (e.g., the ear canal) that may harbor foreign objects. As a result, the need for subspecialty consultation and operating room removal is rare.17,28

Occasionally, positive pressure applied to the patient’s mouth achieves rapid foreign body dislodgment while obviating the need for restraint, sedation, and other requirements attendant to more invasive removal techniques. This technique is a quick and safe primary intervention. The underlying principle is that a short burst of air blown into the mouth of a child, with finger occlusion of the nonobstructed naris, may force the foreign object out of the nose. Pretreatment with vasoconstrictive spray may improve chances of success.32 The insufflation, preferably applied as a “kiss” from a parent, can also be provided by a manual ventilation bag. The insufflation technique is quite useful, particularly in preschoolers who are likely to be uncooperative with other removal modalities. Many children can be instructed to take a deep breath and blow hard through their nose, as a parent closes the unaffected naris. An otherwise troublesome removal can be accomplished quickly and easily.33 Recent data suggest that the “kissing” technique’s success rate of nearly 50% was associated with additional advantages of decreased use of resources (e.g., time, anesthetics).34

When positive-pressure insufflation is not warranted or is unsuccessful, instruments and removal techniques may be required (see Figs. 60-4 and 60-5). Regardless of the method, the patient (usually a child) may benefit from some combination of restraint, sedation, and pretreatment with vasoconstrictive agents (e.g., nebulized racemic epinephrine) and anesthetic (e.g., benzocaine spray).32 Adequate illumination is essential. Necessary instruments include a blunt-tipped right-angle probe, suction catheter, and alligator forceps. The forceps are used when the foreign body is to be directly grasped, and the right-angle probe is used in an attempt to reach behind the foreign object and displace it forward. Other useful instruments include Fogarty (vascular) and Foley catheters; “specialized” balloon-tipped catheters also are available in many EDs (see Fig. 60-5).17 Magnets may be useful when the intranasal foreign body is part of magnetic jewelry.31 Suction is primarily necessary for removing purulent secretions and any blood that may obscure the field. In some cases, suction can be used to withdraw foreign bodies directly. Suction may be useful with hard-to-grasp objects or small soft objects not tightly lodged in place. Cyanoacrylate-tipped swabs may be useful in certain circumstances. As noted previously with respect to otic foreign bodies, there is insufficient evidence to draw definitive conclusions about this approach.

Airway

Although improved diagnostic and therapeutic techniques have markedly reduced fatality rates from foreign body inhalation, airway tract foreign objects still cause significant mortality and anoxic brain damage. One large-city series of ambulance-transported airway foreign body patients reports a 3.3% mortality (an average of one patient per month) in the prehospital phase alone.35

Alternatively, airway foreign objects can have a presentation that is less dramatic than acute respiratory distress and can go undiagnosed for years. Delay in presentation and correct diagnosis is, perhaps surprisingly, common. Only half of patients in one pediatric series of lower respiratory tract foreign body were seen within 1 day of aspiration; an additional 20% were seen during the first week, and another 20% were seen after a delay of more than 1 week.36 Another pediatric study identified a doubling of complication rates in patients who came to the hospital more than 48 hours postaspiration.37 Patients with uncharacteristic presentations may have unusual foreign body introduction mechanisms, such as ingestion or penetrating trauma.38 Patients with altered mental status from a variety of causes are at risk for occult aspiration, which may be difficult to diagnose. Even in large-series reports of aspiration, specific and reliable indicators of airway foreign body presence are elusive.39

The most common airway foreign bodies in one series were ingestible agents, primarily meats and medications.35 Airway foreign body series also identify pins, needles, jewelry, thermometers, pencils, and metal and plastic toys. The primary reason to characterize the type of airway foreign object is to determine the likelihood of radiopacity. Most airway foreign bodies are not visible with plain films.40 In one 8-year pediatric series of foreign body aspiration, the most commonly identified objects were nuts (59%) or other vegetable material (23%) not likely to be visualized on plain films. In another classic paper describing childhood asphyxiation with foreign bodies, nearly half of fatal choking cases were a result of food aspiration, with hot dogs (17%), candy (10%), nuts (9%), and grapes (8%) most prominent.41 In another report, more than 90% of pediatric aspiration cases were of organic classification (usually nuts).42

Airway foreign bodies are seen more commonly in pediatric patients.43 In one case series covering two decades, 75% of patients were younger than 9 years.42 Peak incidence of aspiration is in the second year of life, with a brisk decline after age 3.43 Mastication difficulty secondary to premature molar teeth contributes to pediatric food aspiration.36 Also, the fact that children explore their environment with their hands and mouth translates into aspiration of nonfood objects. In adults, the peak aspiration incidence is in the elderly.35 Some evidence suggests that adults are more likely than children to have nonfood items aspirated into the airway.44

Children and adults also differ with respect to anatomic location of aspirated foreign bodies. This is crucial because foreign body location plays a major role in determining associated morbidity or mortality risk. In adults, 75% of foreign bodies lodge in the proximal airways (larynx, trachea, main bronchi). In children, fewer than half of foreign objects are located proximally, with bronchial tree locations the most common.42

Foreign bodies can be located as proximally as the oropharynx, with retained intraoral bodies having been found in the medial pterygoid space.45 The foreign object can be slightly distal, causing airway obstruction at the laryngeal or subglottic level. Foreign body impaction at this level often is caused by inappropriately executed attempts to finger sweep an oropharyngeal foreign body.44 Subglottic foreign bodies are difficult to identify and may be associated with diagnostic delay in most cases.46 The emergency physician needs to be able to glean historical clues to differentiate epiglottitis, asthma, and laryngotracheobronchitis from subglottic foreign body.

Airway foreign bodies usually pass beyond the laryngeal inlet44 and may cause drastic obstruction. Unfortunately, tracheal foreign bodies have a surprisingly high incidence of lack of symptoms or worrisome clinical findings. Foreign bodies passing beyond the trachea are less likely to cause acute hypoxic crisis but can cause substantial respiratory embarrassment and can be difficult to remove. In adults, bronchial foreign bodies are found more often in the right bronchial tree. In one large series, 69% of bronchial foreign bodies were right sided.42 The preferential passage of foreign bodies to the right side of the bronchial tree is usually reported to be less common for children than for adults. Some series report roughly equal left-right distribution of lower airway foreign bodies.36 The explanation may be that whereas the carina is positioned right of the midtrachea in a third of children (and in 40% of infants), the proximal right bronchus is both wider and more steeply angled than the left.47 Foreign objects can be bilateral, with 3.6% of patients in one series having foreign bodies in the right and left main bronchi.42

History

Clinical presentation can range from chronic nonspecific respiratory complaints to acute airway obstruction.48 In most aspiration cases, foreign body presence is suspected after a thorough history. In the most dramatic cases, patients have a history of what is commonly termed the “cafe coronary.” The patient attempts to swallow a food bolus (usually meat) larger than the esophagus can accept. The bolus lodges in the hypopharynx or trachea. Often there is confusion over whether the patient is having a myocardial infarction or has an obstructing foreign body, but the conscious cardiac patient is able to speak. Patients with airway foreign bodies may have noisy breathing, inspiratory stridor, vomiting, and possibly slight hemoptysis.35

Some patients may give a history similar to cafe coronary, with resolution of major symptoms. These symptoms, known as the penetration syndrome, occur in half of patients aspirating and include a choking sensation accompanied by respiratory distress with coughing, wheezing, and dyspnea.42 Symptom resolution may result from the patient spontaneously clearing the foreign body by coughing. In some cases, coughing does not eject the foreign body completely, but rather impacts it in the subglottic region.44 The emergency physician should maintain concern for retained airway foreign object in cases in which the patient history is one of perceived foreign body followed by cough with incomplete (or even complete) post-tussive symptom resolution.

In a 20-year series of adult and pediatric patients with suspected foreign body aspiration, sudden onset of choking and intractable cough were present in half, with eventual foreign body identification.42 In addition to coughing and choking, stridor is a frequent component of an acute aspiration episode in patients of all ages.44 Symptom distribution is similar in adult and pediatric patients,42 but choking and wheezing appear more prominently in the pediatric literature. In one series of 87 pediatric patients with suspected foreign body, 96% had a history of a choking crisis.49 Wheezing is common, having been reported in up to 75% of patients aged 8 to 66 months with airway foreign bodies.36,43

Most patients aspirating objects have persistent symptoms (e.g., cough, wheezing, dyspnea) after manifesting penetration syndrome, but 20% have no ongoing symptoms.42 Many patients have a history of alarming symptoms followed by few ongoing complaints; the emergency physician should not dismiss aspirated foreign body from consideration in such patients. With sudden onset of dyspnea and odynophagia, an impacted subglottic object may be present. If the object is known to be sharp and thin, the emergency physician should suspect embedding between the vocal cords or in the subglottic region, with resultant partial obstruction.44

Other components of the history may provide clues to airway foreign body presence and location. Even when the history cannot be obtained directly or does not suggest aspirated foreign object, the emergency physician can infer foreign body presence in certain patients. Trauma patients in the ED with injured and loose teeth may have aspirated in the field or during emergency laryngoscopy for oral intubation.42 The incidence of airway aspiration of avulsed teeth or prosthetic dental appliances is low (0.5% of 1411 facial trauma patients), but both the initial trauma and subsequent airway management pose risks for airway embarrassment owing to lodged dental matter.50 Besides the intubated or obtunded patient with only indirect historical evidence of aspiration, conscious and alert patients may not give a direct history of aspiration owing to lack of dramatic airway symptoms or remoteness of the aspiration event and secondary problems (e.g., pneumonia). In some cases, such as penetrating trauma or blast injuries, the patient may be unaware of the potential for aspiration and not attribute symptoms to this entity.40 Patients aspirating needles may have minimal or no symptoms, with chronic hemoptysis or odynophagia the only manifestation of these or similar foreign bodies.42

There is conflicting evidence regarding the role of neurologic disease in aspiration. Patients with deficits may be unaware or unable to report problems such as denture displacement; this inability has been associated with disastrous results in the case of airway obstruction from dental hardware.51 Neurologic impairment may result in atypical or absent histories in cases of foreign body aspiration.40 Reports of adult42 and pediatric49 series have identified little role, however, for neurologic impairment in foreign body aspiration. An atypical history is a concern in neurologically impaired patients, but the problem of foreign body aspiration with atypical history is uncommon in this patient population.

The child with respiratory difficulty after eating can represent a diagnostic dilemma. Children with stridor or other respiratory symptoms may have esophageal bolus impaction. The pediatric trachea is soft, especially posteriorly, and may be compressed by a large esophageal body pressing anteriorly on the trachea. In addition, the trachea itself may be displaced anteriorly and kinked, causing a partial obstruction. Fever and localized infection may indicate bony aspiration (e.g., into the piriform fossa) that may occur when bone-containing foods are fed to very young children.52 Unfortunately, missed esophageal foreign bodies in children can result in long-term, yet mistaken, treatment for asthma (owing to wheezing and stridor from fistula formation).53

Physical Examination

Cyanosis is present in 10% of patients, and coughing, audible wheezing, or overt respiratory distress occurs in 25 to 37% of patients with aspirated objects.42,43 Unilateral diminution of breath sounds, when present, is a useful identifier of aspirated foreign body.48 Patients may be stridorous or hoarse with upper airway foreign objects, and sternal retractions may be noted in patients with intratracheal foreign bodies.35 More than half of children in one series had initial oxygen saturation values of 95% or lower.42 Patients with secondary infection may have fever.

Oropharyngeal examination may reveal a foreign body posteriorly or “donor sites” of fractured teeth. The examination should include a search for fractured or missing dental prostheses, which sometimes can be lodged in pharyngeal areas for days and can account for sudden deterioration in status when the airway becomes occluded, as can occur after coughing.51 Oropharyngeal examination frequently can be augmented by indirect or direct laryngoscopy or nasopharyngoscopy, but these procedures should be performed only if the emergency physician judges that procedural stress does not pose undue risk of airway compromise. Furthermore, laryngoscopy or nasopharyngoscopy should be undertaken only if definitive airway management equipment and expertise are readily available. The advantage of these modalities is that they allow excellent visualization of the proximal airway, which is important diagnostically and therapeutically. Indirect laryngoscopy can prove useful in detection of radiolucent structures.

Assessment of the neck may reveal accessory muscle use. Tracheal palpation may reveal a thud, indicating movement of a mobile foreign body against the tracheal wall. Abnormal inspiratory sounds may be heard on tracheal auscultation.44 Coughing may result from local irritation caused by bronchial foreign bodies. Localized or apparently generalized wheezing is frequently auscultated in patients with lower respiratory tract foreign bodies.43 The emergency physician should keep in mind the dictum that “all that wheezes is not asthma.” If a mainstem bronchus is completely obstructed, breath sounds are absent on the involved side. Occasionally a foreign body acts as a one-way valve, allowing air into the lung during inspiration but permitting none to exit during expiration. The involved lung becomes hyperexpanded, which may be detected as hyper-resonance to percussion.

Diagnostic Strategies

In the stable patient, plain radiography of the neck and chest remains the mainstay of airway foreign body imaging.40 Air trapping may be visible when inspiratory and expiratory films are compared.43 Other potentially useful imaging techniques are fluoroscopy, CT, and MRI, although bronchoscopy and microlaryngoscopy (with an operating microscope) remain the ultimate diagnostic modalities.43

A normal radiograph cannot rule out an aspirated foreign body in a patient with a suggestive history. Studies of series of patients who underwent endoscopy for suspected foreign body aspiration demonstrate the mediocre sensitivity and specificity of plain x-ray films.42,48,49 X-ray findings are indirect in most cases; radiopaque foreign bodies were found uncommonly (less than a fourth of patients in one series).54 This series included foreign bodies in the upper airway (at the level of the trachea); plain radiographs in these patients were frequently negative.49 If doubt exists as to the radiopacity of the suspected foreign body, and if the patient has brought a piece of the object, it may be tested for radiodensity by placing it over the shoulder during taking of the radiographs. Specific findings on plain radiography are categorized as direct (i.e., identification of the foreign body itself) or indirect (e.g., hyperinflation). Direct foreign body identification is relatively uncommon.44 When subglottic foreign body impaction is suspected, plain soft tissue radiographs of the neck are the best initial step, provided that they are performed under the close supervision of a physician trained in provision of airway management. In some of these patients, plain radiography may definitively show an intratracheal foreign body and can provide a rapid diagnosis.44

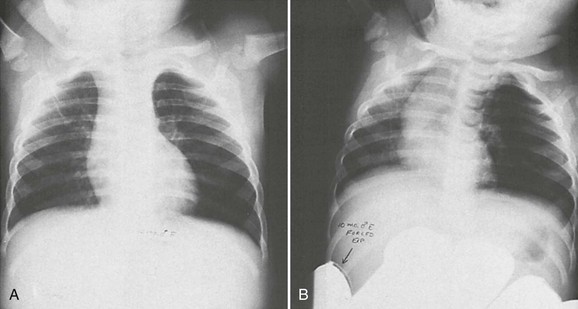

Indirect or secondary signs, such as narrowing of the subglottic space from an embedded foreign object, are an important aid in foreign body radiography.44 Air trapping and atelectasis are the most common early clues to airway foreign body presence, with bronchiectasis and bronchial stenosis developing later.40 In air trapping, a comparison of inspiratory and expiratory films shows a flat, fixed diaphragm on the involved side, and the heart and mediastinum shift to the uninvolved side during expiration (Fig. 60-6). In one pediatric series, air trapping was found in 90% of patients with lower airway foreign bodies, but it appears that the indirect signs of airway foreign body are easily missed on initial x-ray readings.36 The small caliber of the airways may explain the relatively higher frequency of air trapping in children compared with adult patients.42 If obstruction becomes complete, the involved lung becomes atelectatic; patients with persistent atelectasis should have foreign objects considered as the explanation. An additional indirect radiographic sign of more proximal foreign bodies is prevertebral swelling or soft tissue emphysema seen on neck films.40

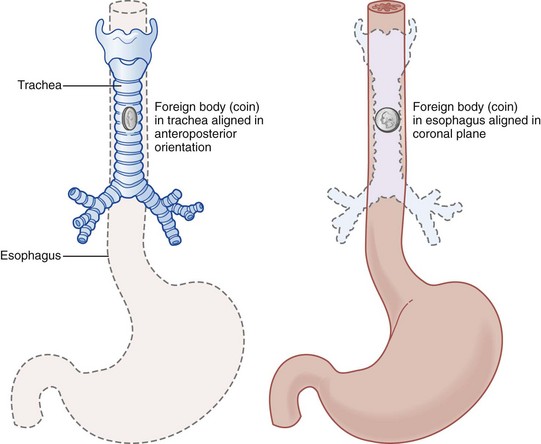

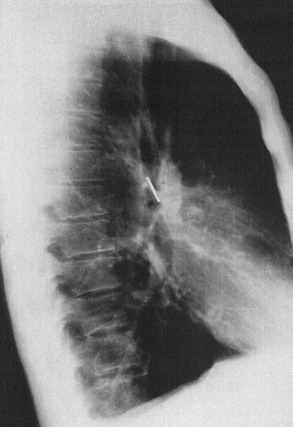

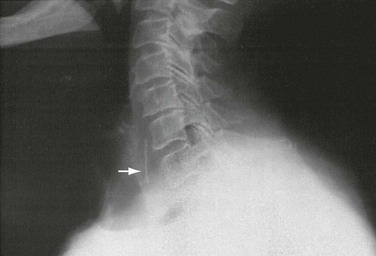

When a foreign body is seen on the chest radiograph but its exact location (airway or esophagus) is in doubt, the anteroposterior orientation of the object may help (Fig. 60-7). Esophageal foreign bodies usually are oriented in the coronal plane, and airway objects are oriented in the sagittal plane (Fig. 60-8). X-ray films also can provide useful information by showing whether the object is within or outside of the tracheal air column (Fig. 60-9).

Figure 60-9 Lateral x-ray study of neck shows foreign body (chicken bone) in esophageal soft tissue shadow (arrow).

Fluoroscopy was used historically, but has been largely supplanted by advances in bronchoscopy. Fluoroscopy has identified air trapping, but one case series reported a relatively low 77% sensitivity for foreign body presence using air trapping.36,40 CT, especially helical, is useful in evaluating patients with suspected airway foreign bodies when plain films are negative. Even when an aspirated object is radiolucent, and often when the object cannot be identified by standard thoracic CT, helical CT has visualized the foreign body when it is of greater density than surrounding tissues. Helical CT can obviate the need for diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy, allowing direct progression to therapeutic rigid bronchoscopy for foreign object retrieval. CT also can be useful in delineating specific anatomic changes caused by foreign bodies. MRI may be useful in cases of aspiration of nuts, especially in children. The high fat content of the nut translates to relatively easy visualization on MRI.40

Management

Management of an airway tract foreign body is removal, which generally leads to rapid recovery of the patient.42 The emergency physician can accomplish removal in some patients. When the foreign object is distal to the oropharynx, however, subspecialty consultation is the safest and most expeditious means for foreign body removal. In rare cases, even oropharyngeal foreign bodies (such as small needles) may necessitate subspecialist consultation and operative removal.55 As a general rule, early bronchoscopy in any patient with a suspected foreign body is key to reducing morbidity and mortality, and the role of endoscopic management remains important given limitations of other diagnostic methods.43,48 Recent pediatric data suggest that performance of bronchoscopy within 24 hours of initial ED presentation (as compared with later bronchoscopy) reduces complications by half.37

Some maneuvers to remove foreign bodies acutely are accomplished without direct visualization. These attempts may be directed at the proximal or distal respiratory tract. Proximal foreign body removal without direct visualization is attempted with the finger sweep, but this technique is losing favor in pediatric and adult patients. In infants, the larynx is higher, at the level of the fourth cervical vertebra; by age 4 years, it is at the C5-6 level. Blind finger sweeping has resulted in conversion of partial to complete airway obstruction when objects are displaced into the subglottic space. Finger sweeping also is less preferable in adults; abdominal thrusts and back blows are safer and at least as efficacious.44 These procedures produce increased intraluminal pressure in the trachea and force objects out into the pharynx, from which they are easily removed.56

If indirect efforts fail to remove foreign bodies from patients in extremis, direct laryngoscopic visualization during intubation may reveal a proximal foreign object that can be removed with Magill forceps.35 If a foreign body is not visualized on laryngoscopy, the emergency physician may choose to intubate the patient. Intubation may force the foreign body distally, especially if the endotracheal tube tip is passed beyond the carina. Placement of the endotracheal tube into the right mainstem bronchus may displace the foreign body into the right bronchus, allowing oxygenation and ventilation through the left-sided pulmonary tree when the endotracheal tube is withdrawn back to normal position proximal to the carina. In cases in which intubation fails because of positioning of the foreign object, surgical cricothyrotomy (needle cricothyrotomy in young children) is indicated. Cricothyrotomy may bypass proximal obstruction and provide sufficient oxygenation to bridge the time gap to definitive care by surgical subspecialists.

Patients who do not require immediate intubation or cricothyrotomy for complete airway obstruction may require airway management for other indications. These patients may have poor oxygenation or may require assisted ventilations during transport to surgery. In either case, if airway obstruction is not too proximal or too complete, the emergency physician should consider placement of a laryngeal mask airway. The laryngeal mask airway offers easy airway access, excellent visualization, and safe respiratory management during bronchoscopic procedures. The laryngeal mask airway allows use of larger bronchoscopes than those used in intubated children. Especially in pediatric patients requiring bronchoscopy, the laryngeal mask airway may be an appropriate airway.42

In noncritical situations, the only airway foreign objects generally amenable to emergency physician removal are those in the oropharynx, which are best removed by forceps under direct laryngoscopic visualization performed after administration of topical anesthesia. Care should be taken when foreign objects appear to be impaled in the oropharynx because postremoval hemorrhage can occur. Also, special care should be taken to prevent posterior displacement of oropharyngeal foreign objects or dropping of incompletely grasped foreign bodies into the airway. These complications are risked in patients who are uncooperative; in these patients, consultation for removal in the operating room is the best course. Removal of a laryngeal foreign object, even with general anesthesia, can be dangerous. Risks include hemorrhage, laryngeal trauma, and airway obstruction from the mobilized foreign object; subspecialty consultation also is indicated for laryngeal foreign body removal.44

The management decisions for endoscopic evaluation and treatment depend on the clinical presentation. An emerging standard is initial use of rigid bronchoscopy when there is time-critical airway obstruction, with flexible instrumentation used for diagnostic purposes in less acute patients.43 The emergency physician may have requisite expertise to perform flexible bronchoscopy in occasional low-risk cases, but consultants may have broader experience, as well as facility with potentially useful adjuncts such as cinefluoroscopy.57 In patients for whom overall clinical suspicion for the presence of a foreign body is reduced, fiberoptic bronchoscopy may be indicated, but rigid bronchoscopy is the optimal first step when clinical suspicion is high.36 Foreign body removal usually is achieved with rigid bronchoscopy with the patient under general anesthesia, but in unusual circumstances flexible bronchoscopy with local anesthesia may suffice for foreign body location and removal.42

Even after foreign body removal, sequelae may occur. Airway fish bones, even after removal, can cause deep tissue infection, such as cervical spondylodiskitis.58 A patient with an airway foreign body should be observed for development of sequelae, with postdischarge follow-up within a few days for reassessment. In pediatric patients, education should focus on preventive efforts to reduce the likelihood of a repeat aspiration episode.

Gastrointestinal Tract

Foreign bodies in the gastrointestinal tract can be seen in all age groups, although most cases occur in pediatric patients.59 There is no requirement for predisposing anatomic or pathologic conditions. Series have noted, however, that in addition to younger persons, those at highest risk include edentulous, incarcerated, and psychiatric patients.60,61 Higher risk is also present in cases in which chemical and/or electrical mucosal injury is likely (e.g., button battery or magnet ingestions).62,63

Perforation occurs in approximately 3% of cases and most frequently involves the esophagus or the ileocecal region.64 Because ingested objects are expected to pass spontaneously in the vast majority of patients with normal anatomy, initial management is usually expectant, with radiographic and stool follow-up to confirm passage.64 Direct foreign body removal through surgical intervention is usually unnecessary, although some centers pursue early operative intervention for impacted esophageal objects including coins.65 In pediatric series, endoscopy—including esophagoscopy, laryngoscopy, and anoscopy—tends to be successful in removing the foreign body in nearly all cases.65,66 Endoscopic removal of esophageal foreign bodies also allows for simultaneous performance of mucosal biopsy, which may be useful in pediatric patients brought to the ED with esophageal food impactions (the majority of these children will have correctable abnormalities identified on biopsy).67 Early endoscopy should usually be undertaken in cases of potential toxicity (e.g., button battery ingestion), altered anatomy (e.g., prior abdominal surgery), or sharp foreign bodies.

Pharynx and Esophagus

Foreign bodies lodged in the pharynx and esophagus are usually a sharp object (e.g., fishbone) that is impaled in the wall of the pharynx, hypopharynx, or esophagus or a larger bolus, usually a coin or food, that cannot pass beyond the anatomic points of esophageal constriction. Pediatric series analyzing both witnessed and unwitnessed esophageal foreign body ingestion report that coins are the most common culprit, making up over half of ingested foreign bodies in typical series.65,68 Esophageal constriction locations, where foreign objects tend to lodge, are (1) the proximal esophagus at the level of the cricopharyngeal muscle and thoracic inlet or, radiographically, the clavicular level; (2) the midesophagus at the level of the aortic arch and carina; and (3) the distal esophagus just proximal to the esophagogastric junction or, radiographically, a level two to four vertebral bodies cephalad to the gastric bubble. Foreign bodies may lodge at any level of the esophagus (or remainder of the gastrointestinal tract) with abnormal anatomy. The complication rate for esophageal foreign body ingestion is estimated at less than 2%, but the sequelae can be severe. Complications become more likely with increasing impaction time and include esophageal erosion or perforation, tracheal compression, mediastinitis, esophagus-to-airway or esophagus-to-vascular fistulae, spondylodiskitis, extraluminal migration, abscess development, and formation of strictures or false esophageal diverticula.65,69–71

History

A useful history is usually available from the patient or caregivers. Children are particularly likely to have esophageal foreign bodies. The object most often encountered is a coin.65,68 Other common objects are food, toys, bones, batteries, wood, and glass.72 In situations in which the history is unclear, the emergency physician should consider an ingested foreign body in the differential diagnosis of atypical chest pain.73

Esophageal rupture is a particular risk from the button (disk) battery.3 These batteries cause pathologic changes through pressure, electrical current, leakage of corrosives, or heavy metal poisoning.59 Batteries containing potassium can produce liquefaction necrosis, and those containing mercury can cause mercury poisoning.74 The identification of button batteries has both prognostic and therapeutic ramifications; esophageal button battery impaction is an indication for prompt endoscopic intervention.59 Although not as likely as button batteries or sharp foreign bodies to cause esophageal rupture, practically any ingested foreign body (e.g., meat) can cause rupture if patients vomit repeatedly after impaction.75

An ingested object in place for longer than 24 hours is more likely to cause mucosal erosion. Management plans for ingested bodies are different when the objects have been in the gastrointestinal tract for a long duration.72 Children usually are brought to the ED within 6 hours of foreign object ingestion. The most frequent presenting symptoms are dysphagia, drooling, retching, and vomiting. Pain, usually odynophagia, may be the major complaint. Anorexia, wheezing, or chest or neck pain also may be present. Patients may complain that they can feel the object in the throat or chest and are unable to pass it any farther. The victim often is able to localize the foreign body accurately, particularly in the upper esophagus, and should be asked to indicate the level of obstruction. Drooling is consistent with high-grade obstruction. Patients rarely have complaints of shortness of breath or air hunger, though when present, a large foreign body in the esophagus impinging anteriorly, compressing the trachea, should be suspected. Infants and children may experience coughing, choking, and significant respiratory compromise from foreign bodies lodged in the upper esophagus.65

Patients may manifest late sequelae. Foreign bodies serving as a nidus for infection result in complaints (e.g., fever) consistent with the infectious process.65 Signs of mediastinitis indicate esophageal perforation. Perforation of the esophagus with erosion into the vasculature or pulmonary tree can result in presentations ranging from hemoptysis to pulmonary abscess to life-threatening hemorrhage.76,77

The history should include any known esophageal anatomic abnormality or prior instrumentation. A patient with a history of esophageal stenting should be considered to have stent migration when the history is dysphagia. Migration typically occurs within the first week of placement but has been reported up to 1 year after initial placement.78

Physical Examination

Subcutaneous emphysema found by neck palpation indicates probable esophageal perforation. Drooling and inability to handle secretions are secondary indicators of esophageal impaction; wheezing can occur if there is airway compression.65

Diagnostic Strategies

Given the limitations of clinical presentation and examination in excluding a foreign body, radiography is routine and contributes to diagnosis and management in about half of cases.79 The initial step is generally a posteroanterior (PA) and lateral chest radiograph and lateral cervical spine x-ray study using soft tissue technique. The primary utility of plain radiography lies in detection of radiopaque objects, although some series report that retrospective review of lateral neck x-ray films identifies indirect signs (e.g., soft tissue swelling) in most patients with proximal aerodigestive tract foreign body.79 Overall, the sensitivity of plain radiography for detection of esophageal foreign bodies is relatively poor80; however, there are case reports of plain radiography identifying metal foreign objects missed on direct (including endoscopic) examination.81 In patients who are transferred to the ED from an outlying hospital, repeat radiography may be useful to assess whether the foreign object has passed into the stomach in the interval since prior films (see Fig. 60-10).72

Esophageal foreign objects usually align themselves in the coronal plane and are posterior to the tracheal air column on lateral view. Coins in the esophagus lie in the coronal position in virtually all cases because the opening into the esophagus is much wider in this orientation.72 Certain common foreign bodies are not radiopaque; for example, fish and chicken bones are frequently ingested, are difficult to visualize directly or radiographically, and often scratch the esophageal mucosa. Plain films of the neck and chest have a sensitivity of roughly 25% for impacted fish bones.82 Although some studies suggest that technique variation improves fish bone detection, plain x-ray examination remains insufficiently sensitive as a means to rule out these foreign bodies.83 Studies suggest that plain films are false-negative in at least 30 to 55% of cases and false-positive in about a fourth of cases.82

When plain films fail to visualize foreign bodies and suspicion remains high, one option is contrast esophagography, which can be useful with radiopaque and sometimes with radiolucent foreign bodies.72,84 If perforation is not a concern, barium may be used as the contrast medium because it provides higher-quality images. If an esophageal leak is suspected, water-soluble contrast solution should be used; a barium follow-up study may be considered if the initial contrast study is equivocal or suspicion remains high. When initial contrast films are not definitive, patients may be asked to swallow a contrast-soaked cotton ball, which may localize the foreign body by lodging proximal to the object. Contrast studies, even performed with barium, have limitations when the suspected object is an impacted bone.80 In one series using barium-soaked cotton balls, false-positive and false-negative rates were 27% and 40%, respectively.85 Barium swallow yields better results but risks aspiration and coats the object and esophagus, reducing effectiveness of subsequent endoscopy.

CT scans with coronal and sagittal reconstructions are useful in identifying foreign bodies or more completely characterizing objects seen on plain films.86 CT has been recommended as the primary diagnostic modality because it can give information about foreign body size, type, location, and orientation with respect to other anatomic structures.60,86 In one study, non–contrast-enhanced CT interpreted by resident physicians detected all impacted bony foreign bodies found by esophagoscopy; the one false-positive result was caused by esophageal calcification, and no false-negative results occurred. Overall, CT use reduced the incidence of negative esophagoscopies. This study portends a potentially important role for CT in imaging of impacted bony foreign objects.72 CT also can assist with identification of complications. Also, CT may be used in patients with positive plain films and negative esophagoscopy to search for objects that have migrated from the intraluminal to extraluminal space.60

A relatively inexpensive and noninvasive modality reported to be useful in detection and characterization of metal foreign bodies is the hand-held metal detector. Use of a commercial hand-held metal detector (Super Scanner; Garrett Security Systems, Garland, Tex.) has been studied in large series of adult and pediatric patients with suspected esophageal metallic foreign bodies. Early data reported no complications, with positive and negative predictive values approximating 90 to 100%.87 More recent series confirm high positive predictive value but find much lower negative predictive value.88 The hand-held metal detector does appear to easily detect aluminum foreign bodies missed by radiography. Its use avoids time, radiation, and costs associated with radiography. Especially when results are positive and indicate a foreign body below the diaphragm, metal detector use may obviate the need for radiography in patients with suspected coin ingestion.88

Management

Management of esophageal foreign bodies depends on many factors. With an esophageal food bolus or coin, the emergency physician may be able to provide complete management. With sharp objects, displaced esophageal stents, or impacted button batteries, more invasive management is necessary.72 Management strategy depends on the nature of the foreign body, the length of time the object has been lodged, and the expertise and experience of the clinicians managing the case.72 In addition, the patient’s age and prior medical and surgical history may be relevant.66 The overall success rate for nonsurgical removal of objects from the esophagus is greater than 95%.85

The first basic strategy for esophageal foreign body management is applicable only if the object is known to be an impacted food bolus. In these cases, pharmacologic maneuvers may be tried to move the bolus into the stomach. Glucagon (0.5 to 2 mg) given intravenously has been used to relieve distal food obstructions. The drug acts by lowering the smooth muscle tone at the lower esophageal sphincter without inhibiting normal esophageal peristalsis. This mechanism is theoretic, and a critical assessment of the relevant evidence concluded that data supporting glucagon use for esophageal impaction were unconvincing. Benzodiazepines appear to have contributed to glucagon’s success as documented in at least one report.89 Although it remains reasonable to try glucagon, the drug should be given slowly; if glucagon is given too rapidly there is theoretic risk that vomiting could cause rupture of an obstructed esophagus. Other pharmacologic agents have been used with mixed success. Gas-forming agents have been used, and although supporting evidence is sparse, some investigators suggest that administration of these agents alone or in combination with glucagon be the procedure attempted first. Patients who report chest pain at presentation should not be given gas-forming agents because these patients may have esophageal perforation. Two other agents used for distal food bolus impaction, which are probably not as useful as glucagon, are nitroglycerin and nifedipine. Both of these agents have a relaxing action on the lower esophageal sphincter and are safe and roughly equally (if only marginally) effective maneuvers for therapy of impacted food bolus. A last approach, enzymatic degradation of an impacted meat bolus by use of the proteolytic enzyme papain, has fallen into disfavor because of risks of esophageal perforation.

The preferred strategy for esophageal foreign body removal is endoscopy. Flexible endoscopy does not require general anesthesia, can be performed in a sedated (nonintubated) patient, and may be diagnostic and therapeutic in the case of foreign bodies such as coins.66 The high overall success of endoscopy has prompted some experts to recommend that patients with symptoms starting within 48 hours of ED presentation be taken directly to endoscopy if no suspected complication is evident.72

The final strategy for active foreign body removal, bougienage, involves pushing the foreign object into the stomach. Strict criteria determine eligibility for this procedure, which generally is not performed by the emergency physician. Compared with endoscopy, bougienage appears to be at least as safe, and much more time- and cost-efficient.90 Although patients’ eligibility for bougienage may be limited by factors such as presentation delay, when performed, the procedure appears to be successful in up to 95% of attempts.90

The fifth approach, expectant management hoping for spontaneous foreign object passage into the stomach, is often successful. This approach is best suited for patients seen within 24 hours of ingestion who have a radiographically identified “safe” object (e.g., small coin) in the distal esophagus.72 The button battery is associated with specific expectant management issues. If a disk battery has been ingested, its location must be ascertained, with immediate removal performed if it has lodged in the esophagus. If the button battery has passed distal to the esophagus, the patient can be observed, with follow-up radiography to confirm spontaneous passage through the gastrointestinal tract.91

Stomach and Bowel

Foreign bodies that reach the stomach (Fig. 60-10) rarely cause major difficulties, although problems such as perforation and infection (e.g., after occult fish bone ingestion) may occur.92 Although significant sequelae are more likely after ingestion of sharp foreign bodies, clinical problems may occur even with ingestion of blunt objects. Observation and expectant management are usually appropriate91 because ingested foreign bodies reaching the stomach usually are propelled by peristalsis through the length of the gastrointestinal tract, with expulsion in a few days. Objects may pass beyond the esophagus and still become impacted, however, most often at the gastric outlet or the ileocecal valve, although complications can arise at any point throughout the intestinal portion of the gastrointestinal tract.93,94 If the foreign body is a bezoar, a mass of undigestible food or nonfood material, there may be a palpable mass on abdominal examination. Otherwise, the physical examination is relatively unhelpful, only rarely revealing indirect evidence of foreign body presence or complications.

History

Signs and symptoms of intraluminal objects range from none to vague abdominal pain to obstruction or perforation-associated peritonitis.94 Most patients have a specific history of ingested items, however, or the circumstances indicate the likelihood and character of an intestinal foreign object. Occasionally, emergency physicians encounter patients with psychiatric or secondary-gain reasons for foreign body ingestion.

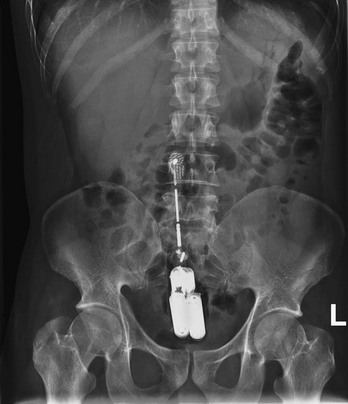

Hiding of illicit drugs is an important motivation for foreign body ingestion. Rupture of these drug-containing packages, especially when cocaine is involved, can result in rapid and lethal consequences. Less often, packages can cause bowel obstruction. Even when obstruction is not present, vomiting may be reported. Body packing, which entails systematic gastrointestinal tract placement of previously prepared drug packages (Fig. 60-11), should be clinically differentiated from body stuffing, which denotes hurried ingestion of hastily prepared packages in the face of imminent police presence. Body stuffers are more likely to experience toxicity because of the poor packaging of drugs and are less likely to have positive plain radiography findings.95 Drugs most often seen with body packing or body stuffing are cocaine and heroin, with amphetamines and cannabinoids seen less frequently.

Figure 60-11 Radiograph of a patient after body packing. Note the appearance of previously prepared drug packages.

Another important component of the history is medical implants in the gastrointestinal tract. Dental implants can migrate and cause complications in the distal gastrointestinal tract.96 Expandable esophageal stents migrate in some patients, and biliary stents have also been become malpositioned with resulting complications.97

Patients with gastrointestinal tract foreign bodies should be asked about history possibly related to bezoar presence. A habit of chewing hairs can result in trichobezoars, which infrequently extend from the stomach into the small intestine as a “tail” (Rapunzel syndrome). Phytobezoars (composed of vegetable matter) and lactobezoars (from milk curds) also have caused complications, usually in the stomach.98 Infants with lactobezoars from undigested formula may have a history of prematurity and often are receiving formulas that have a high casein-to-whey ratio. Other bezoars may be composed of infectious material (e.g., fungal bezoars) or inorganic substances (e.g., lithobezoars).99

Other specific intestinal foreign bodies, previously mentioned in the discussion of esophageal impaction, are important in the distal gastrointestinal tract. Button batteries can rupture in the intestines, and fish bones have penetrated through the gastric mucosa. Ingested toothpicks can lodge in the bowel wall, causing gastrointestinal complications and erosions or compression of nearby structures.86

Diagnostic Strategies

The initial imaging modality is plain radiography, which is often diagnostic (see Figs. 60-10, 60-12, and 60-13). Even when suspicion is low, radiography can identify foreign bodies as the explanation for symptoms.101 Two-view plain radiography has proved useful for situations ranging from coin ingestion to body packing (see Figs. 60-10 and 60-11). Plain radiography is positive in approximately 90% of body packers but is nearly always negative in body stuffers and is usually negative in patients who have ingested crack vials.95 Plain radiography usually identifies drug packets, but false-negative results do occur, and follow-up contrast radiography or CT is recommended.102 Ultrasound has been reported useful in drug-packet cases in which plain radiography is nondiagnostic, but this modality is most helpful when results are positive (i.e., negative results are insufficient to rule out ingested packets).103

Figure 60-13 Radiograph of a child after ingestion of a nail (which ultimately passed after observation).

Contrast-enhanced upper gastrointestinal radiography has intermediate success in patients with suspected body stuffing or body packing. Contrast administration also has proved useful in outlining bezoars. CT can identify foreign bodies in the stomach and intestines and can help diagnose package ingestions in body stuffers. In these patients, contrast-enhanced CT outlines the bag containing the illicit drug; contrast administration also can help by identifying air trapped in the package. Some data suggest that with the advent of multidetector CT, contrast may be unnecessary to diagnose drug-containing packets; these results are preliminary and based on imaging of phantoms rather than actual patients.104 Even contrast-enhanced CT has been found to occasionally produce false-negative results in detection of drug packages.98 CT also has proved useful in determining whether complications of foreign body perforation are present.83

Management

The general rule for the management of gastric or intestinal foreign bodies is observation, although some centers favor early endoscopy and report this approach to be nearly universally successful.68 Management decisions are based in part on the nature of the ingested object. Blunt objects can be expected to pass easily through the bowel, with expulsion verifiable by stool collection and examination. If there is particular concern, serial radiographs may be obtained after 5 to 7 days.59 Sharp objects may be recovered by means of fiberoptic gastroscopy, although they traverse the gastrointestinal tract without incident in 90% of cases.66 Early removal generally is required for objects wider than 2 cm because they do not pass the pylorus or longer than 5 to 6 cm because they do not clear the duodenal sweep.59 Overall, surgery is required in less than 1% of intestinal foreign body cases, but there will be cases (e.g., bowel obstruction) in which clinical circumstances prompt early operative intervention.93,94 When chosen, observation should be continued until (1) the object is found in the patient’s stool; (2) the object causes bowel obstruction or perforation, necessitating immediate surgical intervention; or (3) the object shows no evidence of progression through the gastrointestinal tract on two radiographic examinations performed 24 hours apart, indicating impaction and need for active removal. In some cases the identity of the foreign body dictates management. In a body packer or body stuffer, regardless of external (i.e., law enforcement) pressures, the emergency physician should perform only interventions justified medically as reasonable steps to prevent injury from the ingested object or substance. If urgent drug package retrieval is unnecessary, the patient should be admitted for close observation for package passage or signs of toxicity. Monitoring of drug levels can be helpful. Usually the package passes through the gastrointestinal tract spontaneously. This passage can be facilitated with polyethylene glycol solution, laxatives, or both.

Immediate removal of drug-containing packages should be considered if the patient develops intestinal obstruction or drug intoxication. Classic teaching, citing risks of package rupture and drug toxicity, contends that endoscopic removal of cocaine-containing packages is never indicated.105

Button batteries represent another foreign body type with specific management implications. Intact batteries ingested into the stomach can be observed without the immediate removal necessary in cases of esophageal impaction. Repeat radiographs should be taken the next day to ensure movement of the battery into the intestinal tract, with films every 3 to 4 days thereafter to confirm continued distal movement. As with illicit drug–containing packages, administration of polyethylene glycol solution may speed distal movement. If the foreign body has not been passed after the first few clear-liquid stools, repeat radiography may identify the battery in the rectum, where it may be digitally evacuated.91 Surgery is indicated for failure of the battery to progress, for radiographic signs of battery rupture, or for development of symptoms such as abdominal pain.72 Endoscopy is increasingly reported to be useful for gastric button batteries, with success in 14 of 16 cases in one series (the other two batteries were endoscopically moved into the intestine and then passed spontaneously).68 Available evidence is insufficient to confirm the usefulness of adjuvant medical therapy (e.g., steroids, antireflux agents, prophylactic antibiotics) in cases of button battery ingestion.106

Management of bezoars depends on type and location. Dietary therapy, endoscopic removal, and enzymatic dissolution frequently are used.94 For some bezoars, specific therapy exists. Infants with lactobezoars should be changed to elemental diets and observed because most cases resolve without surgery.

Rectum

Most anorectal foreign bodies result from retrograde introduction, typically as a result of sexual practices that patients might be reluctant to discuss. The history may also be difficult as a result of mental disorders, found in over a third of patients with rectal foreign bodies in one 8-year series.107 Prompt diagnosis is crucial because delay in definitive treatment is strongly associated with complications.

Patients with anorectal foreign bodies are often hesitant to give accurate histories. Studies have found that many patients with self-introduced anorectal foreign bodies do not initially admit to insertion, but rather report anal pain or simply constipation (which is in fact the most common complaint).107 Other complaints include rectal pain, bleeding, or inability to void when large objects impinge on the urethra. History also may be lacking in body packers, who may have toxicity symptoms; fatal cardiovascular collapse can occur with ruptured cocaine packages.

It is possible for ingested food or objects to lodge in the rectum after passing through the proximal gastrointestinal tract. Rectal foreign masses of fish bones have been noted in many patients, all of whom strenuously denied transanal insertion, and in one series (characterized by a high proportion of mental patients) oral ingestion accounted for nearly half of the rectal foreign bodies.107 If a patient admits to transanal foreign body placement, the emergency physician might gain more accurate information about size, shape, and physical characteristics to plan imaging and extraction. The duration for which the object has been in the anorectum has implications for mucosal failure and rupture.

Diagnostic Strategies

The foreign body may be detected on a plain abdominal radiograph (Fig. 60-14). Plain films were diagnostic in nearly half of patients in one series and are recommended as the initial imaging technique. An important secondary finding is free intra-abdominal air secondary to anorectal perforation. If the object is not visualized on plain films, a contrast study can be performed, with care taken to minimize hydrostatic pressures on potentially compromised mucosa. Water-soluble contrast should be used if perforation is suspected. Specialized imaging, such as CT, is not usually part of the imaging workup but may be indicated if complications are suspected.

Management

Using patience and judicious sedation and analgesia, the emergency physician often can remove rectal foreign bodies. Surgical intervention may be necessary on occasion, and in fact has been required in the majority of patients in some series.108 Depending on the nature of the foreign body and the presence of damage or perforation of the rectal wall, transanal removal (with or without sedation and local anesthesia) is successful in roughly half of patients, with the remainder requiring general anesthesia.107 Some advocate early triage of patients for operating room removal if ED foreign body extraction carries undue risk of anal sphincter injury.109 The emergency physician should not attempt to retrieve objects that pose a high risk for rectal injury because of sharp edges or the likelihood of dangerous breakage (e.g., light bulbs).

When digital extraction fails, the emergency physician should attempt to use an anoscope or small vaginal speculum to visualize the foreign body. Ring forceps are placed through the visualizing apparatus to grasp and remove the object. Sometimes the mucosa may become tightly adherent to the distal end of the foreign body, creating a vacuum that prevents object withdrawal. Passage of a Foley catheter beyond the foreign object (sometimes through a rigid sigmoidoscope) with proximal air inflation usually breaks the vacuum and permits retrieval.110 Passage of the catheter, followed by air inflation and balloon filling, may allow object removal with gentle catheter traction.

When the emergency physician possesses the appropriate expertise and equipment, or if consultants are available, the next step may be removal with a vacuum device, well suited for some foreign bodies (Figs. 60-15 and 60-16), or forceps; sigmoidoscopy may be a necessary adjunct to such an approach. As with other removal means, the physician should be careful to minimize risk of anorectal perforation. Removal of occult anorectal foreign objects after administration of an enema for symptomatic relief of anal pain was successful in 10% of patients in one series. Experts caution against possible perforation, however, when enemas or cathartics are administered to patients with known rectal foreign bodies, especially foreign bodies with sharp edges.

An assessment of injury to the rectum is indicated after removal of the foreign object. When foreign body retrieval has been simple and the patient does not show increased pain, tenderness, or rectal bleeding, further evaluation for rectal trauma is likely unnecessary. If any of these is present, postremoval sigmoidoscopy may identify small abrasions requiring close follow-up, but in general, hospitalization is necessary only if a rectal laceration or perforation is found. Appropriate antibiotics are indicated in all cases of suspected bowel wall perforation and peritonitis. Long-term follow-up has identified few or no sequelae in patients with rectal foreign bodies.107

Genitourinary Tract

The literature describes a wide variety of genitourinary tract foreign objects, ranging from easily extracted tampons and condoms to penile rings removed only with great difficulty.111,112

History

An accurate history may not be readily obtained because most foreign bodies are placed by the patients themselves. Reports have validated the occasional value of a history, however, as a means to diagnose some genitourinary objects such as those associated with genital body piercing (in patients or sexual partners).113 In children who fear parental disapproval of foreign object placement, secondary signs are the usual presentation. They are brought to medical attention when parents note foul-smelling, purulent discharge or bleeding from the urethra, the vagina, or both.114 Another common presentation in infants is penile constriction caused by inadvertent wrapping of hairs around the shaft, usually just proximal to the corona.115

In older children, rubber bands or string may be placed around the genitalia. In adolescents and adults, metal objects are placed for autoerotic stimulation. Constricting bands may be placed proximal to the scrotum or more often on the penile shaft. These patients frequently have presentations delayed by 12 hours or more. The swelling that renders these constricting bands so difficult to remove also hinders the physical examination, emphasizing the need for an accurate history.115