13 Forehead and temporal recontouring using calcium hydroxylapatite pre-mixed with lidocaine

Summary and Key Features

• Rejuvenation of the upper face should include correction of skin laxity at the temples and placement of volume in the forehead concavity

• Although multiple fillers are available to correct the upper third of the face, we recommend calcium hydroxylapatite for these sites specifically

• Temple correction is best achieved through placement of boluses beginning at the temple and extending to the lateral canthus, followed by massage

• Forehead correction is achieved by placing a bolus of material into the inferior frontal eminence

• Postoperative edema is a common side effect that resolves spontaneously by 72 hours

• Relative ptosis of the eyebrows is also a temporary side effect and is a result of lidocaine and edema, typically resolving within 24 hours

Materials, injection sites, and injection techniques

Materials

CaHA is a filler with relatively high viscosity. Alterations in the viscosity can be implemented without compromising long-term efficacy. Consequently, prior to administration of CaHA into the forehead and temples, the product should be homogeneously mixed with lidocaine. In our clinical practice, the 1.5 mL syringe of CaHA is combined with 0.5 mL of 1% lidocaine for injections in the temple and with 1.0 mL of 1% lidocaine® / normal saline diluent mixture for the forehead. This mixing enhances the ease of massaging product throughout the treated area. An ordinary 3.0 mL syringe containing the diluent can be connected to the 1.5 mL syringe, using a female-to-female Luer lock adapter (Fig. 13.1). Existing research by Busso has shown that 10 passes of the CaHA and the diluent back and forth from syringe to syringe is sufficient for homogeneous distribution of both diluent and dermal filler.

Injection site for the forehead

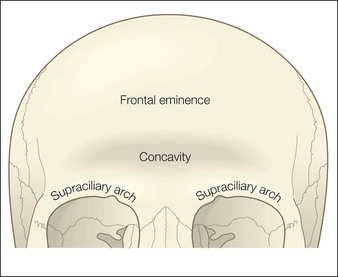

The target in the suprabrow area is the suprabrow concavity. Specifically, this area extends inferiorly to the frontal bone supraciliary ridge and superiorly to the frontal eminence, approximately 3 cm away from the supraciliary arches. Laterally, the space to be injected is marked by extension into the temporal compartment below the temporal cheek fat (Fig. 13.2). The floor of the target injection area is the frontal supraperiosteum and the ceiling is the frontalis muscle.

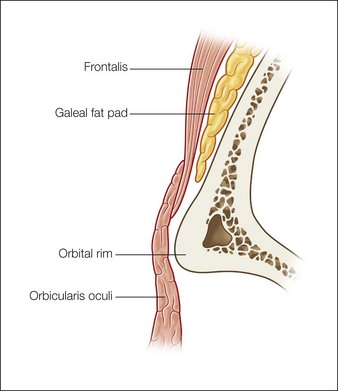

When addressing the medial aspects of the area, injections should extend lateral to the projection of the supraorbital nerve. This projection is located >1 cm from the supraorbital notch or foramen. Injections should be executed at the subcutaneous level, with dermal filler placed at the supraperiosteal level behind the galeal fat pad (Fig. 13.3).

Injection technique for forehead recontouring

A 27-gauge,  -inch (35 mm) needle is used to introduce the CaHA–lidocaine solution into the forehead. A threading bolus is used to place the product in the inferior frontal eminence (Fig. 13.4). The amount of product varies with each patient but the stated objective is reconstitution of the suprabrow arch. When sufficient product has been deposited using retrograde injection for introduction of the bolus, the area is then massaged so that the product is evenly distributed throughout the borders described in the section above. Volumes may range from 1.5 mL to 3.0 mL of CaHA, in addition to the volumes of diluent necessary for mixing.

-inch (35 mm) needle is used to introduce the CaHA–lidocaine solution into the forehead. A threading bolus is used to place the product in the inferior frontal eminence (Fig. 13.4). The amount of product varies with each patient but the stated objective is reconstitution of the suprabrow arch. When sufficient product has been deposited using retrograde injection for introduction of the bolus, the area is then massaged so that the product is evenly distributed throughout the borders described in the section above. Volumes may range from 1.5 mL to 3.0 mL of CaHA, in addition to the volumes of diluent necessary for mixing.

Figure 13.4 A threading bolus is used to place calcium hydroxylapatite in the inferior frontal eminence.

Reproduced from Busso M 2010 Forehead contouring with calcium hydroxylapatite. Dermatologic Surgery 36(S3):1910-1913

Injection technique for temple recontouring

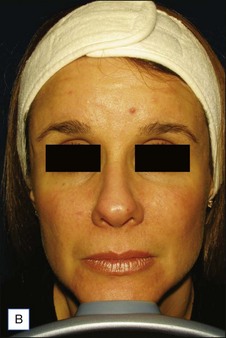

Figures 13.5 and 13.6 are representative results of forehead and temple contouring. In Figure 13.5, a 45-year-old female received 3.0 mL of CaHA mixed with 2.0 mL of 1% lidocaine / normal saline diluent. In Figure 13.6, a 40-year-old female received 1.5 mL of CaHA mixed with 1 mL of 1% lidocaine for her forehead and 3.0 mL of CaHA blended with 1.0 mL of 1% lidocaine in her bilateral temple region.

Busso M. Vectoring approach to midfacial contouring using calcium hydroxylapatite and hyaluronic acid. Cosmetic Dermatology. 2009;22(10):522–528.

Busso M. Forehead contouring with calcium hydroxylapatite. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(S3):1910–1913.

Busso M. Commentary on extrinsic addition of lidocaine to calcium hydroxylapatite. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(11):1795.

Busso M, Voigts R. An investigation of changes in physical properties of injectable calcium hydroxylapatite in a carrier gel when mixed with lidocaine and with lidocaine/epinephrine. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34(1):S16–S24.

Hirmand H. Anatomy and nonsurgical correction of the tear trough deformity. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;125(2):699–708.

Jones D. Semi-permanent and permanent injectable fillers. Dermatologic Clinics. 2009;27(4):433–444.

Knize DM. An anatomically based study of the mechanism of eyebrow ptosis. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1996;97(7):1321–1333.

Knize DM. Anatomic concepts for brow lift procedures. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;124(6):2118–2126.

Le Louarn C, Buthiau D, Buis J. The face recurve concept: medical and surgical applications. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 2007;31(3):219–231. discussion 232

Rohrich RJ, Pessa JE. The fat compartments of the face: anatomy and clinical implications for cosmetic surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2007;119(7):2219–2227.

Sundaram H, Voigts R, Beer K, et al. Comparison of the rheological properties of viscosity and elasticity in two categories of soft tissue fillers: calcium hydroxylapatite and hyaluronic acid. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(S3):1859–1865.

Sykes JM. Applied anatomy of the temporal region and forehead for injectable fillers. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2009;8(10, suppl):S24–S27.

-inch (35 mm), 25-gauge needles attached to 3 mL syringes allows for even injecting and controlled dispersion of the product. It is critical that the patient massage the area post-procedure using the ‘rule of 5s’ – 5 times a day for 5 days for 5 minutes each time.

-inch (35 mm), 25-gauge needles attached to 3 mL syringes allows for even injecting and controlled dispersion of the product. It is critical that the patient massage the area post-procedure using the ‘rule of 5s’ – 5 times a day for 5 days for 5 minutes each time.

-inch (35 mm) needle facilitates placement.

-inch (35 mm) needle facilitates placement. -inch (35 mm) needle can be used to deposit boluses of CaHA plus lidocaine. Depending on the severity of correction, volumes may range from 0.7 mL to as much as 3.0+ mL of CaHA per site. Injections are performed in a retrograde fashion as the needle is withdrawn, to limit inadvertent intravascular injection. After injection, the temples should be massaged vigorously to blend the product into the treated areas, but patients are not required to perform any massage procedures at home.

-inch (35 mm) needle can be used to deposit boluses of CaHA plus lidocaine. Depending on the severity of correction, volumes may range from 0.7 mL to as much as 3.0+ mL of CaHA per site. Injections are performed in a retrograde fashion as the needle is withdrawn, to limit inadvertent intravascular injection. After injection, the temples should be massaged vigorously to blend the product into the treated areas, but patients are not required to perform any massage procedures at home.