CHAPTER SIX FOREARM, WRIST, AND HAND

INTRODUCTION

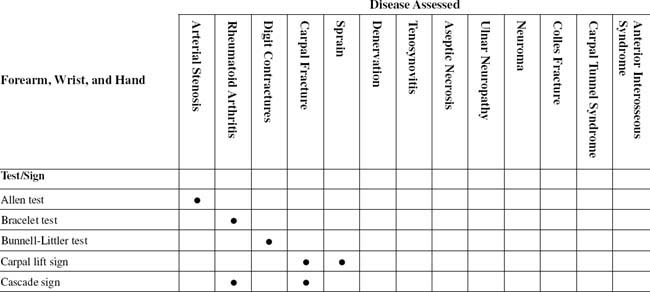

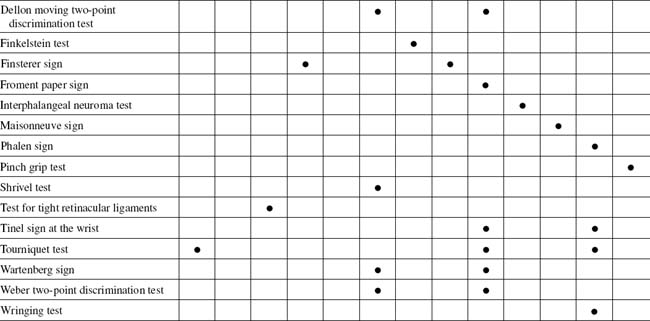

Chronic wrist pain has often been called the lower back pain of hand conditions. Both areas offer the clinician significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. As in the examination of the lower back, a precise evaluation based on thorough knowledge of regional anatomy is essential to successful management (Table 6-1).

The wrist joint is probably the most complicated joint in the body because of its unique arrangement and articulation of the radiocarpal and intercarpal joints. Ligamentous injuries to the carpus can lead to significant and possibly permanent disability. Diagnosis may be difficult with persistent degrees of carpal instability. Definitive treatment modalities have not been perfected. As with most joint injuries, a more thorough understanding of the anatomy and pathogenesis of these injuries is useful (Table 6-2).

TABLE 6-2 PRINCIPAL DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS LIST FOR WRIST PAIN

| Radial side | Tenosynovitis (de Quervain disease) |

|---|---|

| Osteoarthritis of first carpometacarpal joint | |

| Scaphotrapeziotrapezoid osteoarthritis | |

| Scaphoid non-union | |

| Ganglion | |

| Dorsal, central | Kienböck disease |

| Scapholunate dissociation | |

| Scapholunate advanced collapse (SLAC wrist) | |

| Intraosseous ganglion | |

| Ganglion | |

| Ulnar side | Ulnar abutment syndrome |

| Ulnar impaction syndrome | |

| Distal radioulnar joint degenerative arthritis/instability | |

| Ulnar head chondromalacia | |

| Triangular fibrocartilage complex tear | |

| Extensor carpi ulnaris tendonitis/subluxation | |

| Lunotriquetral instability | |

| Pisotriquetral joint disease | |

| Midcarpal instability |

Adapted from Ankarath S: Chronic wrist pain: diagnosis and management, Curr Orthop 20(2):141-151, 2006.

A stable and pain-free wrist is a prerequisite for normal hand function. In contrast, a painful, unstable, or deformed wrist impairs function. The wrist, a common target of rheumatoid arthritis, is adversely affected by the reaction of synovial tissue on capsuloligamentous structures, articular cartilage, and subchondral bone. The mechanical forces of the different muscle groups acting across the wrist also contribute to deformities.

TABLE 6-3 FOREARM, WRIST, AND HAND CROSS-REFERENCE TABLE BY SYNDROME OR TISSUE

| Anterior interosseous syndrome | Pinch grip test |

| Arterial stenosis |

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 6-1 WRIST CARPAL SYSTEM

The nature of injury of the wrist carpal system is determined by:

As with any other orthopedic problem, assessment of wrist and hand disorders begins with a complete history (Box 6-1). Painful disorders of the forearm, wrist, and hand can be classified based on the tissue of origin of pain and its distribution.

ESSENTIAL ANATOMY

The wrist transmits force between the hand and forearm. Force passes through the capitate bone of the distal carpal row, the scaphoid and lunate bones of the proximal carpal row, and onward proximally to the distal end of the radius. These bones are the ones most likely to be fractured or dislocated in injury of the hand-wrist mechanism. Of the two long bones of the forearm, only the radius has true articulation with the carpal bones. The carpal fractures often involve the scaphoid. Scaphoid fractures, with typical tenderness at the anatomic snuffbox, can result in chronic wrist pain because of non-union or collapse of the structure following injury. Wrist radiocarpal trauma can also involve the triangular fibrocartilage complex (Table 6-4).

TABLE 6-4 TRIANGULAR FIBROCARTILAGE COMPLEX INJURY CLASSIFICATION

| Class I: Traumatic |

ESSENTIAL MOTION ASSESSMENT

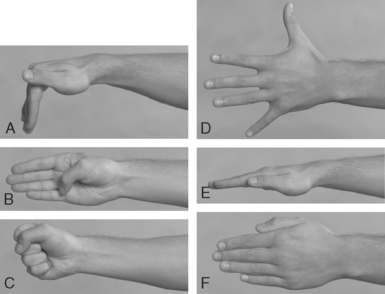

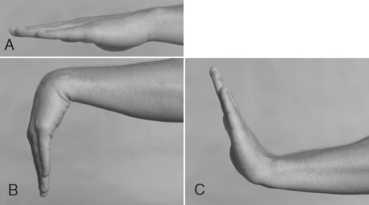

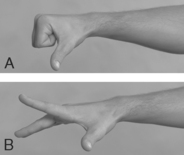

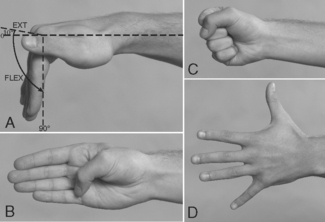

Movements of the wrist comprise flexion, extension, and ulnar and radial deviation. Flexion-extension movements of the fingers occur at both the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and the interphalangeal joints (Fig. 6-1).

Movements of the thumb are described in terms different from those applied to the other digits because the thumb is positioned in a way that is different from the way the fingers are positioned, and the thumb is capable of unique movements not possible in the other digits.

For examination of the wrist-hand range of motion, the middle finger is considered midline (Fig. 6-2). Wrist flexion decreases as the fingers are flexed. Movements of flexion and extension are ultimately limited by muscles and ligaments (Figs. 6-3 and 6-4).

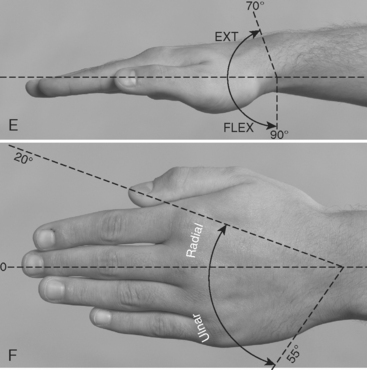

Finger abduction is 20 to 30 degrees at the MCP joints. Finger adduction is 0 degrees at the same joint. The loss of finger abduction or adduction has minimal effect on the activities of daily living. Thumb flexion at the carpometacarpal joint is in a range of 45 to 50 degrees. At the MCP joint, the range is 50 to 55 degrees. At the interphalangeal joint, thumb flexion is in a range of 80 to 90 degrees. Extension of the thumb at the interphalangeal joint is 0 to 5 degrees. Thumb abduction is 60 to 70 degrees. Thumb adduction is 30 degrees. Seventy degrees or less of retained flexion of the thumb at the interphalangeal joint and 50 degrees or less retained flexion at the MCP joint are considered impairments of the thumb in the activities of daily living. Zero degrees of extension at the interphalangeal joint is considered the sole impairment of extension for the thumb. Forty degrees or less of radial abduction and 25 degrees or less of adduction are considered impairments of the thumb in the activities of daily living (Fig. 6-5).

ESSENTIAL MUSCLE FUNCTION ASSESSMENT

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 6-4 MUSCLES OF THE HAND

Muscles controlling movements of the hand are divided into two groups:

FIG. 6-8 Flexion of the interphalangeal joints of the fingers is accomplished by the long flexor tendons.

ESSENTIAL IMAGING

ALLEN TEST

Assessment for Peripheral Vascular Obstruction at the Wrist

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 6-6 REFLEX SYMPATHETIC DYSTROPHY–COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME (RSD-CRPS) LIMB PROTECTION

Three stages of RSD-CRPS limb protection by the patient are:

Comment

Diagnosis of reflex sympathetic dystrophy–complex regional pain syndrome (RSD-CRPS) is initially based on clinical symptoms and signs for the upper extremity, which includes painful disuse of the hand and wrist with a high degree of awareness. Supportive laboratory testing includes positive bone scans, hypervascularity (thermography), and positive sweat test with autonomic dysfunction and quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test. Later, osteoporosis can help confirm the diagnosis. The sympathetic dystrophy scale is effective in confirming and rating the severity of this syndrome (Boxes 6-2 and 6-3).

BOX 6-3 CLASSIFICATION OF COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME (CRPS)—MAJOR CATEGORIES

Adapted from Manning DC: Reflex sympathetic dystrophy, sympathetically maintained pain, and complex regional pain syndrome: diagnoses of inclusion, exclusion, or confusion? J Hand Ther 13(4):260-268, 2000.

PROCEDURE

BRACELET TEST

Assessment for Degenerative Changes of the Wrist Articulations (Rheumatoid Arthritis)

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 6-8 RHEUMATOID DEFORMITY

Rheumatoid Deformity of the Wrist is Usually Characterized by:

BUNNEL-LITTLER TEST

Assessment for Interphalangeal Capsular Contractures

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 6-11 STAGES OF BASAL JOINT THUMB ARTHRITIS BASED ON RADIOLOGICAL APPEARANCE

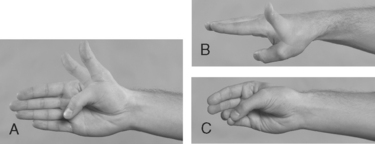

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

DELLON MOVING TWO-POINT DISCRIMINATION TEST

Assessment for Dermatome Sensory Disturbances

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 6-12 TWO-POINT DISCRIMINATION

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

FINSTERER SIGN

Assessment for Lunate Carpal Septic Necrosis

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 6-13 KIENBÖCK DISEASE

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

PINCH GRIP TEST

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

TEST FOR TIGHT RETINACULAR LIGAMENTS

PROCEDURE

TINEL SIGN AT THE WRIST (ALSO KNOWN AS FORMICATION SIGN, DISTAL TINGLING ON PERCUSSION [DTP] SIGN, AND HOFFMAN-TINEL SIGN)

Assessment for Peripheral Neuropathy in Median or Ulnar Nerve Distribution

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 6-18 FIVE PATTERNS OF ULNAR NEUROPATHY DEPENDING ON THE SITE OF THE LESION

PROCEDURE

TOURNIQUET TEST

Assessment for Neural Irritability as a Result of Posterior Interosseous or Median Nerve Compression

Comment

Significant diminution of blood flow to individual digits or to an entire hand results in pale nail beds, slow capillary recovery after skin compression, diminished bleeding after skin puncture, lowering of the skin temperature, and pain of varying intensity. Symptoms and signs of pain, pulselessness, pallor, paresthesia, and paralysis indicate arterial insufficiency or inadequate capillary perfusion (Table 6-5). The coexistence of pallor with cyanosis and rubor is consistent with vasoconstriction and subsequent vasodilation. This sign may occur in the presence of posterior interosseous nerve compression.

TABLE 6-5 BLOND MCINDOE COLD INTOLERANCE SYMPTOM SEVERITY (CISS) QUESTIONNAIRE

| Question | Score |

|---|---|

| 1. Which of the following symptoms of cold intolerance do you experience in your injured limb on exposure to cold? | Not scored |

| Please give each symptom a score between 0 and 10, where 0 = no symptoms at all and 10 = the most severe symptoms imaginable. | |

| Pain, numbness, stiffness, weakness, aching, swelling, skin color change (white/bluish white/blue) | |

| 2. How often do you experience these symptoms? (Please check.) | |

| Continuously, all the time | 10 |

| Several times a day | 8 |

| Once a day | 6 |

| Once a week | 4 |

| Once a month or less | 2 |

| 3. When you develop cold induced symptoms, on your return to a warm environment are the symptoms relieved? (Please check.) | |

| Within a few minutes | 2 |

| Within 30 minutes | 6 |

| After more than 30 minutes | 10 |

| 4. What do you do to ease or prevent your symptoms occurring? (Please check.) | |

| Take no special action | 0 |

| Keep hand in pocket | 2 |

| Wear gloves in cold weather | 4 |

| Wear gloves all the time | 6 |

| Avoid cold weather, stay indoors | 8 |

| Other (please specify) | 10 |

| 5. How much does cold bother your injured hand in the following situations? (Please score 0–10.) | |

| Holding a glass of ice water | 10 |

| Holding a frozen package from the freezer | 10 |

| Washing in cold water | 10 |

| When you get out of a hot bath or shower with air at room temperature | 10 |

| During cold wintry weather | 10 |

| 6. Please state how each of the following activities have been affected as a consequence of cold induced symptoms in your injured hand and score each. (Please score 0–4.) | |

| Domestic chores | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| Hobbies and interests | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| Dressing and undressing | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| Tying your shoelaces | 0 1 2 3 4 |

| Your job | 0 1 2 3 4 |

However, the scores given in question #1 do not count; overall, minimal score of 4 and a maximal score of 100. A score of 30 is the cut-off point for abnormal cold intolerance. Numbness is the most frequent cold-induced symptom, present in 80% of the time. Other symptoms of frequency are stiffness (77%), weakness (72%), aching (67%), pain (63%), skin color change (50%) and swelling (33%).

From Irwin MS et al: Cold intolerance following peripheral nerve injury. Natural history and factors predicting severity of symptoms, J Hand Surg 22B(3):308-316, 1997.

PROCEDURE

WEBER TWO-POINT DISCRIMINATION TEST

Assessment for Diminished Peripheral Nerve Sensibility

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 6-21 QUALITIES OF SENSIBILITY

Five elementary qualities of sensibility evoked by stimulation via:

Comment

Ten zones in the hand are tested, six in the territory of the median nerve and four in the territory of the ulnar nerve. The scores are interpreted as suggested by Imai and colleagues (Table 6-6). A score of 6.10 is interpreted as having no sensation.

| Quality of Sensation (Range 1–5) | Filament Marking |

|---|---|

| 1. Normal | 2.83 |

| 2. Diminished light touch | 3.61 |

| 3. Diminished protective sensation | 4.31 |

| 4. Loss of protective sensation | 4.56 |

| 5. Anesthetic | 6.10 |

From Imai H, Tajima T, Natsuma Y: Interpretation of cutaneous pressure threshold (Semmes-Weinstein monofilament measurement) after median nerve repair and sensory reeducation in the adult, Microsurgery 10(2):142-144, 1989.