CHAPTER 49 Forearm

SKIN AND SOFT TISSUE

SKIN

Cutaneous vascular supply

Fasciocutaneous perforators from the radial artery supply the lateral two-thirds of the anterior surface of the forearm, the lateral (radial) border and the posterior one-quarter of the forearm (except in the distal third) (see Fig. 45.4). These perforators pass in the intermuscular fascia between brachioradialis and flexor carpi radialis and between flexor carpi radialis and flexor digitorum superficialis (see Fig. 49.17). Within the territory of the radial artery is the area of the largest fasciocutaneous perforator, which has recently been named the inferior cubital artery. It extends from the distal apex of the antecubital fossa to midway down the forearm. Fasciocutaneous perforators from the ulnar artery supply an anatomical area which extends from the cubital fossa to the wrist, and from the medial (ulnar) third of the anterior aspect of the forearm around the medial border to the medial one-quarter of the posterior surface of the forearm (see Fig. 49.17, Fig. 45.4).

The distal third of the lateral (radial) aspect of the forearm is supplied by the terminal perforating branches of the anterior interosseous artery (see Fig. 45.4).

The central half of the posterior surface of the forearm, from the lateral edge of extensor digitorum, just below the lateral epicondyle of the humerus, to the wrist, is supplied by fasciocutaneous perforators which arise from the posterior interosseous artery. They reach the skin by passing along the intermuscular fascia between extensor carpi ulnaris and extensor digit minimi (see Fig. 49.17, Fig. 45.4).

For a detailed account of the cutaneous blood supply to the forearm, see Cormack & Lamberty (1994) and the translated works of Salmon (1994).

Cutaneous innervation

The anterior aspect of the forearm is supplied by the anterior branches of the medial and lateral cutaneous nerves of the forearm (see Fig. 45.15). The medial and lateral regions of the posterior aspect of the forearm are supplied by the posterior branches of the medial and lateral cutaneous nerves of the forearm respectively. The central part of the posterior aspect of the forearm is supplied by the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm.

SOFT TISSUE

Interosseous membrane

Oblique cord

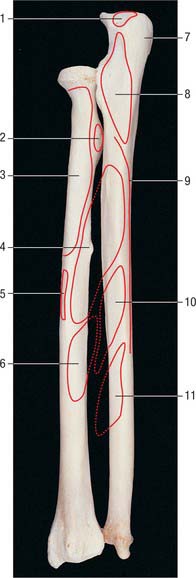

The oblique cord is a small inconstant flat fascial band on the deep head of supinator (Fig. 49.1). It extends from the lateral side of the ulnar tuberosity to the radius a little distal to its tuberosity. Its fibres are at right angles to those in the interosseous membrane. Its functional significance is dubious.

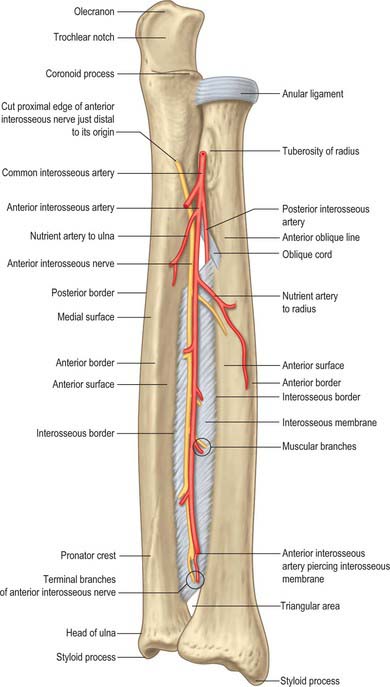

Interosseous membrane

The interosseous membrane is a broad, thin, collagenous sheet (Fig. 49.1). Its fibres slant distomedially between the radial and ulnar interosseous borders, and its distal part is attached to the posterior division of the radial border. Two or three posterior bands occasionally descend distolaterally across the other fibres. The membrane is deficient proximally, starting 2 or 3 cm distal to the radial tuberosity, and broader at midlevel. An oval aperture near its distal margin conducts the anterior interosseous vessels to the back of the forearm, and the posterior interosseous vessels pass through a gap between its proximal border and the oblique cord.

The membrane provides attachments for the deep forearm muscles and connects the radius and ulna. Its fibres appear to transmit forces which act proximally from the hand to the radius, thence to the ulna and humerus. However the hand is usually pronated when subject to these forces, and the membrane is relaxed in complete pronation and supination: the interosseous membrane is only tense when the hand is midway between prone and supine positions. Moreover, the radius can transmit substantial forces directly to the humerus. Anteriorly, in its proximal three-quarters, the membrane is related laterally to flexor pollicis longus and medially to flexor digitorum profundus, and between them to the anterior interosseous vessels and nerve. In its distal quarter it is related to pronator quadratus. Its posterior relations are supinator, abductor pollicis longus, extensors pollicis brevis, longus and indicis and, near the carpus, the anterior interosseous artery and posterior interosseous nerve.

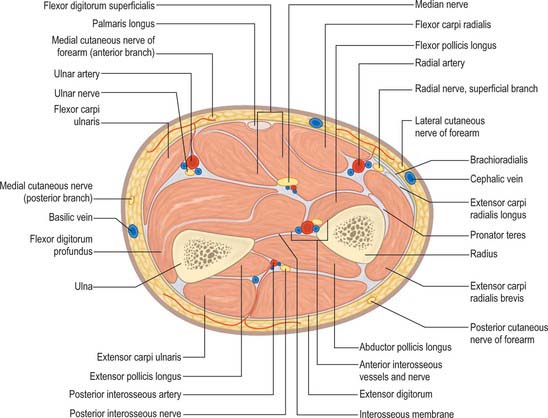

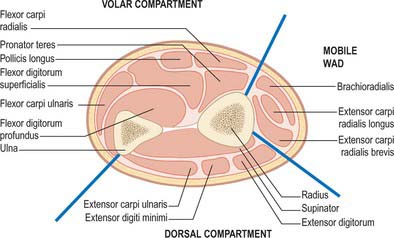

Compartments of the forearm

The antebrachial fascia (deep fascia of the forearm), which is continuous above with the brachial fascia, is a dense general sheath for muscles, collectively and individually, in this region. It is attached to the olecranon and posterior border of the ulna. From its deep surface septa pass between muscles, providing partial attachment for them, and some of these septa reach bone. Muscles also arise from its internal aspect, especially in the upper forearm. This deep fascia, together with the interosseous membrane and fibrous intermuscular septa, divide the forearm into a number of compartments. These are the superficial and deep flexor (anterior) compartments, the extensor (posterior compartment) and a proximolateral compartment known as the mobile wad (encompassing brachioradialis and extensors carpi radialis longus and brevis) (Fig. 49.2). The fascia is much thicker posteriorly and in the lower forearm. It is strengthened above by tendinous fibres from biceps and triceps. Near the wrist, two localized thickenings, the flexor and extensor retinacula, retain the digital tendons in position (p. 879). Vessels and nerves pass through apertures in the fascia. One large aperture anterior to the elbow transmits a venous communication between superficial and deep veins.

BONE

RADIUS

The radius is the lateral bone of the forearm (Fig. 49.3, Fig. 49.4, Fig. 49.5). It has expanded proximal and distal ends; the distal is much the broader. The shaft widens rapidly towards its distal end, is convex laterally and concave anteriorly in its distal part.

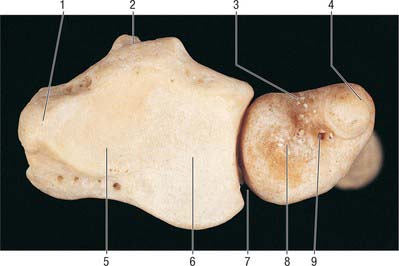

Fig. 49.5 Proximal end of left radius: anterior view. 1. Head. 2. Radial tuberosity. 3. Shaft. 4. Neck.

Shaft

The shaft has a lateral convexity, and is triangular in section (Fig. 49.1). The interosseous border is sharp, except for two areas: proximally, near the tuberosity; and distally, where the interosseous border is the posterior margin of a small, elongated, triangular area, proximal to the ulnar notch. These two areas form the so-called medial surface. The interosseous membrane is attached to its distal three-fourths, and connects the radius to the ulna. The anterior border is obvious at both ends, but rounded and indefinite between them. It descends laterally from the anterolateral part of the tuberosity as the anterior oblique line, which distally becomes a sharp, palpable crest along the lateral margin of the anterior surface. The posterior border is well defined only in its middle third: proximally it ascends medially towards the posteroinferior part of the tuberosity, and distally it is merely a rounded ridge. The anterior surface, between anterior and interosseous borders, is concave transversely and shows a distal forward curvature. Near its midpoint there is a proximally directed nutrient foramen and canal. The posterior surface, between interosseous and posterior borders, is largely flat but may be slightly hollow in the proximal area. The lateral surface is gently convex. Proximally, due to the obliquity of the anterior and posterior borders, it encroaches on the anterior and posterior aspects and is here slightly rough. A finely irregular oval area occurs near the midshaft, and beyond it the surface is smooth.

Distal end

The distal end of the radius (Fig. 49.6) is the widest part. It is four-sided in section. The lateral surface is slightly rough, projecting distally as a styloid process which is palpable when tendons around it are slack. The smooth carpal articular surface is divided by a ridge into medial and lateral areas. The medial is quadrangular, whereas the lateral is triangular and curves on to the styloid process. The anterior surface is a thick, prominent ridge, palpable even through overlying tendons, 2 cm proximal to the thenar eminence. The medial surface is the ulnar notch, which is smooth and anteroposteriorly concave for articulation with the head of the ulna. The posterior surface displays a palpable dorsal tubercle (Lister’s tubercle), which is limited medially by an oblique groove and is in line with the cleft between the index and middle fingers. Lateral to the tubercle there is a wide, shallow groove, divided by a faint vertical ridge.

Muscle, ligament and articular attachments

The proximal two-thirds of the anterior surface provides an extensive area for attachment of flexor pollicis longus, which conceals the nutrient foramen. Pronator quadratus is attached to the distal quarter, and pronator teres is attached to a rough area near the midpoint of its lateral surface, at its maximal curvature. Proximally, the lateral surface widens into a long V-shaped area for supinator (Fig. 49.3, Fig. 49.4). Distal to pronator teres, the lateral surface is covered by tendons of the radial extensors. On the posterior surface, abductor pollicis longus is attached proximally and, more distally, extensor pollicis brevis. The remaining surface is devoid of attachments and covered by the long and short extensors of the thumb.

The radial styloid process projects beyond that of the ulna, its apex concealed by the tendons of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis. The lateral radiocarpal ligament is attached to its tip. The lateral surface, near the styloid process, receives the attachment of brachioradialis and is crossed obliquely, downwards and forwards, by the tendons of abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis. The terminal ridge on the anterior surface of the lower end is an attachment for the palmar radiocarpal ligament. The base of the triangular articular disc of the inferior radio-ulnar joint is attached to a smooth ridge distal to the ulnar notch. From the latter, a narrow protrusion of synovial membrane extends proximally anterior to the lower end of the interosseous membrane (p. 839). The lateral part of the carpal articular surface articulates with the scaphoid, and the medial part with the lateral part of the lunate. In full adduction, the proximal surface of the lunate is wholly in contact with the radius.

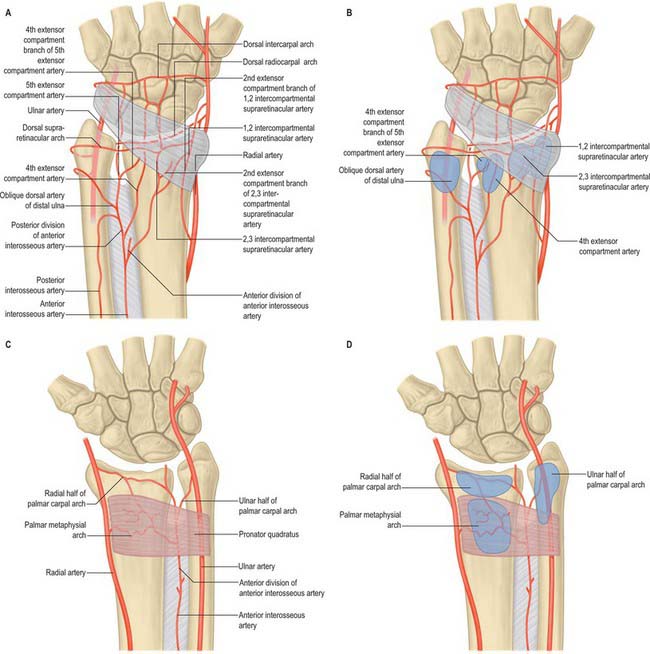

Vascular supply

The dorsal metaphysial supply of the distal radius is of particular importance to reconstructive hand surgeons because of its potential use in raising vascularized pedicled bone grafts (Fig. 49.7). Consistent branches connecting the anterior interosseous artery proximally to the dorsal carpal arch distally pass through the fourth and fifth extensor compartments of the wrist and provide metaphysial nutrient arteries. Intercompartmental vessels send nutrient arteries to the radius through the retinaculum between the first and second dorsal compartments, and the second and third dorsal compartments. These vessels originate from the radial artery and anterior interosseous arteries respectively, and anastomose with the dorsal carpal arch. For an anatomical description detailing the practical application of such pedicled bone grafts see Sheetz et al (1995).

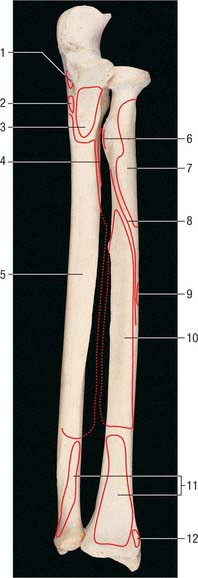

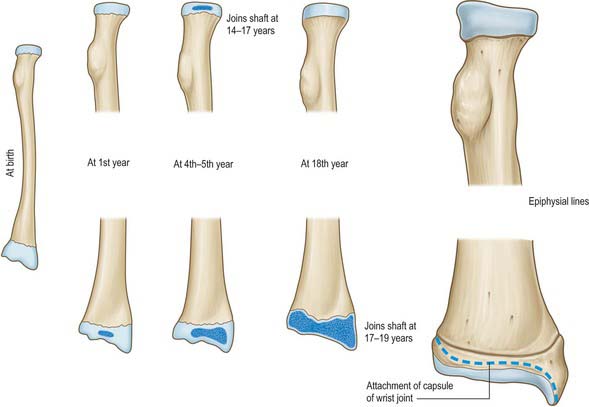

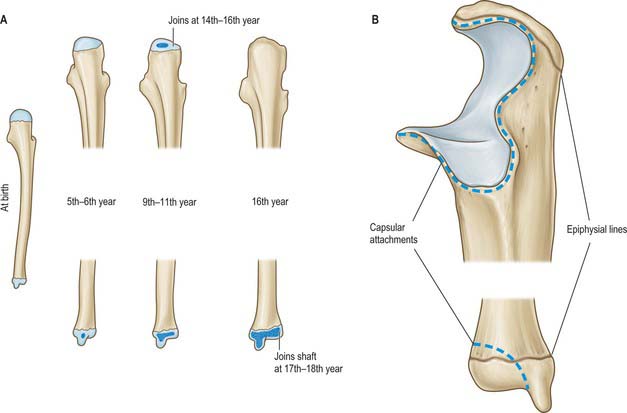

Ossification

The radius ossifies from three centres. One appears centrally in the shaft in the eighth week of fetal life, and the others appear in each end (Fig. 49.8, Fig. 49.9). Ossification begins in the distal epiphysis towards the end of the first postnatal year, and in the proximal epiphysis during the fourth year in females, and fifth in males. The proximal epiphysis fuses in the 14th year in females, 17th in males, and the distal in the 17th and 19th years respectively. A fourth centre sometimes appears in the tuberosity at about the 14th or 15th year.

ULNA

The ulna is medial to the radius in the supinated forearm (Fig. 49.3, Fig. 49.4). Its proximal end is a massive hook which is concave forwards (Fig. 49.10). The lateral border of the shaft is a sharp interosseous crest. The bone diminishes progressively from its proximal mass throughout almost its whole length, but at its distal end expands into a small rounded head and styloid process. The shaft is triangular in section but has no appreciable double curve. In its whole length it is slightly convex posteriorly. Mediolaterally, its profile is sinuous. The proximal half has a slight laterally concave curvature, and the distal half a medially concave curvature.

Proximal end

The proximal end has large olecranon and coronoid processes and trochlear and radial notches which articulate with the humerus and radius (Fig. 49.10). The olecranon is more proximal and is bent forwards at its summit like a beak, which enters the humeral olecranon fossa in extension. Its posterior surface is smooth, triangular and subcutaneous, and its proximal border underlies the ‘point’ of the elbow. In extension it can be felt near a line joining the humeral epicondyles, but in flexion it descends, so that the three osseous points form an isosceles triangle. Its anterior, articular surface forms the proximal area of the trochlear notch. Its base is slightly constricted where it joins the shaft and is the narrowest part of the proximal ulna. The coronoid process projects anteriorly distal to the olecranon. Its proximal aspect forms the distal part of the trochlear notch. On the lateral surface, distal to the trochlear notch, there is a shallow, smooth, oval radial notch which articulates with the radial head. Distal to the radial notch the surface is hollow to accommodate the radial tuberosity during pronation and supination. The anterior surface of the coronoid is triangular. Its distal part is the tuberosity of the ulna. Its medial border is sharp and bears a small tubercle proximally.

The trochlear notch articulates with the trochlea of the humerus. It is constricted at the junction of the olecranon and coronoid processes, where their articular surfaces may be separated by a narrow rough non-articular strip. A smooth ridge, adapted to the groove on the humeral trochlea, divides the notch into medial and lateral parts. The medial fits into the trochlear flange. The radial notch, an oval or oblong proximal depression on the lateral aspect of the coronoid process, articulates with the periphery of the radial head, and is separated from the trochlear notch by a smooth ridge (Fig. 49.10).

Shaft

The shaft is triangular in section in its proximal three-fourths, but distally is almost cylindrical (Fig. 49.3, Fig. 49.4). It has anterior, posterior and medial surfaces and interosseous, posterior and anterior borders. The interosseous border is a conspicuous lateral crest in its middle two-fourths. Proximally it becomes the supinator crest, which is continuous with the posterior border of a depression distal to the radial notch. Distally, it disappears. The rounded anterior border starts medial to the ulnar tuberosity, descends backwards, and is usually traceable to the base of the styloid process. The posterior border, also rounded, descends from the apex of the posterior aspect of the olecranon, and curves laterally to reach the styloid process. It is palpable throughout its length in a longitudinal furrow which is most obvious when the elbow is fully flexed.

The anterior surface, between the interosseous and anterior borders, is longitudinally grooved, sometimes deeply (Fig. 49.3). Proximal to its midpoint there is a nutrient foramen, which is directed proximally and contains a branch of the anterior interosseous artery. Distally, it is crossed obliquely by a rough, variable prominence, descending from the interosseous to the anterior border. The medial surface, between the anterior and posterior borders, is transversely convex and smooth. The posterior surface, between the posterior and interosseous borders, is divided into three areas (Fig. 49.4). The most proximal is limited by a sometimes faint oblique line ascending laterally from the junction of the middle and upper thirds of the posterior border to the posterior end of the radial notch. The region distal to this line is divided into a larger medial and narrower lateral strip by a vertical ridge, usually distinct only in its proximal three-fourths.

Distal end

The distal end is slightly expanded and has a head and styloid process. The head is visible in pronation on the posteromedial carpal aspect, and can be gripped when the supinated hand is flexed. Its lateral convex articular surface fits the radial ulnar notch. Its smooth distal surface (Fig. 49.6) is separated from the carpus by an articular disc, the apex of which is attached to a rough area between the articular surface and styloid process. The latter, a short, round, posterolateral projection of the distal end of the ulna, is palpable (most readily in supination) about 1 cm proximal to the plane of the radial styloid. A posterior vertical groove is present between the head and styloid process.

Vascular supply

Multiple metaphysial nutrient foramina transmit branches of the radial, ulnar, anterior and posterior interosseous arteries (Fig. 49.7). These vessels give off a number of smaller segmental branches. Usually one, but occasionally two, major nutrient diaphysial foramina are located on the anterior surface of the bone, directed proximally toward the elbow. A network of small fascioperiosteal and musculoperiosteal branches given off from the compartmental vessels reaches the bone via septal and muscular attachments.

Ossification

The ulna ossifies from four main centres, one each in the shaft and distal end and two in the olecranon (Fig. 49.11). Ossification begins in the midshaft about the eighth fetal week, and extends rapidly. In the fifth (females) and sixth (males) years, a centre appears in the distal end, and extends into the styloid process. The distal olecranon is ossified as an extension from the shaft, the remainder from two centres, one for the proximal trochlear surface, and the other for a thin scale-like proximal epiphysis on its summit. The latter appears in the ninth year in females, 11th in males. The whole proximal epiphysis has joined the shaft by the 14th year in females, sixteenth in males. The distal epiphysis unites with the shaft in the 17th year in females, 18th in males.

MUSCLES

ANTERIOR COMPARTMENT

The anterior compartment contains the flexor muscles of the forearm which are arranged in superficial and deep groups. Chronic tendonitis of the common flexor tendon origin produces medial epicondylitis of the elbow, leading to pain and tenderness. It is a frequent complaint among golfers. A detailed account of the architectural properties of the muscles of the arm and forearm is given by Leiber et al (1992).

Superficial flexor compartment

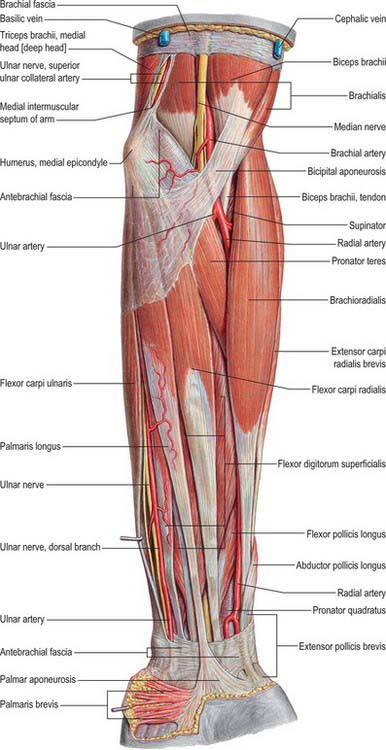

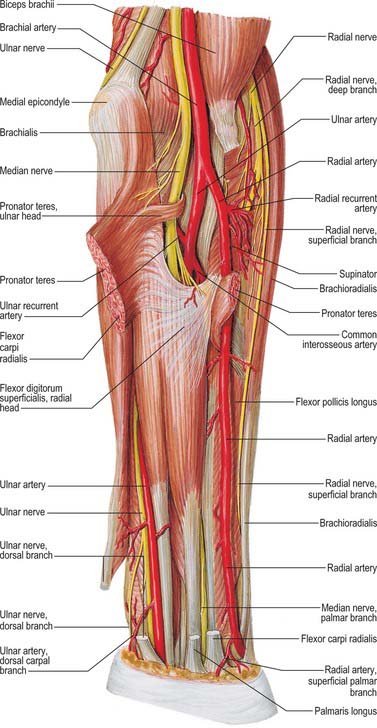

Muscles of the superficial flexor compartment arise from the medial epicondyle of the humerus by a common tendon. They are pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor carpi ulnaris (Fig. 49.12). They have additional attachments to the antebrachial fascia near the elbow and to the septa that pass from this fascia between individual muscles.

Pronator teres

Pronator teres has humeral and ulna attachments (Fig. 49.3, Fig. 49.12, Fig. 49.13). The humeral head, the larger and more superficial of the two, arises just proximal to the medial epicondyle, from the common tendon of origin of the flexor muscles, from the intermuscular septum between it and flexor carpi radialis, and from antebrachial fascia. The smaller ulnar head springs from the medial side of the coronoid process of the ulna, distal to the attachment of flexor digitorum superficialis, and joins the humeral head at an acute angle. The muscle passes obliquely across the forearm to end in a flat tendon that is attached to a rough area midway along the lateral surface of the radial shaft at the ‘summit’ of its lateral curve. The coronoid attachment may be absent. Accessory slips may arise from a supracondylar process of the humerus, if it is present, or from biceps, brachialis or the medial intermuscular septum.

Flexor carpi radialis

Flexor carpi radialis lies medial to pronator teres, and arises from the medial epicondyle via the common flexor tendon, from the antebrachial fascia and from adjacent intermuscular septa (Fig. 49.12). Its fusiform belly ends, rather more than halfway to the wrist, in a long tendon which passes within a synovial sheath through a lateral canal, formed by the flexor retinaculum above and a groove on the trapezium beneath. It inserts on the palmar surface of the base of the second metacarpal, sending a slip to the third metacarpal. These distal attachments are hidden by the oblique head of adductor pollicis. The muscle rarely may be absent. It may have accessory slips from the biceps tendon, bicipital aponeurosis, coronoid process or radius. Distally it may also be attached to the flexor retinaculum, trapezium or fourth metacarpal.

Flexor digitorum superficialis

Flexor digitorum superficialis (sublimis) lies deep to the preceding muscles (Fig. 49.12). It is the largest of the superficial flexors, and arises by two heads. The humero-ulnar head arises from the medial epicondyle of the humerus via the common tendon; the anterior band of the ulnar collateral ligament; adjacent intermuscular septa, and from the medial side of the coronoid process proximal to the ulnar origin of pronator teres. The radial head, a thin sheet of muscle, arises from the anterior radial border extending from the radial tuberosity to the insertion of pronator teres. The median nerve and ulnar artery descend between the heads. The muscle usually separates into two strata, directed to digits 2–5. The superficial stratum, joined laterally by the radial head, divides into two tendons for the middle and ring finger. The deep stratum gives off a muscular slip to join the superficial fibres directed to the ring finger, and then ends in two tendons for the index and little finger. As the tendons pass behind the flexor retinaculum they are arranged in pairs: the superficial pair pass to the middle and ring fingers, the deep to the index and little finger. Distal to the carpal tunnel the four tendons diverge. Each passes towards a finger superficial to the corresponding flexor digitorum profundus tendon. The two tendons for each finger enter the digital flexor sheath (which starts over the metacarpophalangeal joint) in this relationship. The superficialis tendon then splits into two bundles which pass around the profundus to lie posteriorly. They subsequently reunite and insert into the anterior surface of the middle phalanx. Some fibres interchange from one bundle to another.

Palmaris longus

Palmaris longus is a slender, fusiform muscle medial to flexor carpi radialis (Fig. 49.12). It springs from the medial epicondyle by the common tendon, and from adjacent intermuscular septa and deep fascia. It converges on a long tendon, which passes anterior (superficial) to the flexor retinaculum. A few fibres leave the tendon and interweave with the transverse fibres of the retinaculum, but most of the tendon passes distally. As the tendon crosses the retinaculum it broadens out to become a flat sheet which becomes incorporated into the palmar aponeurosis. Palmaris longus is often absent on one or both sides.

Flexor carpi ulnaris

Flexor carpi ulnaris is the most medial of the superficial forearm flexors (Fig. 49.12). It arises by two heads, humeral and ulnar, connected by a tendinous arch. The small humeral head arises from the medial epicondyle via the common tendon. The ulnar head has an extensive origin from the medial margin of the olecranon and proximal two-thirds of the posterior border of the ulna, an aponeurosis (which it shares with extensor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus), and from the intermuscular septum between it and flexor digitorum superficialis. Occasionally there is a slip from the coronoid process. A thick tendon forms along its anterolateral border in its distal half. The tendon is attached to the pisiform, and thence prolonged to the hamate and fifth metacarpal by pisohamate and pisometacarpal ligaments. The attachment to the flexor retinaculum and the fourth or fifth metacarpal bones is sometimes substantial.

Deep flexor compartment

Flexor digitorum profundus

Flexor digitorum profundus arises deep to the superficial flexors from about the upper three-quarters of the anterior and medial surfaces of the ulna (Fig. 49.13, see Fig. 49.19). It embraces the attachment of brachialis above and extends distally almost to pronator quadratus. It also arises from a depression on the medial side of the coronoid process, the upper three-quarters of the posterior ulnar border (by an aponeurosis which it shares with flexor and extensor carpi ulnaris), and the anterior surface of the ulnar half of the interosseous membrane. The muscle ends in four tendons, which run initially posterior (deep) to the tendons of flexor digitorum superficialis and the flexor retinaculum. The part of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle which acts on the index finger is usually distinct throughout. The tendons for the other fingers are interconnected by areolar tissue and tendinous slips as far as the palm. Anterior to their proximal phalanges, the tendons pass through the tendons of flexor digitorum superficialis to insert on the palmar surfaces of the bases of the distal phalanges. The tendons of the profundus undergo fascicular rearrangement as they pass through those of superficialis.

Flexor digitorum profundus is capable of flexing any or all of the joints over which it passes. It therefore has a role in coordinated finger flexion, but it is the only muscle capable of flexing the distal interphalangeal joints. The index finger tendon is usually capable of independent function, whereas the other three work together. Electromyographically flexor digitorum profundus acts alone in gentle digital flexion and is reinforced by superficialis for greater force and/or velocity.

Flexor pollicis longus

Flexor pollicis longus is lateral to flexor digitorum profundus (Fig. 49.13). It arises from the grooved anterior surface of the radius, and extends from below its tuberosity to the upper attachment of pronator quadratus. It also arises from the adjacent interosseous membrane, and frequently by a variable slip from the lateral, or more rarely medial, border of the coronoid process, or from the medial epicondyle of the humerus. The muscle ends in a flattened tendon, which passes behind the flexor retinaculum, between opponens pollicis and the oblique head of adductor pollicis, to enter a synovial sheath. It inserts on the palmar surface of the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb.

Pronator quadratus

Pronator quadratus is a flat, quadrilateral muscle which extends across the front of the distal parts of the radius and ulna (Fig. 49.13, see Fig. 49.19). It arises from the oblique ridge on the anterior surface of the shaft of the ulna, the medial part of this surface, and a strong aponeurosis which covers the medial third of the muscle. The fibres pass laterally and slightly downwards to the distal quarter of the anterior border and surface of the shaft of the radius. Deeper fibres insert into the triangular area above the ulnar notch of the radius.

POSTERIOR COMPARTMENT

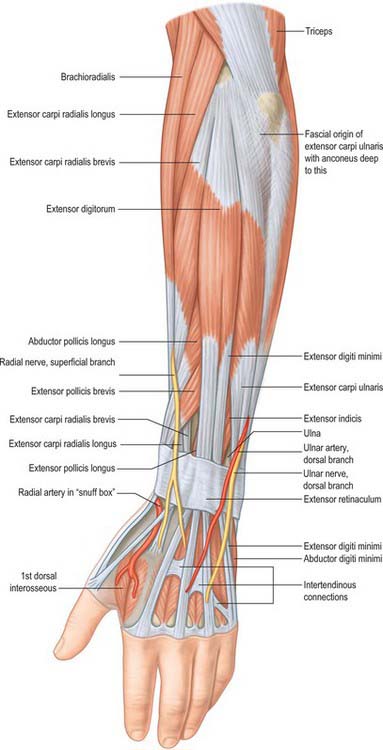

Superficial extensor compartment

Brachioradialis

Brachioradialis is the most superficial muscle along the radial side of the forearm, and forms the lateral border of the cubital fossa (Fig. 49.14). It arises from the proximal two-thirds of the lateral supracondylar ridge of the humerus and the anterior surface of the lateral intermuscular septum. The muscle fibres end above mid-forearm level in a flat tendon which inserts on the lateral side of the distal end of the radius, usually just proximal to its styloid process. Occasionally this attachment may be much more proximal.

Extensor carpi radialis brevis

Extensor carpi radialis brevis is shorter than extensor carpi radialis longus and is covered by it (Fig. 49.14). The tendon passes deep to abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis, then under the extensor retinaculum, where it lies in a shallow groove on the back of the radius, medial to the tendon of extensor carpi radialis longus, and separated from it by a low ridge. These two tendons share a common synovial sheath.

Extensor digitorum

Extensor digitorum arises from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus via the common extensor tendon, the adjacent intermuscular septa and the antebrachial fascia (Fig. 49.14). It divides distally into four tendons, which pass, in a common synovial sheath with the tendon of extensor indicis, through a tunnel under the extensor retinaculum. The tendons diverge on the dorsum of the hand, one to each finger. The tendon to the index finger is accompanied by extensor indicis, which lies ulnar (medial) to it. On the dorsum of the hand, adjacent tendons are linked by three variable intertendinous connections (juncturae tendinae), which are inclined distally and radially. The digital attachments enter a fibrous expansion on the dorsum of the proximal phalanges to which lumbrical, interosseous and digital extensor tendons all contribute.

Extensor digiti minimi

Extensor digiti minimi is a slender muscle medial to, and usually connected with, extensor digitorum (Fig. 49.14). It arises from the common extensor tendon by a thin tendinous slip and adjacent intermuscular septa. It frequently has an additional origin from the antebrachial fascia. Its long tendon slides in a separate compartment of the extensor retinaculum just behind the inferior radio-ulnar joint. Distal to the retinaculum, the tendon typically splits into two, and the lateral slip is joined by a tendon from extensor digitorum. All three tendons are attached to the dorsal digital expansion of the fifth digit, and there may be a slip to the fourth digit.

Extensor digiti minimi is rarely absent, but sometimes it is fused with extensor digitorum.

Extensor carpi ulnaris

Extensor carpi ulnaris arises from the lateral epicondyle via the common extensor tendon, the posterior border of the ulna (by an aponeurosis shared with flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus), and overlying fascia (Fig. 49.14). It ends in a tendon that slides in a groove between the head and the styloid process of the ulna, in a separate compartment of the extensor retinaculum, and is ultimately attached to a tubercle on the medial side of the fifth metacarpal base.

Anconeus

Anconeus is a small, triangular muscle posterior to the elbow joint and is partially blended with triceps (Fig. 49.14). Anconeus arises by a separate tendon from the posterior surface of the lateral epicondyle of the humerus. Its fibres diverge medially towards the ulna, covering the posterior aspect of the annular ligament, and are attached to the lateral aspect of the olecranon and proximal quarter of the posterior surface of the shaft of the ulna.

The extent to which anconeus fuses with triceps or extensor carpi ulnaris is variable.

Deep extensor compartment

The five deep forearm extensor muscles are abductor pollicis longus, extensor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis (which all act on the thumb), extensor indicis and supinator (Fig. 49.15). Apart from supinator, all are attached proximally only to the forearm bones.

Abductor pollicis longus

Abductor pollicis longus arises from the posterior surface of the shaft of the ulna distal to anconeus, the adjoining interosseous membrane, and the middle third of the posterior surface of the radius distal to the attachment of supinator (Fig. 49.15). It descends laterally, becoming superficial in the distal forearm, where it is visible as an oblique elevation (Fig. 49.14). The muscle fibres end in a tendon just proximal to the wrist. The tendon runs in a groove on the lateral side of the distal end of the radius accompanied by the tendon of extensor pollicis brevis. It usually splits into two slips, one of which is attached to the radial side of the first metacarpal base, and the other is attached to the trapezium. Slips from the tendon may continue into opponens pollicis or abductor pollicis brevis. Occasionally the muscle itself may be wholly or partially divided.

Extensor pollicis longus

Extensor pollicis longus is larger than extensor pollicis brevis, whose proximal attachment it partly covers (Fig. 49.14, Fig. 49.15). It arises from the lateral part of the middle third of the posterior surface of the shaft of the ulna below abductor pollicis longus, and the adjacent interosseous membrane. The tendon passes through a separate compartment of the extensor retinaculum in a narrow, oblique groove on the back of the distal end of the radius. It turns around a bony fulcrum, Lister’s tubercle, which changes its line of pull from that of the forearm to that of the thumb, and is attached to the base of the distal phalanx of the thumb. The sides of the tendon are joined on the dorsum of the proximal phalanx by expansions from the tendon of abductor pollicis brevis laterally, and from the first palmar interosseous and adductor pollicis medially.

After passing around Lister’s tubercle, the tendon of extensor pollicis longus crosses the tendons of extensor carpi radialis brevis and longus obliquely (Fig. 49.14). When the thumb is fully extended the tendon is separated from extensor pollicis brevis by a triangular depression or fossa, the so-called ‘anatomical snuff-box’. Bony structures can be felt in the floor of this fossa by deep palpation. In proximal to distal order they are the radial styloid, the smooth convex articular surface of the scaphoid, the trapezium, and the base of the first metacarpal. The latter are more easily felt during metacarpal movement, while the scaphoid is more easily felt during adduction and abduction of the hand.

Extensor pollicis brevis

Extensor pollicis brevis arises from the posterior surface of the radius distal to abductor pollicis longus, and from the adjacent interosseous membrane (Fig. 49.14, Fig. 49.15). The tendon is inserted into the base of the proximal phalanx of the thumb, and commonly has an additional attachment to the base of the distal phalanx, usually through a fasciculus which joins the tendon of extensor pollicis longus. Extensor pollicis brevis may be absent or fused completely with abductor pollicis longus.

Extensor pollicis brevis is ulnar (medial) to, and closely connected with, abductor pollicis longus (Fig. 49.14, Fig. 49.15). In the distal forearm, the two muscles emerge between extensor carpi radialis brevis and extensor digitorum, and pass obliquely across the tendons of the radial extensors of the wrist. They cover the distal part of brachioradialis, and pass through the most lateral compartment of the extensor retinaculum in a single synovial sheath, sharing a groove in the distal radius. Ultimately they cross, superficial to the radial styloid process and radial artery, to reach the dorsolateral base of the proximal phalanx of the thumb.

Extensor indicis

Extensor indicis is a narrow, elongated muscle which lies medial and parallel to extensor pollicis longus (Fig. 49.15). It arises from the posterior surface of the ulna distal to extensor pollicis longus, and the adjacent interosseous membrane. Its tendon passes under the extensor retinaculum in a common compartment with the tendons of extensor digitorum. Opposite the head of the second metacarpal it joins the ulnar side of the tendon of extensor digitorum which serves the index finger.

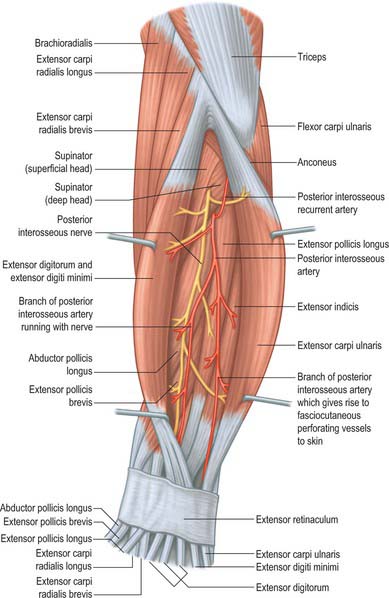

Supinator

Supinator surrounds the proximal third of the radius and has superficial and deep layers (Fig. 49.15). The two parts arise together, the superficial by tendinous, and the deep by muscular fibres, from the lateral epicondyle of the humerus; the radial collateral ligament of the elbow joint and the anular ligament of the superior radio-ulnar joint; the supinator crest of the ulna and the posterior part of the triangular depression in front of it; and an aponeurosis which covers the muscle. Supinator is attached distally to the lateral surface of the proximal third of the radius, down to the insertion of pronator teres. The radial attachment extends on to the anterior and posterior surfaces between the anterior oblique line and the fainter posterior oblique ‘ridge’ (Fig. 49.4).

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

ARTERIES

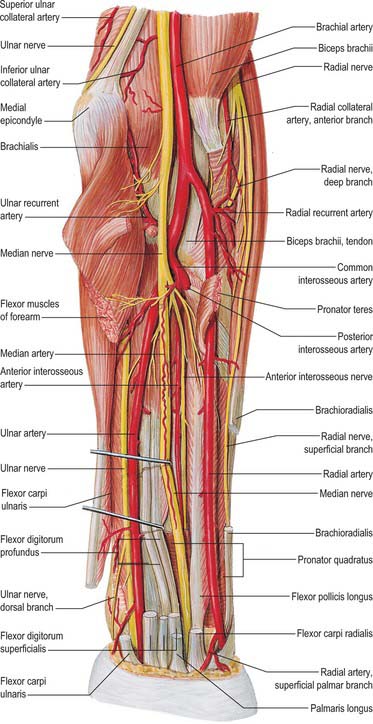

Radial artery

The radial artery is smaller than the ulnar artery, yet appears a more direct continuation of the brachial artery (Fig. 49.12, Fig. 49.13, see Fig. 49.19). It normally starts 1 cm distal to the flexion crease of the elbow. It descends along the lateral side of the forearm, accompanied by paired venae comitantes, from the medial side of the neck of the radius to the wrist, where it is palpable between flexor carpi radialis medially and the salient anterior border of the radius. The artery is medial to the radial shaft proximally, and anterior to it distally. Proximally it is overlapped anteriorly by the belly of brachioradialis, but elsewhere in its course it is covered only by the skin, and superficial and deep fasciae. Its posterior relations in the forearm are successively the tendon of biceps, supinator, the distal attachment of pronator teres, the radial head of flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor pollicis longus, pronator quadratus and the lower end of the radius (where its pulsation is most accessible). Brachioradialis is lateral to the artery throughout its length. Pronator teres is medial to the proximal part of the artery and the tendon of flexor carpi radialis is medial to the distal portion. The superficial radial nerve lies lateral to the middle third of the radial artery: multiple branches from the artery supply the nerve throughout its length.

The course and distribution of the radial artery in the wrist and hand are described on page 890.

Ulnar artery

The ulnar artery is the larger terminal branch of the brachial artery (Fig. 49.12, Fig. 49.13, see Fig. 49.19). It starts 1 cm distal to the flexion crease of the elbow and reaches the medial side of the forearm midway between elbow and wrist. In the forearm the artery initially lies on brachialis and deep to pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, palmaris longus and flexor digitorum superficialis. It subsequently lies on flexor digitorum profundus, between flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum superficialis, and is covered by the skin, superficial and deep fasciae. The median nerve is a medial relation for approximately 2.5 cm distal to the elbow, and then crosses the artery, from which it is separated by the ulnar head of pronator teres. The ulnar nerve lies medial to the distal two-thirds of the artery, which supplies the nerve throughout its length. The palmar cutaneous branch of the ulnar nerve descends along the ulnar artery to reach the hand. The ulnar artery crosses the flexor retinaculum lateral to the ulnar nerve and pisiform bone to enter the hand.

The ulnar artery is accompanied throughout its length by venae comitantes.

The course and distribution of the ulnar artery in the wrist and hand are described on page 893.

Branches in the forearm

Anterior and posterior ulnar recurrent arteries

The anterior and posterior ulnar recurrent arteries are described on page 835.

The common interosseous artery is a short branch of the ulnar artery (Fig. 49.13, see Fig. 49.19). It arises just distal to the radial tuberosity and passes back to the proximal border of the interosseous membrane, where it divides into the anterior and posterior interosseous arteries. Occasionally, the common interosseous artery is a branch of the radial artery.

The anterior interosseous artery descends on the anterior aspect of the interosseous membrane with the anterior interosseous branch of the median nerve (see Fig. 49.19). It is overlapped by contiguous sides of flexor digitorum profundus and flexor pollicis longus. Shortly after its origin, it usually gives off a slender median artery. This accompanies and supplies the median nerve as far as the palm, where it may join the superficial palmar arch or end as one or two palmar digital arteries. (The median artery can also arise from the ulnar or the common interosseous artery.)

The posterior interosseous artery is usually smaller than the anterior (Fig. 49.15, Fig. 49.17, Fig. 49.18). It passes dorsally between the oblique cord and proximal border of the interosseous membrane and then between supinator and abductor pollicis longus. It descends deep in the groove between extensor carpi ulnaris and the extensor digiti minimi part of extensor digitorum. While in the groove it gives rise to multiple muscular branches which supply these muscles and fasciocutaneous perforators which travel in the intermuscular septum between extensor carpi ulnaris and extensor digiti minimi. These fasciocutaneous vessels provide the anatomical basis for raising a dorsal forearm skin flap, which is usually pedicled, based on the posterior interosseous artery and its venae comitantes. Known as the posterior interosseous artery flap, it is used for reconstructing areas of missing tissue in the forearm and proximal part of the hand.

VEINS

Superficial veins

Cephalic vein

The cephalic vein (see Fig. 45.5) usually forms over the ‘anatomical snuff-box’ from the radial end of the dorsal venous plexus. It curves proximally around the radial side of the forearm to gain its ventral aspect, and receives veins from both aspects of the forearm. Distal to the elbow a branch, the median cubital vein, diverges proximomedially to reach the basilic vein. The median cubital vein is joined by a branch from the deep veins.

The further course of the cephalic vein is described in the arm on page 828.

Basilic vein

The basilic vein starts medially in the dorsal venous network of the hand (Fig. 45.5). It ascends posteromedially in the forearm, inclining forwards to the anterior surface distal to the elbow, where it is joined by the median cubital vein. It then ascends superficial to and between biceps and pronator teres, and is crossed by filaments of the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm which pass both superficial and deep to the vein.

The course of the basilic vein in the arm is described on page 828.

INNERVATION

Median nerve

The median nerve usually enters the forearm between the heads of pronator teres (Fig. 49.12, Fig. 49.13, Fig. 49.16, Fig. 49.17, Fig. 49.18). (Occasionally the nerve passes posterior to both heads of pronator teres, or it may pass through the humeral head). It crosses to the lateral side of the ulnar artery, from which it is separated by the deep head of pronator teres. It passes behind a tendinous bridge between the humero-ulnar and radial heads of the flexor digitorum superficialis, and descends through the forearm posterior and adherent to flexor digitorum superficialis and anterior to flexor digitorum profundus. About 5 cm proximal to the flexor retinaculum it emerges from behind the lateral edge of flexor digitorum superficialis, and becomes superficial just proximal to the wrist. Here it lies between the tendons of flexor digitorum superficialis and flexor carpi radialis, projecting laterally from beneath the tendon of palmaris longus (Fig. 49.13, Fig. 49.19). It then passes deep to the flexor retinaculum into the palm. In the forearm the median nerve is accompanied by the median branch of the anterior interosseous artery.

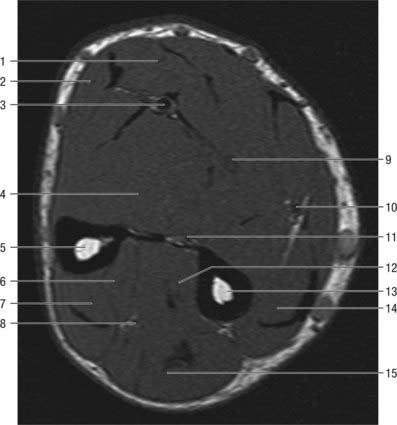

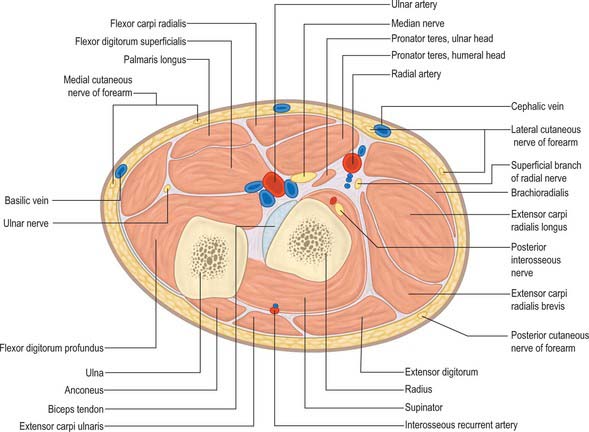

Fig. 49.16 Transverse section through the left forearm at the level of the radial tuberosity: proximal aspect.

The course and distribution of the median nerve in the wrist and hand is described on page 895.

Martin–Gruber connection

Multiple communicating branches between the median nerve (and sometimes the anterior interosseous nerve) arise proximally and pass medially between flexors digitorum superficialis and profundus, deep to the ulnar artery, and join the ulnar nerve. This motor fibre communication (commonly referred to as the Martin–Gruber connection) is estimated to be present in 17% of individuals. It results in a median nerve innervation of a variable number of intrinsic muscles of the hand (Leibovic & Hastings 1992), and presumably explains why isolated ulnar and median nerve lesions can sometimes be unpredictable in terms of the pattern of intrinsic muscle paralysis.

Branches in the forearm

Anterior interosseous nerve

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome

The anterior interosseous nerve may be affected with the median nerve or by itself in any of the causes of pronator syndrome (p. 836). Median nerve compression is typically caused by pressure from fascial bands on the deep head of the pronator teres or the tendinous radial attachment of flexor digitorum superficialis. Anterior interosseous nerve palsy may be due to external pressure, a form of ‘Saturday night palsy’, and sometimes by tight grip in association with pronation without obvious cause. It may be a manifestation of neuralgic amyotrophy and tends to resolve spontaneously over several months. A variety of aberrant muscles, e.g. an accessory head of flexor pollicis longus, palmaris profundus, or flexor carpi radialis brevis, have all been described as causing entrapment neuropathy of the anterior interosseous nerve.

Ulnar nerve

The ulnar nerve descends on the medial side of the forearm, lying on flexor digitorum profundus (Fig. 49.13, Figs 49.16–49.19). Proximally it is covered by flexor carpi ulnaris: its distal half lies lateral to the muscle and is covered only by skin and fasciae. In the upper third of the forearm, the nerve is distant from the ulnar artery, but more distally it comes to lie close to the medial side of the artery. About 5 cm proximal to the wrist it gives off a dorsal branch which continues distally into the hand, anterior to the flexor retinaculum on the lateral side of the pisiform and posteromedial to the ulnar artery. It passes deep to the superficial part of the retinaculum (in Guyon’s canal) with the artery and divides into superficial and deep terminal branches.

The course and distribution of the ulnar nerve in the hand is described on page 897.

Radial nerve

There is some variation in the level at which branches of the radial nerve arise from the main trunk in different subjects (Fig. 49.12, Fig. 49.13, Fig. 49.17, Fig. 49.18). Branches to extensor carpi radialis brevis and supinator may arise from the main trunk of the radial nerve or from the proximal part of the posterior interosseous nerve, but almost invariably above the arcade of Frohse.

Radial tunnel syndrome is an entrapment neuropathy of the radial nerve near the elbow, where four structures can potentially cause compression of the nerve. These are fibrous bands (which can tether the radial nerve to the radiohumeral joint); the sharp tendinous medial border of extensor carpi radialis brevis; a leash of vessels from the radial recurrent artery as it passes to supply brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis longus; the arcade of Frohse, which is the free aponeurotic proximal edge of the superficial part of supinator (see Fig. 48.6).

Superficial terminal branch

Radial sensory nerve entrapment (Wartenberg’s disease)

Entrapment of the superficial radial nerve can occur as the nerve emerges from beneath the edge of the brachioradialis tendon about 6 cm proximal to the radial styloid; it is probably pinched by the scissoring effect of brachioradialis and extensor carpi radialis brevis tendons. The condition is frequently associated with previous trauma in this region. The symptoms are pain and paraesthesia over the radial aspect of the dorsum of the wrist and hand.

Posterior interosseous nerve

The posterior interosseous nerve is the deep terminal branch of the radial nerve (Fig. 49.15, Fig. 49.16). It reaches the back of the forearm by passing round the lateral aspect of the radius between the two heads of supinator. It supplies extensor carpi radialis brevis and supinator before entering supinator: as it passes through the muscle it supplies it with additional branches. The branch to extensor carpi radialis brevis may arise from the beginning of the superficial branch of the radial nerve. As it emerges from supinator posteriorly, the posterior interosseous nerve gives off three short branches to extensor digitorum, extensor digiti minimi and extensor carpi ulnaris, and two longer branches, a medial to extensor pollicis longus and extensor indicis, and a lateral which supplies abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis. The nerve at first lies between the superficial and deep extensor muscles, but at the distal border of extensor pollicis brevis it passes deep to extensor pollicis longus and, diminished to a fine thread, descends on the interosseous membrane to the dorsum of the carpus. Here it presents a flattened and somewhat expanded termination or ‘pseudoganglion’, from which filaments supply the carpal ligaments and articulations. Articular branches from the posterior interosseous nerve supply carpal, distal radio-ulnar and some intercarpal and intermetacarpal joints. Digital branches supply the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints.

Medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm

The medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm has already divided into anterior and posterior branches before it enters the forearm (see Fig. 45.15). The larger anterior branch usually passes in front of, occasionally behind, the median cubital vein, and descends anteromedially in the forearm to supply the skin as far as the wrist. It curves round to the back of the forearm, descending on its medial border to the wrist, supplying the skin. It connects with the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm, the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm, and the dorsal branch of the ulnar nerve.

Lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm

The lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm is a direct continuation of the musculocutaneous nerve as it lies lateral to the biceps tendon in the antecubital fossa (see Figs 45.10 and 45.15). It passes deep to the cephalic vein, descending along the radial border of the forearm to the wrist. It supplies the skin of the anterolateral surface of the forearm and connects with the posterior cutaneous nerve of the forearm and the terminal branch of the radial nerve by branches which pass around its radial border. Its trunk gives rise to a slender recurrent branch which extends along the cephalic vein as far as the middle third of the upper arm, distributing filaments to the skin over the distal third of the anterolateral surface of the upper arm close to the vein. At the wrist joint the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm is anterior to the radial artery. Some filaments pierce the deep fascia and accompany the artery to the dorsum of the carpus. The nerve then passes to the base of the thenar eminence, where it ends in cutaneous rami. It has branches which connect with the terminal branch of the radial nerve and the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve.

Cormack GC, Lamberty BGH. The Arterial Anatomy of Skin Flaps. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1994.

Leiber RL, Jacobson MD, Fazeli BM, Abrams RA, Botte MJ. Architecture of selected muscles of the arm and forearm: anatomy and implications for tendon transfer. J Hand Surg. 1992;17A:787-798.

Leibovic SJ, Hastings HII. Martin-Gruber revisited. J Hand Surg. 1992;17A:47-53.

Salmon M. Anatomic studies. In: Taylor GI, Razaboni RM. Book 1. Arteries of the Muscles of the Extremities and the Trunk. Book 2: Arterial Anastomotic Pathways of the Extremities. St Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing, 1994.

Sheetz KK, Bishop AT, Berger RA. The arterial blood supply of the distal radius and ulna and its potential use in vascularized pedicled bone grafts. J Hand Surg. 1995;20A:902-914.

Tan ST, Smith PJ. Anomalous extensor muscles of the hand: a review. J Hand Surg. 1999;24A:449-455.