CHAPTER 11 Fluoroscopically guided fine bore intubation

Background

The UK National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) has reported that approximately 500 000 fine bore feeding tubes are distributed annually within the National Health Service (NPSA, 2005). The vast majority of nasogastric intubations are uncomplicated and dealt with by suitably trained practitioners within the ward environment. Patients requiring fine bore intubation for nutritional support are by virtue of the requirement to be intubated, unwell and vulnerable to complications from misplaced intubations or the distress of repeated attempts.

The NPSA reported that they were aware of 11 deaths between 2002 and 2004 resulting from misplaced nasogastric (NG) tubes and, since that time, the NPSA Patient Safety Bulletin has reported a further five deaths and four near misses from misplaced nasogastric tubes (NPSA 2005, 2007).

Accurate information is sparse as to the nature and number of complications associated with fine bore intubation; however, from the serious complications reported to the NPSA, misreading of x-ray checks is a significant factor and it is suggested that interpretation of these images must be carried out by practitioners trained to report them (NPSA, 2005).

Checking intubation siting

There are numerous tests to check the position of the tube tip. Some, such as auscultation or the use of blue litmus paper to test acidity/alkalinity, have been discredited (NPSA, 2005).

In the ward environment, the measurement of the pH of gastric aspirate is currently considered the safest and easiest repeatable means of confirming the siting of a fine bore tube in the stomach. However, gastric pH can be above 5.5 in a number of circumstances, falsely suggesting that the tube might not be in the stomach, for example in patients taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), patients who have pernicious anemia, or who have had a recent fluid intake. The type of fluid, feeding formulae or medication is also relevant (Stroud et al., 2003; Bain, 2005).

Endoscopy can be used to insert fine bore tubes when blind intubation on the ward has failed, although local anesthesia to the pharynx and sedation may be required; additionally, the tube can be dragged back upon removal of the endoscope. In normal circumstances, endoscopically guided fine bore tube insertion could be considered excessive. Diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy has associated complications. Quine and Bell (1995) indicated a mortality and morbidity in the region of 1:12 000 and 1:230 respectively and, more recently, the British Society of Gastroenterology figures reported by Teague (2003) suggested little change.

In discussing the thoracic and non-thoracic complications of gastric and enteric intubation, Pillai et al. (2005) refer to the radiographic check of tube placement as continuing to be the ‘gold standard’.

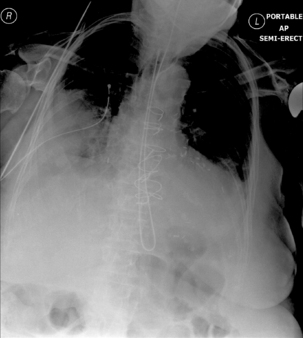

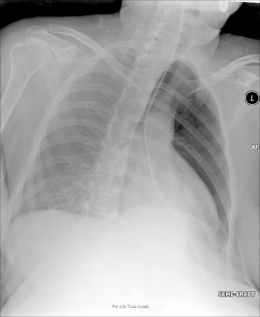

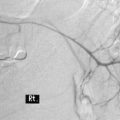

Radiography provides a snapshot of the fine bore tube position at the time of the x-ray, accurately identifying the site of misplaced tube tips (Figures 11.1, 11.2, 11.3 and 11.4).

Figure 11.3 Tube tip passed via right bronchus penetrating the pleural cavity – associated pneumothorax.

However, inexperience in image interpretation can lead to the misreading of tube siting. The benefits of fluoroscopy are shown in a case where misinterpretation of chest radiographs on an unconscious patient in a high dependency unit led to a number of failed blind and endoscopic intubations. The tube was considered repeatedly to be sited in the right side of the chest (Figure 11.5). Fluoroscopic tube guidance and the careful infusion of a water-soluble contrast medium demonstrated a redundant loop of colon and a strictured cologastric anastomosis. The appearance is of a late onset complication from a previous colonic interposition for esophageal atresia of which the clinical team were unaware (Figure 11.6) (Law, 2006).

Radiographer and radiologic technologist involvement

Price and Le Masurier (2007) suggest that 80% of District General Hospitals in the UK have radiographers performing DCBE examinations. Radiography provides an accurate snapshot of the fine bore tube position at the time of the x-ray. As long as the tube is radiopaque, a skilled practitioner can provide accurate information as to whether the tube is in the stomach or not. However, this raises the question of what should happen when an x-ray shows the tube is not correctly placed: should patients return to wards for tube resiting?

Radiographers skilled in GI fluoroscopy are ideally positioned to provide an intubation service and can quickly and easily acquire expertise in nasogastric/enteric intubation. With the wide potential for gaining experience, radiographers may well succeed with nasogastric intubating without recourse to fluoroscopy even if blind intubation on the ward has been unsuccessful.

For correctly positioned tubes:

The role of the clinical radiographer might include:

Fluoroscopically guided intubation of nasoenteric fine bore tubes is a safe and effective technique (Prager et al., 1986; Law, 1990). A core team of radiographers or radiologic technologists skilled in GI fluoroscopy developing expertise in siting problematic fine bore tubes, have the potential to offer major positive changes regarding intubation and to offer the development of a more flexible service.

Tube wire requirements

Fundamental to any intubation, problematic or otherwise, is the design of the fine bore (FB) tube (Law and Longstaff, 1992). The following features should be considered when selecting an FB tube (Box 11.1):

Nasopharyngeal intubation

Intubation of a critically ill patient (for example, one who has a serious base of skull fracture) will be aided by the use of a ‘C’ arm to enable horizontal beam lateral screening. This enables the passage of the tube across the posterior border of the nasopharynx to be observed.

Conventional fluoroscopy can be used in the majority of cases. Where the patient is able to turn, lateral imaging can assist when blind naso- or oropharyngeal intubation has been problematic and direct guidance is required (Box 11.2).

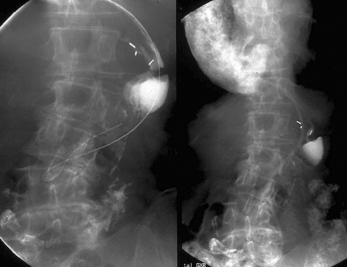

There is always a chance of pharyngeal pathology, such as a pouch, which can be intubated, with the attendant risk of rupture by the tube (Stroud et al., 2003). However, with care, the pouch can often be by-passed. Large pouches can impress on the esophagus. This can be confirmed with the patient swallowing a water-soluble contrast medium and, if necessary, occluding the pouch neck with a Foley balloon which also helps deviate the tube into the esophagus (Birchall and Law, 1987) (Figures 11.7 and 11.8).

The vast majority of trans-naso-esophageal intubations are straightforward and able to be dealt with within the ward environment. Contraindications or occasions where caution must be applied should be considered whether intubation is blind or fluoroscopically guided (Box 11.3).

Trans-esophageal intubation

Normally, once the esophagus has been intubated, onward passage into the stomach occurs without incident; however, the normal gastric fundus can produce a prominent posterior ballooning. A fine bore tube can loop in the fundus. If the tube does not have a hydrophilic coating, looping can make it difficult to remove the stylet. Even if a tube has a hydrophilic coating, ballooning of the fundus can cause problems in passing the tube into the gastric antrum.

With the patient supine, withdraw the stylet to the gastro-esophageal (GO) junction, advance the tube until a long loop is passed into the gastric antrum. It does not matter that the tube tip is still lodged and looped in the fundus. Maintaining the stylet at the GO junction, gently withdraw the tube until the looping in the fundus is uncoiled. Advance the stylet to the apex of the loop in the antrum, then, using a paradoxical movement, gently withdraw the tube back over the stiletto until the tip flicks forward, then advance both together.

Perforation

Using a non-ionic hypo-osmolar water-soluble contrast medium (such as Ultravist 240) to identify the location of the lesion, the patient may require turning so that the side of the lesion is raised and the tube lies on the dependent wall as it passes the site of the leak (Figure 11.9).

Hemangioma and esophageal varices

Inserting a tube past lesions that have the propensity to bleed profusely should only be undertaken following considered discussion and then with great care (Stroud et al., 2003).

Hiatus hernia

A hiatus hernia is not an uncommon occurence; slightly less common is when the hernia is volved and incarcerated. To circumvent this type of hernia with an FB tube, it may be of value for a contrast agent, such as dilute barium or Gastromiro, to be swallowed by the patient or infused to outline the intrathoracic stomach.

Turning the patient may be required to enable the barium to be passed around the gastric loop. The tube is passed around the initial gastric curve, adjusting the stylet as required, then further advanced to the diaphragmatic hiatus. With a final advancement of the stylet, the tube is passed through the diaphragmatic hiatus (Figure 11.10).

Benign stricturing

Examples include achalasia, fibrotic and postoperative stricturing. As much the complication to intubation in these circumstances as passage through the stricture is tube coiling within the distended esophagus or stomach.

Malignant stricturing

It is important to have full knowledge of the tract through a malignant stricture whether intubation is for fine bore feeding or as a part of a stent (SEMS) deployment (Law, 2008). The patient either swallows a mouthful of barium or it is infused through the tube when sited at the proximal end of the lesion. The lumen through a neoplastic stricture can often be tortuous and there is always the concern as to the presence of fistulous tracts.

Often, an 8 Fg fine bore tube can be passed into and through a stricture. If passage proves problematic, maintain the tube at the proximal end of the stricture and advance a 260 cm 0.35 ‘Jag’ wire which may be fine and soft enough to be fed through the stricture. Subsequently, railroad the tube over the wire. A Lunderquist torque control wire might be considered, replacing the stylet within the NG tube to improve manipulative capability. Open ended tubes, such as the 5 Fg Van Andel exchange cannula or straight or angled Cordis type catheter, can allow tube access through a particularly problematic stricure. Use a stiff guide wire exchange if a tube is required to be passed beyond the lesion (Figure 11.11).

Anastomotic leaks. Perforated duodenal ulceration

Fluoroscopic visualization of an anastomotic leak or perforation should be undertaken using a water-soluble contrast agent, as this will aid tube guidance past the area of concern (Law, 1990). It is important that the tube is directed away from the leak or perforation. A soft tipped wire, such as the angled ‘Jag’, will assist in directing the passage of the tube (Figures 11.12 and 11.13).

Gastro-duodenal intubation

Fluoroscopically guided enteral intubation has a high success rate. Law et al. (2004) reported a success rate of 98% in a series of 1011 attempted intubations for enteroclysis.

Technique

Nasogastric intubation has already been discussed; subsequent small bowel access may be achieved with gentle forward probing, with the stylet withdrawn, in the region of the pylorus. If the tube appears to loop across the origin of the pylorus, insert the wire to put some spring tension on the tube and draw it back: it can ‘flip’ into the canal.

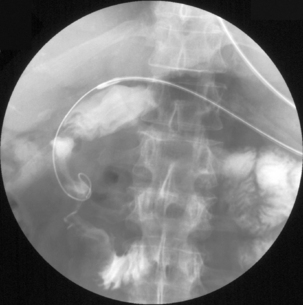

The main problem with intubation of the duodenum is that the line of the pylorus and duodenal bulb is not necessarily that which might be suggested from schematic representations of anatomy. Without over distending the stomach, the infusion of air will act as a contrast agent to outline the gastric lumen, pylorus and duodenum. It will also reduce the chance of the tube tip lodging in a ruggal folds. With air in the stomach and the stylet withdrawn approximately 10 cm, the more flexible distal end of the tube may be advanced and effectively ‘surfed’ on a gastric wave to the pyloric origin and, in many instances, on through into the duodenal bulb. The best viewing of the pylorus and air distended duodenal bulb may require the patient to turn into the right anterior oblique position (Figure 11.14).

Figure 11.14 Early image of a wire guided Crosby capsule showing the use of air contrast to outline the pylorus and duodenal bulb.

Duodenal obstruction may require intubation for diagnostic, nutritional or interventional purposes.

With the patient turned towards their right side, the liquid contrast agent has a greater chance of remaining in the second part of the duodenum. If the stricture is too tight for easy transgression, it would be worth considering a fine soft wire such as the ‘Jag’ via an open ended Law II tube. Once the passage of a wire has been achieved, the tube can be fed over the wire. If intubation were oro-enteric as a precursor to stenting, an ‘extra stiff’or ‘super stiff’ wire can subsequently be introduced via the tube (Figures 11.15, 11.16, 11.17 and 11.18).

Gastroduodenal obstruction will often result in fluid distending the stomach. The viscous nature of the gastric fluid will make tube manipulation more difficult and a likelihood of tube coiling. If intubation for diagnostic or nutritional purposes is required, a nasogastric drain should be considered. If a drainage tube is already in situ, it should be ascertained if it is likely to be removed, or whether endoscopy is to be undertaken in the near future. The removal of the drainage tube or endoscope is likely to extract the in situ fine bore tube. If stenting is to be undertaken through a fluid distended stomach, an endoscopic technique will most likely be required.

Complications associated with trans-nasal extubation

Although complications associated with extubation of fine bore tubes are uncommon, two that may occur are the knotting of an enteral tube that has migrated back into the stomach, or a tube tip that (due to its size and shape) lodges in the nasal concha. In both cases, extubation should not be forced. In the case of the tube lodging in the concha, it should be advanced on into the esophagus. A tube recovery can be undertaken with the patient placed on their side (with suction immediately available). A tongue depressor and pen torch are used to enable the tube to be viewed in the oropharynx. The tube is then grasped with long handled forceps, drawn out of the mouth and cut (while maintaining hold of the loop). The proximal end of the tube is then withdrawn through the nose and the distal length of tube can be removed transorally.

Cannulation via stoma, fistula and per rectum

Retrograde intubation can be of value for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes (Law, 2005). With retrograde intubation, a hypotonic agent is of value to relax peristalsis as well as allow contrast distension of the lumen. Use of retrograde intubation would include:

Birchall I.W.J., Law R.L. Balloon occlusion of pharyngeal pouch as aid to naso-enteric intubation. Br. Med. J.. 1987;294:1464.

Bain T. Testing nasogastric tube position: audit of three adult intensive care units. London: National Patient Safety Agency, 2005. (September)

Law R.L. The value of fluoroscopy as an aid to problematic intubation of fine bore feeding tubes. J. Interven. Radiol. 1990;5:171-173.

Law R.L. Abscess drainage as a part of a gastrografin enema. Radiography. 2005;11(4):286-289.

Law R.L. A surprise case of colonic interposition. Radiography. 2006;12(1):31-33.

Law R.L. Radiographer involvement with stent insertion to palliate symptomatic dysphagia resulting from neoplastic obstruction. Radiography. 2008;14:39-44.

Law R.L., Longstaff A.J. Technical report: a ‘new’ tube providing rapid insertion for the small bowel enema. Clin. Radiol.. 1992;45(1):35-36.

Law R.L., Slack N.F., Harvey R.F. Single contrast small bowel enteroclysis: the province of the radiographer? Clin. Radiol.. 2004;59(7):642.

Law R.L., Slack N.F., Harvey R.F. Radiographer performed single contrast small bowel enteroclysis. Radiography. 2005;11(1):11-15.

National Patient Safety Agency. [(February)]. Reduced harm caused by misplaced feeding tubes. National Patient Safety Agency, 2005. Newsline: www.npsa.nhs.uk

National Patient Safety Agency. [(April)]. Nasogastric tube incidents: update. 2007. Patient Safety Bulletin 3, www.npsa.uk/pso.

Pillai J.B., Vegar A., Brister S. Thoracic complications of nasogastric tube: review of safe practice. Interac. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2005;4:429-433.

Prager R., Laboy V., Venus B. Value of fluoroscopic assistance during transpyloric intubation. Crit. Care Med.. 1986;14(2):151-152.

Price R.C., Le Masurier S.B. Longitudinal changes in extended roles in radiography: a new perspective. Radiography. 2007;13(1):18-29.

Quine M.A., Bell G.D. Prospective audit of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in two regions of England: safety, staffing, and sedation methods. Gut. 1995;36:462-467.

Stroud M., Duncan H., Nightingale J. Guidelines for enteral feeding in adult hospital patients. Gut. 2003;52(7):1-12.

Teague R. Clinical practice guidelines update: safety and sedation during endoscopic procedures. British Society of Gastroenterology, 2003. Online: http://www.bsg.org.uk