CHAPTER 12 Fluoroscopic investigations of the small bowel

Introduction

When compared with the high technical standards expected of barium radiology of the upper gastrointestinal tract and the double contrast barium enema, small bowel imaging could be considered to be the poor relation. Maglinte et al. (1996) suggest that small bowel imaging has been ‘performed casually without attention to detail’, ‘for the sake of completeness’. That said, the strengths and weaknesses of barium examinations of the small bowel have all been thoroughly examined in the past and have stood the test of time. Although many of the papers on the subject were published in the 1990s, 1980s or even the 1970s, their conclusions are still relevant today.

Antes (2003) raised the concern that, with the decrease in frequency of barium examinations, ‘the art of performance and interpretation (of these examinations) might get lost’. The development of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) software has enabled cross-sectional imaging to establish a number of techniques to demonstrate the small bowel, but alternative modalities should only replace tried and tested techniques with caution.

Price and Le Masurier (2007) suggest that, in the UK, 80% of District General Hospitals now have radiographers performing barium fluoroscopy, predominantly the double contrast barium enema. Historically, small bowel radiology has been the province of radiologists, but Law et al. (2005) demonstrated that radiographer performance and reporting of small bowel enteroclysis (SBE) has a sensitivity and specificity comparable to published standards.

Unlike upper and lower GI tract investigations, the radiological approach to investigating the small bowel is not well defined and local preference and expediency is more closely involved in the equation to determine what is considered acceptable and best practice. Departments that routinely perform small bowel enteroclysis are still in the minority (Ha et al., 2004).

Bowel preparation

It is not necessary to have the right colon as clear as you might wish for a double contrast barium enema, although marked fecal residue in the ascending colon can inhibit the passage of barium through the distal small bowel and ileocecal valve. A degree of clearance might also enable gross pathology affecting the iliocecal valve or proximal colon to be identified (Law, 1983; Nolan and Traill, 1997).

Flocculation

To maintain barium in suspension, manufacturers provide the barium particles with a protective coating, maintaining them in a separate state from one another. Muco-proteins generated in the GI tract are absorbed by the barium particles and, if prolonged exposure occurs, the absorption breaks down the protective coating of the particles allowing them to clump together. This is known as flocculation.

In normal instances, there is a greater likelihood of flocculation occurring with the BaFT due to the slower transit of barium through the small bowel. Its occurrence is non-specific, but should flocculation occur during the more rapid transit of enteroclysis, there is a greater likelihood of flocculation being relevant to the diagnosis (Lomoschitz et al., 2003).

The per oral barium follow through (BaFT)

The BaFT examination is far more widely used to image the small bowel than enteroclysis. Toms et al. (2001) offered a number of reasons why the BaFT might be advocated:

Ha et al. (2004), in reviewing radiographic examinations of the small bowel and practice patterns in the USA, stated that the BaFT is the dominant small bowel examination in the USA. The main examination technique consists of over-couch radiographs (of the whole abdomen), which should be coupled with fluoroscopic spot images of the terminal ileum. However, the paper also states the BaFT technique advocated by the American College of Roentgenologists is fluoroscopy-dependent, with palpation of all accessible small bowel loops including the terminal ileum, with appropriate images to demonstrate any abnormality or representative images if no abnormality is demonstrated. The technique that is advocated can result in a more time-consuming examination. Maglinte et al. (1996) state that the BaFT as ‘conventionally performed has no place in the practice of cost effective medicine’. The use of the fluoroscopy-dependent BaFT technique is well supported (Maglinte et al., 1987, 1996; Ha et al., 2004).

The BaFT might be considered ‘safer’ and less invasive than the SBE and preferred by most patients as it does not require enteral intubation. Some practitioners consider the BaFT the examination of choice in known Crohn’s disease. In its simplest form, the least advocated BaFT technique requires minimal fluoroscopy room occupation and might thus be considered less labour intensive (Maglinte et al., 1987, 1996; Bernstein et al., 1997; Nolan and Traill, 1997; Toms et al., 2001).

Barium follow through technique

A considered barium solution might comprise 300 ml Baritop 100 (Sanochemia UK), diluted with 400 ml water (75%w/v), 10 ml Gastrografin and 6 sachets of Carbex granules. The combined use of the hyperosmolar Gastrografin and the effervescent agent Carbex can significantly reduce small bowel transit time without affecting the examination quality (Summers et al., 2007); 600 ml of solution is ingested in as short a time as the patient finds comfortable.

Once barium is in the colon, relaxing the bowel muscle by using an intravenous hypotonic agent has been reported as being of value (Bernstein et al., 1997). Focal images are taken of the terminal ileum and any identified abnormality as well as fluoroscopic or over-couch images taken to demonstrate an overview of the whole small bowel (Box 12.1).

BOX 12.1 Single contrast barium follow through technique

A solution of 300 ml of 100% barium (Baritop 100), 400 ml of water, 10 ml Gastrografin and 6 sachets of Carbex granules (23% w/v)

A solution of 300 ml of 100% barium (Baritop 100), 400 ml of water, 10 ml Gastrografin and 6 sachets of Carbex granules (23% w/v) If barium appears to be delayed, it may be due to air trapped within the small bowel; in these instances, it is worth considering intermittently turning the patient into the prone position to aid onward passage

If barium appears to be delayed, it may be due to air trapped within the small bowel; in these instances, it is worth considering intermittently turning the patient into the prone position to aid onward passageLimitations of the barium follow through

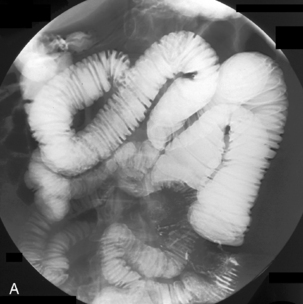

Nolan and Traill (1997) and Toms et al. (2001) suggest that because of the nature of the technique, a higher number of BaFT examinations require further investigation to confirm normality or otherwise. Good distension is not usually achieved therefore early strictures, subtle appearances and fine nodules are more likely to be missed.

Maglinte et al. (1987, 1996) report that the sensitivity and specificity of the BaFT is technique and operator dependent, although Maglinte et al. (1982) refer to diagnostic errors being more of a technical nature than perceptual.

Small bowel enema or enteroclysis (SBE)

The word enteroclysis derives from the Greek words ‘enteron’ meaning ‘intestine’ and ‘klysis’ meaning ‘a high enema’. Its use in the context of this examination is of uncertain origin but might be to disassociate from the word enema and the perception that rectal intubation will be required.

Despite advances in other imaging techniques and the limited popularity of small bowel enteroclysis, the SBE is widely accepted as currently being the optimum technique for examining the small bowel. The SBE is also commonly used as the reference point for other small bowel imaging methods (Maglinte et al., 1987, 1992; Nolan and Traill, 1997; Nolan, 1997; Antes, 2003).

The techniques of performing small bowel enteroclysis have evolved over 80 years. Pesquera (1929) published a technique using duodenal intubation as a means of infusing a barium, acacia and water mixture that enabled the demonstration of the whole small bowel. Sellink (1976) mentions Gershon-Cohen and Shay (1939), Scott-Harden et al. (1961) and Bilbao et al. (1967) who, among others, over the intervening years, advanced the development of techniques to examine the small bowel. In the 1970s, single contrast enteroclysis re-emerged, gaining popularity through the distillation of ideas and publications of advocates such as Sellink (1974) who consider the mitigating features of the SBE outweigh the arguments that are put forward against its use.

The patient experience

Principle of the single contrast SBE technique

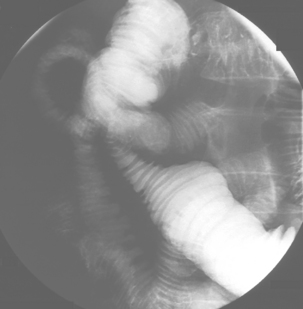

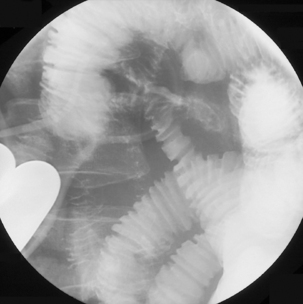

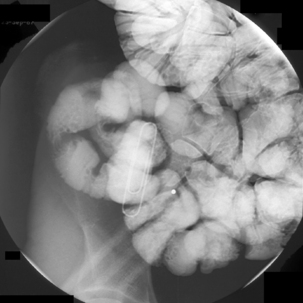

A low density barium suspension of around 20%w/v (such as 300 ml Baritop 100 diluted with 1500 ml water) is infused through the tube at a rate that allows a single column of barium to distend and pass through the small bowel to the colon (Figure 12.1).

Barium transit to the colon is reported as often being less than 35 minutes.

Optimum results are best achieved by:

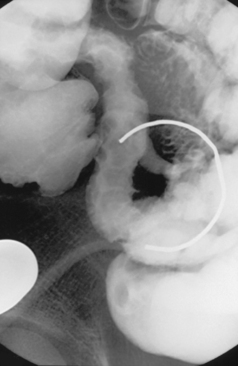

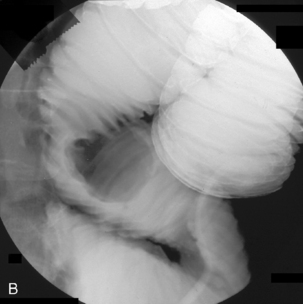

Figure 12.5 Terminal ileal Crohn’s disease with enterocolic fistulae and incidental Meckel’s diverticulum.

Spot images should be taken at appropriate times to record the whole of the distended small bowel and, in particular, the terminal ilium. More focused images should be taken to record any abnormality. If barium is in the colon, a cursory examination of the demonstrated large bowel can be of value (Figure 12.7) (Maglinte et al., 1982, 1996; Goei et al., 1988; Bessette et al., 1989; Nolan, 2000).

Advantages of the SBE

The SBE is widely reported as having a high sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value for small bowel stricturing and mucosal abnormalities (Barloon et al., 1994; Nolan, 2000). The SBE has also been reported as having a sensitivity of between 93% and 100% for Crohn’s disease (Maglinte et al., 1980, 1982, 1985, 1987, 1992, 1996; Bessette et al., 1989; Chen et al., 1991; Chernish et al., 1992; Link et al., 1993; Nolan, 1997; Nolan and Traill, 1997; Lappas and Maglinte, 1990; Cirillo et al., 2000; Mako et al., 2000; Reiber et al., 2000; Toms et al., 2001; Law et al.4, 2005).

The high negative predictive value of the SBE is also important in the exclusion of pathology. If the presence of small bowel Crohn’s disease is being questioned, further imaging is considered unnecessary in light of an SBE reported as normal by an experienced reviewer (Law et al., 2005).

Enteroclysis remains a primary investigation if clinically a Meckel’s diverticulum is suspected. Observing the flow of barium through the small bowel in conjunction with palpation can enable Meckel’s diverticulum to be identified (Figure 12.8).

Partial small bowel obstruction (SBO) is well demonstrated by enteroclysis. With high SBO, intubation is of value as fluid in the stomach or small bowel can be aspirated prior to barium infusion.

Critically ill or symptomatic, frail, elderly patients may well be unable to tolerate swallowing the volume of barium required for a BaFT, but can often tolerate barium infused through a tube. The SBE requires minimal movement and only one visit to the fluoroscopy room; additional confirmatory imaging is not normally required. The main clinical indications for the SBE are given in Box 12.2. The value of the SBE is tabulated in Box 12.3.

The enteroclysis tube

Intubation requires patient consent and compliance. The psychological preparation of the patient is important if maximum cooperation and a successful examination is to be obtained. An explanation of what is involved should be given by someone accredited to undertake the procedure. It has been suggested that poor patient tolerance is related to lack of operator experience not the technique (Maglinte et al., 1987, 1996).

The size of the tube lumen can affect patient comfort, ease of intubation and flow rate. Over the last twenty years, enteroclysis tube styles and dimensions have changed; in the 1990s tubes of 14 French gauge (Fg) were often employed, however, these sizes are now considered both uncomfortable and unnecessary. Tubes with tungsten weighted tips are also unnecessary, increasing patient discomfort and having a limited manipulative capability. Unweighted 10 Fg polyurethane tubes are considered to have a high intubation success rate with the minimum of discomfort (Goei et al., 1988; Nolan and Traill, 1997; Toms et al., 2001; Law et al., 2005).

If a patient has an indwelling gastric drainage tube, there is nothing to preclude an enteroclysis tube being inserted through the other nostril. Enteroclysis techniques can also be adapted to use a pre-existing enteral tube, the in situ tube negating the need to pass a specific enteroclysis tube. However, the practitioner must be aware of the type of tube in situ – if the tube has numerous side ports, barium might be infused into the stomach and not the small bowel. During extubation, attaching a 20 ml syringe with which to apply gentle suction will prevent barium in the lumen from draining into the nose or pharynx.

Contraindications

There are few absolute contraindications to intubation; these would include:

There are some relative contraindications to nasoenteric intubation and careful consideration should be given as to the justification, nature and approach to intubation (i.e. nasal or oral route); these would include:

Intubation

Check with the patient for any contraindications to intubation. To provide a degree of local anesthesia, the selected nostril is sprayed with 2% lidocaine prior to the insertion of a naso-enteric tube. The patient should be warned that the lidocaine has an unpleasant taste as it passes into the oropharynx and might smart, bringing tears to the eyes. Nasal intubation is to be preferred as it is normally easier. Once intubated the discomfort for the patient should subside (Halligan et al., 1994).

Care has to be taken that the tube tip follows the line along the roof of the hard palate as it can so easily rise into the nasal concha through which passage will be difficult and uncomfortable despite local anesthesia. Although the patient might feel the tube in the back of the throat, the direct downwards passage of the tube reduces gagging and the patient cannot bite the tube. Should the patient retch or vomit, the tube is less likely to be expelled (Dixon et al., 1993) and there is little hindrance to the patient swallowing and talking.

With the patient in the right lateral position, gas in the stomach will migrate into the fundus of the stomach making it significantly easier to pass the tip of the tube into the gastric body. If the stomach is devoid of air, try infusing 100 ml of air using a syringe. If there is a problem extricating the tube from the bowl of the gastric fundus, withdraw the wire as far as the gastro-esophaeal junction and advance the tube. The tip becomes lodged against the wall and a tube loop extends into the distal body or antrum. Passing the wire to the apex of the formed tube loop and using a paradoxical movement, while keeping the wire in position, gradually withdraw the tube over the wire until the tip flips forward.

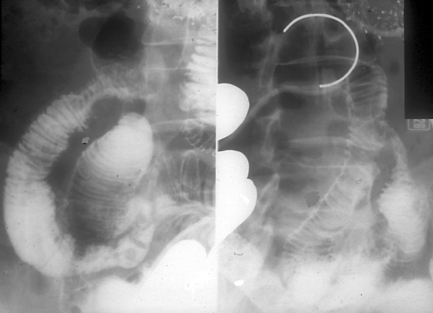

The lumen of some tubes, such as the one described by Law and Longstaff (1992), has the advantage of a hydrophilic coating that allows ease of interplay between the tube and its guide wire. Tube length is also important as it should be enough to enable passage through complex anatomy such as a volved incarcerated hiatus hernia (Figure 12.9) or a distensile stomach.

With the tube in the gastric body, turn the patient supine and then to the right anterior oblique; air will now migrate towards the pylorus. With interplay between the tube and guide wire, the tube tip can ‘ride’ a peristaltic wave to the pylorus. The direction of the pyloric canal and duodenal bulb can alter significantly in position and it is worth observing air passage through the pylorus. If visualization is difficult, with the patient supine and the guide wire fully inserted, infuse 20 ml of dilute barium instead. If during passage the tube tip lodges in a small bowel fold or against the aortic impression, or as it passes through the third part of the duodenum, a 20 ml bolus of air will distend the lumen and, in most cases, dislodge the tube tip, enabling it to migrate to the duodenal-jejunal flexure. Should intubation still be unsuccessful, it may be because of occluding pathology (Figures 12.10, 12.11A, 12.11B) (see Chapter 11 for a detailed look at fine bore intubation).

Infusion techniques

Three methods are commonly used to infuse barium (Sellink, 1974; Maglinte et al., 1987; Goei et al., 1988).

Hydrostatic infusion: a bag of barium on a drip stand is connected to the naso-enteric tube. Raising and lowering the drip stand increases and reduces the infusion rate. If necessary, improved infusion pressure can be achieved by attaching a pressure cuff to the bag.

Infusion pumps: using an enteroclysis infusion pump, such as the one marketed by ‘Guerbet’ (Figure 12.12), barium can be infused through a 10 Fg tube enabling a continuous column of barium to distend and pass through the small bowel with no untoward jet effect. Flow can be optimized enabling immediate and measured adjustment of flow rate to adapt and respond to the peristaltic action and barium passage through the small bowel (Maglinte et al., 1987; Goei et al., 1988; Halligan et al., 1994; Nolan and Traill, 1997; Toms et al., 2001; Law et al., 2005).

When using syringe infusion, the rate of flow is not usually a problem unless the bowel is obstructed. Hydrostatic and pump infusion should start slowly (50–60 ml/min) until peristalsis has initiated antegrade barium passage, at which point flow rate can be increased as appropriate to provide a distended single column. Flow rates in excess of 100 ml/min are not uncommon. If the flow rate is too high, the bowel lumen will become hypotonic. If hypotonia should occur, the barium infusion must be halted until peristalsis recommences.

Small bowel enteroclysis using methyl cellulose

Nolan and Traill (1997) describe a technique popularized by Herlinger (1978) in which an ultra low density double contrast effect can be produced by the infusion of 160–200 ml of 80–100% w/v barium sulfate, followed by up to 2000 ml of 0.5% aqueous solution of methyl cellulose (MC). Maglinte et al. (1987) also suggest a ‘biphasic technique’ variation for using MC; this involves infusing 400–500 ml of 50% w/v barium, performing a single contrast SBE followed by up to 2000 ml of MC.

The advantages offered by advocates of this technique include good mucosal detail offered by MC and, at the same time, the ability to view, palpate and image any abnormal segments demonstrated in single contrast by the header column. It has also been reported that MC aids in the evacuation of the contrast (Maglinte et al., 1987; Nolan and Traill, 1997).

Disadvantages of techniques using MC include the fluoroscopy and room time required to ‘double view’ the small bowel, initially in single then in double contrast. If MC gets ahead of the column of barium, from that point on, the diagnostic quality of the examination is compromised. This is particularly relevant when considering the frequency of distal ileal pathology such as Crohn’s disease. There is no strong evidence that the use of MC greatly increases the diagnostic capability of the examination over that of the single contrast SBE. An oral version associated with the BaFT has been reported in which the ingestion of 200 ml of 70% w/v barium is followed by 600 ml of 0.5% MC (Ha et al., 1998).

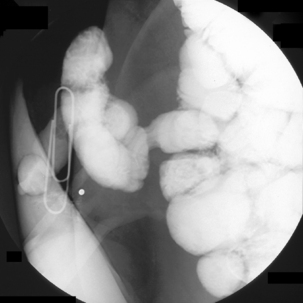

Ileostomy enteroclysis

On occasion, the small bowel needs to be assessed in a patient with an ileostomy. If there is no known disruption to the small bowel, conventional enteroclysis can be performed. Bowel preparation for enteroclysis in the presence of an ileostomy should not include any purgation. With the patient in the supine position, it can assist with identifying the location of the ileostomy by taping a paperclip over the stoma site (Figure 12.13). The stoma and prestomal bowel is best viewed tangentially with the patient turned towards the right; in this way, prestomal strictures or parastomal hernia can best be identified (Figure 12.14). Inflammation in the prestomal small bowel is best seen with ileoscopy.

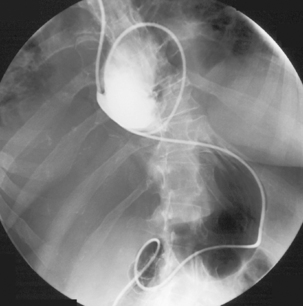

If there is surgical or pathological disruption to the small bowel preventing the imaging of the more distal bowel, retrograde imaging can be undertaken (Zagoria et al., 1986) (Figures 12.15 and 12.16).

With the patient supine, a small slit is made in the ileostomy bag towards the midline side (so that any expelled barium is contained). An unweighted 8 Fg 140 cm fine bore tube with a hydrophilic coated lumen is inserted into the stoma lumen and advanced as far as possible. Partially withdrawing the guide wire and using an interplay between tube and wire will enable the tip of the tube to be advanced. Intermittent pulsed fluoroscopy will identify tube site; dilute barium can be infused to demonstrate the direction of the small bowel lumen. Both intubation and enteroclysis are markedly assisted by the use of an intravenous hypotonic agent, not only does it ease retrograde infusion of barium but it also limits the risk of barium expulsion. If needed, suction can be used to remove any barium draining into the bag.

The use of air double contrast in the small bowel

With both antegrade and retrograde air insufflation, the patient may experience colicky abdominal pain and require analgesia. Because of the numerous overlapping small bowel loops, the quality standards associated with the double contrast barium enema cannot be applied to the small bowel. Although it has been reported that air contrast can highlight aphthous ulcers, strictures can be missed with the use of air contrast (Nolan and Traill, 1997; Ha et al., 2004).

Antegrade: the introduction of air following barium as part of enteroclysis can provide good demonstration of the jejunum, although imaging of the mid/distal ileum may be inadequate, with poor demonstration of the clinically more problematic terminal ileum (Maglinte et al., 1987).

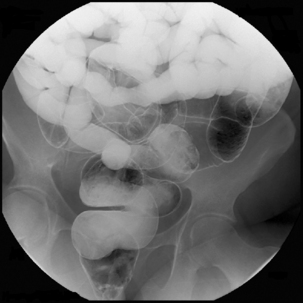

Retrograde: when a BaFT offers poor visualization of the terminal ileum, improved imaging is possible by the retrograde introduction of air after injecting a hypotonic agent such as Buscopan or glucagon. A rectal tube is inserted and the colon insufflated with air. Turning the patient allows air to migrate to the right colon and, in many instances, reflux through the ileocecal valve. A clean colon is desirable both to ease the passage of gas around the colon as well as reduce fecal reflux into the ileum (Nolan and Traill, 1997; Ha et al., 2004).

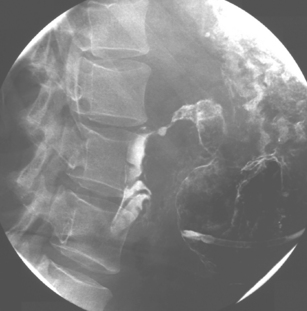

Post colectomy and ileorectal anastomosis: retrograde SBE is of particular benefit if pelvic small bowel adhesions are suspected following an ileorectal anastomosis. The examination requires the introduction of a double contrast enema tip and the IV injection of a hypotonic agent. A low density barium is hydrostatically infused per rectum. The subsequent introduction of air can be of value within the limits of patient comfort (Figure 12.17); however, retrograde imaging of the complete small bowel is not to be routinely advocated.

Gastrografin follow through

One hundred milliliters of the hyperosmolar contrast medium ‘Gastrografin’ is given to the patient (orally or via a nasogastric tube), with an initial check abdominal x-ray being taken most commonly at 4–6 hours. If contrast has reached the colon within 24 hours, the patient is considered to have an incomplete (subacute) obstruction. The technique is safe and was found to reduce the need for surgical intervention in several studies (Choi et al., 2005, 2006; Al Salamah et al., 2006).

Complications associated with the SBE

Complications associated with naso-enteric intubation are covered in Chapter 11. Additional complications associated with barium infusion are likely to be vomiting and colic. Vomiting can occur if the infusion rate of the contrast is greater than the ability of peristalsis to initiate its onward passage into the small bowel, resulting in gastric reflux. Barium reflux can be overcome by reducing the infusion rate and, if necessary, turning the patient onto their right side to facilitate gastric drainage.

Al Salamah S.M., Fahim F., Mirza S.M. Value of water soluble contrast (meglumine amidotrizoate) in the diagnosis and management of small bowel obstruction. World J. Surg.. 2006;30(7):1290-1294.

Antes G. Barium examinations of the small intestine and colon in inflammatory bowel disease. Radiologe. 2003;43(1):9-16.

Barloon T.J., Lu C.C., Honda H., et al. Does a normal small-bowel enteroclysis exclude small-bowel disease? A long-term follow-up of consecutive normal studies. Abdom. Imaging. 1994;134(5):925-932.

Bernstein C.N., Boult I.F., Greenberg H.M., et al. A prospective randomized comparison between small bowel enteroclysis and small bowel follow-through in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(2):390-398.

Bessette J.R., Maglinte D.D., Kelvin F.M., et al. Primary malignant tumors in the small bowel: a comparison of enema and conventional follow through examination. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1989;153:741-744.

Bilbao M.K., Frische L.H., Dotter C.T., et al. Hypotonic duodenography. Radiology. 1967;89(3):438-443.

Chen M.Y., Ott D.J., Kelley T.F., et al. Impact of the small bowel study on patients’ management. Gastrointest. Radiol.. 1991;16(3):189-192.

Chernish S.M., Maglinte D.D., O’Connor K. Evaluation of the small bowel by enteroclysis for Crohn’s disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol.. 1992;87:696-701.

Choi H.K., Chu K.W., Law W.L. Therapeutic value of Gastrografin in adhesive small bowel obstruction after unsuccessful conservative treatment: a prospective randomised trial. Ann. Surg.. 2006;236(1):1-6.

Choi H.K., Law W.L., Ho J.W., et al. Value of Gastrografin in adhesive small bowel obstruction after unsuccessful conservative treatment: a prospective evaluation. World J. Gastroenterol.. 2005;11(24):3742-3745.

Cirillo L.C., Camera L., Della Noce M., et al. Accuracy of enteroclysis in Crohn’s disease of the small bowel: a retrospective study. Eur. Radiol.. 2000;10(12):1894-1898.

Dixon P.M., Roulston M.E., Nolan D.J. The small bowel enema: a ten year review. Clin. Radiol.. 1993;47(1):46-48.

Gershon-Cohen J., Shay H. Barium enteroclysis: a method for the direct immediate examination of the small intestine by single and double contrast technique. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1939;82:965.

Goei R., Lamers R.J., Lamers J.J. Enteroclysis: improved performance using a flow inducer. Acta Radiol.. 1988;29(6):665-668.

Ha H.K., Park K.B., Kim P.N., et al. Use of methyl cellulose in small bowel follow-through examination: comparison with conventional series in normal subjects. Abdom. Imaging. 1998;23(3):281-285.

Ha A.S., Levine M.S., Rubesin S.E., et al. Radiographic examination of the small bowel: survey of practice patterns in the United States. Radiology. 2004;231(2):407-412.

Halligan M.S., Jobling J.C., Bartram C.I. Benefits of intravenous muscle relaxants during barium follow through. Clin. Radiol.. 1994;49:179-182.

Herlinger H. A modified technique for the double-contrast small bowel enema. Gastrointest. Radiol.. 1978;3(2):201-207.

Lappas J.C., Maglinte D.D. Enteroclysis – a technique for examining the small bowel. CRC Crit. Rev. Diagn. Imaging. 1990;30(2):183-217.

Law R.L. The small bowel enema. Radiography. 1983;49:91-95.

Law R.L., Longstaff A.J. Technical report: a ‘new’ tube providing rapid insertion for the small bowel enema. Clin. Radiol.. 1992;45(1):35-36.

Law R.L., Slack N., Harvey R.F. Radiographer performed single contrast small bowel enteroclysis. Radiography. 2005;11:11-15.

Link T.M., Koc F., Peters P.E. State of the art of selective small bowel enema. (Indications and results). Radiologe. 1993;33(6):343-346.

Lomoschitz F., Schima W., Schober E., et al. Enteroclysis in adult celiac disease: diagnostic value of specific radiographic features. Eur. Radiol.. 2003;13(4):890-896.

Maglinte D.D., Burney B.T., Miller R.E. Lesions missed on small bowel follow through. Radiology. 1982;144(4):737-739.

Maglinte D.D., Chernish S.M., Kelvin S.M., et al. Crohn’s disease of the small intestine: accuracy and relevance of enteroclysis. Radiology. 1992;184:541-545.

Maglinte D.D., Elmore M.F., Chernish S.M., et al. Enteroclysis in the diagnosis of chronic unexplained gastrointestinal bleeding. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1985;28(6):403-405.

Maglinte D.D., Elmore M.F., Isenberg M., et al. Meckel diverticulum: radiological demonstration by enteroclysis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1980;134(5):925-932.

Maglinte D.D., Kelvin F.M., O’Connor K., et al. Current status of small bowel radiography. Abdom. Imaging. 1996;3:247-257.

Maglinte D.D., Lappas J.C., Kelvin F.M., et al. Small bowel radiography: how, when, why? Radiology. 1987;163:297-305.

Mako E.K., Mester A.R., Tarjan Z., et al. Enteroclysis and spiral CT in diagnosis and evaluation of small bowel Crohn’s disease. Eur. J. Radiol.. 2000;35:168-175.

Nolan D.J. The true yield of the small intestine barium study. Endoscopy. 1997;29:447-453.

Nolan D.J. Enteroclysis of non-neoplastic disorders of the small intestine. Eur. Radiol.. 2000;10:342-353.

Nolan D.J., Traill Z.C. The current role of the barium examination of the small intestine. Clin. Radiol.. 1997;52:809-820.

Pesquera G.S. Method for direct visualisation of lesions in small intestine. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1929;22(3):254-257.

Price R.C., le Masurier S.B. Longitudinal changes in extended roles in radiography: a new perspective. Radiography. 2007;13(1):18-29.

Reiber A., Wruk D., Potthast S., et al. Diagnostic imaging in Crohn’s disease: comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and conventional imaging methods. Int. J. Colorectal Dis.. 2000;15:176-181.

Scott-Harden W.G., Hamilton H.A., Smith S.M. Radiological investigation of the small bowel. Gut. 1961;2:316-322.

Sellink J.L. Radiological examinations of the small intestine. Acta Radiol.. 1974;15:318.

Sellink J.L. Radiological atlas of common diseases of the small bowel. Stenfert Kroese, 1976;59-61.

Summers D.S., Roger M.D., Allan P.L., et al. Accelerating the transit time of barium sulphate suspensions in small bowel examinations. Eur. J. Radiol.. 2007;62(1):122-125.

Toms A.P., Barltrop A., Freeman A.H. A prospective randomised study comparing enteroclysis with small bowel follow-through examinations in 244 patients. Eur. Radiol.. 2001;11:1150-1160.

Zagoria R.J., Gelfand D.W., Ott D.J. Retrograde examination of the small bowel in patients with an ileostomy. Gastrointest. Radiol.. 1986;11(1):97-101.