CHAPTER 13 Fluoroscopic investigations of the large bowel

Introduction

Halligan et al. (2003) and Halligan (2004) have suggested that ‘a barium enema list is not the attractive proposition it once was’ and that ‘radiologists, both trainees and consultants, are less inclined to take an interest’ in barium enema; in addition, the lack of interest is compounded by the perception that the examination is ‘old fashioned and behind the cutting edge of imaging’. The belief that the sensitivity of the double contrast barium enema (DCBE) for colorectal cancer (CRC) is poor at only about 85% adds to the lukewarm view of the examination. Indeed, Shorvon (2003) implied that there is no room for improving the DCBE and that it is ‘on a developmental plateau’.

It has been suggested by Glick (1997) that there has been a bias against the DCBE associated with a number of studies in which 75–95% of missed cancers were perceptive errors rather than technical error. This finding would suggest that many of the possible shortcomings of the DCBE examination could be overcome by double reading.

However, it is possible to achieve a very high sensitivity if appropriate attention is given to technique. It may be the case that the image sequence of the DCBE has been optimized, but fluoroscopy equipment continues to improve and is now producing higher quality images at a fraction of the radiation dose required just a few years ago.

In the USA, the DCBE was considered to detect the majority of clinically important lesions and was therefore deemed to be an appropriate method for colorectal cancer screening (Winawer et al., 1997). These considerations were supported by the American College of Gastroenterology, The American Association of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. A survey of US radiologists, published in 2002, indicated that 75% believe the DCBE to be a ‘very effective’ colorectal cancer screening procedure and, at that time, Medicare approved DCBE as a CRC screening modality in the USA (Klabunde et al., 2002). Ciatto and Castiglione (2002), in reviewing the use of the DCBE within a screening program, also concluded that DCBE was a useful adjunct to screening colonoscopy.

Complications

Vora and Chapman (2004) reviewed 348 000 barium enemas performed by 59 radiographers; 89 complications were reported (1:3900) including five deaths (a mortality rate of 1:70 000). Culpan and Chapman (2002) reported on 54 complications in a review of 134 700 barium enema examinations performed over a 3-year period by 250 radiographers who had attended the Leeds barium enema training course. The complication rate was 1:2500; three deaths indicated a mortality rate of 1:44 900.

The complication and mortality rates for radiographers are not dissimilar to those reported by Blakeborough et al. (1997a) in reviewing the responses of 756 UK consultant radiologists who had performed 738 216 barium enemas in a 3-year period. A total of 82 complications were reported by 77 radiologists (1:9000) including three deaths (a mortality rate of 1:56 786).

Complications associated with the barium enema include perforations, cardiac events and cerebrovascular accidents. In reviewing rectal perforation after a barium enema, de Freiter et al. (2006) report that the most catastrophic course with a high mortality rate develops from sepsis and peritonitis resulting from intraperitoneal perforation. Also reported as prognostically unfavorable is the venous intravasation of barium.

Comment was also made in this paper regarding the introduction of excessive intracolonic pressures, excessive colonic distension and also concern regarding the use of rectal balloon catheters. These results compare favorably with colonoscopy (de Freiter et al., 2006). Updating the British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines, Teague (2003) refered to previous audits including one by Quine et al. (1995) (in which the 30 day mortality was found to be 1:2000) and he indicated there was no evidence to suggest that mortality rates had improved significantly since the 1990s.

Radiologic technologist and radiographer involvement

Price and Le Masurier (2007) reported results of a study that suggest radiographers are performing barium enema examinations in as many as 80% of district general hospitals (DGHs) in the UK. In the USA, Thompson et al. (2006) reported that, with training, radiologic technologists can perform and interpret fluoroscopic images as effectively as radiologists with a similar sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value. These results are also supported by Culpan et al. (2002) as well as Booth and Mannion (2005). A review on radiographer DCBE reporting by Law et al. (2008), demonstrating a 98% sensitivity to CRC, also strongly supports the view that examinations by radiographers can have a sensitivity and specificity similar to those carried out by radiologists.

Using smooth muscle relaxants

Hypotonia of the colon and rectum has a number of beneficial effects:

The rectal infusion of agents such as 30 ml of peppermint oil solution has been demonstrated to have an antispasmodic effect (Asao et al., 2003). The most commonly used hypotonic agents are 20 mg in 1 ml hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan) or 1 mg in 1 ml glucagon (Fink and Aylward, 1995; Goei et al., 1996). The IV injection of Buscopan is likely to have no effect on the diagnostic quality of the examination whether it is given before or after the infusion of barium (Elson et al., 2000).

It is not uncommon practice to avoid giving Buscopan in patients who have glaucoma, however, it has been reported by Fink and Aylward (1995) that the risk only relates to patients with undiagnosed (therefore untreated) angle closure glaucoma. The recommendation is to abandon the question about the presence of glaucoma and advise instead that patients should seek urgent medical advice should eye pain and visual loss develop. However, the authors did recommend caution in the presence of heart disease as this was considered of significant importance (Fink and Aylward, 1995).

The benefits and contraindications of Buscopan (from the Boehringer Ingelheim professional leaflet on 20 mg/1 ml solution ‘Buscopan’) and glucagon (from Novo Nordisk professional leaflet on glucagen 1 mg hypokit) are given in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 Hyascine butylbromide (Buscopan) versus glucagon (Glucagen)

| Hypotonic agent | Buscopan | Glucagen |

|---|---|---|

| Benefits | Good hypotonia achieved | Can be used in the presence of narrow angled glaucoma |

| Good colonic distension | ||

| Good active duration lasting for most of the examination | ||

| Significantly cheaper | ||

| Side effects | Temporary tachycardia | Can cause nausea |

| Blurred vision | Shorter acting | |

| Dizziness | Poorer colonic distension | |

| Drying of the mouth | ||

| Contraindications | Myasthenia gravis | Insulin dependent diabetes (glucagon has the opposite effect to insulin) |

| Megacolon | ||

| Narrow angle glaucoma | ||

| Tachycardia | ||

| Prostatic enlargement with urinary retention | ||

| GI stenosis or paralytic ileus | ||

| Poorly controlled angina | ||

| Relative contraindications | Elderly patient with a heart condition | |

| Pheochromocytoma | ||

| Insulinoma | ||

| Glucagonoma |

The double contrast barium enema

Good bowel preparation is an important precursor to a successful DCBE (see Chapter 3). Poor coating or residue can mask or mimic pathology and should be reported as such and an alternative strategy should be suggested (e.g. a limited repeat examination following further bowel preparation, to review those areas not well demonstrated).

The predominant difference in rectal tube types is related to whether or not they have a balloon cuff. There is limited advantage to having a cuff, as it can assist with contrast retention in a patient with poor sphincter control. However, significant complications can occur, such as perforation, following inadvertent cuff insufflation and barium infusion within the vagina due to incorrect tube placement. Colonic perforation following cuff insufflation in the rectum is associated with high, artificially induced, intraluminal pressure. It has been advised that balloon cuffs should be avoided (Blakeborough et al., 1997b; Chapman and Blakeborough, 1998; Culpan and Chapman, 2002).

The objective standard of all DCBE techniques should be the same:

Air or CO2 double contrast

Air or carbon dioxide (CO2) can be given to insufflate the bowel. Although practitioners need to be aware of the risks associated with over distension of the colon, if the bowel is collapsed in any view, consideration should be given to increasing gas input.

There are numerous papers discussing the benefits of air and CO2. CO2 dissolves faster and, although the mucosal coating is the same, the discomfort of CO2 is reported as less. However, air is considered to provide better distension and this might outweigh the advantages in patient acceptability that CO2 provides. Should colic result from air distension or should the effect of the chosen hypotonic agent wear off, maintaining rectal intubation will allow colonic decompression at any time but, particularly, as a routine at the end of the examination (Scullion et al., 1995, Holemans et al., 1998). One example of a DCBE protocol follows:

As imaging of the sigmoid colon has been completed, we are not worried at this point that the direction of the patient rotation has been aiding the passage of barium into and over the hepatic flexure. Turning the patient towards the left anterior oblique (LAO), the colon is screened both to make sure there is enough barium to demonstrate the right colon and to identify where barium is pooling in the region of the splenic flexure and descending colon. To remove the pooled barium in the left colon, the table is tilted head up (it is not normally necessary to stand the table erect both from the view point of patient comfort and to reduce the risk of them becoming hypotensive and possibly fainting (Roach et al., 2001)).

Table 13.2 Double contrast barium enema positioning and imaging

| Activity | Image | Example figure |

|---|---|---|

| Patient supine – inject hypotonic agent | ||

| Left lateral position – intubate | ||

| Turn patient prone | ||

| Infuse barium just over the splenic flexure | ||

| Turn patient to left then supine | ||

| Turn left – prone | ||

| Air insufflate, drain barium, air insufflate, turn patient onto left side: | ||

| Image 1: Turn towards left then prone |

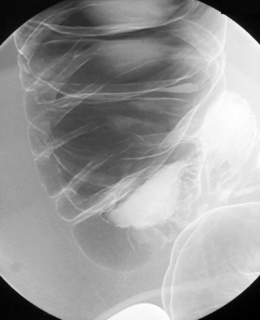

Right anterior oblique | Figure 13.1 |

| Image 2 | Prone | Figure 13.2 |

| Image 3 | Prone with caudal tube angulation | Figure 13.3 |

| Image 4 | Left posterior oblique | Figure 13.4 |

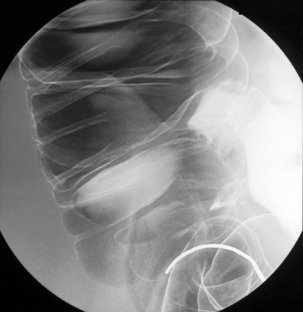

| Image 5 Check barium has reached right colon Drain barium from left side |

Left lateral | Figure 13.5 |

| Image 6 | Left anterior oblique of descending colon and splenic flexure | Figure 13.6 |

| Barium to cecal pole Image 7 Turn left then prone to coat medial and anterior wall of ascending colon while draining barium from right colon |

Supine transverse colon | Figure 13.7 |

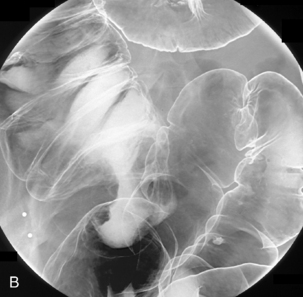

| Image 8 | Right lateral decubitus | Figure 13.8 |

| Image 9 | Right anterior oblique hepatic flexure | Figure 13.9 |

| Image 10 | Supine mid ascending (if needed) | Figure 13.10 |

| Image 11 | Supine and oblique of cecum with compression | Figure 13.11 |

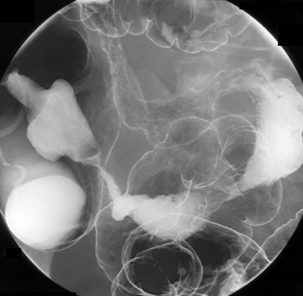

| Image 12 | Supine abdominal overview(s) | Figure 13.12 |

| Image 13 | Left lateral decubitus | Figure 13.13 |

Single contrast enema (SCE)

Historically, an SCE was undertaken on patients with large bowel obstruction that had not perforated to confirm the degree of obstruction and its location. These patients are now better served having a less invasive CT scan (Jacob et al., 2007).

However, the suggestion by Boardman and Nolan (1994) that there are occasions when an SCE examination can be employed is still true today despite the increasing use of CT. The SCE is still of value for patients who are referred for a DCBE but, due to infirmity and immobility, cannot lie prone or turn in a manner required to achieve a full DCBE examination. In these instances, infusing a dilute low density single contrast barium solution can still provide useful information. Following the injection of a hypotonic agent, the patient is turned onto their left side and the barium is infused as far as the hepatic flexure. Patient position and imaging can follow the flow of barium:

At this stage, rather than infusing more barium, draining the rectum and applying a few puffs of air will, in most instances, assist with the filling of the right colon.

Water-soluble contrast enema (Gastrografin enema)

The most common reason for performing a water-soluble contrast enema (WSEN) is as a postoperative check on the integrity and patency of anastomoses following anterior resection (Figure 13.16), total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis prior to reversing a defunctioning ileostomy (Dolinsky et al., 2007).

The standard barium enema tips should not be used as they are too rigid and could disrupt the surgical staples (see Figure 13.16). A soft tube such as the 16 Fg Jacques catheter is a safer option, inserting it only as far as it will freely pass. With low anterior resections in particular, over insertion is counter-productive as the contrast is required at the anastomotic margins. Patient positioning is aimed at putting contrast on the respective walls of the bowel (Table 13.3); however, prone imaging is to be avoided if at all possible due to patient discomfort that could be caused from the defunctioning stoma.

Table 13.3 Water-soluble contrast enema image projections to review anastomosis

| Activity | Function | Imaging of anastomosis |

|---|---|---|

| Left lateral position | Intubation with soft catheter | |

| Initial infusion of contrast | ||

| Image left lateral dependent wall | Left lateral | |

| Depending on stoma site, turn left and pronate as much as possible | Image left anterolateral wall | Left posterior oblique |

| Right anterior oblique | Image left posterolateral dependent wall | Right anterior oblique |

| Place supine | Image posterior dependent wall | Supine |

| Turn towards right | Image right posterolateral dependent wall | Left anterior oblique |

| Right lateral | Image right dependent wall | Right lateral |

| Depending on stoma site, pronate as much as possible | Image right anterolateral wall | Right posterior oblique |

Colostomy enema

The difficulty regarding a colostomy enema is the lack of a sphincter to retain the barium. A number of devices and techniques have been designed to allow barium infusion via a colostomy (Kushner et al., 1988; Williams and Scott, 2003).

Examination of the colon may be required following the formation of a colostomy (i.e. post anterior peroneal resection). To retain the barium, a 2 cm slit is made in the colostomy bag on the medial side of the stoma bag and a 10 Fg Law II tube inserted. Depending on the site of the stoma, it is possible to pass the tube over the splenic flexure without too much difficulty (Figures 13.17 and 13.18). Following the injection of a hypotonic agent with the patient lying on their right side, barium can be infused to fill the right colon. Should barium be ejected, it will be contained within the bag which, if needed, can be drained using a suction catheter. Turning the patient supine and then towards the left allows the barium to fill the transverse colon before being aspirated.

With the patient on their left side, air can now be infused through the tube. In the left lateral position the air will migrate to, and distend, the right colon (see Figure 13.18). Imaging starts in the right lateral position with the ascending colon. Images can then be taken as required as the patient is turned onto their back (Figure 13.19).

The patient experience

Subjectively, many patients are reticent about going to see their family doctor about symptoms associated with their ‘bottom’. In talking to the patient and explaining the procedure, it helps to be aware of the examination from their perspective and let them know you are aware. Many referred patients are of an age where comorbidities are likely to be a limiting factor and, in a number of cases, only by talking to the patient before the examination can this be properly assessed. The bowel preparation can leave the external anal margin feeling raw making intubation uncomfortable. Rectal intubation and the desire to evacuate is embarrassing and undignified. Careful control of the rate of barium infusion or gas insufflation can minimize the rectal discomfort.

Proctography

Defecation proctography provides dynamic imaging of the pelvic floor to assess the anatomy and dynamics of defecation (Hare et al., 2001). It can provide considerable weight to clinical decision making, such as whether surgery or conservative therapy would be more appropriate (Jones et al., 1998; Harvey et al., 1999).

Current defecation proctography methods range from utilizing rectal and small bowel contrast (Harvey et al., 1999) to what Kelvin and Maglinte (2001) and Altringer et al. (1995) describe as an extended examination incorporating bladder, small bowel, vaginal and rectal contrast. The standard examination described here can be performed and reported by a suitably trained radiographer.

Patients are predominantly female with symptoms of obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS) where individuals have difficulty in emptying their bowels. Symptoms of ODS often develop following injury during childbirth (Halligan, 2001). Proctography during pregnancy is contraindicated, not only because of the use of ionizing radiation, but also because the pregnancy and birth will have an effect on the pelvic floor, possibly altering the pelvic configuration and functionality (Halligan et al., 1996).

A number of alternative examinations complement defecating proctography (Dvorkin et al., 2005). These include:

Preparation specific to defecation proctography

The patient

Defecation proctography, by its very nature, is an embarrassing and undignified procedure that requires the trust and cooperation of the patient. Practitioner guidance on performing intimate examinations is provided by the Royal College of Radiologists (RCR, 1998).

To gain informed consent and the confidence of the patient, pre-examination time and privacy must be available to discuss the procedure. Reassurance must be given with respect to their dignity and emphasis made that maximum privacy will be assured during the examination (Kelvin and Maglinte, 2001). Any discussion at this stage must involve the patient’s symptoms including whether digitation or other patient-developed ‘methods’ to assist defecation are required on a regular basis. This allows for modifications of the standard procedure to be considered (Halligan et al., 1996).

The fluoroscopy room

The room used must provide complete privacy and have an en suite washroom facility. Patient privacy can be enhanced by using the distance between operator and subject provided by the remote control capability of a unit such as the Polystar Fluorospot unit with C-arm (Siemens), and by using a mobile lead screen beside the patient. Accessory equipment and contrast is prepared in advance of the session (Table 13.4). A specially adapted bedpan is placed so that it is readily available when required.

Table 13.4 Proctography: accessory equipment and contrast preparation

| Accessory equipment | Contrast | Preparation (per patient) |

|---|---|---|

Packet mash/potato starch

Proctography technique

One hour before imaging the patient drinks 100 ml Baritop diluted with 200 ml water. Ingested contrast will demonstrate the pelvic small bowel during the examination to identify a possible enterocele. The examination begins with the patient supine on the table and the technique as outlined in Box 13.1 is followed.

As well as small bowel contrast, rectal and vaginal contrast is also used (Kelvin and Maglinte, 2001) (Figure 13.20). The separate use of small bowel contrast once an enterocele had been indicated at defecating proctography has been reported in a study (Kelvin et al., 1992), however, it was recognized that this would increase the resultant dose of the examination.

Figure 13.20 Defecating proctogram: demonstrating cystocele, enterocele, sigmoidocele, rectocele and rectoanal intussusception.

Image by Helen Carter.

In assessing pelvic prolapse, vaginal contrast will demonstrate during evacuation any displacement of the bladder or widening of the rectovaginal space (Low et al., 1999). To minimize the risk of extravasation (Blakeborough et al., 1997a, Chapman and Blakeborough, 1998), only 2–3 ml of barium need be used to identify the vaginal apex and whether it has prolapsed below the pubococcygeal line.

Bladder contrast (Altringer et al., 1995; Kelvin and Maglinte, 2001) can be administered intravenously or by catheterization; however, it need not and should not be used in all cases, and risk/benefit considerations should be given before the administration of intravenous contrast agent (Bettmann, 2005; Namasivayam et al., 2006).

Delayed, post complete rectal evacuation images are recommended as enteroceles often only become evident at the end of evacuation. If not almost or fully empty, re-screen following attempted evacuation in the toilet for a further 5 minutes – an anismus may prevent herniation of the small bowel (Kelvin et al., 1999; Kelvin and Maglinte, 2001).

Aftercare

Information would include warning of the whitish colored motions for a couple of days and that if they find they get constipated to take a mild laxative.

Complications

Risks such as infection or urethral trauma are associated with bladder catheterization however brief (Wong and Hooton, 1981; Colley, 1998; Pratt et al., 2007).

Interpretation of images

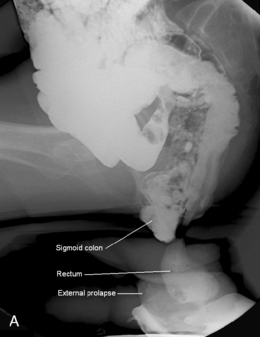

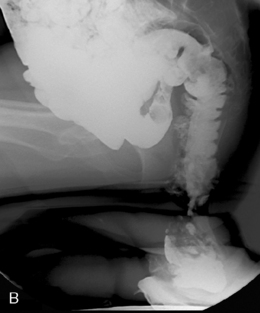

Interpretation of images considers the alterations in anorectal angle and position of anorectal junction in addition to the ability rapidly and completely to evacuate the contrast (Halligan, 2001). Prolapse of pelvic organs is considered in relation to the position of the pubococcygeal line and the extent of prolapse can be noted (Figures 13.21A, 13.21B).

BOX 13.1 Proctography technique and imaging

Right lateral position – images taken while resting, squeezing and straining; all of which must include the pubic symphysis and coccyx

Right lateral position – images taken while resting, squeezing and straining; all of which must include the pubic symphysis and coccyx Patient takes a seat while equipment changes to vertical position – specially adapted bedpan placed on footrest

Patient takes a seat while equipment changes to vertical position – specially adapted bedpan placed on footrest Right lateral position sat on bedpan – mobile screen positioned to provide some seclusion for patient

Right lateral position sat on bedpan – mobile screen positioned to provide some seclusion for patientAltringer W.E., Saclarides T.J., Dominguez J.M., Brubaker L.T., Smith C.S. Four-contrast defecography: pelvic ‘fluoroscopy. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1995;38:695-699.

Asao T., Kuwano H., Ide M., et al. Spasmolytic effect of peppermint oil in barium during double contrast barium enema compared with Buscopan. Clin. Radiol.. 2003;58(4):301-305.

Bettmann M.A. Contrast media: safety, viscosity, and volume. Eur. Radiol.. 2005;159(Suppl. 4):D62-D64.

Blakeborough A., Sheridan M.B., Chapman A.H. Complications of barium enema examinations: a survey of UK consultant radiologists 1992 to 1994. Clin. Radiol.. 1997;52(2):142-148.

Blakeborough A., Sheridan M.B., Chapman A.H. Retention balloon catheters and barium enemas: attitudes, current practice and relative safety in the UK. Clin. Radiol.. 1997;52(1):62-64.

Boardman P., Nolan D. Computer tomography of the colon in elderly people. (Letters) Single contrast barium study is adequate. Br. Med. J.. 1994;308(6944):1639.

Booth A.M., Mannion R.A.J. Radiographer and radiologist perception error in reporting double contrast barium enemas: a pilot study. Radiography. 2005;11:249-254.

Chapman A.H., Blakeborough A. Complications from inflation of a retention rectal balloon catheter in the vagina at barium enema. Clin. Radiol.. 1998;53(10):768-770.

Ciatto S., Castiglione G. Role of double-contrast barium enema in colorectal cancer screening based on faecal occult blood. Tumori. 2002;88(2):95-98.

Colley W. Female catheterisation. Nurs. Times. 1998;94(21):33A-133B.

Culpan D.G., Chapman A.H. Complications of radiographer performed double contrast barium enema examinations. Radiography. 2002;8(2):91-95.

Culpan D.G., Mitchell A.J., Hughes S., et al. Double contrast barium enema sensitivity: a comparison of studies by radiographers and radiologists. Clin. Radiol.. 2002;57(7):604-607.

de Freiter P.W., Soeters P.B., Dejong C.H. Rectal perforation after barium enema: a review. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2006;49(2):261-271.

Dolinsky D., Levine M.S., Rubesin S.E., et al. Utility of contrast enema for detecting anastomotic strictures after total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2007;189(1):25-29.

Dvorkin L.S., Hetzer F., Scott S.M., Williams N.S., Gedroyc W., Lunniss P.J. Open-magnet MR defaecography compared with evacuation proctography in the diagnosis and management of patients with rectal intussusception. Colorectal Dis.. 2003;6:45-53.

Dvorkin L.S., et al. Rectal intussusception in symptomatic patients is different from that in asymptomatic volunteers. Br. J. Surg.. 2005;92:866-872.

Elson E.M., Campbell D.M., Halligan S., et al. The effect of timing of intravenous muscle relaxant on the quality of double contrast barium enema. Clin. Radiol.. 2000;55(5):395-397.

Fink A.M., Aylward G.W. Buscopan and glaucoma: a survey of current practice. Clin. Radiol.. 1995;50(3):160-164.

Glick S.N. Colonoscopy versus barium enema: a reappraisal of the facts and issues. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1048-1053.

Goei R., Nix M., Kessels A.H., et al. Use of antispasmodic drugs in double contrast barium enema examination: glucagon or Buscopan? Clin. Radiol.. 1996;51(4):305.

Halligan S. Observer variation in the detection of colorectal neoplasia on double contrast barium enema: implications for colorectal cancer screening and training. Clin. Radiol.. 2004;59:762-776.

Halligan S. Introduction to functional pelvic floor imaging. Imaging. 2001;13:435-439.

Halligan S., Marshall M., Taylor S., et al. Observer variation in the detection of colorectal neoplasia on double contrast barium enema: implications for colorectal cancer screening and training. Clin. Radiol.. 2003;58:948-954.

Halligan S., Spence-Jones C., Kamm M.A., et al. Dynamic cystoproctography and physiological testing in women with urinary stress incontinence and urogenital prolapse. Clin. Radiol.. 1996;51:785-790.

Hare C., Halligan S., Bartram C.I., et al. Dose reduction in evacuation proctography. Eur. J. Radiol.. 2001;11:432-434.

Harvey C., Halligan S., Bartram C.I., et al. Evacuation proctography: a prospective study of diagnostic and therapeutic impact. Radiology. 1999;211:223-227.

Holemans J.A., Matson M.B., Hughes J.A., et al. A comparison of air, CO2 and an air/CO2 mixture as insufflation agents for double contrast barium enema. Eur. Radiol.. 1998;8(2):274-276.

Jacob S.E., Lee S.H., Hill J. The demise of the instant /unprepared contrast enema in large bowel obstruction. Colorectal Dis.. 2007. (on epub ahead of print)

Jones H.J., Swift R.I., Blake H. A prospective audit of the usefulness of evacuating proctography. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl.. 1998;80(1):40-45.

Kelvin F.M., Maglinte D.D.T. Extended proctography. Imaging. 2001;13:448-457.

Kelvin F.M., Hale D.S., Maglinte D.D.T., et al. Female pelvic organ prolapse: diagnostic contribution of dynamic cystoproctography and comparison with physical examination. Am. J. Roentgenol. 1999;173:31-37.

Kelvin F.M., Maglinte D.D.T., Horback J.A., et al. Pelvic prolapse: assessment with evacuation proctography (defecography). Radiology. 1992;184:547-551.

Klabunde C.N., Jones E., Brown M., et al. Colorectal cancer screening with double-contrast barium enema: a national survey of diagnostic radiologists. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2002;179:1419-1427.

Kushner D.C., Cleveland R.H., Herman T.E., et al. Retrograde colostomy and iliostomy enemas in neonates and infants: a simple combination of techniques. Gastrointest. Radiol.. 1988;13(2):180-182.

Law R.L., Slack N., Harvey R.F. An evaluation of a radiographer-led barium enema service in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Radiography. 2008;14(2):105-110.

Low V.H., Ho L.M., Freed K.S. Vaginal opacification during defecography: direction of vaginal migration aids in diagnosis of pelvic floor pathology. Abdom. Imaging. 1999;24(6):5665-6568.

Namasivayam S., Kalra M.K., Torres W.E., et al. Adverse reactions to intravenous iodinated contrast media: a primer for radiologists. Emerg. Radiol.. 2006;12:210-215.

Pratt R.J., Pellowe C.M., Wilson J.A. National evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. J. Hosp. Infect.. 2007;65(Suppl. 1):S1-S64.

Price R.C., le Masurier S.B. Longitudinal changes in extended roles in radiography: a new perspective. Radiography. 2007;13(1):18-29.

Quine M.A., Bell G.D., McCloy R.F., et al. Prospective audit of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in two regions of England: safety, staffing, and sedation methods. Gut. 1995;36(3):462-465.

Roach S.C., Martin D.J., Owen A., et al. Blood pressure changes during barium enema. Clin. Radiol.. 2001;56(5):393-396.

Roos J.E., Weishaupt D., Wildermuth S., et al. Experience of 4 years with open MR defecography: pictorial review of anorectal anatomy and disease. Radiographics. 2002;22:817-832.

Royal College of Radiologists. Intimate examination: guidance for members and fellows. London: Royal College of Radiologists, 1998.

Scullion D.A., Wetton C.W.N., Davies C., et al. The use of air or CO2 as insufflation agents for double contrast barium enema (DCBE): is there a qualitative difference? Clin. Radiol.. 1995;50(8):558-561.

Shorvon P.J. Commentary on: observer variation in the detection of colorectal neoplasia on double contrast barium enema: implications for colorectal cancer screening and training. Clin. Radiol.. 2003;58:945-947.

Teague R. Clinical practice guidelines update: safety and sedation during endoscopic procedures. British Society of Gastroenterology, 2003. Online: http://www.bsg.org.uk

Thompson W.M., Foster W.L., Paulson E.K., et al. Comparison of radiologist and technologists in the performance of air contrast barium enema. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2006;187:706-709.

Vora P., Chapman A. Complications from radiographer-performed double contrast barium enemas. Clin. Radiol.. 2004;59(4):364-368.

Williams J.T., Scott R.L. A new universal colostomy tip for barium enemas of the colon. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2003;180(5):1330-1331.

Winawer S.J., Fletcher R.H., Miller L., et al. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594-642.

Wong E.S., Hooton T.M. Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1981. [last modified 2005]. Available [online] at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/gl_catheter_assoc.html accessed on 17/11/2007

Dench J.E., Scott S.M., Luniss P.J., et al. External pelvic rectal suspension (the express procedure) for internal rectal prolapse, with or without concomitant rectocele repair: a video demonstration. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1922-1926.

Halligan S., et al. Predictive value of impaired evacuation at proctography in diagnosing anismus. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2001;177:633-636.

Jayne D.G., Finan P.J. Stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation and evidence-based practice. Br. J. Surg.. 2005;92:793-794.

Low V.H., Ho L.M., Freed K.S. Vaginal opacification during defecography: direction of vaginal migration aids in diagnosis of pelvic floor pathology. Abdom. Imaging. 1999;24(6):5665-6568.

Mahieu P., Pringot J., Bodart P. Defecography: I. Description of a new procedure and results in normal patients. Gastrointest. Radiol.. 1984;9(3):247-251.

Marshall M., Halligan S. Evacuation proctography. Imaging. 2001;13:440-447.

Persson P.B. Contrast-induced nephropathy. Eur. Radiol.. 2005;15(Suppl. 4):D65-D69.

Satsih S.C., Kimberly D., Welcher B.S., et al. Effects of biofeedback therapy on anorectal function in obstructive defecation. Dig. Dis. Sci.. 1997;42(11):2197-2205.

Stoker J., Halligan S., Bartram C.I. Pelvic floor imaging. Radiology. 2001;218:621-641.