Fluid and electrolyte balance

Concepts and vocabulary

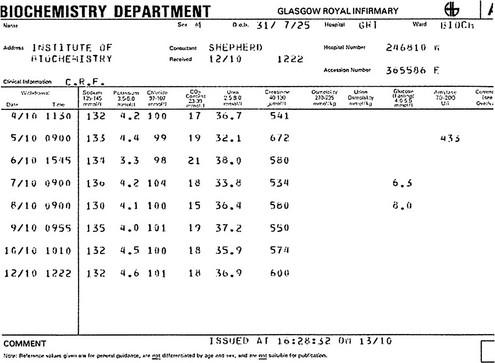

Fluid and electrolyte balance is central to the management of any patient who is seriously ill. Measurement of serum sodium, potassium, urea and creatinine, frequently with bicarbonate, is the most commonly requested biochemical profile and yields a great deal of information about a patient’s fluid and electrolyte status and renal function. A typical report is shown in Figure 6.1.

Fig 6.1 A cumulative report form showing electrolyte results in a patient with chronic renal failure.

Body fluid compartments

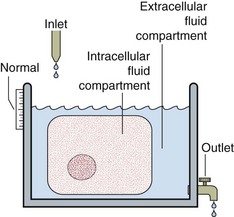

A schematic way of representing fluid balance is a water tank model that has a partition and an inlet and outlet (Fig 6.2). The inlet supply represents fluids taken orally or by intravenous infusion, while the outlet is normally the urinary tract. Insensible loss can be thought of as surface evaporation.

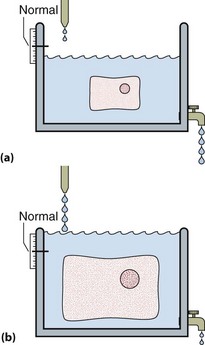

The water tank model illustrates the relative volumes of each of these compartments and can be used to help visualize some of the clinical disorders of fluid and electrolyte balance. It is important to realize that the assessment of the volume of body fluid compartments is not the undertaking of the biochemistry laboratory. The patient’s state of hydration, i.e. the volume of the body fluid compartments, is assessed on clinical grounds. The term ‘dehydration’ simply means that fluid loss has occurred from body compartments. Overhydration occurs when fluid accumulates in body compartments. Figure 6.3 illustrates dehydration and overhydration by reference to the water tank model. When interpreting electrolyte results it may be useful to construct this ‘biochemist’s picture’ to visualize what is wrong with the patient’s fluid balance and what needs to be done to correct it. The principal features of disordered hydration are shown in Table 6.1. Clinical assessments of skin turgor, eyeball tension and the mucous membranes are not always reliable. Ageing affects skin elasticity and the oral mucous membranes may appear dry in patients breathing through their mouths.

Table 6.1

The principal clinical features of severe hydration disorders

| Feature | Dehydration | Overhydration |

| Pulse | Increased | Normal |

| Blood pressure | Decreased | Normal or increased |

| Skin turgor | Decreased | Increased |

| Eyeballs | Soft/sunken | Normal |

| Mucous membranes | Dry | Normal |

| Urine output | Decreased | May be normal or decreased |

| Consciousness | Decreased | Decreased |

Electrolytes

A request for measurement of serum ‘electrolytes’ usually generates values for the concentration of sodium and potassium ions, together with bicarbonate ions. Sodium ions are present at the highest concentration and hence make the largest contribution to the total plasma osmolality (see later). Although potassium ion concentrations in the ECF are low compared with the high concentrations inside cells, changes in plasma concentrations are very important and may have life-threatening consequences (see pp. 22–23).

Urea and creatinine concentrations provide an indication of renal function, with increased concentrations indicating a decreased glomerular filtration rate (see pp. 28–29).

Concentration

Remember that a concentration is a ratio of two variables: the amount of solute (e.g. sodium), and the amount of water. A concentration can change because either or both variables have changed. For example, a sodium concentration of 140 mmol/L may become 130 mmol/L because the amount of sodium in the solution has fallen or because the amount of water has increased (see p. 6).

Osmolality

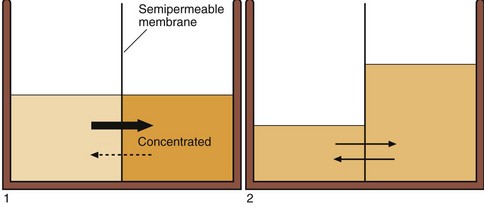

Body fluids vary greatly in their composition. However, while the concentration of substances may vary in the different body fluids, the overall number of solute particles, the osmolality, is identical. Body compartments are separated by semipermeable membranes through which water moves freely. Osmotic pressure must always be the same on both sides of a cell membrane, and water moves to keep the osmolality the same, even if this water movement causes cells to shrink or expand in volume (Fig 6.4). The osmolality of the ICF is normally the same as the ECF. The two compartments contain isotonic solutions.

Fig 6.4 Osmolality changes and water movement in body fluid compartments. The osmolality in different body compartments must be equal. This is achieved by the movement of water across semipermeable membranes in response to concentration changes.

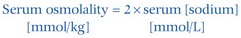

This simple formula only holds if the serum concentration of urea and glucose are within the reference intervals. If either or both are abnormally high, the concentration of either or both (in mmol/L) must be added in to give the calculated osmolality. Sometimes there is an apparent difference between the measured and calculated osmolality. This is known as the osmolal gap (p. 17).

Oncotic pressure

The barrier between the intravascular and interstitial compartments is the capillary membrane. Small molecules move freely through this membrane and are, therefore, not osmotically active across it. Plasma proteins, by contrast, do not and they exert a colloid osmotic pressure, known as oncotic pressure (the protein concentration of interstitial fluid is much less than blood). The balance of osmotic and hydrostatic forces across the capillary membrane may be disturbed if the plasma protein concentration changes significantly (see p. 50).