Problem 15 Flank pain in a 60-year-old man

Now that the patient’s condition has stabilized some further investigations can be considered.

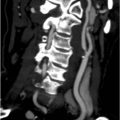

A non-contrast CT scan is performed and two representative slices are shown in Figure 15.1A, B.

He is readmitted 2 weeks later for a ureteroscopy after his urine is confirmed to be sterile.

Answers

A.8 A combination of anti-inflammatories and opioids is effective for renal colic.

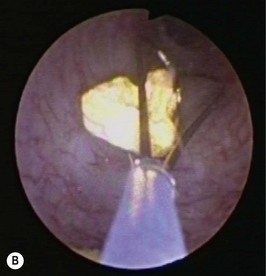

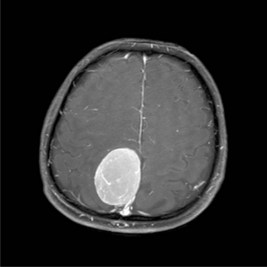

A.11 These are ureteroscopic photographs demonstrating Figure 15.1A after (1) the ureteric stone during LASER lithotripsy, and Figure 15.1B basket extraction of stone fragments.

Revision Points