Chapter 68 Flail Chest and Pulmonary Contusion

4 What is a flail chest, and how is it diagnosed?

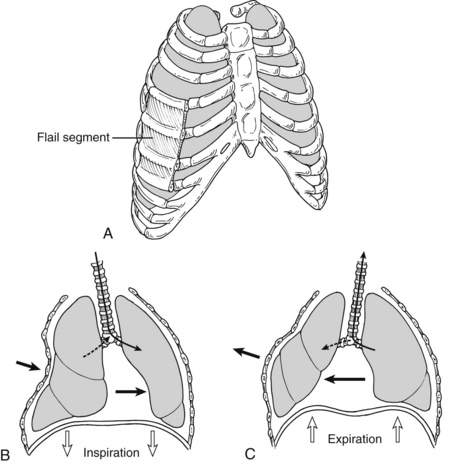

Flail chest is defined as fractures of three or more consecutive ribs or costal cartilages fractured in two or more places (Fig. 68-1). These fractured segments give rise to a free-floating portion of the thorax, which moves paradoxically throughout the respiratory cycle, with inward motion with inspiration and outward motion with exhalation. Although rib fractures may be diagnosed radiographically, flail chest is a clinical diagnosis. Patients often present with chest wall pain, tenderness, bruising, and palpable step-offs of the ribs, but flail chest is distinguished from other chest trauma by noting the paradoxical movement of the chest wall during spontaneous respiration. Patients receiving positive pressure ventilation usually do not demonstrate the classic paradoxical movements. Respiratory dysfunction usually does not arise from the paradoxical chest motion but rather is due to underlying contusions and splinting from pain.

6 What is the role of radiographs in the diagnosis of pulmonary contusion?

Pulmonary contusions are diagnosed radiographically. Although initial chest radiographs may be unremarkable, a nonsegmental infiltrate typically develops over a 6-hour period. If the contusions are visible on the initial chest radiograph, the injury is likely to be more severe, and enlargement of the contused area on the radiograph over the next 24 hours is a poor prognostic sign. Classic radiograph patterns include irregular consolidations or a diffuse patchy pattern (Fig. 68-2). Even after development of chest radiograph findings, plain radiographs may underestimate the severity of the contusions. CT scan is more sensitive for diagnosis of pulmonary contusions and can quantify the volume of lung involved.

8 What is the relationship between pulmonary contusions and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)?

9 What is the mortality rate and cause of death for patients with flail chest and pulmonary contusions?

11 What are the pitfalls in pain management of patients with blunt chest trauma without an endotracheal tube in place?

12 Does the type of pain control influence the rate of pneumonia in patients with multiple rib fractures?

14 Which respiratory therapy procedure(s) should be used for patients with significant blunt chest trauma?

17 What is the role of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) in the management of blunt chest trauma?

20 Are prophylactic antibiotics indicated in patients requiring a tube thoracostomy after chest trauma?

Key Points Flail chest and pulmonary contusion

1. Increasing age places patients with multiple rib fractures at high risk for pulmonary complications.

2. Pulmonary contusions place patients at increased risk for pneumonia and ARDS.

3. Management of flail chest or pulmonary contusion includes immediate assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation and, for stable patients, monitoring the respiratory status, pain control, lung physiotherapy, early mobilization, and adequate nutrition.

4. Fluid replacement for patients with pulmonary contusion should focus on ensuring adequate resuscitation to ensure end-organ perfusion followed by avoidance of further unnecessary fluid administration.

5. Lung protective strategies should be used when patients with a flail chest or pulmonary contusion require mechanical ventilation because of ARDS.

1 Al-Hassani A., Abdulrahman H., Afifi I., et al. Rib fracture patterns predict thoracic chest wall and abdominal solid organ injury. Am Surg. 2010;76:888–891.

2 Bastos R., Calhoon J.H., Baisden C.E. Flail chest and pulmonary contusion. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;20:39–45.

3 Battle C.E., Hutchings H., Evans P.A. Risk factors that predict mortality in patients with blunt chest wall trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury. 2012;43:8–17.

4 Bulger E.M., Edwards T., Klotz P., et al. Epidural analgesia improves outcome after multiple rib fractures. Surgery. 2004;136:426–430.

5 Carrier F.M., Turgeon A.F., Nicole P.C., et al. Effect of epidural analgesia in patients with traumatic rib fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Anesth. 2009;56:230–242.

6 Cohn S.M., DuBose J.J. Pulmonary contusion: an update on recent advances in clinical management. World J Surg. 2010;34:1959–1970.

7 Hernandez G., Fernandez R., Lopez-Reina P., et al. Noninvasive ventilation reduces intubation in chest trauma-related hypoxemia: a randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2010;137:74–80.

8 Kiraly L., Schreiber M. Management of the crushed chest. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(9 Suppl):S469–S477.

9 Kishikawa M., Yoshioka T., Shimazu T., et al. Pulmonary contusion causes long-term respiratory dysfunction with decreased functional residual capacity. J Trauma. 1991;31:1203–1208.

10 Livingston D.H., Richardson J.D. Pulmonary disability after severe blunt chest trauma. J Trauma. 1990;30:562–566.

11 Livingston D.H., Shogan B., John P., et al. CT diagnosis of rib fractures and the prediction of acute respiratory failure. J Trauma. 2008;64:905–911.

12 Nirula R., Mayberry J.C. Rib fracture fixation: controversies and technical challenges. Am Surg. 2010;76:793–802.

13 Sanabria A., Valdivieso E., Gomez G., et al. Prophylactic antibiotics in chest trauma: a meta-analysis of high-quality studies. World J Surg. 2006;30:1843–1847.

14 Simon B., Ebert J., Bokhari F., et al. Practice management guideline for “pulmonary contusion—flail chest” June 2006. Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, 2011. www.east.org Accessed April 15, 2011.

15 Tanaka H., Yukioka T., Yamaguti Y., et al. Surgical stabilization of internal pneumatic stabilization? A prospective randomized study of management of severe flail chest patients. J Trauma. 2002;52:727–732.