2. Five Element theory

Chapter contents

The Five Elements6

The Five Element resonances7

Five Element interrelationships8

The Organs or ‘Officials’11

The Law of Midday–Midnight12

The Five Elements

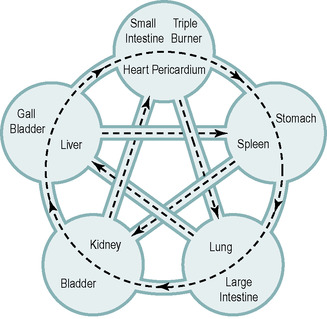

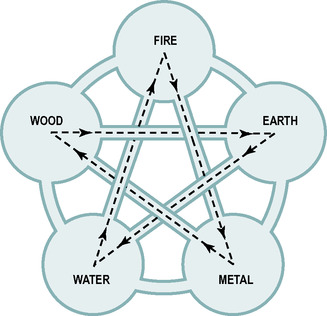

The idea that all of nature is governed by yin/yang and the Five Elements (Figure 2.1) lies at the heart of Chinese medicine. Zhu Yen (some time between −350 and −270) wrote extensively on the subject and the Five Elements are mentioned in both the Book of History and the Book of Rites (the dates for these are uncertain). The Ling Shu states that: ‘Nothing on earth or within the universe is unrelated to the Five Elements and Man is no exception’ (Ling Shu Chapter 64; quoted in Liu, 1988, p. 48).

|

| Figure 2.1 |

The Five Elements, which are Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal and Water, represent the fundamental qualities of all matter in the universe. The Chinese term for Element is xing. Xing means to walk or to move, and therefore the word ‘Element’ is somewhat misleading because it implies something more akin to a basic constituent of matter. For this reason, the translation ‘The Five Phases’ is often used. However, because the term ‘Element’ is so established, we continue to use it here, but the reader should be clear that an Element is a process, movement or quality of qi, not a fixed ‘building block’ (Rochat, 2009, p. 13; Kaptchuk, 2000, p. 437; Maciocia, 1989, p. 15; Needham, 1956, p. 244).

Each Element has its own particular quality of qi: ‘As soon as the Five Elements are formed, they have each their specific nature’ (Chou Tun-I; quoted in Needham, 1956, p. 461). One of the earliest texts describing the Five Elements outlined this emphasis on the different qualities of the Elements.

Water is that quality in Nature which we describe as soaking and descending. Fire which we describe as blazing and uprising. Wood which permits of curved surfaces or straight edges. Metal which can follow the form of a mould and then becomes hard. Earth which permits of sowing, growth and reaping.

(Shu Ching, –4th century; quoted in Needham, 1956, p. 243)

Above all, the Five Elements serve as a model for understanding the inexorable succession of the seasons. For many Daoists and Naturalists virtually no distinction was made between the nature of the seasons, the climate resonant with each season and the cyclical changes taking place in the human, animal and vegetable worlds. In plants the never-ending cycle of growth, flowering, harvest, decline and storing informed them of the differing qualities of each season. The behaviour of animals and humans in each season was also seen to be governed by the same laws.

Men have no choice but to go by this succession; officials have no choice but to operate according to these powers. For such are the calculations of heaven.

(Tung Chung-shu, –135; quoted in Needham, 1956, p. 249)

Over the course of history there have been several different models of Five Element theory, some coming from its application to agriculture or politics (see, for example, Cheng, 1987, pp. 18–22; Maciocia, 1989, pp. 15–35; Matsumoto and Birch, 1983, pp. 1–8). Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture is based on the model of the Five Elements set out in the Nei Jing and Nan Jing. This model, which envisages the Five Elements in a cyclical creative cycle, has always been the dominant one used by acupuncture practitioners.

Chinese medicine, like any system of medicine, is predominantly concerned with understanding and alleviating physical and psychological suffering. The writers of the medical classics strove to understand how the Five Elements affected people and how physicians could observe this. The ‘resonances’ associated with each Element are how the condition of the Elements inside the person is revealed to the practitioner. ‘Associations’ or ‘correspondences’ are the usual words used in this context, but these words imply a relationship between separate entities. We have chosen to use the word ‘resonances’ as it implies an underlying sameness.

The Five Element resonances

When people’s qi becomes either deficient (xu) or full (shi) within an Element, changes start to take place in various aspects of the physical body as well as in the mind and spirit. (This idea is present in both the Nei Jing and the Nan Jing, but is put most succinctly in Nan Jing, Chapter 16.)

The practitioner diagnoses the dysfunction by perceiving disharmony in patients’ odour, voice tone, facial colour and in the external expression of their inner state. It is not that the imbalanced qi ‘causes’ the changes to happen, but that the odour, colour, tone and emotion ‘resonate’ (ying) in harmony with the condition of the qi of the Element (see Birch and Felt, 1998, p. 93, for a description of how ‘resonance’ is a more understandable concept to the Chinese than to Westerners).

The Ling Shu states: ‘Between Heaven and Earth, the number five is indispensable. Man also resonates with it’ (Yang and Chace, 1994, p. 54). This concept of ‘resonance’, exemplified by sympathetic vibrations in gongs across a temple hall, was vital to early Chinese ideas concerning science and medicine (Needham, 1956, pp. 282–283). Indeed, ‘The fundamental idea of the Book of Changes (I Jing) can be expressed in one word – resonance’ (Shih Shuo Hsu Yu; quoted in Needham, 1956, p. 304).

The quality of qi resonant with the Wood Element in Heaven manifests as the season of spring, the climatic qi of wind and in a person as the emotion of anger. Humanity stands between Heaven and Earth and the Five Elements are present within us just as they are present throughout all the manifestations of the Dao.

According to Su Wen there are Five Elements in the sky and Five Elements on the earth. The qi of earth, when in the sky, is moisture. … the qi of wood, when in the sky, is wind.

(Shen Kua; quoted in Needham, 1956, p. 267)

There have been many resonances attributed to the Elements over the centuries, many not in a medical context. Table 2.1 sets out the resonances commonly used by practitioners of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture (these resonances are often referred to in the classics, but Nan JingChapter 34 is devoted to this topic). They are the resonances that most clearly give us an understanding of how the Five Elements manifest in people. It is easy to say that the Wood Element plays the same role in people’s character as the spring plays in the annual cycle of the seasons. It requires considerable experience and depth of understanding, however, to be able to make an accurate diagnosis based on observation of how these resonances manifest in people. For example, when the Water Element is out of balance then a putrid odour, an imbalance in the person’s ability to deal effectively with fear, a groan in the voice tone and a blue facial colour also arise. Cultivating the ability to diagnose from such signs is one of the main challenges for the Five Element Constitutional Acupuncturist.

| Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | green | red | yellow | white | blue |

| Sound | shouting | laughing | singing | weeping | groaning |

| Emotion | anger | joy | sympathy/worry | grief | fear |

| Odour | rancid | scorched | fragrant | rotten | putrid |

| Season | spring | summer | late summer | autumn/fall | winter |

| Climate | wind | heat | humidity | dryness | cold |

| Taste | sour | bitter | sweet | pungent | salty |

| Power | growth | maturity | harvest | decrease | storage |

Human emotions in particular are seen as being equivalent to the different forms of qi present throughout Nature. Often they are the most overt manifestations of the Element that can be discerned in the person.

Just as there are wind and rain in Heaven, so there are joy and anger in man.

(Ling Shu, Chapter 71; Lu, 1972)

Heaven has four seasons and five Elements or phases to engender (sheng), make grow (zhang), gather (shou) and store (cang), to produce cold, heat, dryness, dampness and wind. Man has five zang (Organs) and, through transformation, five qi to produce elation (xi), anger (nu), sadness (bei), grief (you) and fear (kong).

(Su Wen, Chapter 5; Larre and Rochat de la Vallée, 1996, p. 27)

If practitioners understand, for example, how winter is the period of storing (cang) and of holding reserves during a phase of little discernible activity, they can gain a great deal of understanding into the role the Water Element plays in a person. Observing and understanding the different qualities of qi in each season enables the practitioner to diagnose patients according to the balance of the Five Elements within them. Understanding the difference between the qi of spring and the qi of summer or how the qi of dampness is different from the qi of cold, informs the practitioner of the difference between the Elements in a person.

Five Element interrelationships

The other key concept in Five Element theory and the practice of Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture is the interrelationships between the Elements, a concept that featured particularly in the Nan Jing. This great classic of Chinese medicine has been the most influential text in the development of Japanese and Five Element acupuncture (see Unschuld, 1986, p. 3). Focusing on issues of interrelationships and interdependence is a typically Oriental way of looking at things. Many Western students and practitioners of acupuncture find this less easy. They are more inclined to focus on the ‘things’ relating rather than on the relationships themselves. The translation of ‘Element’ rather than ‘phase’ or ‘process’ colludes with this way of thinking.

Oriental concepts of gardening, feng shui, cuisine, and many other aspects of life place much of their focus on the relationships between objects rather than on the object itself. Confucianism stresses the importance of maintaining a ‘proper’ relationship between the individuals in a family or society. It regards these relationships as crucial to the proper functioning of society and to the person’s own well-being. In Chinese communities an individual’s psychological problems are usually seen as being problems in relation to other individuals, especially other family members. The concepts of yin/yang and the Five Elements are based on an exploration and an understanding of relationships.

This emphasis on relationships means that establishing balance and harmony between the Five Elements is crucially important in this style of acupuncture. The goal of the practitioner is to achieve equilibrium between all the Elements. In the Ling Shu it says: ‘The principles of needling dictate that needling should stop as soon as qi is brought into harmony’ (Lu, 1972, Chapter 9).

It is important to reinforce or reduce the qi of an Element if it leads to greater harmony between that Element and other Elements. If a person is deficient in qi but the Elements are in relative harmony, then this may lead to a lack of well-being but it is unlikely to cause a serious disorder. If, on the other hand, there is a large discrepancy between the qi of different Elements, then this can cause more severe physical or psychological symptoms. This view is summed up in the Nei Jing.

It is necessary to promote the flow of qi and blood according to the laws of mutual victories among the Five Elements in order to strike a balance among them and bring about peace.

(Su Wen, Chapter 74; Lu, 1972)

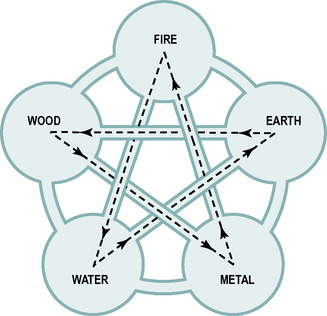

The most important relationships between the Five Elements are those controlled by the sheng and ke cycles.

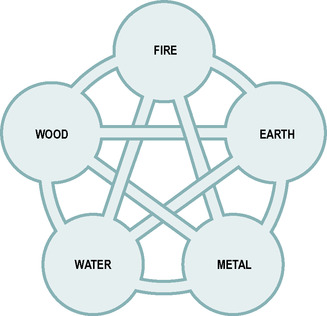

The sheng cycle

The transition of the seasons provides the most obvious model for this cycle of the Elements. Just as summer follows spring and winter follows autumn, so the seasons ‘generate’ each other according to the sheng cycle, as illustrated in Figure 2.2. The character for sheng (Weiger, 1965, lesson 79F) is shown below.

|

| Figure 2.2 |

|

The Daoist Liu I Ming described the sheng cycle like this:

When yin and yang divide, the Five Elements become disordered (luan). The Five Elements, Metal, Water, Wood, Fire, and Earth, represent the five qi. The Five Elements of early heaven create each other following the sheng cycle. These Five Elements fuse to form a unified qi.

(translation by Jarret, 1998; based on Cleary, 1986b, p. 66)

Just as the qi of Heaven in the form of the seasons are seen to follow each other, the qi of Earth is also seen to follow the same cycle. This is described by practitioners of Chinese medicine in the following way:

• Wood creates Fire by burning.

• Fire creates Earth from ashes.

• Earth creates Metal by hardening. (Metal in this context is synonymous with rock or ore found within the Earth.)

• Metal creates Water by containment. 1

• Water creates Wood by nourishment.

Mother–child relationship

The sheng cycle is of the utmost importance in Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture as it is fundamental to the idea that a practitioner can generate change in the organs of one Element by treating another Element. Chapter 69 of the Nan Jing discusses the sheng cycle in terms of the relationship between a mother and child. If the ‘child’ Element is deficient, then it may be because it is not receiving sufficient qi from its ‘mother’. It may be more effective to treat the ‘mother’ to engender more qi in the ‘child’ Element than treating the child itself. For example, if the Fire Element is deficient the practitioner may reinforce the Wood Element in order to provide qi for the Fire Element (by analogy, throwing more wood on the fire in order to generate more flames). This kind of connection fitted into contemporary thinking during the Han dynasty.

There is an unvarying dependence of the sons on the fathers and a direction from the fathers to the sons. Such is the Dao of Heaven.

(Tung Chung-shu, –135; quoted in Needham, 1956, p. 249)

Five Element theory also mentions that if a ‘child’ Element becomes too full (shi) it can deleteriously affect the ‘mother’ Element. For example, if the Wood Element is too full then it may have ‘robbed’ the Water Element, which becomes depleted. This relationship is known as ‘zi dao mu qi’ or ‘the son steals the mother’s qi’.

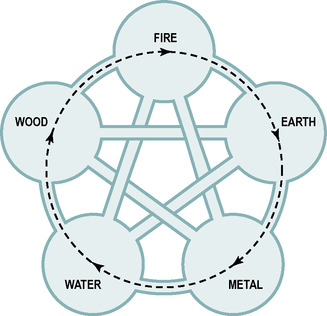

The ke cycle

|

The Chinese character for ke shown here is taken from Weiger (1965), lessons 29A and 75K. The ke, or ‘control’, cycle describes a relationship between the Elements which is less apparent from nature than the sheng cycle. Focusing on interrelationships, the writers of the Nei Jing and Nan Jing observed pathological effects on the Element two stages along the sheng cycle.

In the mystery of nature, neither promotion of growth (sheng) nor control (ke) is dispensable. Without promotion of growth, there would be no development; without control, excessive growth would result in harm.

(Ling Shu; Liu, 1988, p. 53)

The ke cycle is illustrated in Figure 2.3. It is described in the following way:

|

| Figure 2.3 |

The cycle of control maintains unity within the Five Elements. As the Ling Shu says, ‘Without control, excessive growth would result in harm.’ If an Element starts to become dysfunctional, however, it may easily lose ‘control’ or it may ‘over-act’ on the Element it controls across the ke cycle. (When the ke cycle becomes pathological, it is called the ‘contempt’ cycle.) For example, if the Organs of the Wood Element struggle, the Organs of the Earth Element will often start to show signs of distress.

The elements ‘insulting’ each other

The sheng cycle is the most important relationship of the Elements in that deficiency in one Element easily leads to a secondary deficiency or excess in the ‘child’ Element. The ke cycle, however, tends to produce more complex interrelationships.

Being excessive, qi not only acts on what it should, but also counteracts on what it should not. Being insufficient, qi is not only overacted on by what acts upon it, but is also counteracted upon by what it should act upon.

(Treatise on the Five Circuit Phases in Su Wen; Liu, 1988, p. 56)

This means that if the organs of an Element are out of balance they may ‘insult’ the organs of the Element that should be controlling it (see Figure 2.4). For example, if the Liver suffers it may produce imbalance in the Lungs.

|

| Figure 2.4 |

Treating the constitutional imbalance

Any Element can be adversely affected along the sheng and/or ke cycles by imbalance in any other Element (see Scheid, 1988, for a discussion of these relationships). In clinical practice practitioners see complex pictures of imbalance that make it hard to be sure by which route one Element has been affected by another. The key lies in understanding which Element was the first to become imbalanced. The practitioner focuses much of the treatment on this Element and thereby affects other Elements that have become imbalanced. This enables the practitioner to generate improvement in the person’s qi by treating at the root of the person’s disharmony.

The Organs or ‘Officials’

The twelve organs have been associated with particular Elements from the time of the Nei Jing (see Figure 2.5). As well as teaching the more commonly accepted functions of the Organs, Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture places particular emphasis on Chapter 8 of Su Wen (see Larre and Rochat de la Vallée, 1992, for a detailed and thought-provoking commentary on Su WenChapter 8). This chapter describes the twelve organs as though they were ‘officials’ in a court, each with a particular ministry or role. This way of thinking about the Organs is similar to a Daoist concept, prevalent at that time, that people are composed of several different ‘deities’ who reside within them. For example, the Ling Hsien, written by Chang Heng (+7 to +139), describes the various gods sitting around in heaven, each of them occupying the position of an official in a court.

Su Wen, Chapter 8, portrays the Organs more in terms of their functions in a person’s mind and spirit than of their functions in the physiology of the body.

The Officials and their ‘ministries’ are as follows (Larre and Rochat de la Vallée, 1992, pp. 151–152):

• The Heart holds the office of lord and sovereign. The radiance of the spirit stems from it.

• The Lung holds the office of minister and chancellor. The regulation of the life-giving network stems from it.

• The Liver holds the office of general of the armed forces. Assessment of circumstances and conception of plans stem from it.

• The Gall Bladder is responsible for what is just and exact. Determination and decision stem from it.

• Tan zhong (an early name for the Pericardium) has the charge of resident as well as envoy. Elation and joy stem from it.

• The Stomach and Spleen are responsible for storehouses and granaries. The five tastes stem from them.

• The Large Intestine is responsible for transit. The residue from transformation stems from it.

• The Small Intestine is responsible for receiving and making things thrive. Transformed substances stem from it.

• The Kidneys are responsible for the creation of power. Skill and ability stem from them.

• The Triple Burner is responsible for opening up passages and irrigation. The regulation of fluids stems from it.

• The Bladder is responsible for regions and cities. It stores the body fluids. The transformations of the qi then give out their power.

Placing importance on these functions diagnostically is unique in contemporary practice (as far as the authors are aware) to Five Element Constitutional Acupuncture. Awareness of the ‘Officials’ leads to a practitioner emphasising modes of behaviour and ways of thinking when diagnosing patients. This focus supersedes any indications arising from the physical symptoms (see Chapters 3, 4 and the chapters on the Elements, this volume, for discussion of the priority given to diagnosis based on the person’s psychological characteristics).

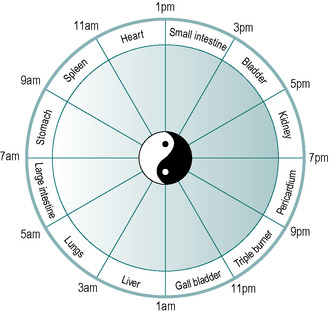

The Law of Midday–Midnight

Each Official has a 2-hour period in the day when its qi is stronger (Figure 2.6). This concept is an ancient one. It comes from the school of biorhythmic methodology known as zi wu liu zhu fa and goes back to at least the Tang dynasty (+618 to +906) (Soulié de Morant, 1994, p. 121, claims it goes back to −104 in the Han dynasty but gives no reference). There is also a period of time (roughly 12 hours from the strongest time) when the Organ is at its weakest.

|

| Figure 2.6 |

In practice it can give useful diagnostic information about the condition of an Organ. Patients, for example, often report that they find it hard to sleep during the strongest time of day for the Liver (1–3 a.m.) and then find it especially hard to stay awake after lunch (1–3 p.m.).

In treatment, the horary points can be used to tonify an Organ at its strongest time (see Section 6, this volume). The relevance of the time of day and how this is used diagnostically is discussed for each Organ in Section 2.

Summary

1 The qi of each Element is different in its nature. Season, climatic factors and human emotions are all variations of the Elements.

2 When one of a person’s Five Elements becomes out of balance, the ‘resonances’ of that Element manifest themselves.

3 Diagnostically the most important resonances are the facial colour, voice tone, emotion and odour.

4 The Five Elements are bound by a complex system of interrelationships. This means that each Element is affected by changes taking place in another Element.

5 Balance and harmony between the Elements is of prime importance.

6 Emphasis is placed on the descriptions of the Organs as ‘Officials’ given in Su Wen, Chapter 8.

7 Each Official has a 2-hour period in the day when its qi is stronger.