Chapter 1 First Encounter with a Patient

Examination and Formulation

Examination

The examination, which overall remains irreplaceable in diagnosis, consists of a functional neuroanatomy demonstration: mental status, cranial nerves, motor system, reflexes, sensation, and cerebellar system, and gait (Box 1-1). This format should be followed during every examination. Until it is memorized, a copy should be taken to the patient’s bedside to serve both as a reminder and as a place to record neurologic findings.

The examination usually starts with an assessment of the mental status because it is the most important neurologic function, and impairments may preclude an accurate assessment of the other neurologic functions. The examiner should consider specific intellectual deficits, such as language impairment (see Aphasia, Chapter 8), as well as general intellectual decline (see Dementia, Chapter 7). Tests of cranial nerves may reveal malfunction of nerves either individually or in groups, such as the ocular motility nerves (III, IV, and VI) and the cerebellopontine angle nerves (V, VII, and VIII) (see Chapter 4).

In contrast to DTRs, pathologic reflexes are not normally elicitable beyond infancy. If found, they are a sign of CNS damage. The most widely recognized pathologic reflex is the famous Babinski sign. Current medical conversations justify a clarification of the terminology regarding this sign. After plantar stimulation, the great toe normally moves downward (i.e., it has a flexor response). With brain or spinal cord damage, plantar stimulation typically causes the great toe to move upward (i.e., to have an extensor response). This reflex extensor movement, which is a manifestation of CNS damage, is the Babinski sign (see Fig. 19-3). It and other signs may be “present” or “elicited” but they are never “positive” or “negative.” Just as a traffic stop sign may be either present or absent, but never positive or negative, a Babinski sign is present, elicited, or found.

Frontal release signs, which are other pathologic reflexes, reflect frontal lobe injury. They are helpful in indicating an “organic” basis for a change in personality. In addition, to a limited degree, they are associated with intellectual impairment (see Chapter 7).

Physicians evaluate cerebellar function by observing several standard maneuvers that include the finger-to-nose test and rapid repetition of alternating movement test (see Chapter 2) for intention tremor and incoordination. If at all possible, physicians should watch the patient walk because a normal gait requires intact CNS and PNS motor pathways, coordination, proprioception, and balance. Moreover, all these systems must be well integrated.

Examining the gait is probably the single most valuable assessment of the motor aspects of the nervous system. Physicians should watch not only for cerebellar-based incoordination (ataxia), but also for hemiparesis and other signs of corticospinal tract dysfunction, involuntary movement disorders, apraxia (see Table 2-1), and even orthopedic conditions. In addition, physicians will find that certain cognitive impairments are associated with particular patterns of gait impairments. Whatever its pattern, gait impairment is not merely a neurologic or orthopedic sign, but a condition that routinely leads to fatal falls and permanent incapacity for numerous elderly people each year.

Formulation

Although somewhat ritualistic, a succinct and cogent formulation remains the basis of neurologic problem solving. The classic formulation consists of an appraisal of the four aspects of the examination: symptoms, signs, localization, and differential diagnosis. The clinician might also have to support a conclusion that neurologic disease is present or, equally important, absent. For this step, psychogenic signs must be separated, if only tentatively, from neurologic (“organic”) ones. Evidence must be demonstrable for a psychogenic or neurologic etiology while acknowledging that neither is a diagnosis of exclusion. Of course, as if to confuse the situation, patients often manifest grossly exaggerated symptoms of a neurologic illness (see Chapter 3).

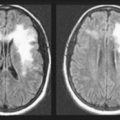

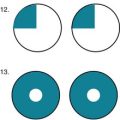

Localization of neurologic lesions requires the clinician to determine at least whether the illness affects the CNS, PNS, or muscles (see Chapters 2 through 6). Precise localization of lesions within these regions of the nervous system is possible and generally expected. The physician must also establish whether the illness affects the nervous system diffusely or in a discrete area. The site and extent of neurologic damage generally indicate certain diseases. A readily apparent example is that cerebrovascular accidents (strokes) and tumors generally involve a discrete area of the brain, but Alzheimer disease usually causes widespread, symmetric changes.

To review, the physician should present a formulation that answers the four questions of neurology: