2 Fillers

evolution, regression, and the future

Summary and Key Features

• The first pre-modern era filler was fat

• The first commercial modern era US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved filler was bovine collagen

• The first non-commercial modern era non-FDA approved filler was silicone

• Collagen was offered in 0.5 mL and 1 mL syringes for correction of ‘two-dimensional’ problems, i.e. wrinkles, scars

• Collagen had two major problems: delayed hypersensitivity and brief duration

• The introduction of botulinum toxin eliminated dynamic movement as a cause of wrinkles and lines, and allowed true volume deficits to be appreciated

• The introduction of hyaluronic acid (HA) gel fillers from Europe was a game changer, initially because of duration of effect; other benefits were seen later

• With HAs, attention shifted from ‘two-dimensional’ to ‘three-dimensional’ problems, i.e. from lines and wrinkles to subcutaneous atrophy and fat loss

• Fillers that followed, e.g. polylactic acid, calcium hydroxylapatite, polymethylmethacrylate, focused more on host response and endogenous collagen production than true volume replacement, mimicking the phenomenon seen with micro-droplet silicone

• Almost all fillers in the foreseeable future are entering the USA from Europe

• Newer fillers seek ability to control length of duration, enhanced stimulation of dermal collagen, reversibility, and greater lift

Collagen (Zyderm®, Zyplast®, Cosmoderm®, Cosmoplast®, Evolence®)

Collagen is the most abundant protein in skin. Collagen implant material was first developed by four Stanford doctors in the early 1970s: Rodney Perkins, John Daniels, Edward Lock, and Terrence Knap. In 1977, they reported the successful injection of human-, rabbit-, and rat-derived collagen into subcutaneous tissue of rats. This successful experiment led them to try injecting the scars and depressions of volunteers with both human- and bovine-derived collagen. These volunteers had a 50–85% improvement that was sustained over 3–18 months. Following extensive clinical trials in the late 1970s, Zyderm®1 implant (35 mg/mL of solubilized collagen) was approved by the US Food and Drug administration in 1981 (Fig. 2.1A), and Zyderm®2 (65 mg/mL of solubilized collagen) was approved in 1983. Both products were a relatively non-viscous suspension that allowed for injection through a 30-gauge needle. Because 2–3% of treated patients developed localized allergic reactions associated with these injections, pre-treatment skin testing with 0.1 mL subcutaneous challenges was recommended prior to using the Zyderm® 1 and 2 implants.

All forms of injectable bovine collagen were mildly immunogenic. The threat of bovine spongiform encephalopathy from prion disease mandated the use of closed herds as the only suitable source of solubilized collagen. Non-bovine collagen sources were developed from human tissue culture lines, which eliminated the allergic reactions seen with the bovine products. Cosmoderm® and Cosmoplast® (Fig. 2.1B) had very different flow characteristics than Zyderm® and Zyplast® and lacked the allergic profile of bovine collagen, but their very limited duration of effect (generally 3–4 months) and the desire to move away from protein-based fillers led to their abandonment by the marketplace once the hyaluronic acid (HA) gels arrived on the scene. But for 18 years, from 1981 to 2003 when Restylane® was approved by the FDA, collagen was the only commercially available FDA-approved product in the US market. The only other product that was in use during that period was silicone, and it had a more checkered history to be reviewed later. The true expansion of the commercially available fillers in the US market came instead with the introduction of the HA gels.

Hyaluronic acids (Restylane®, Perlane®, Juvéderm® Ultra, and Ultra Plus)

After years of use outside the USA, Restylane® (Q-med, Uppsala, Sweden) became the first HA to enter the US market with FDA approval on 12 December 2003, 9 months after the FDA approval of the Cosmoderm® human collagen implants (see www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices). This was a watershed event that marked the end of 17 years of domination of the US filler market by the collagen products. Restylane® (Fig. 2.2A) has an HA concentration of 20 mg/mL with a gel bead size of 250 µmol and 100 000 units per mL; there is an estimated 0.5–1.0% cross-linking with butanediol diglycidyl ether. Perlane® (Q-med, Uppsala, Sweden) contains 20 mg/mL of HA with a larger gel bead size of 1000 µmol and 10 000 units per mL, and less than 1% cross-linking. Perlane® is positioned as a more robust HA filler in the Q-med line.

The ephemeral nature of some fillers in the US market can be illustrated by the fate of Hylaform® (Inamed, Santa Barbara, CA), which the FDA approved in April 2004. Hylaform® had 5.5 mg/mL of HA and 20% cross-linking with divinyl sulfone. Hylaform Plus® (Inamed, Santa Barbara, CA), approved on 13 October 2004, had 5.5 mg/mL, larger gel particle size, and 20% cross-linking. Both products were HA gels derived from rooster cockscombs; they were withdrawn because of the market’s desire to move away from animal-sourced products and the lack of duration of effect of the less concentrated Hylaform®. In addition Inamed, the manufacturer of Hylaform®, was acquired by Allergan in 2006. By this acquisition Allergan obtained distribution rights to the competing HA filler, Juvéderm® (Fig. 2.2B), which is manufactured by Corneal Laboratories (Pringy, France). Juvéderm® is a homogeneous rather than particular form of HA gel and has become the leading product in the US market. Allergan then completed its purchase of Corneal in January 2007, leaving no further purpose for Hylaform® in the Allergan portfolio.

Silicone

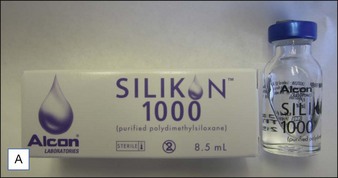

Silikon 1000® (Fig. 2.3A) is a silicone oil with a viscosity of 1000 centistokes. It was approved for use in postoperative retinal tamponade during vitreoretinal surgery. Under the FDA’s modernization act of 1997, the so-called ‘off-label’ use of approved products and devices by licensed physicians is recognized as a legitimate process by which the scope and practice of medicine are enlarged and expanded. Many dermatologists use Silikon 1000® ‘off label’ for the treatment of acne scars, HIV lipodystrophy, traumatic fat atrophy, rhinoplasty defects, and some facial aging where volume repair gives an effective result. Illegal use of adulterated industrial grade silicone fluids by laypersons continues to produce sensational adverse reactions including deaths – a reality that has colored the public’s perception of this valuable tissue augmentation agent. Illegal use of non-medical-grade product, together with the controversy surrounding silicone breast implants fanned by FDA Commissioner David Kessler MD in 1992 when he called for a ban on silicone implants, meant that silicone has remained in the background as a filler for some time. The lack of interest of commercial sponsorship of necessary long-term safety studies virtually guarantees it will remain an ‘off-label’ use for the foreseeable future.

Poly-L-lactic acid (Sculptra®)

The FDA accepted ‘non-inferiority’ comparative trials to evaluate the fillers that came after collagen. Perhaps as a result of these clinical trial designs, manufacturers continued to present the marketplace with single syringes of approximately 1.0 mL in volume. However, the HIV epidemic created a compelling need for volume restoration because of the pan-facial atrophy associated with HIV / AIDS and protease inhibitor therapies. The FDA approved poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA) (Dermik, Laboratories, Berwyn, PA) in August 2004 for the correction of facial atrophy secondary to HIV and therapy for AIDS. Off-label use for areas such as the nasolabial folds began almost immediately. The FDA then granted a second approval for treatment of nasolabial folds and facial wrinkles to the sponsor, Sanofi-Aventis US, in August 2009, and it is marketed as Sculptra® (Fig. 2.3B). PLLA is a filler with durations reportedly of as much as 18–24 months. Treament requires that the filler be prepared in advance using sterile preserved water and that the patient come in for a series of three injections over the course of several months. The PLLA material is thought to stimulate fibroblasts in the host to produce collagen. The volume of PLLA injected in any one session usually approaches 5–10 mL. Although PLLA continues to have its advocates, the initial failure to appreciate the need for dilution prior to use, lack of reversibility, and dependence on multiple treatments to achieve results have limited wider utilization of the product. The desire to achieve ‘permanent’ results has spurred the introduction of other products that promise, and occasionally deliver, the possibility of longer durations – among them fillers that contain particles that resist biological degradation, such as calcium hydroxylapatite and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA).

Calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse®)

Calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse®, now owned by Merz Aesthetics, formerly BioForm Medical, WI) was FDA approved on 22 December 2006 for the augmentation of moderate to severe facial lines and folds and for facial soft tissue loss from HIV-related lipoatrophy (Fig. 2.3C). It consists of 30% concentration of 25–45 µm calcium hydroxylapatite spherical particles suspended in sodium carboxymethylcellulose gel. It lasts approximately 1 year or more in most patients. It is inherently biocompatible because it is identical in composition to bone material. Off-label use has included volume restoration for dorsal hands and post-rhinoplasty contour correction. Lack of immediate reversibility and contraindication for use in the lips limit applicability to some extent, but the product has a steady niche market.

Polymethylmethacrylate (Artefill®)

PMMA is composed of non-resorbable PMMA 20% and 80% bovine collagen and was FDA approved as Artefill® (Fig. 2.3D) in October 2006 (Artes Medical, San Diego, CA) following earlier European use as Artecoll® dating from 1998. Following corporate upheaval involving the original management under the founder, Gottfried Lemperle, the product was purchased out of bankruptcy in 2009 by Cowen Healthcare Royalty Partners and reorganized as Suneva Medical. Artefill® is a chemically inert and biocompatible synthetic implant used in bone and dental implants. Skin allergy pre-screening tests are needed owing to bovine collagen content. The body degrades the collagen carrier within 1–3 months. The PMMA microspheres are non-biodegradable and their persistence is extremely long lasting to permanent. The use of PMMA is appropriate for patients with well-defined deep facial wrinkle lines. Granulomas appear to be less common with the current product, down to 0.01% range, but sensitivity to the bovine collagen component and the animal derivation of the collagen remain issues. Clinical trials for acne scarring are reportedly under way following reports (e.g. by Epstein & Spencer) of utility in this indication.

Conclusion

The list of filler products that are commercially available outside of the USA is protean. While admittedly many of these are refinements of existing technologies (better cross-linking, different particle size, combined with anesthetic, etc.), many are new classes of products that are different from those currently available in the USA (Fig. 2.4), e.g. polyacrylamide gels, cross-linked dextran, carboxymethylcellulose, hypromellose, etc. There are over 200 commercial products outside the USA. But we would predict that we shall see fillers moving beyond the traditional concept of inert medical devices into the realm of true biologicals: materials that will improve the texture, elasticity, radiance, and possibly color, of the skin itself. Just as the last 40 years has been the movement from two to three dimensions, the next two decades will see movement from the macro- to the microlevel and fillers will become systems for active metabolic manipulation and protection of the aging skin. The challenge for us as clinicians will be to sort through the hype and be able to choose the products that will offer the balance of risk and benefit. Given the preternatural attraction of the public for the newest and the greatest, we will have our work cut out for us.

Barnett JG, Barnett CR. Treatment of acne scars with liquid silicone injections: 30-year perspective. Dermatologic Surgery. 2005;31(11 pt 2):1542–1549.

Epstein RE, Spencer JM. Correction of atrophic scars with Artefill: an open-label pilot study. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2010;9(9):1062–1064.

Fischer G. First surgical treatment for modelling the body’s cellulite with three 5-mm incisions. Bulletin of the International Academy of Cosmetic Surgery. 1976;2:35–37.

Fournier PF. Facial recontouring with fat grafting. Dermatology Clinics. 1990;8(3):523–537.

Fournier PF, Otteni FM. Lipodissection in body sculpturing: the dry procedure. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1983;72(5):598–609.

Illouz YG. Body contouring by lipolysis: a 5-year experience with over 3000 cases. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1983;72(5):591–597.

Kessler D. Statement on silicone gel breast implants. [cited 11 November 2011]. Online. Available http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Speeches/ucm106949.htm, 1992.

Klein AW. Implantation technics for injectable collagen. Two and one-half years of personal clinical experience. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1983;9(2):224–228.

Knapp TR, Kaplan EN, Daniels JR. Injectable collagen for soft tissue augmentation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 1977;60(3):398–405.

Kupper T. Suneva giving wrinkle filler another try [cited 2 November 2011]. Online. Available http://www.signonsandiego.com/news/2009/nov/08/smoother-sailing/?page=1, 2009. – article

Selmanowitz VJ, Orentreich N. Medical-grade fluid silicone. A monographic review. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1977;3(6):597–611.

Stegman SJ, Tromovitch TA. Implantation of collagen for depressed scars. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1980;6(6):450–453.

Stegman SJ, Tromovitch TA, Glogau RG. Cosmetic dermatologic surgery. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1984.

Stegman SJ, Tromovitch TA, Glogau RG. Cosmetic dermatologic surgery, 2nd edn. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1990.

Tromovitch TA, Stegman SJ, Glogau RG. Zyderm collagen: implantation technics. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1984;10(2 pt 1):273–278.

Van de Graaf RC, Korteweg SF. Gustav Adolf Neuber (1850-1932) and the first report on fat auto-grafting in humans in 1893. Journal of the History of Plastic Surgery and Related Specialties. 2010;1:7–11.

Zappi E, Barnett JG, Zappi M, et al. The long-term host response to liquid silicone injected during soft tissue augmentation procedures: a microscopic appraisal. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33(suppl 2):S186–S192. discussion S192