106 Fibrosing alveolitis

Salient features

Examination

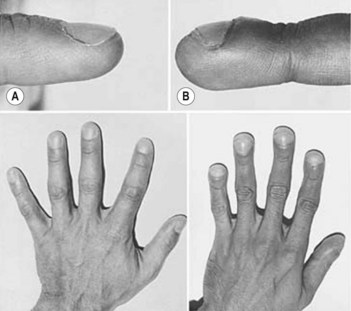

• Clubbing (Fig. 106.1; see also Case 218)

• Bilateral, basal, fine, end-inspiratory crackles that disappear or become quieter on leaning forwards. Furthermore, the crackles do not disappear on coughing (unlike those of pulmonary oedema). The crackles have been called ‘velcro’ or ‘cellophane’ crackles

Advanced-level questions

Mention possible aetiological factors

Metal dust (steel, brass, lead), wood dust (pine), wood smoke and smoking.

Mention other conditions which have similar pulmonary changes

What are the types of interstitial pneumonitis?

Liebow and Carrington in 1969 described five subgroups depending on histology.

Classical (usual) interstitial pneumonia (UIP). This is characterized by thickening of the alveolar interstitium by fibrous tissue and mononuclear cells; characteristically varying in severity from one focus to another. The mean survival is 2.8–5.6 years; 12% respond to steroids and spontaneous improvement does not occur.

Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP). There is a marked accumulation of macrophages in the alveolar airspaces associated with a relatively mild but uniform thickening of the interstitial space caused by mononuclear inflammatory cells. The mean survival is 12.4–14 years. The response to steroids is 62% and spontaneous improvement is 22%.

Non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). The survival is 14 years and therapeutic response is similar to DIP. This is a a diffuse lesion similar to UIP but with superimposed bronchiolitis obliterans.

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP). There is marked infiltration of interstitium by lymphocytes that may be indistinguishable from lymphoma.

Giant-cell interstitial pneumonia. Consists of a mononuclear cell infiltrate in the interstitium associated with large numbers of multinucleated giant cells.

How would you investigate this patient?

• Chest radiography: typically shows small lung volumes and bilateral basal reticulonodular shadows, which progress upwards as the disease progresses. In advanced disease, there is marked destruction of the parenchyma, causing ‘honeycombing’ (caused by groups of closely set ring shadows), and nodular shadows are not conspicuous. The mediastinum may appear broad as a result of a decrease in lung volume.

• Blood gases: arterial desaturation worsens while upright and improves on recumbency. There is arterial hypoxaemia and hypocapnia.

• Pulmonary function tests: in the early stages lung volumes may be normal, but there is arterial desaturation following exercise. Typically there is a restrictive defect with reduction of both the gas transfer factor and gas transfer coefficient.

• Blood tests: high ESR, raised immunoglobulins, raised anti-nuclear factor and rheumatoid factor positive.

• Bronchial lavage: a large number of lymphocytes indicates a good response to steroids and a good prognosis. A large number of neutrophils and eosinophils indicates a poor prognosis (5-year survival rate of 60% for steroid responders versus 25% for non-responders). The patients are more likely to respond to cyclophosphamide if the number of neutrophils is increased (Am Rev Respir Dis 1987;135:26).

• Lung biopsy: in early stages there is mononuclear cell infiltration in the alveolar walls, progressing to interstitial fibrosis (UIP); in later stages, fibrotic contraction of the lung, honeycombing, bronchial dilatation and cysts are seen. The DIP form, with alveolar macrophages and little mononuclear infiltration or fibrosis, has a better prognosis than UIP as it responds to steroids.

• MRI: useful in determining disease activity without ionizing radiation but it is an expensive method.

• High-resolution CT: useful to assess the pattern and extent of disease. A heterogeneous distribution of patchy, peripheral reticular densities, broad bands of fibrosis and honeycombing are typical features seen on high-resolution CT. Patients with a predominantly ground-glass appearance in the lungs are treated whereas those with a predominantly reticular appearance undergo technetium diethylenetriamine pentaacetate scanning (DPTA) to assess the probability of deterioration. It may avoid the need for biopsy especially if predominantly reticular shadowing. It acts as a guide for ideal biopsy site.

• DPTA scanning in non-smokers is of value in identifying which patients are more likely to deteriorate. Therapy can be postponed when there is slow clearance, whereas those with fast clearance should receive treatment (Eur Respir J 1993;6:797–802).

How would you manage this patient?

• Approximately 30% of patients treated with prednisone have had objective evidence of improvement. Therefore, all patients should be considered for a course of steroids (unless there are contraindications): prednisolone 40 mg/day for 6 weeks. Monitor symptoms and do a chest radiography and lung function tests. If response is good, continue; if no response then taper over 1 week.

• Steroid non-responders may benefit from a course of cyclophosphamide. Occasionally, patients who are unresponsive to prednisolone and cyclophosphamide will respond to prednisolone and azathioprine. Colchicine, penicillamine, interferon-gamma-1b and pirfenidone have also been used alone or as corticosteroid-sparing drugs. No well-controlled, randomized, and blinded studies have shown any of these medications to be efficacious

• High dose of acetylcysteine, administered over a period of 1 year, in addition to prednisone and azathioprine preserves vital capacity and diffusing capacity of the lung in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis better than standard therapy alone. The administration of acetylcysteine has no effect on survival.

Mention some genetic disorders with pulmonary fibrosis

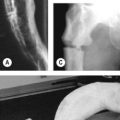

• Dyskeratosis congenital: pulmonary fibrosis is present in 20% of patients. Dyskeratosis congenita is also typically associated with a triad of mucocutaneous manifestations: skin hyperpigmentation (p. 400), oral leukoplakia (p. 637) and nail dystrophy (p. 673)

• Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome: oculocutaneous albinism, a bleeding diathesis and pulmonary fibrosis.