Chapter 16 Fibromyalgia

With contribution from Dr Lily Tomas and Greg de Jong

Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a functional condition typified by widespread muscle and joint pain affecting at least 2% of the general population1 and as high as 15%.2 While the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria consists of the identification of at least 11 of 18 standardised tender points, a range of symptoms also exists including fatigue, insomnia and mood disorders (anxiety and depression).3 Furthermore, demonstrated affects on cognitive function (‘fibrofog’) have been confirmed with demonstrated influences on memory and attention.4, 5 Indeed, fibromyalgia is considered a functional somatic syndrome2 rather than a disease, in that it is a diagnosis of exclusion concluded only after other musculoskeletal disorders have been ruled out.6

Significantly, fibromyalgia is frequently found to exist contemporaneously with other functional somatic syndromes.7 Two studies of the relationship between fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) identified that IBS existed in 77%8 and 70%9 of fibromyalgia patients (compared to controls in which 18% and 10% had IBS). Of patients with fibromyalgia, 70% were also found to meet the criteria of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS); 10 33 of 60 (55%) with fibromyalgia were considered to meet the criteria of multiple chemical sensitivity.11 As a result it has been suggested that these conditions may represent different symptoms and expressions of common pathogenetic mechanisms due to their substantial overlap,8 such that specific diagnosis between functional somatic syndromes may depend considerably upon the pragmatics of the assessment rather than definitive pathology.7

Due to the debilitating nature of fibromyalgia, long-term consequences and only partial effectiveness of pharmaceutical medicines to alleviate the symptoms, let alone affect a ‘cure’, many patients explore complementary and alternative medicines (CAM). In fact a study of patients presenting to a tertiary clinic identified that 96% of patients with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia had used CAM in the prior 6 months.12 Of the most frequently used CAM therapies, 48% used exercise, 45% spiritual healing, 44% massage, 37% chiropractic, and 20% weight loss programmes.12

Organic factors

Genetic factors

Family studies of fibromyalgia patients demonstrate that the condition aggregates in families. Furthermore it is possible that mood disorders and fibromyalgia may share inherited factors.13 Inheritability appears to be of a polymorphic nature with evidence of influence amongst serotoninergic, dopaminergic and catecholaminergic systems.14, 15, 16 Furthermore it has been postulated that subgroups of fibromyalgia patients exist with genetic factors likened to the differentiation of immune cells.17 Thus emerging evidence suggests that the individual existence, variance and degree of fibromyalgia may be influenced by heterogenous genetic influences.

Muscle changes

Fibromyalgia patients demonstrate definitive muscle changes according to pathology testing. DNA fragmentation has been noted, with disorganisation of actin and myofibre filaments and accumulation of glycogen and lipids within tissues. Muscles appear ‘moth eaten’, however inflammatory changes are not noted.18 One possible explanation for such changes is vasomotor dysregulation and vasoconstriction in muscles with a resulting low level ischemia leading to metabolic consequences.19 Muscle performance and electromyography has demonstrated an inability to relax during work activity as significant in fibromyalgia patients.20 Muscle strength has also been found to be 35% less per unit.21

Results regarding muscle energy metabolism are mixed. In some instances no difference has been found between fibromyalgia patients and controls during rest, exercise or recovery according to measures of phosphocreatine, inorganic phosphate and intracellular pH.22 However, measures of pyruvate, lactate, adenosine triphosphate and muscular isoenzymes of lacticodeshydrogenase have been found to be altered suggesting biochemical abnormalities during glycolysis may exist.23 Histological studies may also indicate abnormalities of the mitochondria, reduced capillary circulation and endothelial thickness may lead to oxygen debt, impaired oxidative phosphorylation and reduced ATP synthesis.24 Mitochondrial numbers have also been found to be significantly lowered,25 however in other instances a slight increase in type 1 muscle fibres have been noted, with type II muscle fibre atrophy.26

Oxidative stress and nutrient deficiencies

Fibromyalgia patients also appear to be under oxidative stress as identified by a comparison of oxidative stress parameters with myalgic scores and associated depression.27 Total antioxidant capacity has been observed to be significantly lower and total peroxide levels higher in fibromyalgia patients when compared to normals. A significant negative correlation between total antioxidant capacity and visual analogue scale for pain was also noted.28 These findings are consistent with investigations of female fibromyalgia patients that identified increased free radical parameters and decreased antioxidant parameters (Superoxide Dismutase) leading to oxidant/antioxidant imbalances as compared to normals.28 Hence it has been hypothesised that oxidative stress and nitric oxide balance may play an important role in fibromyalgia.30

Coenzyme Q10 is both an important aspect of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and anti-oxidant and has also been found to be abnormally distributed in patients with fibromyalgia, increased reactive oxygen species being identified in mononuclear cells of fibromyalgia patients, but decreased in the presence of CoQ10.31 Vitamin A and E have been found to be significantly reduced but not Vitamin C and beta–carotene in a study that also identified raised lipid perioxidation in patients with fibromyalgia.32

Vitamin D

In a small study of 40 female fibromyalgia patients, 17 demonstrated 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations less than 20nmol/l as compared to 7 normals.33 In a cross-sectional study of 150 patients with non-specific musculoskeletal pain, ages ranging between 10 and 65, 28% demonstrated severe Vitamin D deficiency (<20nmol), 55% of whom were younger than 30 years. Young women and immigrants had the highest levels of deficiency, however the authors emphasised that risks extended beyond patients traditionally suspected of Vitamin D deficiency (aged, housebound, immigrant).34 Low Vitamin D levels have also been noted amongst rheumatology patients in general35 and associated with fibromyalgia patients presenting with associated anxiety and depression.36

Calcium/magnesium

Preliminary studies comparing ATP, calcium and magnesium platelet levels in fibromyalgia patients were indicative of a trend towards higher calcium concentrations and significant elevations in magnesium simultaneous with lower ATP platelet levels suggesting that abnormal calcium–magnesium flow regulation may be of relevance in fibromyalgia.37 Intracellular evaluations demonstrate similar calcium–magnesium flow abnormalities exist with a possible influence on muscle contractility in fibromyalgia patients.

Amino acid/neurotransmitter balance

It has been hypothesised that an altered tryptophan metabolism may be responsible for fibromyalgia, however investigations suggest this may only be present in a subgroup of patients.38 A study of plasma levels of amino acids indicated that patients with fibromyalgia have significantly decreased levels of the branch chain amino acids; valine, leucine and isoleucine, and phenylalanine than normals, but no difference in measures related to tryptophan uptake or serotonergic markers.39 However, in contrast a second study indicated multiple individual amino acids (taurine, alanine, tyrosine, valine, methionine, phenylalanine and threonine) and the sum total of amino acids competing with tryptophan for brain uptake were found to be lower in fibromyalgia patients, suggesting gut protein malabsorption may be indicated with subsequent potential influences on neurotransmitter balance.40

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis indicated that in patients with fibromyalgia with other overlapping conditions (as compared to normals and primary fibromyalgia), pain intensity and tender point index co-varied with concentrations of metabolites of the excitatory neurotransmitters, glutamate and asparagines, with glycine and taurine also showing covariance with tender point index measures.41 Arginine, a precursor to nitric oxide, co-varied with tender point index scores for both primary and fibromyalgia associated with other conditions. The authors concluded that an increase in excitatory amino acid release may be associated with increased nitric oxide synthesis eventually leading to increase pain in fibromyalgia patients.41

Central nervous system (CNS)

A 2008 review of literature concluded that recent studies of fibromyalgia highlight abnormalities in the CNS processing of pain leading to increased sensitivity and a lowered threshold for pain. Persistent nociceptive input may lead to plastic changes provoking central sensitisation and chronic pain states. The authors suggested that these central changes were indicative of many of the syndromes that overlap with fibromyalgia, such as IBS, low back pain, migraine and temporomandibular disorders.42

It has also been suggested that autonomic nervous system dysregulation may exist in some patients as exemplified by the common finding of postural orthostatic tachycardia.43 However, the autonomic response in fibromyalgia patients to stress tasks appears to differ within subgroups. Although patients with fibromyalgia consistently demonstrated reduced surface electromyographic (EMG) readings at baseline, subsets of fibromyalgia patients present with increased sympathetic vasomotor reactivity and reduced muscular response with or without increased sudomotor reactivity during stress tasks, while others demonstrated parasympathetic vasomotor reactivity, reduced sudomotor activity and reduced muscular response. These variant autonomous system responses to stress subsequently imply that heterogenous groups of fibromyalgia exist.44 Abnormal responses of the sympathetic nervous system may be related to exaggerated norepinephrine (noradrenaline release) that have been observed amongst female patients with fibromyalgia.45

Cortisol

A review of papers in 2001 found that in one-third of studies, cortisol at baseline was significantly low in one-third of patients while 24-hour urinary cortisol levels are frequently within the lower part of normal.46, 47 Cortisol responses to increased ACTH in stress, exercise and during hypoglycaemic events are often blunted48, 49, 50 suggestive of an impaired ability to activate the hypothalamic pituitary portion of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis with subsequent adrenal hypo-responsiveness leading to a relative adrenal insufficiency.47–52 A lower expression of corticosteroid receptors has also been observed which may be compounded by lower levels of anti-inflammatory mediators.53

Consistent with this clinical studies have revealed that cortisol levels at waking and 1 hour after waking have a relationship to morning pain scores in women with fibromyalgia, although this relationship does not appear relevant later in the day.54 In the late evening an elevation of cortisol levels was evident in half of all fibromyalgia patients compared to normals and tending towards being statistically lower overnight, again suggesting a loss of resilience in the basal circadian function of the HPA axis.55

Thyroid hormone

Autoimmune thyroid disease (ATD) has been identified in a subgroup of patients presenting with fibromyalgia. An examination of 56 patients with a diagnosis of ATD identified 31% could be classified as having fibromyalgia.56 A study of thyroid antibodies in 128 fibromyalgia patients demonstrated that thyroid autoimmunity existed in 34% of fibromyalgia patients as compared to 18.8% of normals, with the highest frequencies in those patients with previous psychiatric treatment, postmenopausal women and patients presenting with a frequent history of dry mouth.57 In a further study, 41% of fibromyalgia patients had thyroid antibodies despite normal basal ranges, however age and depression were not found to be significant. Frequent symptoms reported in this study included dry eyes, burning/pain with urination, allodynia, blurred vision and a sore throat.58 There is a 4.5 times calculated likelihood of detecting thyroid antibodies associated with fibromyalgia.59

Growth hormone

A physiological dysregulation of the HPA also appears to be a factor in impaired growth hormone secretion (rather than production) frequently reported in patients with fibromyalgia.60, 61 Growth hormone stimulation tests often demonstrate blunted responses suggesting the possibility of hypothalamic origin for growth hormone dysfunction.62

Sleep, melatonin and the immune system

Fibromyalgia patients commonly report early morning awakenings, feeling tired, lack of sleep, cognitive disturbances and on occasion, sleep apnoea. Poor sleep quality has been noted to parallel pain intensity. Fibromyalgia patients often demonstrate sleep abnormalities consistent with normals during sleep deprivation (alpha-delta sleep anomaly), increased stage 1, decreased delta sleep and an increase in the number of sleep arousals.63 Dysfunctional beliefs regarding sleep may also play a role in fibromyalgia.64

Melatonin is important in regulating wake–sleep cycles. Fibromyalgia sufferers appear to have significantly lower levels of melatonin than normal controls. In a study comparing total melatonin secreted between 1800hr and 0800hr and hours of darkness (2300hr to 700hr) fibromyalgia patients were observed to be 31% lower in the latter measure and peak serum levels of melatonin were also considerably lower. It was concluded that these variations in melatonin may lead to the impaired night sleep, day fatigue and altered perceptions of pain associated with fibromyalgia pain.65

Elevations in cytokine levels have also been implicated in sleep–wake dysregulation in fibromyalgia patients. These immune mediators form a link between the periphery and the neuroendocrine, autonomic, limbic and cortical areas of the CNS and have hence been found to mediate sleep, sleepiness and fatigue.66, 67 However, views and evidence appear varied on the input of the immune system and whether it is in an excited or inhibited state. While some papers suggest there is no evidence that fibromyalgia is associated with a heightened immune system response, indeed immunosuppression may be a significant factor, trials with immunotherapies risk inducing fibromyalgia like symptoms.67 Results of C-reactive protein (CRP) studies, however, have indicated raised CRP levels are often present in patients with fibromyalgia.69

Infections

Consistent with findings of immune system involvement is the preliminary evidence that viral and other infections may be present in patients with fibromyalgia. Indeed a review of tender points during acute viral infection indicates that tender points are common and transient features during acute illness.70 Patients with acute episodes of fibromyalgia have been demonstrated to have an increase in IgM antibodies to enterovirus as compared to both chronic fibromyalgia and normal controls, suggesting a variance in their immune response.71 Of fibromyalgia patients, 13% who had muscle biopsies were found to have enterovirus present within their muscle tissue. Persistence of infection was suspected as an influence on fibromyalgia by the reporters due to these associated biopsy findings.72

A study of the presence of mycoplasmal infections in patients with chronic fatigue and/or fibromyalgia indicated that single or multiple mycoplasma organism infections (fermentans, pneumonia, hominis, penetrans) were present in over 50% of these individuals. Infections with mycoplasmal species were consistent with longer symptoms of fibromyalgia.73 Furthermore, it has been hypothesised that mycoplasmal infection may be a significant factor in thyroid abnormalities noted to occur in some fibromyalgia patients.74

A statistical association also appears to exist between Human T Cell Lymphotropic Virus Type 1 infections and patients with fibromyalgia — 38% of patients with this infection experiencing fibromyalgia as compared to 3% of normals.75 There does not appear to be a relationship between fibromyalgia and either hepatitis C (HCV) or human parvovirus B19.76, 77

Lifestyle factors

Psychological

Studies of psychological and psychosocial influences on, and comorbidities with, fibromyalgia also suggest that it is not a homogenous syndrome, with mixed elements individual to each patient being significant dependent upon their psychosocial background.80 For example, a degree of somatization appears to be a significant predictive factor in the development of fibromyalgia. A prospective study of 1658 adult patients demonstrated that patients who developed widespread pain often had a prior tendency towards somatisation.81

A comparison of psychological factors of fibromyalgia when compared to rheumatoid arthritis amongst patients attending a tertiary clinic indicated a high percentage of fibromyalgia patients. Ninety percent (N = 36) had a prior psychiatric diagnosis as compared to less than 50% for rheumatoid arthritis.82 However, while the presence of anxiety and depression are common and may exist in definable subgroups, it has been shown that the degree of the psychological comorbidities of anxiety and depression varies between patients with a subgroup of patients (‘adaptive copers’) demonstrating very few comorbidities at all.80

Psychosocial

A cross-sectional study of the community observed that people with fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain reported more health impairments than people with no pain, or regionalised pain. There was also an increased incidence of fibromyalgia amongst people of low socioeconomic status, low educational levels, low social support and a family history of chronic pain,83 and amongst employed women and housewives.

Stress

Stress-related issues also appear to be pertinent. Indeed, fibromyalgia patients commonly demonstrate clinically significant levels of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)-like syndromes,84 while registering greater levels of significant disability (85% vs 50%). Those fibromyalgia patients with PTSD-like symptoms reported significantly greater levels of pain, emotional distress, life interference and disability as compared to fibromyalgia patients without PTSD symptoms. Only 15% of fibromyalgia patients with PTSD syndromes were considered adaptive copers as compared to 48% without symptoms.

Consistent with this, fibromyalgia patients appear to be associated with higher levels of victimisation than other patients (control group consisted of rheumatoid arthritis patients and other rheumatology patients).85, 86 Forms of victimisation included abuse of a sexual, physical or emotional basis (neglect);87 in particular, adult physical abuse, although childhood abuse was also significant. A further study suggested this relationship (without reaching clinical significance), however, did determine with significance that frequency of abuse was a correlate with fibromyalgia,88 even if this relationship has not always been demonstrated for all forms of abuse.89 Links have also been determined with frequency of drug abuse.88 Work stress, including workplace bullying (almost 4 times as likely), high workload (twice as likely) and low decision latitude also appear pertinent associated related/causal factors.90

Tobacco

People who smoke appear to have higher pain intensities, numbness, severity and functional difficulties than non-smokers with fibromyalgia, however, no significant difference has been associated with number of tender points or fatigue levels.91, 92 Psychiatric therapy use and alcohol consumption were higher in fibromyalgia patients who smoked as was the level of un-restorative sleepiness and anxiety-depression.93 Smokers experienced fewer good days and more days of work missed per week.92

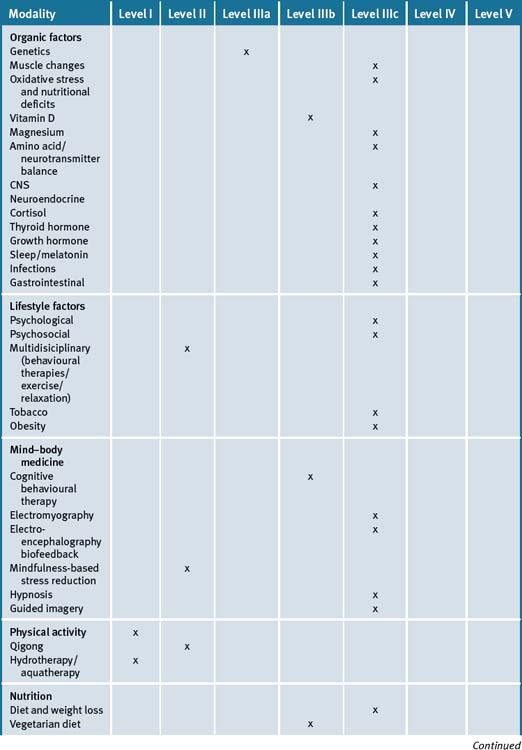

Overview of treatment evidence for fibromyalgia

A review of the multi-factorial causation and associations with fibromyalgia identifies why it is a difficult condition to treat. As a heterogenetic syndrome with multiple overlaps with other functional syndromes and conditions (IBS, chronic fatigue, mood disorders etc.) it is essential that both a multi-disciplinary yet individualised approach is undertaken for each patient with fibromyalgia. This may also explain why many treatment approaches have only a low level of evidence, given that evidential support for treatment methods that might only be successful in particular subsets of patients would be statistically blunted if applied to undifferentiated groups of fibromyalgia patients. This further infers that comprehensive assessment is essential when addressing the patient with fibromyalgia in order to establish which therapy amongst the many advocated for the condition is both pertinent and a priority to the individual.

Multidisciplinary treatment approaches

Given the multi-factorial nature of fibromyalgia, it is unsurprising that multidisciplinary programmes are often applied to fibromyalgia patients. However, while some individual studies have demonstrated improvements from multidisciplinary approaches (group behavioural therapies, stress management, relaxation plus exercise),96–99 a Cochrane review (2000) found there was little evidence that such programmes were of benefit, given the poor quality of existing studies.100 However, subsequent clinical trials continue to indicate the potential of multidisciplinary programmes101 with growing evidence to their efficacy when combinations of behavioural therapies, exercise, relaxation and other such sessions are included.102, 103

Mind–body medicine

A study of 28 fibromyalgia patients showed that cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) was superior to pharmacological intervention (cyclobenzaprine) during treatment and follow-up.103 Small studies of electromypgraphy and electro–encephalography biofeedback also suggests that it has the potential of being effective.105, 106 Pilot and small studies of hypnosis also advocate continued investigation.107–110

Small-scale evaluation of mindfulness meditation indicated that 8 by 2.5 sessions of mindfulness-based stress reduction may reduce the depressive symptoms in women with fibromyalgia.111 A trial of meditation-based stress management during a 10-week outpatient group programme indicated effectiveness, however, identified a specific subgroup (51%) of responders who gained through better sleep, reduced fatigue and increased feelings of rejuvenation in the morning.112 A 7-week trial of qigong indicated potential benefits amongst 29 female fibromyalgia patients,113 however a combined meditation–qigong intervention was found to be only equivalent to education and support.114 The use of guided imagery focusing on pleasant imagery as a distraction from the pain of fibromyalgia was found to be effective, however the use of attention imagery was not.115 Relaxation and guided imagery was also found to be of benefit in a small trial of Hispanic patients.116

In summary, while various mind–body therapies have been recommended for fibromyalgia and pooled evidence is suggestive of benefit,117 further evidence is required before we can conclude definitive benefits for specific treatment approaches.

Physical activity

A Cochrane review (2007) identified exercise as being moderately beneficial in certain aspects of fibromyalgia management depending on the type of exercise. Aerobic exercise (a moderate intensity 12-week programme) may increase feelings of wellbeing and function, although may not effect pain or tender point number. Strength training has been noted to reduce pain, tender points, depression and wellbeing, although not physical function. Exercise programmes should be initiated in a graded manner and balanced with symptoms. Compliance is often difficult for fibromyalgia patients.118 A 2008 systematic review supported many of these conclusions, however advocated further studies are required.119

In particular, aquatic therapy has been demonstrated to be effective in fibromyalgia.120 Aquatic therapy has been suggested as an introduction for patients who may fear that pain will exacerbate their symptoms.121 While both patients on a home-based exercise programme and undertaking aquatic therapy may benefit from exercise, aquatic therapy appears to have long-term effects on pain reduction.122

Small studies have shown statistically significant benefits for fibromyalgia patients participating in tai chi123 and yoga.124

Nutritional influences

Diet

Evidence is weak regarding the benefits of diet on fibromyalgia. A pilot study on the effects of weight loss on fibromyalgia suggests that a behavioural weight loss programme leading to an average 4.4% weight reduction in overweight/obese patients predicted reduced fibromyalgia symptoms, body satisfaction and quality of life.125 While it has been noted by some studies that vegan and predominantly raw vegetable diets may have short-term benefits on fibromyalgia symptoms,126, 127 these results are questionable as other studies indicate vegetarian diets as being of little benefit as compared to medication with amitrytilline.128 A trial of 4 patients demonstrated the possibility that excitotoxin removal (e.g. MSG and aspartamine) may assist in a subgroup of fibromyalgia patients.129 Soy and casein (protein) shakes may also decrease fibromyalgia symptoms.130 In summary, as with many areas of fibromyalgia intervention, evidence is inconclusive due to the low evidential value of current studies.

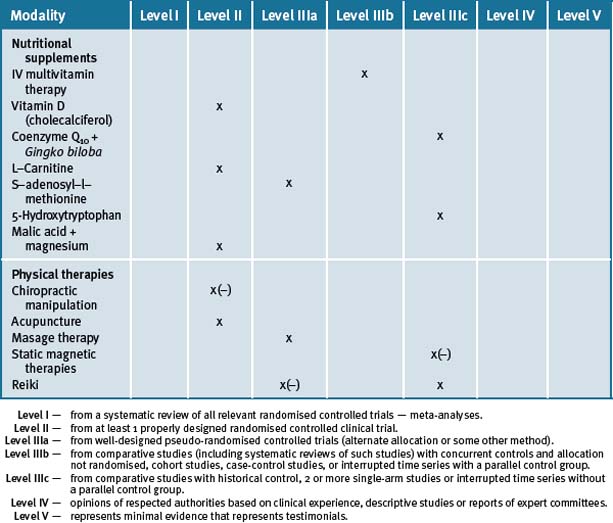

Nutritional supplements

Intravenous vitamin therapy may assist to decrease symptoms and increase function in long-term fibromyalgia patients.131

An open pilot study of 200mg Coenzyme Q10 and 200mg Gingko biloba extract given to fibromyalgia patients for 84 days, resulted in many reporting quality of life improvements; 64% recording that they felt better as compared to 9% stating they felt worse.132 In a second trial, 2 capsules of 500mg acetyl L-carnitine per day over 10 weeks led to an improvement in pain scores and depression as compared to control groups.133

A double-blind placebo cross-over trial of intravenous S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAMe) reported a tendency towards significance in response to pain at rest, pain on movement and wellbeing and only slight improvements in fatigue, quality of sleep and morning stiffness, with no effect on muscle strength.134 A further SAMe injection trial indicated an improvement in tender point scores and associated depression.135 An oral supplementation investigation of SAMe using 800mg daily for 6 weeks demonstrated improvements in clinical disease activity, pain experienced over a week, morning stiffness, mood (as measured by Face Scale) and fatigue, although tender point scores, muscle strength and mood (as evaluated by Beck Depression Inventory) did not differ as compared to a control.136

It has been suggested that the use of 5-Hydroxytryptophan (5-HTH) as a serontonin precursor is effective in treating fibromyalgia, particularly since, unlike tryptophan, it cannot be shunted into niacin or protein production.137 A 90-day open study of 50 patients with 5-HTH demonstrated it was effective in providing good or fair clinical improvement in 50% of patients.138

Vitamin D deficient (25 [OH]D 10-25ng/mL) fibromyalgia patients treated with 50 000 units cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) showed significant improvement in fibromyalgia assessment when treated over an 8-week period. However, those patients considered severely deficient (<10ng/mL) showed no benefit.139 However, these results differ to trials in which ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) 50 000IU once weekly for 3 months did not significantly change fibromyalgia symptoms amongst patients with low vitamin D levels (<20ng/ml).140

Trials of combination treatment with malic acid (1200 to 2400mg) and magnesium (300 to 600mg) over 8 weeks indicated decreases in tender-point measures as early as 48 hours, with resumption of symptoms on cessation.141 A further study at the lowest dosage levels identified that the half dose did not appear significant enough to lead to symptoms reduction, and that the higher double dosage could take up to 2 months to be effective.142

Physical therapies

A 2003 systematic review of chiropractic manipulation for non-spinal conditions including fibromyalgia indicates that there is not enough evidence to suggest that they are effective.143 A further review in 2009 suggested that there was only limited evidence that chiropractic manipulation was effective in treating fibromyalgia.144

In comparison moderate evidence appears to exist for the use of massage therapies (twice per week, 5 weeks) during the course of treatment.145 The sleep of fibromyalgia patients also appears to improve after massage.146 A trial of reiki therapy in fibromyalgia patients indicates that there is little evidence of effectiveness.147

A systematic review (2007) of acupuncture suggests only short-term limited effects such that acupuncture could not be recommended for fibromyalgia.148 However, a subsequent small trial (2008) differs in stating acupuncture may provide quality of life improvements up to 3 months post-treatment.149 It should be noted that the use of sham needling in evaluating acupuncture has been challenged by acupuncturists as being inappropriate to this form of modality.150

The use of static magnetic therapies has been demonstrated to only be as effective as sham or usual treatment.151

Conclusion

Growing knowledge as to the multi-factorial causes, dysfunctions and associations of fibromyalgia indicates that this is a heterogenetic syndrome requiring an essential individualisation of therapy. At present, non–pharmacological treatment evidence remains scant, other than for aerobic and strengthening exercise, yet it is likely that multidisciplinary programmes that provide a combination of mind–body, exercise and supplementation approaches are necessary if maximum achievable gains are to be made by the patient. (See Table 16.1.)

Clinical tips handout for patients — fibromyalgia

1 Lifestyle advice

Sunshine

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine

4 Environment

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Protein supplementation (e.g. rice whey, soy, casein)

Melatonin

Vitamins and minerals

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol)

1 Mease P. Fibromyalgia syndrome: a review of clinical presentation, pathogenesis, outcome measures and treatment. J Rheumatol Supp. 2005 Aug;75:6-21.

2 Neumann L., Buskila D. Epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2003 Oct;7(5):362-368.

3 Wolfe F., Smythe H.A., Yunus M.B., et al. The American College of Rheumatology Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter. Criteria Committee Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1990;33:160-172.

4 Glass J.M. Fibromyalgia and cognition. J Curr Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl 2):20-24.

5 Sephton S.E., Studts J.L., Hoover K., et al. Biological and psychological factors associated with memory function in fibromyalgia syndrome. Health Psychol. 2003 Nov;22(6):592-597.

6 Nampiaparampil D.F., Shmerling R.H. A review of fibromyalgia. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt1):794-800.

7 Kanaan R.A., Lepine J.P., Wessely S.C. The association or otherwise of the functional somatic syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2007 Dec;69(9):855-859.

8 Veale D., Kavanagh G., Fielding J.F., et al. Primary fibromyalgia and the irritable bowel syndrome: different expressions of a common pathogenetic process. Br J Rheum. 1991 Jun 30;3:220-222..

9 Overlapping conditions among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. fibromyalgia and temporomandibular disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2000 Jan 25;160(2):221-227.

10 Buchwald D., Garrity D. Comparison of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and multiple chemical sensitivities. Arch Int Med. 1994 Sep 26;154(18):2049-2053.

11 Slotkoff A.T., Radulovic D.A., Clauw D.J. The relationship between fibromyalgia and the multiple chemical sensitivity syndrome Scand. J Rheumatol. 1997;26(5):364-367.

12 Wahner-Roedler D.L., Elkin P.L., Vincent A. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies by patients referred to a fibromyalgia treatment program at a tertiary care center. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2005 Jan;80(1):55-60.

13 Arnold L.M., Hudson J.I., Hess E.V. Family study of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Mar;50(3):944-952.

14 Buskila D. Genetics of chronic pain states. Best Pract Clin Rheumatol. 21(3), 2007 Jun. 553–47

15 Buskila D., Neumann L. Genetics of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2005 Oct;9(5):313-315.

16 Ablin J.N., Cohen H., Buskila D. Mechanisms of Disease; genetics of fibromyalgia. Nat Clin Pract Rheum. 2006 Dec;2(12):671-678.

17 Carvalho L.S., Correa H., Silva G.C., et al. May genetic factors in fibromyalgia help to identify patients with differentially altered frequencies of immune cells? Clin Exp Immunol. 2008 Dec;154(3):346-352.

18 Yunas M.B., Kanyan-Raman U.P., Kalyan-Raman K. Primary fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndrome: clinical features and muscle pathology. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988 Jun;69(6):451-454.

19 Katz D.L., Greene L., Ali A., et al. The pain of fibromyalgia is due to muscle hypoperfusion induced by regional vasomotor dysregulation. Med Hypotheses. 2007;69(3):517-525. Epub 2007 Mar 21

20 Elert J.E., Rantapaa-Dahiqvist S.B., Henriksson-Larsen K., et al. Muscle performance electromyography and fibre type composition in fibromyalgia and work related myalgia. Scand J Rheumatol. 1992;21(1):28-34.

21 Norregaard J., Bulow P.M., Danneskiold-Samson B. Muscle strength, voluntary activation, twitch properties, and endurance in patients with fibromyalgia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994 Sep;57(9):1106-1111.

22 Simms R.W., Roy S.H., Hrovat M., et al. Lack of association between fibromyalgia syndrome and abnormalities in muscle energy metabolism. Arthritis Rheum. 1994 Jun;37(6):794-800.

23 Elsinger J., Plantamura A., Ayavou T. Glycolysis abnormalities in fibromyalgia. J Am Coll Nutr. 1994 Apr;13(2):144-148.

24 Le Goff. Is fibromyalgia a muscle disorder? Joint Bone Spine. 2006 May;73(3):239-242.

25 Sprot H., Salemi S., Gay R.E., et al. Increased DNA fragmentation and ultrastructural changes in fibromyalgic muscle fibres. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004 Mar;63(3):245-251.

26 Pongratz D.E., Spath M. Morphologic aspects of fibromyalgia. Z Rheumatol. 1998;57(Suppl 2):47-51.

27 Ozgoenmens S., Ozyurt H., Sogut S., et al. Antioxidant status, lipid peroxidation and nitric oxide in fibromalgia: etiologic and therapeutic concerns. Rheumatol Int. 2006 May;26(7):598-603.

28 Altindag O., Celik H. Total antioxidant capacity and the severity of the pain in patients with fibromyalgia. Redox Rep. 2006;11(3):131-135.

29 Bagia S, Tamer L, Sahin G. Free radicals and antioxidants in primary fibromyalgia: an oxidative stress disorder?

30 Ozgocmens S., Ozyurt H., Sodut S. Current concepts in the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia: the potential role of oxidative stress and nitric oxide. Rheumatol Int. 2006 May;26(7):585-597.

31 Cordero M.D., Moreno-Fernandez A.M., deMiguel M., et al. Coenzyme Q10 distribution in blood is altered in patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Biochem. 2009 May;42(7-8):732-735.

32 Akkus S., Naziroglu M., Eris S., et al. Levels of lipid perioxidation and antioxidant vitamins in plasma of patients with fibromyalgia. Cell Bioch Funct. 2009 Mar 14.

33 Al-Allaf A.W., Mole P.A., Paterson C.R. Bone health in patients with fibromyalgia. Rheumatology. 2003 Oct;42(10):1202-1206.

34 Plotnikoff G.A., Quigley J.M. Prevalence of severe hypovitaminosis in patients with persistent, nonspecific musculoskeletal pain. Mayo Clin Prac. 2003 Dec;78(12):1463-1470.

35 Mouyis M., Ostor A.J., Crisp A.J. Hypovitaminosis D among rheumatology outpatients in clinical practice. Rheumatology. 2008 Sep;47(9):1348-1351.

36 Armstrong D.J., Meenagh G.K., Bickle I. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with anxiety and depression in fibromyalgia. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(4):551-554.

37 Bazzichi L., Giannaccini G., Betti L., et al. ATP, calcium and magnesium levels in platelets of patients with primary fibromyalgia. Clin Biochem. 2008;41(13):1084-1090.

38 Schwarz M.J., Offenbaecher M., Neumeister, et al. Experimental evaluation of an altered tryptophan metabolism in fibromyalgia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;532:265-275.

39 Maes M., Verkerk R., Delmeire L., et al. Serotonergic markers and lowered plasma branch chain amino acid concentrations in fibromyalgia. Psychiatry Res. 2000 Dec 4;97(1):11-20.

40 Bazzichi L., Palego L., Giannaccini G., et al. Altered amino acid homeostasis in subjects affected by fibromyalgia. Clin Biochem. 2009 Mar 9.

41 Larson A.A., Giovengo S.L., Michalek J.E. Changes in the concentration of amino acids in cerebrospinal fluid that correlate with pain in patients with fibromyalgia: implications for nitric oxide pathways. Pain. 2000;87(2):201-211.

42 Staud R., Spaeth M. Psychophysical and neurochemical abnormalities of pain processing in fibromyalgia. CNS Spectr. 2008 Mar;13(3 Suppl. 5):12-17.

43 Staud R. Autonomic dysfunction in the fibromyalgia syndrome: postural orthostatic tachycardia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008 Dec;10(6):463-466.

44 Thieme K., Turk D.C. Heterogeneity of psychophysiological stress responses in fibromyalgia syndrome patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(1):R9.

45 Torpy D.J., Papanicolaou D.A., Lotsikas A.J., et al. Responses of the sympathetic nervous system and the hypoithalamic-pituatary-adrenal axis to interleukin-6: a pilot study in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2000 Apr;43(4):872-880.

46 Geenen R., Jacob J.W., Bijisma J.W. Evaluation and management of endocrine dysfunction in fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2002;28(2):389-404.

47 Izquierdo-Alvarez S., Bocos-Terraz J.P., Bancalero-Floes J.L., et al. BMC Res Notes. 2008 Dec 22;1:134.

48 Adler G.K., Kinsley B.T., Hurwitz S., et al. Reduced hypothalamic-pituatary and sympathoadrenal responses to hypoglycaemia in women with fibromyalgia. Am J Med. 1999 May;106(5):534-543.

49 Crofford L.J., Engleberg N.C., Demitrack M.A. Neurohormonal pertunation in fibromyalgia. Baillieres Clin Rmeumatol. 1996 May;10:365-378.

50 Riedel W., Schlapp U., Leck, et al. Blunted ACTH and cortisol responses to systemic injection of corticotrophin releasing hormone (CRH) in fibromyalgia: role of somatostatin and CRH-binding protein. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;966:483-490.

51 Griep E.N., Boersma J.W., de Kloet E.R. Altered reactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in the primary fibromyalgic syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1993 Mar;20(3):469-474.

52 Calis M., Gokce C., Ates F. Investigation of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) by 1microg ACTH test and mtyrapone test in patients with primary fibromyalgia syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2004 Jan;27(1):42-46.

53 Macedo J.A., Hesse J., Turner J.D. Glucocorticoid sensitivity in fibromyalgia patients: decreased expression of corticosteroid receptors and glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper. Psychoneuroendicrinology. 2008 Jul;33(6):799-809.

54 McClean S.A., Willias D.A., Harris R.E., et al. Momentary relationships between cortisol secretion and symptoms in patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Nov;52(11):3600-3609.

55 Crofford L.J., Young E.A., Engleberg N.C., et al. Basal circadian and pulsatile ACTH and cortisol secretion in patients with fibromyalgia and/or chronic fatigue syndrome. Bran Behav Immun. 2004 Jul;18(4):314-325.

56 Soy M., Guidikin S., Arikan E., et al. Frequency of rheumatic diseases in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Rheumatol Int. 2007 Apr;27(6):575-577.

57 Pamuk O.N., Cakir N. The frequency of thyroid antibodies in fibromyalgia patients and their relationship with symptoms. Clin Rheum. 2007;26(1):55-59.

58 Bazzichi L., Rossi A., Giuliano T., et al. Association between thyroid autoimmunity and fibromyalgic disease severity. Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Dec;26(12):2115-2120.

59 Ribiero L.S., Proietti F.A. Interrelations between fibromyalgia, thyroid autoantibodies and depression. J Rheumatol. 2004 Oct;31(10):2036-2040.

60 Bennett R.M. Adult growth hormone deficiency in patients with fibromyalgia. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2002 Aug;4(4):306-312.

61 Bennet R.M. Growth hormone in musculoskeletal pain states. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2005 Oct;9(5):331-338.

62 Jones R.D., Deodhar P., Lorentzen A., et al. Growth hormone perturbations in fibromyalgia: a review. Semim Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Jun;36(6):357-379.

63 Harding S.M. Sleep in fibromyalgia patients: subjective and objective findings. Am J Med Sci. 1998 Jun;315(6):367-376.

64 Theadon A., Cropley M. Dysfunctional beliefs, stress and sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia. Sleep Med. 2008 May;9(4):376-381.

65 Wilkner J., Hirsch U., Wetterberg L., et al. Fibromyalgia – a syndrome associated with decreased nocturnal melatonin secretion. Clin Endocrinol. 1998 Aug;49(2):179-183.

66 Mullington J.M., Hinze-Selch D., Polimacher T. Mediators of inflammation and their interaction with sleep: relevance for chronic fatigue syndrome and related conditions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001 Mar;993:201-210.

67 Lorton D., Lubahn C.L., Estus, et al. Bidirectional communication between the brain and the immune system: implications for physiological sleep and disrupted sleep. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2006;13(5-6):357-374.

68 Van West D., Maes M. Neuroendocrine and immune aspects of fibromyalgia. Biodrugs. 2001;15(8):521-531.

69 Haheim L.L., Nafstad P., Olsen I., et al. C-reactive protein variations for different chronic somatic disorders. Scand J Public Health. 2009 Apr 16.

70 Rea T., Russo J., Katon W., et al. A prospective study of tender points and fibromyalgia during and after an acute viral infection. Arch Intern Med. 1999 Apr 26;159(8):865-870.

71 Wittrup I.H., Jensen B., Biddal H., et al. Comparison of viral antibodies in 2 groups of patients with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2001 Mar;28(3):601-603.

72 Douche-Aourik F., Serleir F., Ferasson L., et al. Detection of enterovirus in human skeletal muscle from patients with chronic inflammatory muscle disease or fibromyalgia and healthy subjects. J Med Virol. 2003;71(4):540-547.

73 Nasralia M., Naier J., Nicolson G.L. Multiple mycoplasmal infections in blood of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and/or fibromyalgia syndrome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999 Dec;18(12):859-865.

74 Garrison R.L., Breeding P.C. A metabolic basis for fibromyalgia and its related disorders: the possible role of resistance to thyroid hormone. Med Hypotheses. 2003 Aug;61(2):182-189.

75 Cruz B.A., Catalan-Soares B., Proietta F. Higher prevalence of fibromyalgia in patients infected with human T cell lymphotropic virus type 1. J Rheumatol. 2006 Nov;33(11):2300-2303.

76 Narvaez J., Nolla J.M., Valverde-Garcia J. Lack of association of fibromyalgia with hepatitis C virus infection. J Rheumatol. 2005 Jun;32(6):1118-1121.

77 Narvaez J., Nolla J.M., Valverde J. Joint Bone Spine. 2005 Dec;73(6):592-594.

78 Othman M., Aguero R., Lin H.C. Alterations in intestinal microbial flora and human disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008 Jan;24(1):11-16.

79 Wallace D.J., Hallequa D.S. Fibromyalgia: the gastrointestinal system. Curr Pain Headache Resp. 2004 Oct;8(5):364-368.

80 Thieme K., Turk D.C., Flor H. Comorbid depression and anxiety in fibromyalgia syndrome: relationship to somatic and psychosocial variable. Psychosom Med. 2004 Nov-Dec;66(6):837-844.

81 McBeth J., Macfarlane G.J., Benjamin S., et al. Features of somatisation predict the onset of chronic widespread pain: results of a large population based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001 Apr;44(4):940-946.

82 Walker E.A., Keegan D., Gardner G. Psychosocial factors in fibromyalgia compared with rheumatoid arthritis: I. Psychiatric diagnoses and functional disability. Psychosom Med. 1997 Nov-Dec;59(6):565-571.

83 Bergman S. Psychosocial aspects of chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia. Disabil Rehabil. 2005 Jun 17;27(12):675-683.

84 Sherman J.J., Turk Dc. Okifuji Prevalence and impact of posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms on patients with fibromyalgic syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2000 Jun;16(2):127-134.

85 Boisset-Piero M.H., Esdalle J.M., Fitzcharles M.A. Sexual and physical abuse in women with fibromyalgia syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Feb;38(2):235-244.

86 Walker E.A., Keenan D., Gardner G., et al. Psychosocial factors in fibromyalgia compared with rheumatoid arthritis: II Sexual, physical and emotional abuse and neglect. Psychosom Med. 1997 Nov-Dec;59(6):572-577.

87 Van Houdenhove B., Neerinchx E., Lysens R., et al. Victimisation in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia in tertiary care: a controlled study on prevalence and characteristics. Psychosomatics. 2001 Jan Feb;42(1):21-28.

88 Ruiz- Perez I., Plazaola-Castano J., Caliz-Caliz R., et al. Risk factors for fibromyalgia the role of violence against women. Clin Rheum. 2009 Mar 10.

89 Ciccone D.S., Elliot D.K., Chandler H.K., et al. Sexual and physical abuse with fibromyalgia syndrome: a test of the trauma hypothesis. Clin J Pain. 2005 Sep Oct;21(5):378-386.

90 Kivimaki M., Leiros-Arjas P., Virtanen M., et al. Work stress and incidence of newly diagnosed fibromyalgia: prospective cohort study. J Psychosom Res. 2004 Nov;57(5):417-422.

91 Yunus M.B., Arsian S., Aldag J.C., et al. Relationship between fibromyalgia and smoking. Scand J Rheumatol. 2002;31(5):301-305.

92 Weingarten T.N., Podduturu V.R., Hooten W.M., et al. Impact of tobacco use in patients presenting to multidisciplinary outpatient treatment programme in fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 2009 Jan;25(1):39-43.

93 Pamuk O.N., Donmez S., Cakir N. The frequency of smoking in fibromyalgia patients and its association with symptoms. Rheumatol Int. 2009 Jan 20.

94 Neumann L., Lerner E., Glazer Y., et al. A cross-sectional study of the relationship between body mass index and clinical characteristics, tenderness measures, quality of life and physical function in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Dec;27(15):1543-1547.

95 Yunus M.B., Arsian S., Aldag J.C. Relationship between body mass index and fibromyalgia features. Scand J Rheumatol. 2002;31(1):27-31.

96 Burckhardt C.S., Mannerkorpi K., Hedenberg L., et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of education and physical training with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1994 Apr;21(4):714-720.

97 Havermark Am, Ekiof Languis. A Long term follow up of a physical therapy programme for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Scand J Caring Sc. 2006 Sep;20(3):315-322.

98 Keel P.J., Bodoki C., Gerhard U., et al. Comparison of integrated group therapy and relaxation training for fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 1998 Sep;14(3):232-238.

99 Creamer P., Singh B.B., Hochberg B.M. Sustained improvement produced by nonpharmacological intervention in fibromyalgia: results of a pilot study. Arthritis Care Research. 2000 Aug;13(4):198-204.

100 Karjalainen K., Malmivaara A., van Tulder M., et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for fibromyalgia and musculoskeletal pain in working age adults. Cochrane Date Base Systematic Review. (2):2000. CD001984

101 Goldenberg D.L. Multidisciplinary modalities in the treatment of fibromyalgia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl 2):30-34.

102 Lemstra M, Olsznski WP. The effectiveness of multidisciplinary rehabilitation in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomised controlled trial. Clin J Pain Mar-Apr;21(2):166-174

103 Angst F., Brioschi R., Main C.J. Interdisciplinary rehabilitation in fibromyalgia and chronic back pain: a prospective outcome study. J Pain. 2006;7:807-815.

104 Garcia J., Simon Ma, Duran M. Differential efficacy of a cognitive behavioural intervention versus pharmacological treatment in the management of fibromyalgic syndrome. Psychol Health Med. 2006 Nov;11(4):498-506.

105 Babu As, Matthew E., Danda D. Management of patients with fibromyalgia using biofeedback: a randomised control trial Indian. J Med Sci. 2007 Aug;61(8):455-461.

106 Kayiran S., Dursan E., Ermutiu N. Neurofeedback in fibromyalgia. Agri. 2007 Jul;19(3):47-53.

107 Castel A., Perez M., Sala J., et al. Effect of hypnotic suggestion on fibromyalgic pain: comparison between hypnosis and relaxation. Eur J Pain. 2007 May;11(4):463-468.

108 Martinez-Valero C., Castel A., Capafons A., et al. Hypnotic treatment synergizes the psychological treatment of fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Am J Clin Hyn. 2008 Apr;50(4):311-321.

109 Alvarez-Nemegyei J., Negreros-Castillo A., Nuno-Gutierrez B.L., et al. Eriksonian hypnosis in women with fibromyalgia syndrome. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2007 Jul-Aug;45(4):395-401.

110 Derbyshire SW, Whalleymg, Oakley DA. Fibromyalgia pain and its modulation by hypnotic and non-hypnotic suggestion: an MRI analysis.

111 Sephton S.E., Salmon P., Weissbecker I., et al. Mindfulness meditation alleviates symptoms in women with fibromyalgia: results of a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Feb 15;57(1):77-85.

112 Kaplan K.H., Goldenberg D.L., Galvin Nadeau M. The impact of a meditation-based stress reduction program on fibromyalgia. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993 Sep;15(5):284-289.

113 Haak T, Scott The effect of Qigong on fibromyalgia (FMS): a controlled randomized study Disabil Rehabil 30(8):625–33.

114 Astin J.A., Berman B.M., Bausell B., et al. The efficacy of mindfulness meditation plus Qigong movement therapy in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2003 Oct;30(10):2257-2262.

115 The effect of guided imagery and amitriptyline on daily fibromyalgia pain. a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2002 May-Jun;36(3):179-187.

116 Menzies V., Kim S. Relaxation and guided imagery in Hispanic persons diagnosed with fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Fam Community Health. 2008 Jul-Sep;31(3):204-212.

117 Hadhazy V.A., Ezzo J., Creamer P., et al. Mind-body therapies for the treatment of fibromyalgia. A systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2000 Dec;27(12):2911-2918.

118 Busch A.J., Barber K.A., Peloso P.M.J., et al. Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (4):2007. Art No.: CD0003786

119 Busch A.J., Schachter C.L., Overend T.J., et al. Exercise for fibromyalgia: a systematic review. J Rheumatol. 2008 Jun;35(6):1130-1144.

120 McVeigh J.G., McGaughey H., Hall M., et al. The effectiveness of hydrotherapy in the management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int. 2008 Dec;29(2):119-130.

121 Gowan S.E., deHueck A. Pool exercise for individuals with fibromyalgia. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007 Mar;19(2):168-173.

122 Ecvik D., Yigit I., Pusak H. Rheumatol Int. 2008 Jul;28(9):885-890.

123 Taggart H.M., Arsianian Cl, Baea, et al. Effects of Tai Chi exercise in fibromyalgia symptoms and health relates quality of life. Orthop Nurs. 2003 Sep-Oct;22(5):353-360.

124 Da Silva G.D., Lorenzi-Filho G., Lage L.V. Effects of yoga and the addition of Tui Na in patients with fibromyalgia. J Altern Complement Med. 2007 Dec;13(10):1107-1113.

125 Shapiro J.R., Anderson D.A., Danoff-Burg S. A pilot study of the effects of behavioural weight loss treatment on fibromyalgia symptoms. J Psychosom Res. 2005 Nov;59(5):275-282.

126 Kaartinen K., Lammi K., Hypen M., et al. Vegan diet alleviates fibromyalgia symptoms. Scand J Rheumatol. 2000;29(5):308-313.

127 Donaldson M.S., Speight N., Loomis S. Fibromyalgia syndrome improved using a mostly raw vegetarian diet: an observational study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2001;1:7.

128 Azad K.A., Alam M.N., Haq S.A., et al. Vegetarian diet in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2000 Aug;26(2):41-47.

129 Smith J.D., Terpening C.M., Schmidt S.O., et al. Relief of fibromyalgia symptoms following discontinuation of dietary excitotoxins. Ann Pharmacother. 2001 Jun;25(6):702-706.

130 Wahner-Roedler D.L., Thompson J.M., Luedtke C.A. Dietary Soy Supplement on Fibromyalgia Symptoms: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, early phase trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008 Nov 6.

131 Massey P.B. Reduction of fibromyalgic symptoms through intravenous nutrient therapy: results of a pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007;13(3):32-34.

132 Lister R.E. An open, pilot study to evaluate the potential benefits of coenzyme Q10 combined with Gingko biloba extract in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Int Med Res. 2002;30(2):195-199.

133 Rossine M., Di Munno O., Valentini G., et al. Double-blind, multicentre trial compating acetyl l carnitine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007 Mar-Apr;25(2):182-188.

134 Volkmann H., Norregard S., Danneskoid-Samsoe B., et al. Double-blind placebo controlled cross-over study of intravenous S-adenyl-L-methionine in patients with fibromyalgia. Scand J Rheum. 1997;26(3):206-211.

135 Tavoni A., Vitali C., Bombardieri S., et al. Evaluation of S-adenosylmethionine in primary fibromyalgia. A double-blind crossover study. Am J Med. 1987 Nov 20;83(5A):107-110.

136 Jacobsen S., Danneskioid-Samsoe B., Andersen R.B. Oral S-adenosylmethionine in primary fibromyalgia.Double-blind clinical evaluation. Scand J Rheum. 1991;20(4):294-302.

137 Birdsall T.C. 5-Hydroxytryptophan: a clinically effective serotonin precursor. Altern Med Rev. 1998 Aug;3(4):271-280.

138 Sarzi Puttini P., Caruso I. Primary fibromyalgia syndrome and 5-Hydroxy-L-tryptophan: a 90 day open trial. J Int Med Res. 1992 Apr;20(2):182-189.

139 Arvold D.S., Odean M.J., Dornfeld M.J., et al. Correlation of symptoms with vitamin D deficiency and symptoms responses to cholecalciferol treatment: a randomised controlled trial. Endocr Prac. 2009 May-Jun;15(3):203-212.

140 Diffuse musculoskeletal pain is not associated with low vitamin D levels or improved by treatment with Vitamin D. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008 Feb;14:12-16.

141 Abraham G.E., Flechens J.D. Management of fibromyalgia: rational for use of magnesium and malic acid. J Nutr Med. 1992:349-359.

142 Russell I.J., Michalek J.E., Flechas J.D., et al. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with Supper Malic: a randomised double-blind. Placebo controlled, cross over study. J Rheumol. 1995;22(5):953-958.

143 Ernst E. Chiropractic manipulation for non-spinal pain-a systematic review. NZ Med. 2003 Aug 8;116(1179):U539.

144 Schneider M., Vernon H., Ko G., et al. Chiropractic management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review of the literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2009 Jan;32(1):25-40.

145 Sunshine W., Field T.M., Quintino O., et al. Fibromyalgia benefits from massage therapy and transcutaneous electrical stimulation. L Clin Rheumatol. 1996 Feb;2(1):18-22.

146 Field T., Diego M., Cullen C., et al. Fibromyalgia pain and substance P decreases and sleep improves after massage therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2002 Apr;8(2):72-76.

147 Assefi N., Bogart A., Goldberg J., et al. Reiki for the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomised controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2008 Nov;9:14..

148 Mayhew E., Ernst E. Acupuncture for fibromyalgia – a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J Rheumatology. 2007 May;46(5):801-804.

149 Targino R.A., Imamura M., Kaziyama H.H., et al. A randomised controlled trial of acupuncture added to usual treatment for fibromyalgia. J Rehabil Med. 2008 Jul;40(7):582-588.

150 Lundeberg T., Lund I. Are reviews based on sham acupuncture procedures in fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) valid? Acupunct Med. 2007 Sep;25(3):100-106.

151 Alfano A.P., Taylor A.G., Foresman P.A., et al. Statics magnets fields for treatments of fibromyalgia: a randomised controlled trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2001 Feb;7(1):53-64.