86 Fever of Unknown Origin

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for FUO can be broadly divided into the following categories: infection, collagen vascular or autoimmune, and malignancy. A number of case series have followed children who were evaluated for FUO to determine the underlying etiology of fever in these patients (Table 86-1). Many of these reports are decades old and may not comprise the underlying infectious etiologies of FUO because of the advancement of clinical microbiologic laboratory and diagnostic imaging modalities, as well as the emergence of novel pathogens. Nonetheless, these studies are informative in that the most commonly identified etiologies for FUO have remained stable through time.

Table 86-1 Underlying Diagnosis in Fever of Unknown Origin in 545 Patients from Compiled Case Reports

| Diagnosis | Total (n) | Established Diagnoses (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Infectious | 262 | 62 |

| Epstein-Barr virus | 26 | 6 |

| Viral syndrome | 22 | 5 |

| Urinary tract infection | 22 | 5 |

| Pneumonia | 19 | 4 |

| Osteomyelitis | 18 | 4 |

| Viral meningitis or encephalitis | 17 | 4 |

| Bacterial meningitis | 14 | 3 |

| Pharyngitis or tonsillitis | 14 | 3 |

| Viral upper respiratory infection | 12 | 3 |

| Streptococcosis | 9 | 2 |

| Otitis media | 8 | 2 |

| Bartonellosis | 8 | 2 |

| Bacterial enteritis | 7 | 2 |

| Viral gastroenteritis | 7 | 2 |

| Sinusitis | 6 | 1 |

| Subacute bacterial endocarditis | 5 | 1 |

| Tuberculosis | 5 | 1 |

| Rickettsial infection | 5 | 1 |

| Cytomegalovirus | 5 | 1 |

| Tularemia | 4 | 1 |

| Other Infections | 29 | 7 |

| Collagen Vascular or Autoimmune | 65 | 15 |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | 28 | 7 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 11 | 3 |

| Rheumatic fever | 7 | 2 |

| Other collagen vascular | 19 | 4 |

| Malignancy | 27 | 6 |

| Leukemia | 14 | 3 |

| Lymphoma | 4 | 1 |

| Other malignancy | 9 | 2 |

| Other | 65 | 17 |

| Drug reaction | 8 | 2 |

| Factitious fever | 6 | 1 |

| Miscellaneous | 51 | 14 |

| Total established diagnoses | 426 | 78 |

| Diagnosis unknown | 119 | 22 |

Infection

Viral Infections

Viral infections are frequent causes of FUO in children. Although these infections are generally self-limited, their identification can help avoid further testing and imaging in patients in whom a diagnosis has not been established. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) remains one of the most common causes of FUO in children. Other systemic viral infections responsible for FUO include systemic cytomegalovirus (CMV), enterovirus, and adenovirus. Viruses in the herpes family, particularly human herpesvirus-six (HHV-6), are commonly found in children and may present with prolonged isolated fever. Newer molecular techniques for identification of parvovirus have demonstrated its prevalence in children with fever. Finally, HIV is a possible source of FUO, both acutely and chronically, in association with opportunistic infections (see Chapter 95).

Collagen Vascular and Autoimmune Disorders

Fever may be a major presenting symptom in many noninfectious inflammatory conditions. Among these, the acute onset of fever occurs most commonly in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis and Kawasaki’s disease (KD) (see Chapters 26 and 28). The incidence of KD varies greatly with geography. In the United States, the average incidence ranges between 3.1 and 8.9 cases per 100,000 children per year. Apart from being the more common noninfectious inflammatory causes of fever among children, these disorders are important because they require early recognition and treatment to prevent long-term complications.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) accounts for a subset of patients with FUO, although this entity does not usually present with isolated fever but rather with multiorgan involvement. Apart from KD, other vasculitides may present with fever in addition to other organ involvement. Juvenile Behçet’s disease in children older than age 1 year may include fever as a symptom, and polyarteritis nodosa should be considered in older children with fever and muscle and skin involvement. Remaining identified vasculitides are either very rare in children or are unlikely to present with isolated fever, such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura (see Chapter 28).

Recurrent intermittent fevers may occur as part of a periodic fever syndrome. The most commonly encountered of these is periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis disease (PFAPA). The syndrome is rarely associated with fevers that last longer than 1 week. The hereditary fever disorders are far less common but are potential etiologies of recurrent fevers in children. One hereditary fever syndrome that may present with prolonged fever is tumor necrosis factor receptor–associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). In young children and especially infants with persistent or recurrent fevers, an underlying immunodeficiency should be considered (see Chapter 21).

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly Crohn’s disease, has become an important diagnostic consideration in children with FUO. Because this entity may be difficult to diagnose at an early age, patients may present with a history of prolonged isolated fever and growth failure with or without intestinal manifestations (see Chapter 110).

Approach to the Patient

In a well-appearing child who continues to thrive, the evaluation for FUO may be performed in the outpatient setting. A thorough history will offer many clues to the potential etiology of FUO and will help guide the appropriate diagnostic workup. The major exception to this is a an infant younger than 90 days old with fever. Because fever is a less common but more concerning presenting sign in this population, these patients warrant an immediate laboratory evaluation to assess for serious bacterial infections (see Chapter 105).

History

The child’s overall state of health should be described, including activity level and appetite. A history of any localizing or coexisting symptoms should be elicited because they may help target the investigation (Table 86-2). The patient’s age and any underlying conditions may offer clues to the diagnosis and help to organize the differential diagnosis. A thorough medication history should be recorded, particularly when considering drug fever. A detailed family history should explore for family members with a history of rheumatologic conditions, malignancy, or IBD.

Table 86-2 Localizing Symptoms in Patients with Fever of Unknown Origin

| Organ System | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Central nervous system | Headache |

| Neck stiffness | |

| Lethargy or irritability | |

| Personality or cognitive changes | |

| Respiratory | Nasal congestion or rhinorrhea |

| Sinus pain | |

| Otalgia | |

| Cough | |

| Dyspnea | |

| Chest pain | |

| Hemoptysis | |

| Ocular | Painful or dry eyes |

| Ocular discharge | |

| Oral | Oral ulcers |

| Gastrointestinal | Abdominal pain |

| Abdominal distension | |

| Changes in appetite | |

| Vomiting | |

| Diarrhea | |

| Hematochezia | |

| Genitourinary | Dysuria, frequency, urgency |

| Back pain | |

| Urethral ulcers or discharge | |

| Musculoskeletal | Extremity or joint swelling or pain |

| Limp or limited extremity use |

Diagnostic Testing

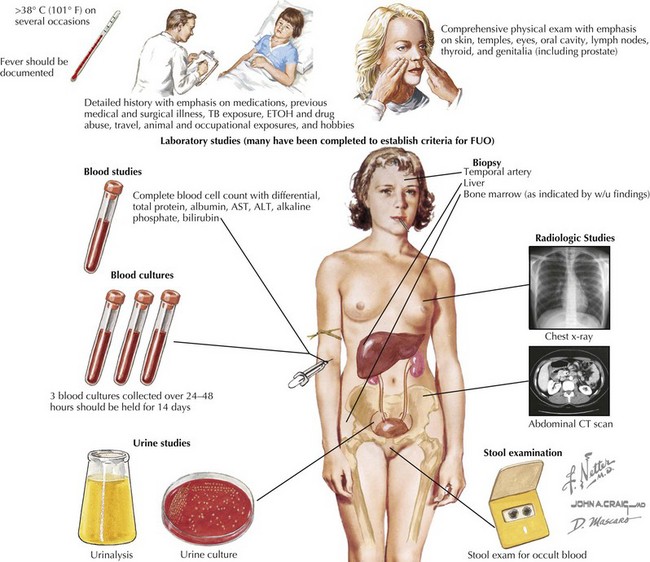

As the sensitivity and availability of laboratory tests and imaging modalities advance, the identifiable underlying causes of FUO in children continue to evolve (Fig. 86-1). Specifically, viral pathogens and fastidious bacteria that were formally difficult to isolate in culture are more easily detected with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing. Additionally, improvements in computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography for imaging the abdominal cavity have virtually eliminated the need for exploratory laparotomy as a final resort in diagnosis in FUO. Finally, newer techniques in positron emission tomography (PET) scanning allow for identification of regions with increased metabolic activity, making it possible to find potential sources of FUO even in the absence of localizing clinical signs. Still, the diagnostic workup should proceed in a stepwise fashion, using the history and physical examination to guide the testing modalities selected for each patient.

Screening Evaluation

An initial screening laboratory evaluation is appropriate and may be performed in the outpatient setting (Box 86-1). A complete blood count with differential may be very revealing. An elevated white blood cell count is a nonspecific sign of inflammation, but the degree of elevation is informative. The types of cells that are prominent in the differential count may point toward the source of inflammation. In addition, some infections are associated with leucopenia as well. Microcytic anemia can occur in the setting of chronic disease. Thrombocytosis is a nonspecific marker of inflammation because platelets are acute phase reactants. The suppression of cell lines may point to a rheumatologic or hematologic or neoplastic process. Inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate are not specific if elevated, but they give an overall impression of level of inflammation. Baseline inflammatory markers are useful in tracking the course of illness. Urinalysis, urine culture, and blood culture should be obtained in all patients. A complete metabolic profile may demonstrate transaminitis or indicate impaired kidney function. Chest radiography is part of the initial evaluation of all patients and may identify parenchymal disease, pulmonary nodules, hilar adenopathy, or cardiomegaly. A purified protein derivative tuberculin skin test should be done on all patients, regardless of known risk factors for infection with TB.

Laboratory Testing

Although antineutrophil antibodies are a poor screening test for all rheumatologic conditions, this test should be obtained if a concern for SLE exists. Because other collagen vascular conditions are made on a clinical basis, additional laboratory testing should not be used in a “shotgun” approach to rule out rheumatologic and autoimmune conditions (see Chapter 26).

Bleeker-Rovers C, van der Meer J, Oyen W. Fever of unknown origin. Semin Nucl Med. 2009;39:81-87.

Cunha B. Fever of unknown origin: clinical overview of classic and current concepts. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:867-915.

Feigin RD, Shearer WT. Fever of unknown origin in children. Curr Prob Pediatr. 1976;6:3-64.

Hofer M, Mahlaoui N, Prieur A-M. A child with a systemic febrile illness: differential diagnosis and management. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006;20:627-640.

Jacobs R, Schutze G. Bartonella henselae as a cause of prolonged fever and fever of unknown origin in children. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:80-84.

Lohr JA, Hendley JO. Prolonged fever of unknown origin: a record of experiences with 54 childhood patients. Clin Pediatr. 1977;16:768-773.

McCarthy P. Fever. Pediatr Rev. 1998;19:401-408.

McClung HJ. Prolonged fever of unknown origin in children. Am J Dis Child. 1972;124:544-550.

Pizzo PA, Lovejoy FH, Smith DH. Prolonged fever in children: review of 100 cases. Pediatrics. 1975;55:468-473.