Mixed echos, may include cystic areas, hemorrhage or calcification

calcifications

Right sided

May be very large

Central nervous system tumors

CNS tumors comprise 10% of all prenatally diagnosed tumors with most being supratentorial, in marked contrast to pediatric tumors, which are mostly infratentorial[2]. Generally the prognosis is poor and worse if the diagnosis is made prior to 30 weeks where mortality secondary to severe hydrocephalus can be up to 96%[3].

Most CNS tumors will be identified as an intracranial mass with associated hydrocephalus, macrocephaly or polyhydramnios. The mainstay of diagnosis should be to identify potentially curable CNS tumors, such as choroid plexus papillomas, from rapidly fatal ones, such as teratomas or neuroepithelial tumors. The use of fetal MRI may aid determination of tissue type.

Hydrocephalus and macrocephaly develop secondary to obstruction of the ventricular system and cerebrospinal fluid outflow. Rapid growth of a tumor may also lead to macrocephaly secondary to tumor size or the development of hydrops due to cardiovascular compromise. Twenty-one percent of fetuses with CNS tumors will be stillborn as a result of these complications[4]. Due to the high incidence of hemorrhage (18%) in CNS tumors, all diagnoses of intracranial hemorrhage should include assessment of the possibility of an underlying brain lesion. Pediatric neurosurgeons should be involved in the development of a multidisciplinary management plan. Delivery may be complicated by the presence of significant macrocephaly and cesarean section or predelivery decompression of the skull may be required to prevent labor dystocia.

Teratoma

Although rare in older children, intracranial teratoma is the most common CNS tumor in the fetus (>50%)[5]. Most will be located within the ventricles, hypothalamic, suprasellar or cerebral regions. As with all teratomas, they appear as an irregular solid and cystic echogenic mass with calcifications that distort the normal appearance of the brain. Teratomas comprise tissue from all three germ cell layers with immature neuroglial elements. Prognosis is extremely poor and is related to the size of the tumor and presence of associated hydrocephalus. A third will die in utero with only 12% surviving the neonatal period and 7% reaching 1 year of age[5].

Astrocytomas

Astrocytomas are the second most common congenital CNS tumor and represent a wide range of pathologies from subependymal giant cell astrocytomas to glioblastoma multiforme[5]. The appearances on ultrasound are of a unilateral echogenic mass within the cerebral hemisphere, which may have internal hemorrhage and often causes midline shift. The prognosis is generally poor with 13% stillborn and 37% surviving the neonatal period. The situation is even worse in the more aggressive glioblastoma multiforme where only 13% will survive[4].

Ependymoma

Ependymomas are tumors of the ependymal cells lining the ventricles or spinal canal. Ultrasound appearances are of mixed echogenic masses arising from the ventricle, which may include cystic areas, hemorrhage or calcification. They commonly arise from the fourth ventricle. There can be extension into the subarachnoid space with resultant involvement of the spinal cord. Macrocephaly and hydrocephalus are common features, and stillbirth, intracerebral hemorrhage and labor dystocia are complications.

Neuroepithelial tumors/medulloblastoma

Tumors comprised of neuroepithelial tissue can be termed primitive neuroepithelial tumors or medulloblastoma, and whilst common in the pediatric population, this is a much less common finding in the perinatal period. Unlike most other perinatal CNS tumors they are often infratentorial, arising from the cerebellar vermis and extending into the fourth ventricle. Survival is very poor at 12%[6].

Choroid plexus tumor

Tumors of the choroid plexus are rare and mostly papillomas or occasionally carcinomas. They represent 20% of congenital brain tumors and are less common in older children. The hallmark of choroid plexus tumors is excessive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) production with associated hydrocephalus and macrocephaly. The appearance on ultrasound is of a large lobulated highly echogenic (cauliflower-like) mass, usually unilateral and located in the atria of the lateral ventricle, or rarely in the third ventricle. Treatment is with surgical excision, with adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for carcinoma, and survival rates of >70% are common[5].

Craniopharyngioma

These tumors are rare in the perinatal period. When found, they present as large heterogeneous cystic lesions with calcifications. They arise in the suprasellar region from epithelial origin. The prognosis is worse when identified in the perinatal period.

Spinal cord tumors

Congenital tumors of the spinal cord are extremely rare and most commonly are actually saccrococcygeal teratomas. Occasionally astrocytomas can present in this location, and as with most CNS tumors the prognosis is poor.

Differential diagnoses: CNS cysts and vascular malformations

Whilst technically not tumors, these lesions are included as they are important differential diagnoses when investigating CNS lesions.

Choroid plexus cysts

These fluid-filled cystic areas are located within the choroid plexus and form during normal development. They can be found in up to 1% of fetuses on routine ultrasound scanning where they appear as well-circumscribed sonolucent, unilocular or septated cysts >3 mm diameter within the choroid plexus itself. They tend to resolve by the third trimester or soon after birth. They have historically been linked to chromosomal disorders such as trisomy 18, but this risk is low and if found in isolation, does not warrant invasive testing.

Particularly large cysts are usually unilateral and may lead to ventriculomegaly due to obstruction of the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, but in invariably the outcomes are good[7]. Treatment in the neonatal period may be required with removal or fenestration techniques.

Arachnoid cysts

These cysts are benign congenital collections of CSF and may account for 1% of all CNS masses in children. The cysts are lined with collagen arising from the arachnoid mater and there may be communication to the subarachnoid space. Ultrasound appearances are of peripherally placed discrete sonolucent lesion with thin, smooth walls. They are usually supratentorial with the majority located within the sylvian fissure, but they may be found in the posterior fossa[8].

The main effect of arachnoid cysts is as a space-occupying lesion, and therefore the size and location of the cysts can be critical to prognosis. Small cysts may be of no clinical importance, whereas large cysts may cause seizures and neurologic symptoms in the newborn period. Isolated cysts usually have a good prognosis, although regular follow-up is required as they may increase in size in the third trimester leading to the development of hydrocephaly, particularly if located in the posterior fossa. Intrauterine cyst drainage has been attempted for the rapidly enlarging cyst, but usually this can be deferred until after birth.

Arachnoid cysts are usually isolated lesions, but they may be associated with other CNS malformations, such as agenesis of the corpus callosum, absent septum pellucidum, Arnold–Chiari malformation type I, and a variety of chromosomal/genetic syndromes, such as distichiasis-lymphedema, Mohr syndrome, trisomy 18, triploidy and unbalanced translocations. Therefore, amniocentesis should be offered in all cases of arachnoid cysts due to the association with genetic anomalies.

Vein of Galen aneurysm

Aneurysm of the great cerebral vein (of Galen) is extremely rare but relatively easy to diagnose with approximately 50% being diagnosed before infancy. The vein of Galen is part of the network of deep cerebral veins and curves under the splenium of the corpus callosum joining with the inferior sagittal sinus to form the straight sinus. This aneurysmal defect occurs as a result of an arteriovenous malformation between the primitive choroidal vessels and the median prosencephalic vein of Markowski.

Ultrasound appearances are of a well-defined midline sonolucent mass above the corpus callosum and cerebellum extending to the cranium. The use of color Doppler shows a nonpulsatile turbulent flow within the dilated vessel. Additional features within the head include macrocephaly or hydrocephalus. Fetal MRI is important to detect other anomalies and to exclude other differential diagnoses, such as arachnoid, porencephalic or choroid plexus cysts. Common complications include hydrocephaly, high-output cardiac failure and stillbirth. Other sequelae of a vein of Galen aneurysm may occur within the rest of the fetus, and include cardiomegaly, pericardial effusion, dilated neck veins, hepatomegaly, ascites, polyhydramnios and hydrops fetalis. In addition, ballantyne (mirror) syndrome may also present due to a hydropic placenta.

The prognosis for antenatally diagnosed vein of Galen aneurysms is related to the presence of associated cardiac or cerebral anomalies. When other anomalies are present the outcome is invariably poor[9]. For those fetuses that survive to the neonatal period, surgical treatment options exist and some success has been reported with the use of postnatal vein embolization, although the mortality for this procedure is around 30%.

Head and neck tumors

The range of head and neck tumors is significant and includes teratoma, lymphangioma, congenital goitre, thyroid or parathyroid tumors, thyroid cysts, neuroblasmtoma or hamartomas. Tumors of the fetal face usually present early with a persistently open fetal mouth even before the development of associated polyhydramnios. Head and neck tumors may grow large enough to cause obstruction of the fetal airway. If inadequately prepared for, this can be both fatal for the fetus and extremely distressing for the attending clinical team. Other potential complications include polyhydramnios and preterm birth secondary to esophageal obstruction, labor dystocia secondary to tumor size, or spontaneous rupture of the tumor leading to fetal death from exsanguination.

Lymphangioma

Cystic hygroma, otherwise called lymphangioma, is a benign malformation of the lymphatic drainage. They can develop anywhere within the body but commonly affect the neck and thorax. Normally, the lymphatic system begins to form at 5 weeks of gestation. Failure of the jugular lymph sacs to join with the lymphatic system leads to the development of progressively enlarging cystic structures on the lateral and posterior aspects of the neck.

Identification of a cystic hygroma in the first or second trimester carries the risk of fetal demise in utero, and also requires discussion of invasive testing as >50% will have an underlying chromosomal disorder and may also have other anomalies. The common associations include Turner syndrome, Down’s syndrome (trisomy 21), Edward’s syndrome (trisomy 18) and Noonan syndrome. Even with a normal karyotype, the risk of major structural anomalies in these fetuses remains high (34%), predominantly cardiac or skeletal[10]. Overall, a normal outcome can be expected in 17% of fetuses diagnosed with a first-trimester cystic hygroma.

Lymphangioma can also present later in the third trimester after normal routine ultrasound examination. These later onset lymphangiomas are usually located on the anterior neck and the prognosis is generally better. They do not appear to have the same association with aneuploidy or coexistent anomalies.

Appearances on ultrasound are of a large cystic mass with multiple septations commonly observed in the posterior triangle of the neck (Figure 13.1). It may be difficult to differentiate increased nuchal translucency from cystic hygroma at early gestations as both may contains septations[11]. Other differential diagnoses need to be excluded by confirming integrity of the skull (posterior encephalocele) and lack of solid or calcified components (teratoma), ascites or pleural effusions (nonimmune hydrops). If there is doubt, fetal MRI may be beneficial to distinguish between cystic hygroma and cervical teratoma (Figure 13.2).

Ultrasound appearance of a large cervical lymphangioma.

Magnetic resonance imaging appearance of the same cervical lymphangioma shown in Figure 13.1.

Prognosis depends greatly upon gestation at presentation and associated chromosomal or structural anomalies. The majority of early cystic hygromas have a very poor prognosis due to the high incidence of chromosomal abnormalities and hydrops. In the presence of a normal karyotype, no hydrops and no other structural anomalies, the prognosis is excellent.

Management relies upon invasive testing, detailed cardiac assessment, serial scans for progression or compression. Occasionally, amnioreduction will be required due to polyhydramnios secondary to esophageal compression. Vascular compression can lead to nonimmune hydrops, and if the tumor is large elective cesarean section or ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure may be required (Figure 13.3). There is limited data on the use of sclerosing agents for in utero treatment of cystic hygroma but not enough evidence to offer this treatment outside of research protocols.

Cervical lymphangioma from Figures 13.1 and 13.2 following an ex utero intrapartum treatment procedure.

Postnatal management of cystic hygroma relies upon imaging with computed tomography or MRI, followed by surgery or use of sclerosing agents, such as bleomycin. Complete resection is possible in only 77% of cases, with recurrence in 11–52%[12].

Cervical teratoma

These tumors are rare and, in common with other teratomas, consist of tissue from all three germ layers. Due to their location within the neck, the predominant tissue is neural, although 40% may also have thyroid tissue.

Ultrasound commonly demonstrates a large (5–12 cm) multiloculated, unilateral lesion with solid and cystic components. Calcifications may be present in 50% of cases[13]. Extension is commonly to the mandible, mastoid process, suprasternal notch and mediastinum. Involvement of the floor or the oropharynx can lead to mandibular hypoplasia and polyhydramnios.

Management requires repeated ultrasound assessments to monitor tumor growth and liquor volume. Amnioreduction may be required if there is significant polyhydramnios to reduce the likelihood of preterm birth. Stillbirth remains a concern secondary to high-output cardiac failure. Delivery is almost always by cesarean section due to tumor size, hyperextension of the fetal neck and risk of tumor rupture at delivery. Elective intubation at delivery is mandatory and EXIT procedures have been advocated[14] due to the high risk of airway obstruction and respiratory compromise. Even with adequate ventilation, mortality is high at 45% and up to 80–100% in untreated cases. Fetal MRI may help to define the extent of the tumor and allow preparation for an EXIT procedure and postnatal surgery.

Postnatal surgery can be extremely complex and multiple operations may be required to give a good functional and cosmetic result. Endocrine disorders due to loss of thyroid and parathyroid tissue are common but malignant transformation is rare. Recurrence in future pregnancies is extremely rare.

Ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT)

In the fetus with a large neck mass, there is a high risk of airway compromise at birth secondary to laryngeal obstruction or laryngomalacia. If the mass is unrecognized or inadequately planned for, the risk of anoxic brain injury and death is substantial[14].

In cases where a giant neck mass has been identified in the antenatal period appropriate planning of delivery can occur in collaboration with neonatal physicians and ENT surgeons. In these cases it may be appropriate to perform an elective cesarean section with an EXIT procedure (Figure 13.3 and supplementary video).

The EXIT procedure involves delivery of the fetal head and neck at cesarean and establishing a secure airway whilst the fetus is still attached to the placenta. This technique can provide a window of up to 2 h of adequate placental oxygenation in order to secure the airway or even resect the tumor[15]. Once an airway is secured, the rest of the fetus is delivered and separated from the placenta. The main maternal risk from an EXIT procedure is hemorrhage due to the prolonged use of inhalational agents, which relax the uterus.

Cardiac tumors

Fetal cardiac tumors are rare and almost always benign. Most of the cardiac tumors identified in the fetus will be rhabdomyomas, although teratomas and fibromas can also be identified[16]. Due to the location of cardiac tumors, they may have significant effects upon cardiac function or conduction (arrhythmias).

Rhabdomyoma

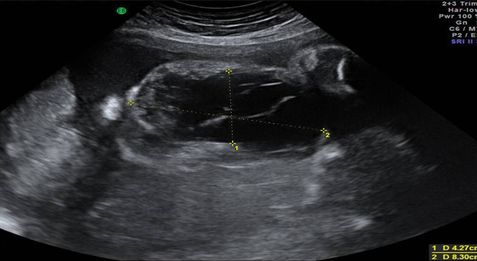

Rhabdomyoma is by far the most common cardiac tumor and is often identified as single or multiple intramural hyperechoic masses (Figure 13.4). Technically, these are hamartomas, an overgrowth of normal tissues, rather than neoplasms. Occasionally, due to the location or size of these masses, they may predispose to cardiac arrythmyias or hydrops due to intracardiac flow disruption. Arrhythmia or cardiac dysfunction are poor prognostic factors and are associated with stillbirth and neonatal death.

Ultrasound appearance of a large septal rhabdomyoma.

The most significant feature of the identification of cardiac rhabdomyomas is their association with tuberous sclerosis, which is present in 50–80% of cases[16]. The presence of multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas is sufficient to give a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosus.

Tuberous sclerosus is an autosomal dominant condition with an incidence of 1 in 6,000, with two-thirds occurring as sporadic mutations. Mutations occur within the tumor suppressor TSC1 or TSC2 genes, located on chromosome 9q34 and 16p13.3, respectively. The resulting hamartoma formation can be lethal. Characteristic features of the condition include mental retardation, epilepsy and facial angiofibromas. Neonatal seizures are common due to cortical and subependymal tubers (gliomas). The use of fetal MRI can significantly aid prognosis as the presence of CNS tubers may provide valuable prognostic evidence that may help decision making regarding continuance of the pregnancy[17]. Antenatal diagnosis of cardiac rhabdomyomas should prompt a careful history and examination of parents and siblings to elucidate family mutations.

Teratoma

The second most commont fetal cardiac tumor is a teratoma but they are far more commonly located elsewhere. Teratomas can originate from the pericardium or less commonly from the myocardium. The most common presentation will be with a mass with a resultant pericardial effusion, or rarely nonimmune hydrops. Stillbirth or neonatal death is an uncommon possibility.

Cardiac fibroma

These are a rare benign tumor of fibroblast or myofibroblast origin often arising from the interventricular septum. Main features relate to left ventricular dysfunction or arrhythmia (ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation). Occasionally, cardiac fibromas may be associated with cleft lip and palate or syndromes such as Beckwith–Wiedeman syndrome or nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome (Gorlin’s syndrome). Cardiac fibromas should be removed surgically after birth to ensure unimpaired cardiac function, although survival can be low (23%) if surgery is performed in the neonatal period[16].

Abdominal and pelvic tumors

The abdomen and pelvis is the most common site for fetal tumors and the tissue of origin is usually readily identified.

Hepatic tumors

The most common cause of a hepatic lesion is not a tumor but actually a hepatic, biliary or choledochal cyst, which require observation and postnatal review.

Hepatic tumors constitute only 5% of fetal tumors[2]. The most common hepatic tumor is a hemangioma. This benign vascular tumor can be singular or multiple and appear heterogeneous when compared with normal liver. Growth can be rapid and lead to cardiovascular compromise, but spontaneous postnatal resolution can occur.

Hamartomas can also occur and are of hepatic, biliary tree or fibrous origin. They appear as solid or mixed cystic lesions on ultrasound and may be associated with Beckwith–Weidemann syndrome[18]. Hepatoblastoma is a malignant tumor of the liver that appears as a solid nodule and is associated with Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome and other malformations.

Neuroblastoma

Neuroblastoma is the most common fetal malignancy and arises from cells of the sympathetic nervous system. Generally these tumors are sporadic but there can be associations with neural crest malformations or a rare familial form (1–2%), which can be screened for[19]. In the nonfamilial form, recurrence is low. The use of folic acid may reduce incidence.

Ninety percent of neuroblastomas are located within the adrenal gland with a right-sided predominance. Ultrasound demonstrates a cystic, solid or mixed appearance. They are normally well circumscribed and cause caudal displacement of the kidney. Fetal MRI may be of assistance in confirming the origin. In utero metastasis to the liver, umbilical cord or placenta has been reported and may lead to hydrops due to compressive effects. Serial ultrasound assessments are required to look for metastases and monitor the size and development of hydrops. Preterm delivery and in utero therapy are not indicated. Maternal complications include pre-eclampsia secondary to secretion of fetal catecholamines, which may be more common in metastatic disease.

Postnatal management usually consists of biopsy to confirm diagnosis and surgery when appropriate. A small number may regress and overall outcome is good with a >90% survival[18].

Renal mass

Tumors of the kidney are rare, with most renal anomalies being due to renal function or cystic lesions. The most common solid renal tumor identified prenatally is a mesoblastic nephroma, which is indistinguishable from Wilm’s tumor (nephroblastoma) on imaging[2]. Appearances are of a unilateral solid homogeneous mass, which may have cystic areas within, representing hemorrhage or necrosis. Polyhydramnios is a common finding, although the exact mechanism of its development is unclear. Tumors are rarely large enough to preclude vaginal delivery.

Assessment for associated anomalies is important as Wilm’s tumor may exist as part of Perlman’s syndrome (ascites, hepatomegaly, macrosomia and polyhydramnios). If Wilm’s tumor is a possibility, a clear history from the mother is required as 20% are associated with mutations of the WT1 gene on chromosome 11.

Ovarian mass

The female fetus may have a tumor arising from the ovary. These are usually cystic follicular or lutein cysts, which regress postnatally. Solid or complex lesions are more likely to represent immature teratomas, which require postnatal resection. Very large lesions >5 cm are at risk of prenatal torsion with resulting ovarian necrosis. Cystectomy with conservation of ovarian tissue should be performed postnatally for persistently large cysts.

Sacrococcygeal teratoma

Teratomas are tumors that have tissue from all three germ cell layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm). Mature teratomas are benign, whereas immature teratomas have malignant potential. They are mostly located within the midline. Over 60% arise from the sacrococcygeal area, with other sites including the gonads (20%), neck, mediastinum, pericardium, retroperitoneum, brain, heart, pharynx and pleura[20].

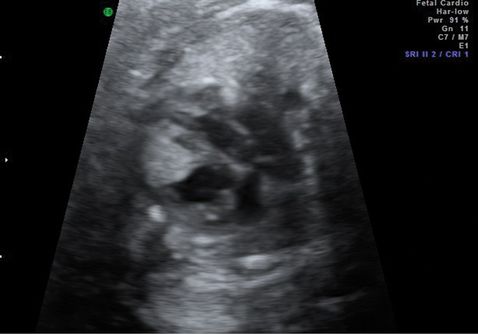

Sacrococcygeal teratomas (SCT) represent the most common congenital neoplasm with a high perinatal morbidity and mortality. The tumor is often large and can be classified in relation to its intra-abdominal contents (Table 13.2)[21]; however, this classification does not give useful information regarding prognosis. SCTs often contain both cystic and solid elements and may be significantly vascularized. Despite these characteristic features antenatal detection is only 50%[22] (Figure 13.5).

Ultrasound of a large sacrococcygeal teratoma at 26 weeks showing the cystic appearance. In this example, the tumor is actually larger than the abdominal circumference.

Supplementary video: video of an ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure performed for massive cervical lymphangioma.

|

Type of sacrococcygeal teratoma tumor as per American Academy of Pediatrics Surgical Section (AAPS)[21] |

|

|---|---|

| Type I | Predominantly external, with minimal intrapelvic extension |

| Type II | Mainly external, with significant intrapelvic extension |

| Type III | Visible external, but predominantly internal |

| Type IV | Internal, although external parts may be visible |

Ultrasound forms the mainstay of management and 3D imaging may aid physicians’ and parents’ understanding of the tumor anatomy. Ultrasound may be less good at determining the extent of pelvic masses due to the “drop out” generated by the bony pelvis, and in these circumstances fetal MRI may have a role to determine the extent of the tumor and its interactions with other tissues.

Isolated SCT is not associated with an abnormal karyotype and amniocentesis is not indicated.

Regular assessment with ultrasound and MRI is required as tumors can grow rapidly and may lead to development of hydrops. Fetal MRI may be superior to ultrasound for the assessment of tumor extension within the abdomen/pelvis.

Congenital teratomas themselves are virtually always benign but should be removed after birth as there is a significant potential for malignant change in the infant period.

Management of fetal tumors

Initial diagnosis and management is likely to be via the fetal medicine unit. It is important to remember that in most cases the management of fetal tumors will involve a multidisciplinary approach, involving fetal medicine specialists, neonatologists, pediatric surgeons or neurosurgeons and midwifes. Pregnancy support groups (www.Bliss.org.uk; www.uk-sands.org) and parent groups may also be useful in providing personalized advice and support to the mother and family of the affected fetus.

The good safety profile and ready availability of ultrasound, supports the use of ultrasound as the primary modality for the detection and follow-up of fetal tumors, especially as repeated assessments are needed.

The use of fetal MRI may be beneficial, particularly when there is uncertainty over tissue of origin or involvement of other organs[2]. The main advantage of fetal MRI is excellent tissue resolution[2].

Summary

Fetal tumors are rare but ultrasound detection is increasingly common in the antenatal period with standard ultrasound based screening modalities. A careful assessment of the tumor location and ultrasound features may aid the determination of tissue type, which could have a significant impact on counseling and request for termination of pregnancy. The use of fetal MRI is beneficial where the tissue of origin or extent of tumor is unclear.

Overall, fetal tumors have a poor prognosis and are associated with high stillbirth rates, labor dystocia and postnatal surgery. However, determination of the underlying tissue type is vitally important as it can drastically alter the prognosis.