Chapter 24 Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The term fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) has been used to describe the diagnostic variations of alcohol-related birth defects that occur as a result of in utero alcohol exposure. FASD refers to “the range of effects that can occur in a person whose mother drank alcohol during pregnancy, including physical, mental, behavioral, and learning disabilities, with possible lifelong implications” (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005). Besides the diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), there are other nondiagnostic variations that include fetal alcohol effects (FAE), alcohol-related birth defect (ARBD), and alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders (ARND).

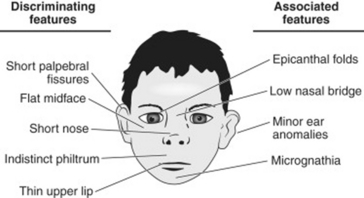

FAS, first described as a syndrome in 1973, refers to the multiple birth defects evident in children as a result of in utero exposure to alcohol during pregnancy. FAS is responsible for the highest number of preventable birth defects and developmental disabilities. FAS is characterized by a triad of symptoms as presented in Box 24-1: (a) three dysmorphic facial features (Figure 24-1), (b) growth retardation, and (c) central nervous system (CNS) problems. Children with FAS may manifest other symptoms in addition to the symptom triad. FAS may be difficult to accurately diagnose since symptoms can be affected by the child’s age and developmental level. Children born with FAE do not have the physical characteristics seen in FAS. The manifestations of FAE are fewer than seen in FAS. Children with FAE demonstrate similar problems observed in children with FAS, such as cognitive, social, and behavioral limitations.

Box 24-1 Characteristics for Diagnosing Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

Facial Dysmorphia

In keeping with racial norms (i.e., those appropriate for a person’s race), the person exhibits all three of the following characteristic facial features:

Growth Problems

Confirmed, documented prenatal or postnatal height, weight, or both, at or below the 10th percentile, adjusted for age, sex, gestational age, and race or ethnicity

Central Nervous System Abnormalities

Functional

Test performance substantially below that expected for a person’s age, schooling, or circumstances, as evidenced by either of the following:

1. Global cognitive or intellectual deficits representing multiple domains of deficit (or substantial developmental delay in younger children), with performance below the 3rd percentile (i.e., two standard deviations below the mean for standardized testing)

2. Functional deficits below the 16th percentile (i.e., one standard deviation below the mean for standardized testing) in at least three of the following domains:

Source: Bertrand J et al: Fetal alcohol syndrome: Guidelines for referral and diagnosis, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC (serial online): www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fas/documents/FAS_guidelines_accessible.pdfwww.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fas/documents/FAS_guidelines_accessible.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2007.

In 1981, the Surgeon General of the United States issued a national report, warning of the dangerous consequences for the fetus of ingesting alcohol during pregnancy. In 1989, federal legislation was passed requiring that all alcohol containers contain warning labels about the deleterious effects of alcohol on the fetus.

The extent to which a child is affected by FAS is dependent on the duration, amount, and pattern of prenatal alcohol exposure and the family situation. The threshold level of alcohol needed to cause FAS is not known; any amount of alcohol consumption is considered unsafe. Damage can occur at any time during pregnancy, even when the woman is not aware that she is pregnant; this is an important factor, since 50% of pregnancies are not planned. Large amounts of alcohol are known to result in harmful fetal effects. The ingestion of seven or more drinks per week and/or of three or more drinks on multiple occasions is considered to have destructive fetal effects.

Alcohol-related risk factors associated with FAS are family member or partner who consumes alcohol, alcohol intake during pregnancy, alcohol dependence, and previous pregnancies with alcohol exposure. Psychosocial factors associated with FAS are low socioeconomic status, parental unemployment, child abuse and neglect, placement of children in foster care, and limited or no prenatal care.

Several challenges are associated with the identification and diagnosis of children with FAS. These challenges include (a) lack of clinical guidelines, (b) the provider’s lack of knowledge, (c) limitations in differentiating FAS from other variations of prenatal alcohol exposure, and (d) the lack of candor with the health care provider on the part of women who consume alcohol during pregnancy. A number of factors have been shown to reduce the long-term consequences of FAS: early diagnosis and intervention, stable home environment, and supportive family environment.

The child with FAS may be first identified in community settings (early intervention program, preschool program) or clinical settings (pediatrician’s office or with a pediatric nurse practitioner in the primary care setting) and then referred to an interdisciplinary team for diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Early diagnosis is essential to implementing programs and services needed to improve long-term outcomes. Diagnosis can be difficult, since the characteristic features of FAS may not be evident.

INCIDENCE

1. Prevalence rates of FAS are 0.2 to 1.5 cases per 1000 births.

2. Prevalence rates of FAE are 3 cases per 1000 births.

3. It is estimated that between 1000 to 6000 children are born with FAS annually.

4. Prevalence rates are higher in disadvantaged, Native American, and culturally diverse populations, amounting to 3 to 6 cases per 1000 births.

5. Most children with FASD do not have cognitive disabilities.

6. Approximately 25% of children diagnosed with FAS score two deviations below the mean on measures of cognitive functioning.

7. Approximately 4 million infants are born with fetal alcohol effects.

8. Of women who become pregnant, 13% to 15% continue to ingest alcohol during pregnancy.

9. Of pregnant women, 3% report engaging in binge or heavy drinking of alcohol.

10. Women who have given birth to a child with FAS are at high risk for giving birth to second child with FAS.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

COMPLICATIONS

FASD is not associated with complications; however, the infant born with FAS may have other secondary diagnoses and long-term problems such as the mental health diagnoses of depression, oppositional defiant disorders, and conduct disorders (Box 24-2). Adaptation problems may occur such as unemployment, dropping out of school, and criminality.

Box 24-2 Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Throughout the Life Span

Infants: Low birth weight; irritability; sensitivity to light, noises and touch; poor sucking; slow development; poor sleep-wake cycles; increased ear infections

Toddlers: Poor memory capability, hyperactivity, lack of fear, no sense of boundaries, need for excessive physical contact

Grade-school years: Short attention span, poor coordination, difficulty with both fine and gross motor skills

Older children: Trouble keeping up with school, low self-esteem from recognition that they are different from their peers

Teenagers: Poor impulse control, cannot distinguish between public and private behaviors; must be reminded of concepts on a daily basis

National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: FASD Intervention (website): www.nofas.org/MediaFiles/PDFs/factsheets/intervention.pdf. Accessed January 10, 2007.

The following problems have been noted in association with FASD:

LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

1. Confirmation of alcohol use during pregnancy

2. Diagnosis is made based on following symptoms (see Figure 24-1 and Box 24-1):

3. Comprehensive neuropsychologic testing

4. Additional diagnostic testing depends on the individualized needs of the child.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

A preventive approach is key to reducing the prevalence of FASD. Preventive strategies include (a) encourage contraception for women who consume alcohol, (b) provide counseling to discourage alcohol consumption, (c) identify at-risk women (those with depression, with history of childhood abuse) of childbearing age who may be inclined to ingest alcohol, and (d) educate providers to assess women of childbearing age who are pregnant who are at risk of having or who have problems with alcohol abuse.

Members of the interdisciplinary team to treat children with FAS include geneticist, developmental pediatrician, nurse, social worker, child psychiatrist, child psychologist, special education specialist, speech and language specialist, and social worker. The extent of interventions will be dependent on the area of the brain affected, the family situation, and the child’s age and developmental level.

Medications may be prescribed, depending on behaviors demonstrated, such as behaviors of impulsivity and hyperactivity, sleep disorders, and oppositional behaviors.

NURSING ASSESSMENT

The assessment process is comprehensive in scope and based on the dimensions of biophysical, psychosocial, behavioral, and educational needs.

1. Assess for the triad cluster of symptoms associated with FAS (see Box 24-1 and Figure 24-1).

2. Assessment consists of comprehensive evaluation of deficits and strengths related to the following adaptive skills:

3. Assess for the manifestations of secondary problems.

4. Assess for long-term adaptation problems.

5. Assess child social behaviors including interactions with others, communication skills, repetitive and stereotypical behaviors, play, and affect.

NURSING DIAGNOSES

• Development, Risk for delayed

• Growth and development, Delayed (related to genetic condition)

• Caregiver role strain (related to unrelenting care requirements secondary to FAS)

• Family processes, Interrupted (related to the impact of raising a child with FAS)

• Parenting, Impaired (related to lack of knowledge)

• Social interactions, Impaired (related to communication barriers and lack of social skills secondary to FAS)

• Therapeutic regimen management, Ineffective family (related to complexity of therapeutic regimen, financial cost of regimen, insufficient social support)

NURSING INTERVENTIONS

Infants, Toddlers, and Preschoolers

1. Refer to early intervention program for development of individualized family service plan (IFSP) and interdisciplinary treatment plan; or, if child, refer to preschool program for individualized education plan (IEP) (see Appendix G) that provides opportunities for developmental learning (Appendix G):

2. Refer parents and caregivers to family resource centers and/or parent information centers that provide early intervention services to parents of infants and toddlers with disabilities for parental support and assistance with informational needs and respite services.

3. Collaborate with other interdisciplinary professionals to formulate IFSP and/or IEP that is based upon individual needs, is family-centered, has measurable objectives, and includes periodic evaluations (refer to the Medical Management section in this chapter).

4. Serve as health resource consultant to community service coordinator.

5. Assist family and child in navigating service systems to obtain needed services for child and family.

6. Refer to the Discharge Planning and Home Care section in this chapter.

School-Aged Children

1. Collaborate with other interdisciplinary professionals to formulate IEP that is based upon individual needs, is individual- and family-centered, has measurable objectives, and includes periodic evaluations.

2. Collaborate with IEP team on identification of health-related needs and development of IEP objectives.

3. Assist family in navigating service systems to obtain needed services for child and family.

4. Provide information and answer family’s questions about strategies to promote the child’s acquisition of developmental milestones (refer to Appendix B).

5. Make suggestions to the family for promotion of the child’s development of self-reliance and sense of mastery.

6. Refer to the Discharge Planning and Home Care section in this chapter.

Adolescents

1. Collaborate with other interdisciplinary professionals to formulate transition IEP that is based upon individual needs, is youth-centered, has measurable objectives, and includes periodic evaluations.

2. Collaborate with IEP team on identification of health-related transition needs and development of IEP objectives.

3. Provide input on transition plan related to health-related needs.

4. Assist family in navigating service systems to obtain needed services for child and family.

5. Serve as health consultant to community service coordinator.

6. Provide information and answer family’s questions about strategies to promote the youth’s acquisition of developmental milestones (refer to Appendix B).

7. Provide the family with suggestions to promote the youth’s development of self-reliance and sense of mastery.

8. Emphasize the importance of creating and taking advantage of socialization opportunities to engage in peer and community activities.

9. Refer to the Discharge Planning and Home Care section in this chapter.

Discharge Planning and Home Care

1. Instruct parents, family members, caregivers, foster parents, and child or youth, and reinforce information, about the short-term and long-term outcomes and prognosis of the FAS diagnosis.

2. Educate parents, family members, and child or youth about long-term management strategies, and community resources needed to access services needed (refer to Appendix G).

3. Refer families to early intervention and/or special education and/or transition programs to address child’s or youth’s needs for treatment services.

4. Participate as a member of an interdisciplinary team in school and/or community settings to develop plan of services to address family- and/or youth-centered goals and objectives based on the child’s or youth’s individualized needs.

5. As appropriate, refer parent to social worker and/or alcohol treatment programs.

CLIENT OUTCOMES

1. Child will be diagnosed early, enabling participation in early treatment and intervention.

2. Child or youth will achieve highest potential of biopsychosocial functioning.

3. Child or youth will achieve highest level of self-sufficiency possible.

4. Child or youth will demonstrate highest achievable level of autonomy, self-determination, and self-advocacy.

5. Family and caregivers will demonstrate ability to cope with child’s or youth’s behaviors and needs and to access needed services.

6. Parents and caregivers will demonstrate attachment and responsive parenting behaviors.

7. Parents and caregivers will demonstrate ability to accept child’s limitations and recognize child’s or youth’s strengths.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for identifying and referring persons with fetal alcohol syndrome. MMWR. 2005;54(No. RR-11):1.

Gerberding JL, Cordeo J, Floyd RL. Fetal alcohol syndrome: Guidelines for referral and diagnosis. Washington, DC: National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, Centers for Disease Control, Department of Health and Human Services, 2004.

National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. FASD Identification. (website): www.nofas.org/MediaFiles/PDFs/factsheets/identification.pdf Accessed January 10, 2007

National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. FASD Intervention. (website): www.nofas.org/MediaFiles/PDFs/factsheets/intervention.pdf Accessed January 10, 2007

National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome. FASD What school systems should know about affected students. (website): www.nofas.org/MediaFiles/PDFs/factsheets/students%20school.pdf Accessed January 10, 2007

National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome:. FASD What the health care system should know. (website): www.nofas.org/MediaFiles/PDFs/factsheets/healthcare.pdf Accessed January 10, 2007

U.S. Surgeon General. United States Surgeon General releases advisory on alcohol use in pregnancy. (website): www.surgeongeneral.gov/pressreleases/sg02222005. html Accessed January 10, 2007