Chapter 62 Femoral Shaft Fractures: What Is the Best Treatment?

Intramedullary nailing remains the treatment of choice for femoral shaft fractures. However, some situations may direct surgeons to different treatment options. To guide the reader in making choices between these treatment options, we use the Evidence Cycle. This cycle systematically approaches clinical problems using evidence-based medicine.1–4 The Evidence Cycle can be conceptualized to consist of five A’s: assess, ask, acquire, appraise, and apply.

OPTIONS

Our review focuses on the following treatment options: plating or nailing. Specific technical issues that relate to intramedullary nails include the evidence surrounding fracture-table versus freehand reduction techniques, slotted versus solid intramedullary nailing, antegrade versus retrograde intramedullary nailing, trochanteric versus piriformis entry point, reamed versus undreamed nailing, and lastly, static versus dynamic locking of intramedullary nails. Timing of surgery is discussed in Chapter 50.

Our outcomes of interest are nonunion, malunion, including malrotation, and other adverse events. Each clinical question is addressed using a structured PICO (Patients, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) format.3,5

EVIDENCE

Plating or Intramedullary Nailing

Particularly in the patient with multiple injuries, plating was thought to have advantages in preventing brain damage in the patient with head injury.6 Thus, our first question using the PICO format is: In patients with head injury and femoral shaft fracture (P), will plating (I) or intramedullary nailing (C) result in better neurologic outcome (O)? Bhandari and coworkers6 evaluated this question in an observational study. The authors identified 21 patients with severe head injuries treated with a reamed femoral nail for a femoral fracture and 29 comparable patients treated by means of a femoral plate. In their series, severity of the head injury was the strongest predictor for outcome. Nailing was considered a safe procedure that did not worsen outcome, although the authors conclude that a large, sufficiently powered, randomized, controlled trial (RCT) is needed to definitively resolve this controversy6 (grade C).

Bosse and coworkers’7 retrospective study compares data from a trauma center using reamed nailing (I) for acute stabilization of femoral fractures with data from another North American center using plating (C). The rate of adult respiratory distress syndrome (O) in the patients who had a femoral fracture without a thoracic injury did not vary considerably according to whether the fracture had been nailed (118 patients) or plated (114 patients). Equally, the occurrence of adult respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, failure of multiple organs, or mortality for the patients who had a femoral fracture and thoracic injury was comparable regardless of whether reamed nailing (117 patients) or plating (104 patients) had been used. The authors conclude that the use of intramedullary reamed nailing for acute fixation of fractures of the femur in patients with multiple injuries who have a thoracic injury without major comorbidity did not seem to increase the likelihood of development of adult respiratory distress syndrome, pulmonary embolism, failure of multiple organs, pneumonia, or mortality7 (grade C).

Fracture-Table versus Freehand Reduction

After choosing intramedullary nailing as the treatment option for femoral shaft fractures, surgeons have different fracture reduction techniques in their toolbox. Stephen and coworkers8 compared fracture-table (I) with manual traction (C) in femoral intramedullary nailing in a well-designed, sufficiently powered RCT.8 The primary outcome was number of patients with 10 degrees or more malrotation. Also, the authors scored severity of rotational malalignment. Operative procedure time was a secondary outcome. Internal malrotation was exceedingly more frequent when the fracture table had been used: 12 (29%) of the 43 femora were internally rotated by more than 10 degrees compared with 3 (7%) of the 45 reduced with manual traction (P = 0.007). Total procedure time, from the beginning of the patient positioning to the finishing point of the skin closure, was reduced from a mean of 139 minutes (range, 100–212 minutes) when the fracture table was used to a mean of 119 minutes (range, 65–180 minutes) when manual traction was used (P = 0.033). No significant difference was found between the two treatment groups with regard to the number of assistants per case (mean, 2; range, 0–3), fluoroscopy time, other adverse events including femoral leg length discrepancy, or functional condition of the patient at 1-year follow-up8 (grade A).

Slotted versus Solid Intramedullary Nail

After the fracture is manually well reduced and rotationally aligned options for nailing include using either a slotted or a solid nail. One European and one North American study evaluated this issue.9,10 Alho and coauthors10 randomized 22 nonslotted Gross–Kempf nails and 24 slotted AO/ASIF universal femoral nails. Although the nonslotted nails showed higher stiffness than the slotted nails, insertion resulted in splintering of the distal fragment, one resulting in a change of the implant to a condylar plate. Other complications were not implant related. No nonunions were observed in either group.

Cameron and coworkers9 randomized patients with femoral shaft fractures into three groups: 32 were treated with a nonslotted Grosse–Kempf nail, 29 with a Russell–Taylor nail (nonslotted), and 27 with a Synthes nail (slotted). The operation took less time in the Grosse–Kempf nail group. Three proximal fractures could not be locked with the Synthes nail. At follow-up examination, the authors did not find important difference in pain, limp, range of motion, or time to union. On the other hand, the investigators removed fewer Synthes nails to resolve patient reports of pain. Three delayed unions were due to fracture distraction and were not implant related. The authors conclude that all three nails are suitable for the treatment of almost all femoral shaft fractures (grade I).

Antegrade versus Retrograde Nailing

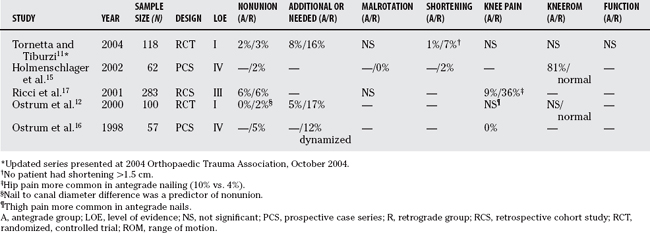

Two studies compared antegrade versus retrograde reamed intramedullary nailing in RCTs with methodologic shortcomings. Tornetta and Tiburzi11 used hospital chart numbers for patient allocation and randomized 38 fractures in the antegrade group and 31 in the retrograde group. A rotational deformity of greater than 10 degrees was seen on computed tomographic rotation studies in 3 of 18 (17%) of the antegrade and in 5 of 15 (33%) of retrograde nailings performed in cases with unstable patterns. Shortening occurred in five unstable fractures in the retrograde group, but in none of such injuries in the antegrade group. In these five patients, shortening averaged 12 mm (5–30 mm). Return to the operating room for acute lengthening and relocking was necessary for a patient with 3 cm of shortening. At union, four patients with retrograde nailing and five with antegrade nailing reported pain in the knee.

Ostrum and coworkers12 compared 44 fractures (7 bilateral) treated with a retrograde nail and 46 (1 bilateral) with an antegrade nail. Discussing fracture results and not patients complicates making inferences when patients with bilateral fractures are compared with patients with single-site fractures.5,13 Knee pain was equal in both groups (4 patients in the antegrade group; 5 patients in the retrograde group), but hip and thigh pain was in the majority in the antegrade-treated group (10 patients in the antegrade group; 2 patients in the retrograde group; P = 0.0108). Finally, three retrospective case series described this issue.14–17

Table 62-1 provides detailed information on the available data. Despite the potential for complications, most concerns have been unrealized in recent comparisons between antegrade and retrograde intramedullary nails in patients with femoral shaft fractures (see Table 62-1). In brief, retrograde nails achieve equal union rates and function at the expense of an increased need for nail dynamization. Shortening occurs at a greater rate with retrograde nail insertion but is seldom clinically significant (<1.5 cm). Thigh and hip pain, a common occurrence in antegrade nails, is significantly reduced with retrograde nail insertion. In conclusion, surgeons with experience in retrograde nailing techniques can achieve outcomes similar to those of antegrade nailing techniques. Retrograde nailing may be particularly useful in patients with multiple ipsilateral injuries and in obese patients. Based on our review, both antegrade and retrograde procedures can have acceptable results (grade B).

Trochanteric versus Piriformis Entry Point

Based on a prospective cohort study comparing 38 patients in the trochanteric starting point group with 53 in the piriformis fossa entry point, Ricci and coworkers18 found reduced fluoroscopy time using a trochanteric starting point and similar overall outcome (grade C).

Reamed versus Unreamed Nailing

The controversy surrounding reamed versus unreamed nailing is evaluated in several RCTs. Bhandari and coworkers19 performed a systematic review published in 2000 comparing reamed versus unreamed nailing of lower extremity long bone fractures. Since this publication, new RCTs and a new systematic review have become available.20

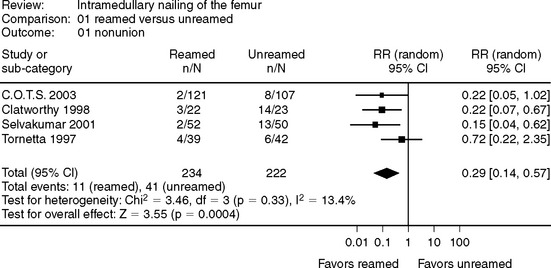

Key outcomes of interest in these studies are delayed or nonunion and post-traumatic acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Pooling the data of four currently published studies showed a relative risk of 0.29 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.14–0.57) for delayed or nonunion favoring reamed nails (Fig. 62-1).21–24 Translated into number needed to treat (NNT) equals 7 (95% CI, 5–12); that is, with every 7 patients treated with a reamed nail, 1 delayed or nonunion result will be prevented.

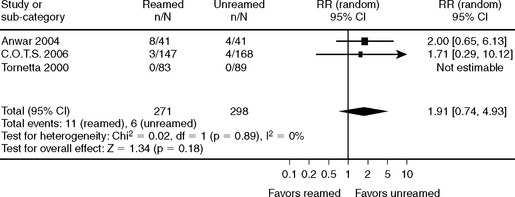

The relative risk for ARDS in patients treated with a reamed nail was 1.91 (95% CI, 0.74–4.93) (Fig. 62-2).21,24, 25 The CIs crossing 1 indicate a nonsignificant result.

FIGURE 62-2 Pooled results reamed versus undreamed femoral nailing in preventing acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).24,25, 29 CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk.

Data from Anwar IA, Battistella FD, Neiman R, Olson SA, Chapman MW, and Moehring HD: Femur fractures and lung complications: a prospective randomized study of reaming. Clin Orthop 71-76, 2004; and Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society: Nonunion following intramedullary nailing of the femur with and without reaming. Results of a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 85-A: 2093-2096, 2003.

Femoral shaft fractures can be treated safely using reamed intramedullary nails preventing delayed or nonunions without strong evidence for increasing risk for ARDS (grade B).

Static or Dynamic Locking

After the nail is inserted, static or dynamic locking of the nail is possible. One small RCT with methodologic shortcomings did not show a difference in union rates between static and dynamic locking; however, the authors did observe a trend to earlier union in the dynamically locked group.26 Of the 26 femoral fractures in the dynamized group, union occurred between 13 and 28 weeks (average, 19.2 weeks) in 25 of 26 patients. Union rate was 96.2% in the dynamized group. Of the 24 patients with femoral fractures in the static group, union was achieved in 23 between 16 and 30 weeks (average, 23.45 weeks); union rate was 95.8%.

Conflicting information comes from a larger observational study comparing data from two Italian hospitals.27 Time to union was significantly shorter in the 104 patients treated in the static group (103 days) compared with the 75 patients treated in the dynamized group (126 days)27 (grade I conflicting data). Biomechanical data suggest that immediate weight bearing as tolerated is safe after static locking, even in comminuted fractures.28 Dynamic locking of comminuted shaft fractures should be avoided because it would preclude immediate weight bearing without incurring shortening of the fracture.

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Patients with Multiple Injuries

Based on our review, our recommendations are as follows:

Table 62-2 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of femoral shaft fractures.

| RECOMMENDATIONS | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

1 Guyatt GH, Rennie D, The Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature, A Manual for Evidence-Based Clinical Practice. Chicago: AMA Press, 2002.

2 Hayward R. Centre for Health Evidence on line. Available at: http://www.cche.net/.

3 Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123:A12-A13.

4 Sackett DL, Straus SE, Richardson WS, et al. Evidence-Based Medicine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

5 Poolman RW, Kerkhoffs GM, Struijs PA, et al. Don’t be misled by the orthopedic literature: Tips for critical appraisal. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:162-171.

6 Bhandari M, Guyatt GH, Khera V, et al. Operative management of lower extremity fractures in patients with head injuries. Clin Orthop. 2003:187-198.

7 Bosse MJ, MacKenzie EJ, Riemer BL, et al. Adult respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, and mortality following thoracic injury and a femoral fracture treated either with intramedullary nailing with reaming or with a plate. A comparative study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:799-809.

8 Stephen DJG, Kreder HJ, Schemitsch EH, et al. Femoral intramedullary nailing: Comparison of fracture-table and manual traction: A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1514-1521.

9 Cameron CD, Meek RN, Blachut PA, et al. Intramedullary nailing of the femoral shaft: A prospective, randomized study. J Orthop Trauma. 1992;6:448-451.

10 Alho A, Moen O, Husby T, et al. Slotted versus non-slotted locked intramedullary nailing for femoral shaft fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1992;111:91-95.

11 Tornetta PIII, Tiburzi D. Antegrade or retrograde reamed femoral nailing. A prospective, randomised trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:652-654.

12 Ostrum RF, Agarwal A, Lakatos R, Poka A. Prospective comparison of retrograde and antegrade femoral intramedullary nailing. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:496-501.

13 Bryant D, Havey TC, Roberts R, Guyatt G. How many patients? How many limbs? Analysis of patients or limbs in the orthopaedic literature: A systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:41-45.

14 Blum J, Janzing H, Gahr R, et al. Clinical performance of a new medullary humeral nail: Antegrade versus retrograde insertion. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:342-349.

15 Holmenschlager F, Piatek S, Halm JP, Winckler S. [Retrograde intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures. A prospective study]. Unfallchirurg. 2002;105:1100-1108.

16 Ostrum RF, DiCicco J, Lakatos R, Poka A. Retrograde intramedullary nailing of femoral diaphyseal fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1998;12:464-468.

17 Ricci WM, Bellabarba C, Evanoff B, et al. Retrograde versus antegrade nailing of femoral shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:161-169.

18 Ricci WM, Schwappach J, Tucker M, et al. Trochanteric versus piriformis entry portal for the treatment of femoral shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:663-667.

19 Bhandari M, Guyatt GH, Tong D, et al. Reamed versus nonreamed intramedullary nailing of lower extremity long bone fractures: A systematic overview and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:2-9.

20 Forster MC, Aster AS, Ahmed S. Reaming during anterograde femoral nailing: Is it worth it? Injury. 2005;36:445-449.

21 Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma. Nonunion following intramedullary nailing of the femur with and without reaming. Results of a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:2093-2096.

22 Clatworthy MG, Clark DI, Gray DH, Hardy AE. Reamed versus unreamed femoral nails. A randomised, prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:485-489.

23 Selvakumar K, Saw KY, Fathima M. Comparison study between reamed and unreamed nailing of closed femoral fractures. Med J Malaysia. 2001;56(suppl D):24-28.

24 Tornetta PIII, Tiburzi D. Reamed versus nonreamed anterograde femoral nailing. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:15-19.

25 Anwar IA, Battistella FD, Neiman R, et al. Femur fractures and lung complications: A prospective randomized study of reaming. Clin Orthop. 2004;422:71-76.

26 Basumallick MN, Bandopadhyay A. Effect of dynamization in open interlocking nailing of femoral fractures. A prospective randomized comparative study of 50 cases with a 2-year follow-up. Acta Orthop Belg. 2002;68:42-48.

27 Tigani D, Fravisini M, Stagni C, et al. Interlocking nail for femoral shaft fractures: Is dynamization always necessary? Int Orthop. 2005;29:101-104.

28 Brumbach, et al. Immediate weight-bearing after treatment of a comminuted fracture of the femoral shaft with a statically locked intramedullary nail. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1538-1544.

29 Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society. Reamed versus unreamed intramedullary nailing of the femur: Comparison of the rate of ARDS in multiple injured patients. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20(6):384-387.