CHAPTER 77 Female reproductive system

The female reproductive system consists of the lower genital tract (vulva and vagina) and the upper tract (uterus and cervix with associated uterine (Fallopian) tubes and ovaries).

LOWER GENITAL TRACT

VULVA

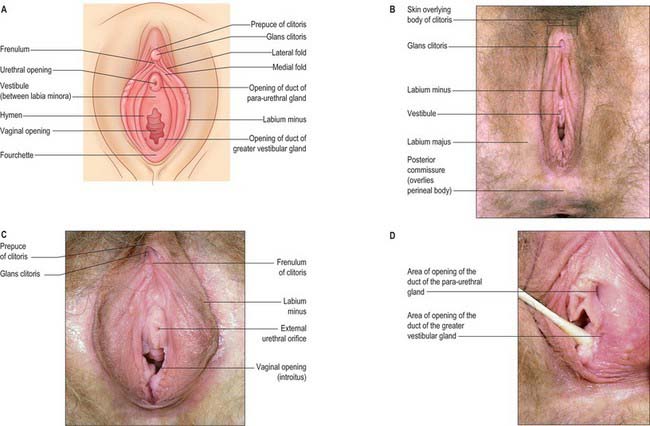

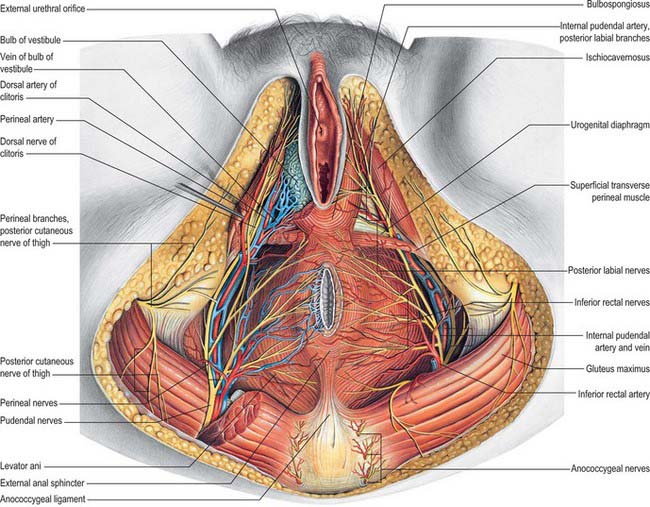

The female external genitalia or vulva include the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vestibule, vestibular bulb and the greater vestibular glands (Fig. 77.1A–D).

Labia majora

The labia majora are two prominent, longitudinal folds of skin that extend back from the mons pubis to the perineum (Fig. 77.1B). They form the lateral boundaries of the vulva. Each labium has an external, pigmented surface covered with hairs and a smooth, pink internal surface with large sebaceous follicles. Between these surfaces there is loose connective and adipose tissue, intermixed with smooth muscle (resembling the scrotal dartos muscle), vessels, nerves and glands. The uterine round ligament may end in the adipose tissue and skin in the anterior part of the labium. A persistent processus vaginalis and congenital inguinal hernia may also reach a labium. The labia are thicker anteriorly, where they join to form the anterior commissure. Posteriorly they do not join, but instead merge into neighbouring skin, ending near and almost parallel to each other. The connecting skin between them posteriorly forms a ridge, the posterior commissure, that overlies the perineal body and is the posterior limit of the vulva. The distance between this and the anus is 2.5–3 cm thick and is termed the ‘gynaecological’ perineum.

Labia minora

The labia minora are two small cutaneous folds, devoid of fat, that lie between the labia majora. They extend from the clitoris obliquely down, laterally and back, flanking the vaginal orifice. Anteriorly, each labium minus bifurcates. The upper layer of each side passes above the clitoris to form a fold, the hood or prepuce, which overhangs the glans of the clitoris. The lower layer of each side passes below the clitoris to form the frenulum of the clitoris (Fig. 77.1A,C). Sebaceous follicles are numerous on the apposed labial surfaces. Sometimes an extra labial fold (labium tertium) is found on one or both sides between the labia minora and majora.

Vestibule

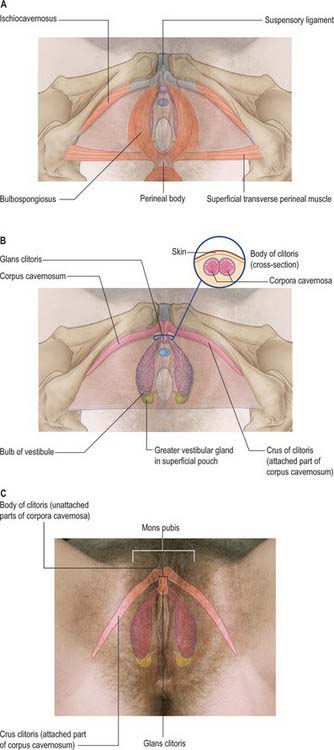

Bulbs of the vestibule

The bulbs of the vestibule lie on each side of the vestibule. They are two elongated masses of erectile tissue, 3 cm long, which flank the vaginal orifice and unite anterior to it by a narrow commissura bulborum (pars intermedia). Their posterior ends are expanded and are in contact with the greater vestibular glands. Their anterior ends taper and are joined by a commissure and also to the clitoris by two slender bands of erectile tissue. Their deep surfaces contact the inferior aspect of the urogenital diaphragm, and superficially each is covered by bulbospongiosus posteriorly (Fig. 77.2A–C).

Greater vestibular glands (Bartholin’s glands)

The greater vestibular glands are homologues of the male bulbourethral glands. They consist of two small, round or oval, reddish-yellow bodies that flank the vaginal orifice, in contact with, and often overlapped by, the posterior end of the vestibular bulb. Each opens into the postero-lateral part of the vestibule by a 2 cm duct, situated in the groove between the hymen and the labium minus (Fig. 77.1D). The glands are composed of tubulo-acinar tissue. The secretory cells are columnar and secrete a clear or whitish mucus with lubricant properties. They are stimulated by sexual arousal.

Clitoris

The clitoris is an erectile structure partially enclosed by the anterior bifurcated ends of the labia minora. It has a root, a body, and a glans. The body can be palpated through the skin. It contains two corpora cavernosa, composed of erectile tissue and enclosed in dense fibrous tissue, and separated medially by an incomplete fibrous pectiniform septum. The fibrous tissue forms a suspensory ligament that is attached superiorly to the pubic symphysis. Each corpus cavernosum is attached to its ischiopubic ramus by a crus that extends from the root of the clitoris. The glans clitoris is a small round tubercle of spongy erectile tissue at the end of the body and connected to the bulbs of the vestibule by thin bands of erectile tissue. It is exposed between the anterior ends of the labia minora. Its epithelium has high cutaneous sensitivity, important in sexual responses (Fig. 77.2).

Vascular supply and lymphatic drainage of the vulva

Arteries

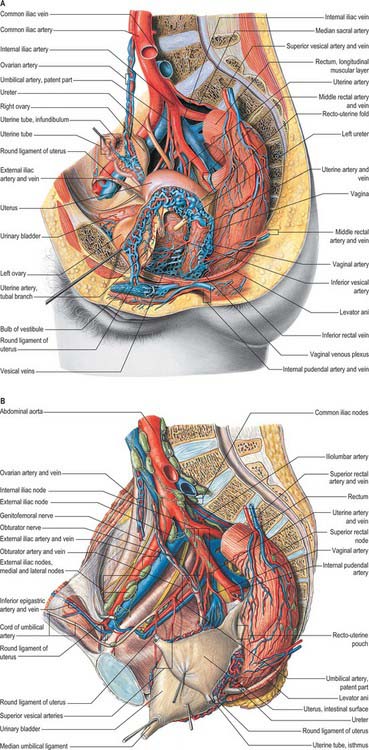

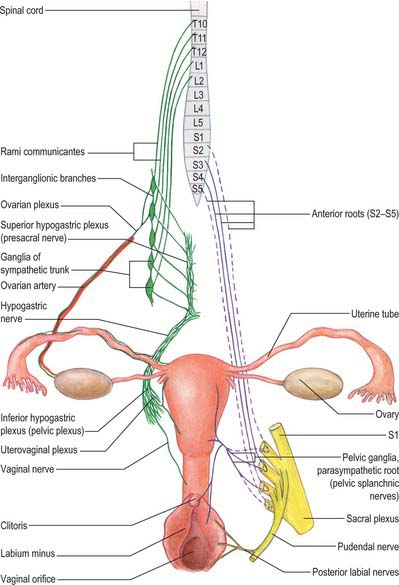

The arterial blood supply of the female external genitalia is derived from the superficial and deep external pudendal branches of the femoral artery and the internal pudendal artery on each side (Fig. 77.3A).

Veins

Venous drainage of the vulval skin is via external pudendal veins to the long saphenous vein. Venous drainage of the clitoris is via deep dorsal veins to the internal pudendal vein and superficial dorsal veins to the external pudendal and long saphenous veins (Fig. 77.3A).

Lymphatic drainage

A meshwork of connecting vessels join to form three or four collecting trunks around the mons pubis which drain to superficial inguinal nodes lying on the cribriform fascia covering the femoral artery and vein; these nodes drain through the cribriform fascia to the deep inguinal nodes lying medial to the femoral vein. The deep inguinal nodes drain via the femoral canal to the pelvic nodes. The last of the deep inguinal nodes lies under the inguinal ligament within the femoral canal and is often called Cloquet’s node. Lymph vessels in the perineum and lower part of the labia majora drain to the rectal lymphatic plexus. Lymph vessels from the clitoris and labia minora drain to deep inguinal nodes and direct clitoral efferents may pass to the internal iliac nodes (Fig. 77.3B).

VAGINA

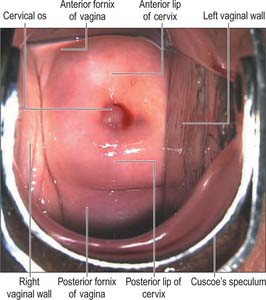

The vagina is a fibromuscular tube lined by non-keratinized stratified epithelium. It extends from the vestibule (the opening between the labia minora) to the uterus. The upper end of the vagina surrounds the vaginal projection of the uterine cervix. The annular recess between the cervix and vagina is the fornix: the different parts of this recess are given separate names, i.e. anterior, posterior and right and left lateral, but they are continuous (Fig. 77.6).

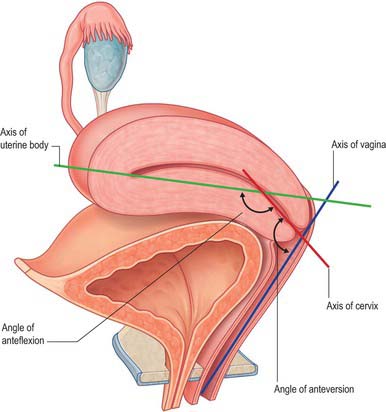

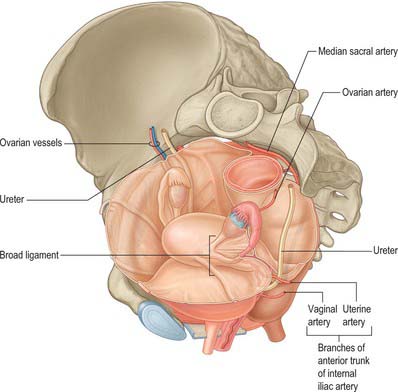

The vagina ascends posteriorly and superiorly at an angle of over 90° to the uterine axis: this angle varies with the contents of the bladder and rectum. The width of the vagina increases as it ascends. Above the level of the hymen, the inner surfaces of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls are ordinarily in contact with each other forming a transverse slit. The vaginal mucosa is attached to the uterine cervix higher on the posterior cervical wall than on the anterior: the anterior wall is approximately 7.5 cm long and the posterior wall is approximately 9 cm long. The anterior wall of the vagina is related to the base of the bladder in its middle and upper portions and to the urethra (which is embedded in it) inferiorly. The posterior wall is covered by peritoneum in its upper quarter. It is separated from the rectum by the recto-uterine pouch superiorly, and by moderately loose connective tissue (Denonvillier’s fascia) in its middle half. In its lower quarter it is separated from the anal canal by the musculofibrous perineal body. Laterally are levator ani and pelvic fascia (see Fig. 75.1A). As the ureters pass anteromedially to reach the fundus of the bladder, they pass close to the lateral fornices. As they enter the bladder the ureters are usually anterior to the vagina, and at this point, each ureter is crossed transversely by a uterine artery (Fig. 77.7).

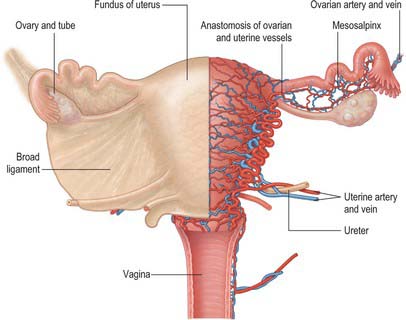

Fig. 77.7 Relationship of the ureter to the uterine and vaginal arteries.

(From Drake, Vogl and Mitchell 2005.)

Remnants of the duct of Gartner (embryologically the caudal end of the mesonephric duct) (see Ch. 78), are occasionally seen protruding through the lateral fornices or lateral parts of the vagina; these can cause cysts (Gartner’s cysts).

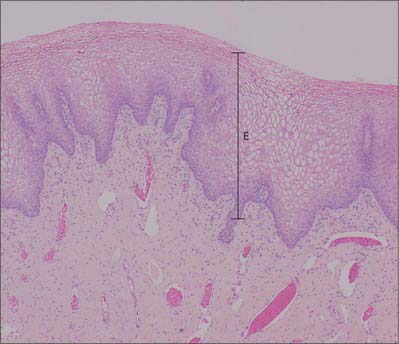

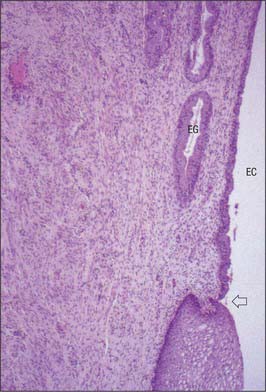

Microstructure

The vagina has an inner mucosal and an external muscular layer. The mucosa adheres firmly to the muscular layer. There are two median longitudinal ridges on its epithelial surface, one anterior and the other posterior. Numerous transverse bilateral rugae extend from these vaginal columns. They are divided by sulci of variable depth, giving an appearance of conical papillae, which are most numerous on the posterior wall and near the orifice, and which are especially well developed before parturition. The epithelium is non-keratinized, stratified, squamous similar to, and continuous with, that of the ectocervix. After puberty it thickens and its superficial cells accumulate glycogen, which gives them a clear appearance in histological preparations.

The vaginal epithelium does not change markedly during the menstrual cycle, but its glycogen content increases after ovulation and then diminishes towards the end of the cycle. Natural vaginal bacteria, particularly Lactobacillus acidophilus, break down glycogen in the desquamated cellular debris to lactic acid. This produces a highly acidic (pH 3) environment, which inhibits the growth of most other microorganisms. The amount of glycogen is less before puberty and after the menopause, when vaginal infections are more common. There are no mucous glands, but a fluid transudate from the lamina propria and mucus from the cervical glands lubricate the vagina (Fig. 77.8). The muscular layers are composed of smooth muscle and consist of a thick outer longitudinal and an inner circular layer. The two layers are not distinct but connected by oblique interlacing fibres. Longitudinal fibres are continuous with the superficial muscle fibres of the uterus. Half way along the vagina is a U-shaped muscular sling, called the pubo-vaginalis. The lower vagina is also surrounded by the skeletal muscle fibres of bulbospongiosus. A layer of loose connective tissue, containing extensive vascular plexuses, surrounds the muscle layers.

UPPER GENITAL TRACT

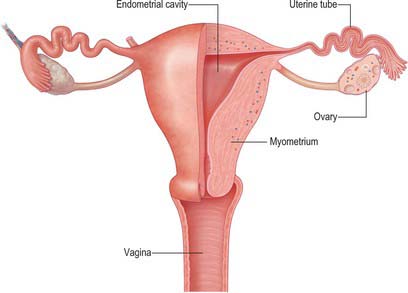

UTERUS

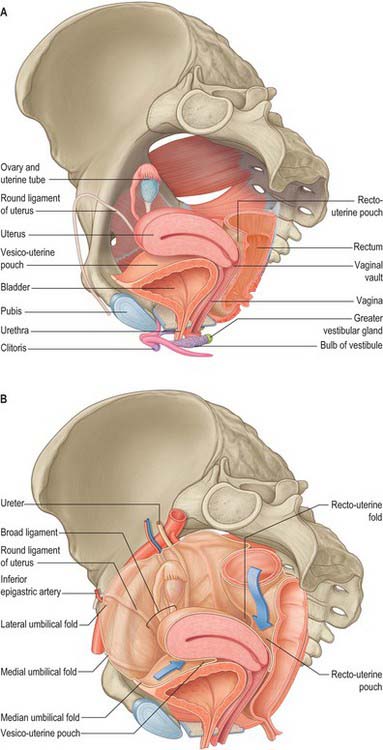

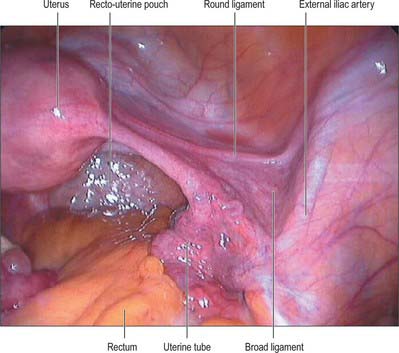

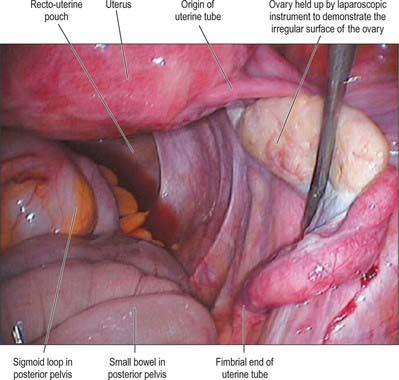

The uterus is a thick-walled, muscular organ situated in the pelvis between the urinary bladder and the rectum (Figs 77.9–77.11). It lies posterior to the bladder and uterovesical space and anterior to the rectum and recto-uterine pouch: it is mobile, which means that its position varies with distension of the bladder and rectum. The broad ligaments are lateral.

The uterus is divided into two main regions: the body of the uterus (corpus uteri) forms the upper two-thirds, and the cervix (cervix uteri) forms the lower third. In the adult nulliparous state the cervix tilts forwards relative to the axis of the vagina (anteversion), and the body of the uterus tilts forward relative to the cervix (anteflexion) (Fig. 77.12). In 10 to 15% of women the whole uterus leans backwards at an angle to the vagina and is said to be retroverted. A uterus that angles backwards on the cervix is described as retroflexed.

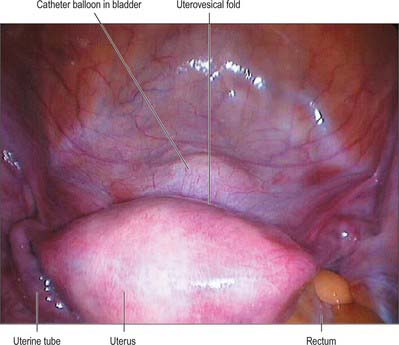

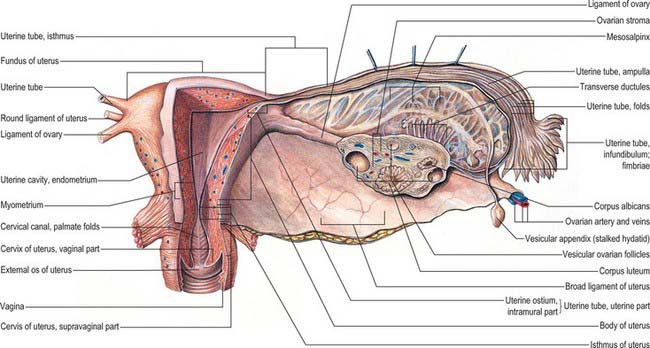

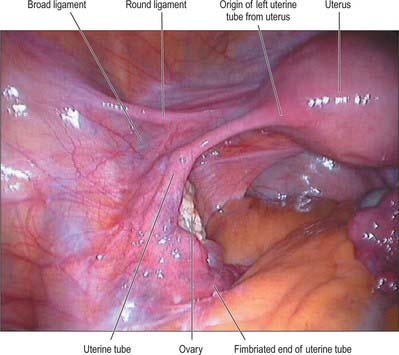

Body

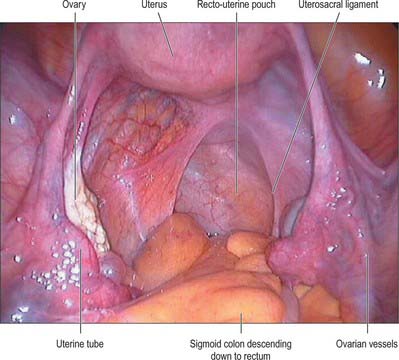

The body of the uterus is pear shaped and extends from the fundus superiorly to the cervix inferiorly. Near its upper end, the uterine tubes enter the uterus on both sides at the uterine cornua. Inferoanterior to each cornu is the round ligament and inferoposterior is the ovarian ligament. The dome-like fundus is superior to the entry points of the uterine tubes and covered by peritoneum which is continuous with that of neighbouring surfaces. The fundus is in contact with coils of small intestine and occasionally by distended sigmoid colon. The lateral margins of the body are convex, and on each side their peritoneum is reflected laterally to form the broad ligament, which extends as a flat sheet to the pelvic wall (Fig. 77.13). The anterior surface of the uterine body is covered by peritoneum which is reflected onto the bladder at the uterovesical fold (Fig. 77.14). This normally occurs at the level of the internal os, the most inferior margin of the body of the uterus. The vesico-uterine pouch between the bladder and uterus is obliterated when the bladder is distended, but may be occupied by small intestine when the bladder is empty. The posterior surface of the uterus is convex transversely. Its peritoneal covering continues down to the cervix and upper vagina and is then reflected back to the rectum along the surface of the recto-uterine pouch (of Douglas), which lies posterior to the uterus (Fig. 77.15). The sigmoid colon and occasionally the terminal ileum lie posterior to the uterus.

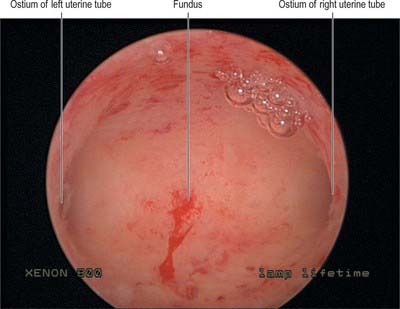

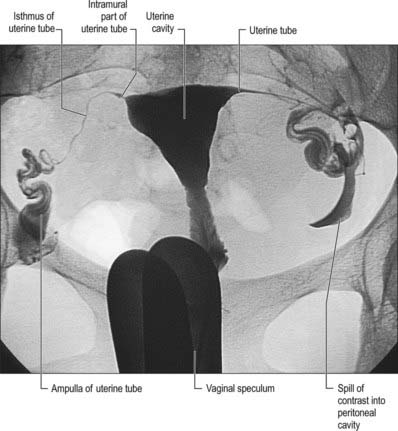

The cavity of the uterine body usually measures 6 cm from the external os of the cervix to the wall of the fundus and is flat in its anteroposterior plane. In coronal section, it is triangular, broad above where the two uterine tubes join the uterus, and narrow below at the internal os of the cervix (Fig. 77.16).

Cervix

The adult, non-pregnant cervix is narrower and more cylindrical than the body of the uterus and is typically 2.5 cm long. The upper end communicates with the uterine body via the internal os and the lower end opens into the vagina at the external os. In nulliparous women, the external os is usually a circular aperture, whereas after childbirth it is a transverse slit. Two longitudinal ridges, one each on its anterior and posterior walls, give off small oblique palmate folds that ascend laterally like the branches of a tree (arbor vitae uteri): the folds on opposing walls interdigitate to close the canal. The narrower isthmus forms the upper third of the cervix. Although unaffected in the first month of pregnancy, it is gradually taken up into the uterine body during the second month to form the ‘lower uterine segment’ (see below). In non-pregnant women the isthmus undergoes menstrual changes, although these are less pronounced than those occurring in the uterine body. The external end of the cervix enters the upper end of the vagina, thereby dividing the cervix into supravaginal and vaginal parts. The supravaginal part is separated anteriorly from the bladder by cellular connective tissue, the parametrium, which also passes to the sides of the cervix and laterally between the two layers of the broad ligaments.

Pelvic ligaments and peritoneal folds

Peritoneal folds

Uterovesical and rectovaginal folds

The anterior or uterovesical fold consists of peritoneum reflected onto the bladder from the uterus at the junction of its cervix and body. The posterior or rectovaginal fold consists of peritoneum reflected from the posterior vaginal fornix on to the front of the rectum, thereby create the deep recto-uterine pouch of Douglas. The pouch of Douglas is bounded anteriorly by the uterus, supravaginal cervix and posterior vaginal fornix, posteriorly by the rectum and laterally by the uterosacral ligaments.

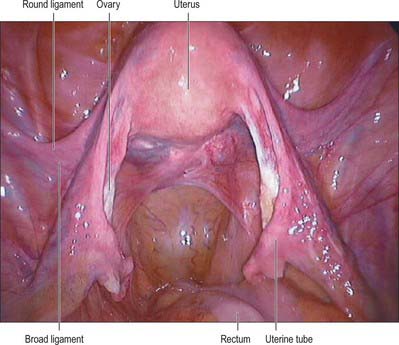

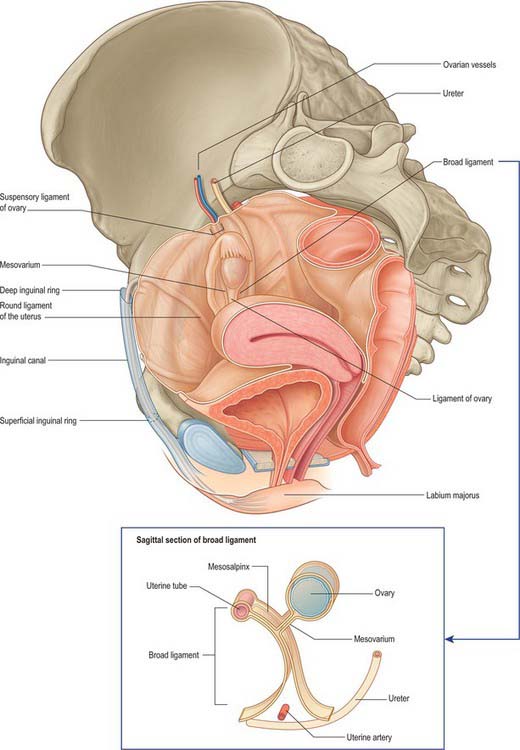

Broad ligament

The lateral folds or broad ligaments extend on each side from the uterus to the lateral pelvic walls, where they become continuous with the peritoneum covering those walls (Figs 77.17, 77.18). The upper border is free and the lower border is continuous with the peritoneum over the bladder, rectum and pelvic side-wall. The borders are continuous with each other at the free edge via the uterine fundus and diverge below near the superior surfaces of levatores ani. A uterine tube lies in the upper free border on either side. The broad ligament is divided into an upper mesosalpinx, a posterior mesovarium and an inferior mesometrium.

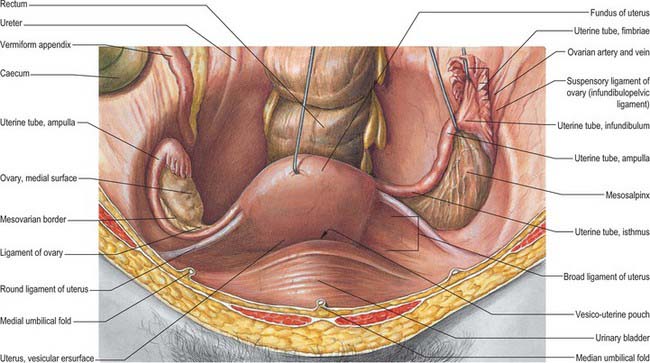

Fig. 77.17 Pelvic peritoneal reflections, demonstrating the broad ligament and its contents.

(From Drake, Vogl and Mitchell 2005.)

Fig. 77.18 Ovaries and broad ligament, superior view with the uterus lifted away from the bladder.

(From Sobotta 2006.)

Mesosalpinx

The mesosalpinx is attached above to the uterine tube and posteroinferiorly to the mesovarium. Superior and laterally it is attached to the suspensory ligament of the ovary and medially it is attached to the ovarian ligament. The fimbria of the tubal infundibulum projects from its free lateral end. Between the ovary and uterine tube the mesosalpinx contains vascular anastomoses between the uterine and ovarian vessels, the epoophoron, and the paroophoron (Fig. 77.19). The mesovarium projects from the posterior aspect of the broad ligament, of which it is the smaller part. It is attached to the hilum of the ovary and carries vessels and nerves to the ovary.

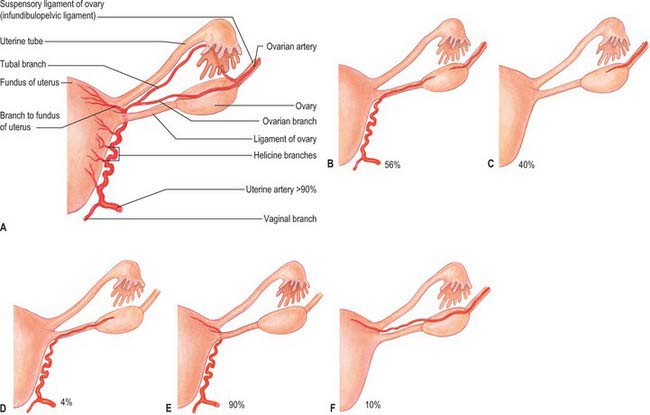

Mesometrium

The mesometrium is the largest part of the broad ligament, and extends from the pelvic floor to the ovarian ligament and uterine body. The uterine artery passes between its two peritoneal layers typically 1.5 cm lateral to the cervix: it crosses the ureter shortly after its origin from the internal iliac artery and gives off a branch that passes superiorly to the uterine tube, where it anastomoses with the ovarian artery (Fig. 77.19). Between the pyramid formed by the infundibulum of the tube, the upper pole of the ovary, and the lateral pelvic wall, the mesometrium contains the ovarian vessels and nerves lying within the fibrous suspensory ligament of the ovary (infundibulopelvic ligament). This ligament continues laterally over the external iliac vessels as a distinct fold. The mesometrium also encloses the proximal part of the round ligament of the uterus, as well as smooth muscle and loose connective tissue.

Ligaments of the pelvis

Uterosacral, transverse cervical and pubocervical ligaments

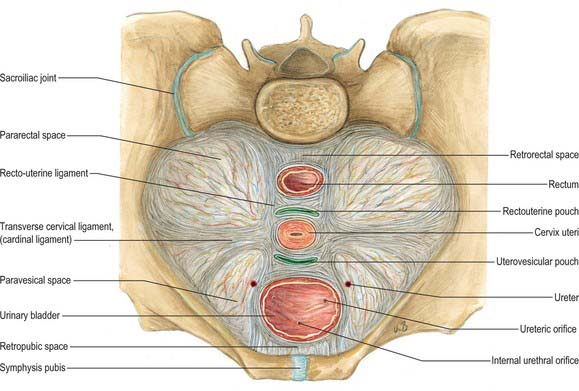

The uterosacral ligaments are recto-uterine folds and contain fibrous tissue and smooth muscle (Fig. 77.18). They pass back from the cervix and uterine body on both sides of the rectum, and they are attached to the front of the sacrum. The ligaments can be palpated laterally on rectal examination. On vaginal examination they can be felt as thick bands of tissue passing downwards on both sides of the posterior fornix. The transverse cervical ligaments (cardinal ligaments, ligaments of Mackenrodt) (Fig. 77.20) extend from the side of the cervix and lateral fornix of the vagina to attach extensively on the pelvic wall. At the level of the cervix, some fibres interdigitate with fibres of the uterosacral ligaments. They are continuous with the fibrous tissue around the lower parts of the ureters and pelvic blood vessels. Fibres of the pubocervical ligament pass forward from the anterior aspect of the cervix and upper vagina to diverge around the urethra (Fig. 77.20). These fibres attach to the posterior aspect of the pubic bones.

Fig. 77.20 Supporting ligaments of the pelvis showing the transverse cervical ligaments.

(From Sobotta 2006.)

While the uterosacral and transverse cervical ligaments may act in varying measure as mechanical supports of the uterus, levatores ani and coccygei, the urogenital diaphragm and the perineal body appear at least as important in this respect. There has been renewed interest in the supporting structures of the pelvis, and the subject has been reviewed in detail by Delancey (2000).

Vascular supply and lymphatic drainage

Arteries

The arterial supply to the uterus comes from the uterine artery (Fig. 77.21). This arises as a branch of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery. From its origin, the uterine artery crosses the ureter anteriorly in the broad ligament before branching as it reaches the uterus at the level of the cervico-uterine junction. One major branch ascends the uterus tortuously within the broad ligament until it reaches the region of the ovarian hilum, where it anastomoses with branches of the ovarian artery. Another branch descends to supply the cervix and anastomoses with branches of the vaginal artery to form two median longitudinal vessels, the azygos arteries of the vagina, which descend anterior and posterior to the vagina. Although there are anastomoses with the ovarian and vaginal arteries, the dominance of the uterine artery is indicated by its marked hypertrophy during pregnancy.

Veins

The uterine veins extend laterally in the broad ligaments, running adjacent to the arteries and passing over the ureters. They drain into the internal iliac veins (see Fig. 77.30). The uterine venous plexus anastomoses with the vaginal and ovarian venous plexuses.

Microstructure

Body of the uterus

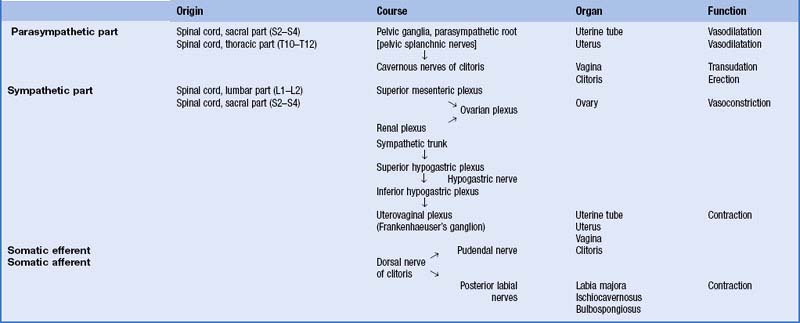

The uterus is composed of three main layers. From its lumen outwards these are the endometrium (mucosa), myometrium (smooth muscle layer) and serosa (or adventitia) (Fig. 77.22).

Cervix uteri

The cervix (Figs 77.23, 77.24) consists of fibroelastic connective tissue and contains relatively little smooth muscle. The elastin component of the cervical stroma is essential to the stretching capacity of the cervix during childbirth. The cervical canal is lined by a deeply folded mucosa with a surface epithelium of columnar mucous cells. There are branched tubular glands present amongst the mucosa, which are lined by a similar secretory epithelium. The glands extend obliquely upwards and outwards from the canal. They secrete clear, alkaline mucus, which is relatively viscous except at the midpoint of the menstrual cycle, when it becomes more copious and less viscous to encourage the passage of sperm. At the vaginal end of the cervix, the aperture of a gland may block and it then fills with mucus to form a Nabothian follicle (or cyst). None of the mucosa is shed during menstruation and so, unlike the body of the uterus, it is not divided into functional and basal layers and lacks spiral arteries. The surface of the intravaginal part of the cervix (ectocervix) is covered by non-keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium, which contains glycogen.

The squamocolumnar junction, where the columnar secretory epithelium of the endocervical canal meets the stratified squamous covering of the ectocervix, is located at the external os before puberty. As oestrogen levels rise during puberty, the cervical os opens, exposing the endocervical columnar epithelium onto the ectocervix. This area of columnar cells on the ectocervix forms an area that is red and raw in appearance called an ectropion (cervical erosion). It is then exposed to the acidic environment of the vagina and through a process of squamous metaplasia transforms into stratified squamous epithelium. This area is thus known as the ‘transformation zone’. Other hyperoestrogenic states such as pregnancy and the use of oral contraceptive pills can also result in an ectropion. This area is the most usual site of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) that may progress to malignancy. In postmenopausal women, the squamo-columnar junction recedes into the endocervical canal (Fig. 77.23).

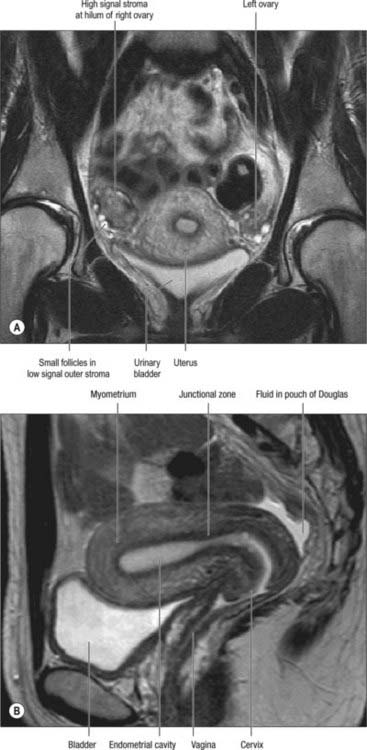

Magnetic resonance imaging of the uterus

On T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the uterus (Fig. 77.25A,B) displays a zonal anatomy, with three distinct zones: the endometrium; junctional zone; and myometrium. The endometrium and uterine cavity appear as a high-signal stripe; the thickness varies with the stage of the menstrual cycle. In the early proliferative phase it measures up to 5 mm, and widens to up to 1 cm in the mid-secretory phase. A band of low signal, the junctional zone, borders the endometrium. It represents the inner myometrium, which blends with the low-signal band of fibrous cervical stroma at the level of the internal os. The junctional zone appears low signal because the cells of the myometrium have low water content when compared to those of the outer myometrium. The junctional zone is of constant thickness and signal throughout the menstrual cycle, and usually measures 5 mm. The outer myometrium is of medium signal intensity in the proliferative phase, and of high signal intensity in the mid-secretory phase as a result of the increased vascularity and prominence of the arcuate vessels.

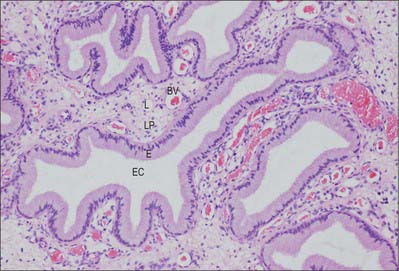

UTERINE (FALLOPIAN) TUBES

The uterine tubes (Fig. 77.26) are attached to the upper part of the body of the uterus and their ostia open into the uterine cavity (Fig. 77.27). The medial opening of the tube (the uterine os) is located at the superior angle of the uterine cavity. The tube passes laterally and superiorly and consists of four main parts: intramural, isthmus, ampulla, fimbria. The intramural part is 0.7 mm wide, 1 cm long, and lies within the myometrium. It is continuous laterally with the isthmus, which is 1–5 mm wide and 3 cm long, and is rounded, muscular and firm. The isthmus is continuous laterally with the ampulla, the widest portion of the tube with a maximum luminal diameter of 1 cm. The ampulla is 5 cm long and has a thin wall and a tortuously folded luminal surface. Typically, fertilization takes place in its lumen. The ampulla opens into the trumpet-shaped infundibulum at the abdominal os. Fimbriae, numerous mucosal finger-like folds, 1 mm wide, are attached to the ends of the infundibulum and extend from its inner circumference beyond the muscular wall of the tube. One of these, the ovarian fimbria, is longer and more deeply grooved than the others, and is typically applied to the tubal pole of the ovary. At the time of ovulation, the fimbriae swell and extend as a result of engorgement of the vessels in the lamina propria, which aids capture of the released oocyte. All fimbriae are covered, like the mucosal lining throughout the tube, by a ciliated epithelium whose cilia beat towards the ampulla.

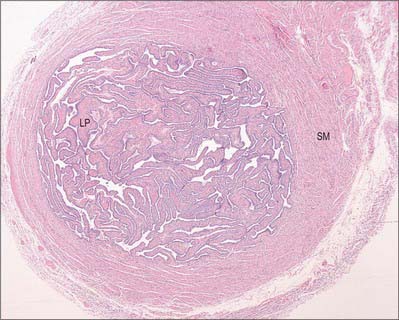

Microstructure

The walls of the uterine tubes show typical visceral mucosal, muscular and serosal layers (Fig. 77.28). The mucosa is thrown into longitudinal folds, which are most pronounced distally at the infundibulum and decrease to shallow bulges in the intrauterine (intramural) portion. The mucosa is lined by a single-layered, tall, columnar epithelium, which contains mainly ciliated cells and secretory (peg) cells (so-called because they project into the lumen further than their ciliated neighbours), and occasional intraepithelial lymphocytes. In the tube, ciliated cells predominate distally and secretory cells proximally. Their activities vary with the stage in the menstrual cycle and with age. Secretory cells are most active around the time of ovulation. Their secretions include nutrients for the gametes and aid capacitation of the spermatozoa. Ciliated cells increase in height and develop more cilia in the oestrogenic first half of the menstrual cycle. Their cilia waft the oocyte from the open-ended infundibulum towards the uterus in fluids secreted by the peg cells. The epithelium regresses in height towards the end of the cycle and postmenopausally, when ciliated cells are reduced in number.

OVARIES

In the adult non-pregnant state, the ovaries lie on each side of the uterus close to the lateral pelvic wall, suspended in the pelvic cavity by a double fold of peritoneum, the mesovarium, which is attached to the upper limit of the posterior aspect of the broad uterine ligament. They are dull white in colour and consist of dense fibrous tissue in which ova are embedded. Before regular ovulation begins they have a smooth surface, but thereafter their surfaces are distorted by scarring that follows the degeneration of successive corpora lutea (Fig. 77.29). Their average dimensions are 4 × 2 × 3 cm in reproductively mature women; they more than double their size during pregnancy. In the neonate, their dimensions are 1.3 × 0.6 × 0.4 cm. Prior to the first menstrual period (menarche) the ovaries are about a third of the normal reproductive adult size; they gradually increase in size with body growth. After the menopause, the average size of the ovary reduces to 2.0 × 1.5 × 0.5 cm and further to 1.5 × 0.75 × 0.5 cm in late menopause.

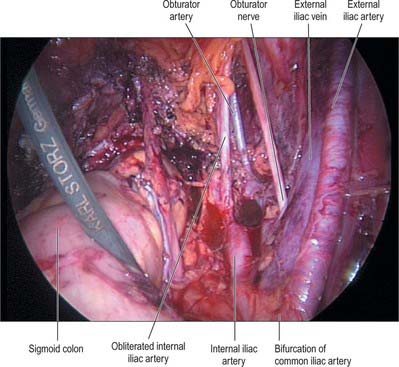

The lateral surface of the ovary contacts parietal peritoneum in the ovarian fossa. Behind the ovarian fossa are retroperitoneal structures, including the ureter, internal iliac vessels, obturator vessels and nerve, and the origin of the uterine artery (Fig. 77.30). The medial surface faces the uterus and uterine vessels in the broad ligament, and the peritoneal recess here is termed the ovarian bursa. Above the superior extremity are the fimbria and distal section of the uterine tube. The inferior extremity points downwards towards the pelvic floor. The anterior border faces the posterior leaf of the broad ligament and contains the mesovarium. The posterior border is free and faces the peritoneum, which overlies the upper part of the internal iliac artery and vein, and the ureter. On the right side, superior and lateral to the ovary, are the ileocaecal junction, caecum and appendix. On the left side, the sigmoid colon passes over the superior pole of the ovary and joins the rectum, which lies between the medial surfaces of both ovaries. The mesosalpinx lies below the uterine tube. The ovarian ligament is inferior and medial. The mesovarium and ovary lie inferiorly at its fimbrial end. The round ligament is anterior to the tube. The superior and posterior surfaces of the tube lie free in the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 77.18).

In embryonic and early fetal life the ovaries are situated in the lumbar region near the kidneys. They gradually descend along the gubernaculum, stopping at the lesser pelvis. Accessory ovarian tissue may occur in the mesovarium or along the course of the gubernacula; rarely the ovaries may descend along the whole course of the gubernacula and are found in the labia majora. During pregnancy, the ovaries are lifted high in the pelvis and, by 14 weeks of gestation, become partly abdominal structures. By the third trimester they are totally abdominal structures and lie vertically behind and lateral to the parous uterus (see Ch. 78).

Peritoneal and ligamentous supports of the ovary

Vascular supply and lymphatic drainage

Arteries

The ovarian arteries are branches of the abdominal aorta and originate below the renal arteries. Each descends behind the peritoneum, and at the brim of the pelvis crosses the external iliac artery and vein to enter the true pelvic cavity. Here the artery turns medially in the ovarian suspensory ligament and splits into a branch to the mesovarium that supplies the ovary, and a branch that continues into the uterine broad ligament, below the uterine tube, and supplies the tube. There are variations in the site of the division to the ovary and tube (Fig. 77.21). On each side, a branch passes lateral to the uterus to unite with the uterine artery. Other branches accompany the round ligaments through the inguinal canal to the skin of the labium majus and the inguinal region. Early in intrauterine life the ovaries flank the vertebral column inferior to the kidneys, and so the ovarian arteries are relatively short, they gradually lengthen as the ovaries descend into the pelvis.

Veins

The ovarian veins emerge from the ovary as a plexus (pampiniform plexus) in the mesovarium and suspensory ligament (Fig. 77.3). Two veins emerge from the plexus and ascend with the ovarian artery: they usually merge into a single vessel before entering either the inferior vena cava on the right side, or the renal vein on the left side.

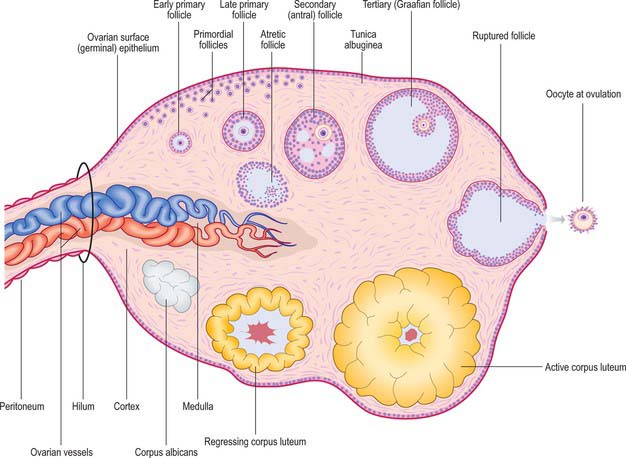

Microstructure

Ovarian cortex

Ovarian follicles

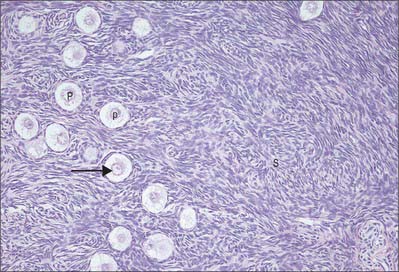

Primordial follicles

The development of ovarian follicles can be divided into different stages (Fig. 77.31). At birth, the ovarian cortex contains a superficial zone of primordial follicles. These consist of primary oocytes 25 μm in diameter, each surrounded by a single layer of flat follicular cells. The oocyte nuclei are slightly eccentric and have a characteristically prominent nucleolus. They contain the diploid number of chromosomes (duplicated as sister chromatids), arrested at the diplotene stage of meiotic prophase since before birth (Fig. 77.32). Many follicles degenerate either during prepubertal (including prenatal) life, or through atresia at some stage after beginning the process of cyclical maturation during the child-bearing period. Their remnants are visible as atretic follicles, the remains of which accumulate throughout the period of reproductive life. After puberty, cohorts of up to 20 primordial follicles become activated in each menstrual cycle (fewer are activated with advancing age). Their development takes a number of cycles. Of the follicles activated in each cohort, usually only one follicle from one or other ovary becomes dominant, reaches maturity and releases its oocyte at ovulation.

Primary follicles

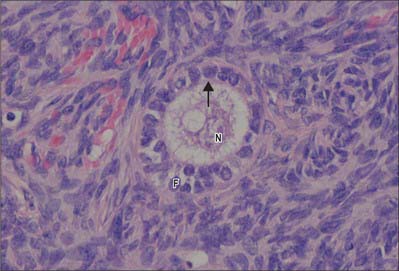

Primary follicles develop from primordial follicles. The first sign is a change in the follicle cells from flattened to cuboidal. This is followed by their proliferation to give rise to a multilayered follicle consisting of granulosa cells surrounded by a thick basal lamina (Fig. 77.33). Stromal cells immediately surrounding the follicle begin to differentiate into spindle-shaped cells, which constitute the theca folliculi which will become the theca interna. They are later surrounded by a more fibrous layer called the theca externa. At the same time the oocyte increases in size and secretes a thick layer of extracellular proteoglycan-rich material, the zona pellucida, between its plasma membrane and the surrounding granulosa cells of the early follicle. This is important for the process of fertilization. The granulosa cells in contact with the zona pellucida send cytoplasmic processes radially inwards and these contact oocyte microvilli at gap junctions, indicating communication between them (see Motta et al 2003). The follicular cells, in particular the granulosa cells, which are in functional contact with each other through gap junctions, continue to proliferate and so the thickness of the late primary follicle wall increases.

Secondary (antral) follicles

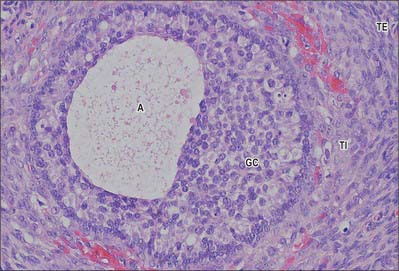

Secondary (antral) follicles develop from primary follicles. The number of granulosa cells continues to increase. Cavities begin to form between them filled with a clear fluid (liquor folliculi) containing hyaluronate, growth factors, and steroid hormones secreted by the granulosa cells. The follicle is now about 200 μm in diameter and usually lies deep in the cortex. These cavities coalesce to form one large fluid-filled space, the antrum. This is surrounded by a thin, uniform layer of granulosa cells, except at one pole of the follicle where a thickened granulosa layer envelops the eccentrically placed oocyte, to form the cumulus oophorus. The oocyte has now reached its maximum size of about 80 μm and the inner and outer thecae are clearly differentiated (Fig. 77.34). As follicles mature, the theca interna becomes more prominent and its cells more rounded and typical of steroid-secreting endocrine cells. These cells produce androstenedione from which the granulosa cells synthesize oestrogens (primarily oestradiol). Follicular development is stimulated by follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH).

Tertiary (Graafian) follicle

Although a number of follicles may progress to the secondary stage by about the first week of a menstrual cycle, usually only one tertiary follicle develops. The remainder become atretic. The surviving follicle increases considerably in size as the antrum takes up fluid from the surrounding tissues and expands to a diameter of 2 cm. The term Graafian follicle is often used to describe this mature follicular stage (Fig. 77.34). The oocyte and a surrounding ring of tightly adherent cells, the corona radiata, breaks away from the follicle wall and floats freely in the follicular fluid. The primary oocyte, which has remained in the first meiotic prophase since fetal life, completes its first meiotic division to produce the almost equally large secondary oocyte and a small first polar body with very little cytoplasm. The secondary haploid oocyte immediately begins its second meiotic division, but when it reaches metaphase, the process is arrested until fertilization has occurred. The follicle moves to the superficial cortex, causing the surface of the ovary to bulge. The tissues at the point of contact (the stigma) with the tough tunica albuginea and ovarian surface epithelium are eroded until the follicle ruptures and its contents are released into the peritoneal cavity for capture by the fimbria of the uterine tube. The oocyte at ovulation is still surrounded by its zona pellucida and corona radiata of granulosa cells. If fertilization does not occur, it begins to degenerate after 24 to 48 hours.

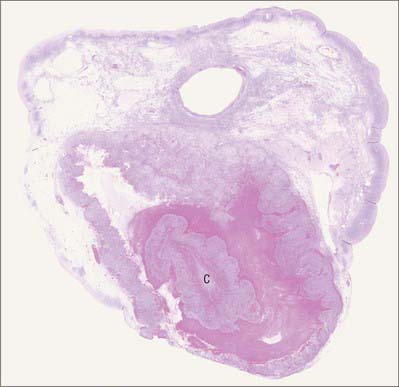

Corpus luteum

After ovulation, the remainder of the follicle becomes the corpus luteum (Fig. 77.35). The walls of the empty follicle collapse and fold. The granulosa cells increase in size and synthesize a cytoplasmic carotenoid pigment (lutein) giving them a yellowish colour (hence corpus luteum). These large (30–50 μm) granulosa lutein cells form most of the corpus luteum. The basal lamina surrounding the follicle breaks down, and numerous smaller theca lutein cells infiltrate the folds of the cellular mass, accompanied by capillaries and connective tissue. Extravasated blood from thecal capillaries accumulates in the centre as a small clot, but this rapidly resolves and is replaced by connective tissue. All lutein cells have a cytoplasm filled with abundant smooth endoplasmic reticulum, characteristic of steroid synthesizing endocrine cells. Granulosa lutein cells secrete progesterone and oestradiol (from aromatization of androstenedione, which is synthesized by theca lutein cells). The two cell types also respond differently to circulating gonadotropins. Theca lutein cells express receptors for human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG). If the oocyte is not fertilized, the corpus luteum (of menstruation) functions for 12 to 14 days after ovulation, then atrophies. The lutein cells undergo fatty degeneration, autolysis, removal by macrophages and gradual replacement with fibrous tissue. Eventually, after 2 months, a small, whitish scar-like corpus albicans is all that remains.

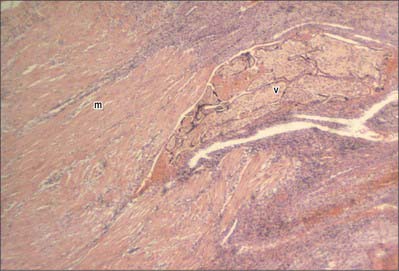

Ovarian medulla

The medulla is highly vascular. It contains numerous veins and spiral arteries, which enter the hilum from the mesovarium and lie within a loose connective tissue stroma. Small numbers of cells (hilus cells) with characteristics similar to interstitial (Leydig) cells in the testis are found in the medulla at the hilum, and they may be a source of androgens.

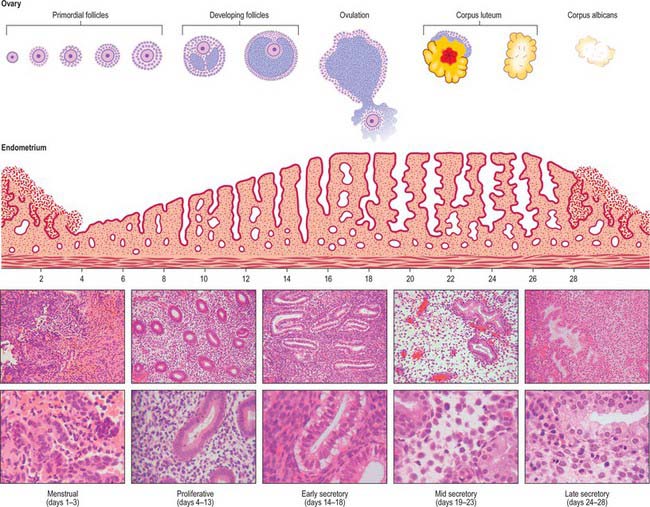

MENSTRUAL CYCLE

The changes that occur in the endometrium during the menstrual cycle may be divided into three phases: proliferative, secretory and menstrual (Fig. 77.36).

SECRETORY PHASE

The secretory phase coincides with the luteal phase of the ovarian cycle. The endometrial changes are driven by progesterone and oestrogen secreted by the corpus luteum. Steroid receptors in the endometrium activate a programme of new gene expression that produces, in the following 7 days, a highly regulated sequence of differentiative events, presumably required to prepare the tissue for blastocyst implantation. Part of the response is direct, but there is evidence that some of the effects may be mediated through growth factors. The first morphological effects of progesterone are evident 24 to 36 hours after ovulation (which occurs 14 days before the next menstrual flow). In the early secretory phase, glycogen masses accumulate in the basal cytoplasm of the epithelial cells lining the glands, where they are often associated with lipid. Giant mitochondria appear and are associated with semi-rough endoplasmic reticulum. There is an obvious increased polarization of the gland cells: nuclei are displaced towards the centre of the cells and Golgi apparatus and secretory vesicles accumulate in the supranuclear cytoplasm. The nuclear channel system is prominent and nuclei enlarge. Nascent secretory products may be detected immunohistochemically within the cells. Progestational effects on the stroma (known as the decidual reaction) are also evident in the early secretory phase. Nuclear enlargement occurs and the packing density of the resident stromal cells increases, due in part to the increase in volume of gland lumina and onset of secretory activity in the epithelial compartment.

Ultrasound is frequently used in the clinical evaluation of the endometrium. In the early secretory phase the endometrium is identified as a thin echogenic line, a consequence of specular reflection from the interface between opposing surfaces of endometrium. During the late proliferative phase the endometrium appears as a triple layer: a central echogenic line (due to the opposed endometrial surfaces), surrounded by a thicker hypoechoic functional layer, and bounded by an outer echogenic basal layer. During the secretory phase the functional layer surrounding the echogenic line becomes more hyperechoic as a result of the increased mucus and glycogen within the glands and the increased number of interfaces caused by the development of tortuous spiral arteries (Fig. 77.37).

PREGNANCY AND PARTURITION

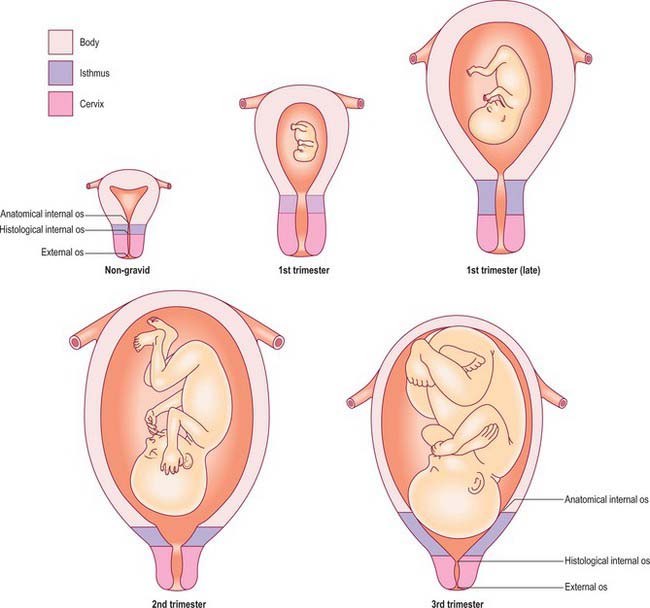

THE UTERUS IN PREGNANCY

The function of the uterus in pregnancy is to retain the developing fetus and to provide a protected environment until a stage at which the fetus is capable of surviving ex utero. The uterus must grow, facilitate delivery of the fetus and then involute. At the same time smooth muscle cells must be stretched by the growing fetus without producing miscarriage or premature labour.

The upper third of the cervix (isthmus) is gradually taken up into the uterine body during the second month to form the ‘lower segment’ (Fig. 77.38). The isthmus hypertrophies like the uterine body during the first trimester and triples in length to about 3 cm. From the second trimester the wall of the isthmus and that of the body are the same thickness and their junction is no longer visible externally. This condition persists until the middle of the third trimester when the junction between the body and the isthmus can sometimes be recognized as a transverse linear depression; the musculature above the depression is thicker than that below. The depression forms just below the vesico-uterine pouch and is thought to correspond to the level of the anatomical internal os (upper margin of lower segment). It is the anatomical landmark used at the time of a lower segment caesarean section to ensure that the uterine incision is not in the body of the uterus. The lower segment is less vascular than the upper part of the uterus. Moreover, the risk of rupture of a lower segment uterine scar in subsequent pregnancies is significantly reduced compared to rupture of a scar in the body of the uterus (classical caesarean section).

Growth of the uterus in pregnancy

Anatomical surface landmarks can be used to estimate uterine size and therefore gestational age. The uterus is usually palpable just above the pubic symphysis by the 12th week; if is retroverted it may not be palpable in the abdomen until a little later. By the 20th week of pregnancy the uterine fundus is at the level of the umbilicus, and by 36 weeks the fundus has reached the xiphisternum. In practice the gestational age is now calculated by ultrasound measurement of the fetal crown–rump length in the first trimester (Fig. 77.39). For women presenting after the first trimester, dating is less accurate and is based on measurement of the head circumference. Subsequent assessment of fetal size up to 24 weeks relies on abdominal palpation and correlating gestational age with anatomical landmarks. From 24 weeks of gestation serial measurement of the distance between the pubic symphysis and the uterine fundus is used. The symphysis–fundal height (SFH) measurement acts primarily as a screening method, and if there is a concern that the SFH is either above or below the normal range a more accurate assessment of fetal size and amniotic fluid volume is made using ultrasound. Dating of pregnancy based on fetal biometry rather than menstrual history has significantly reduced the number of pregnancies requiring induction of labour for post-term.

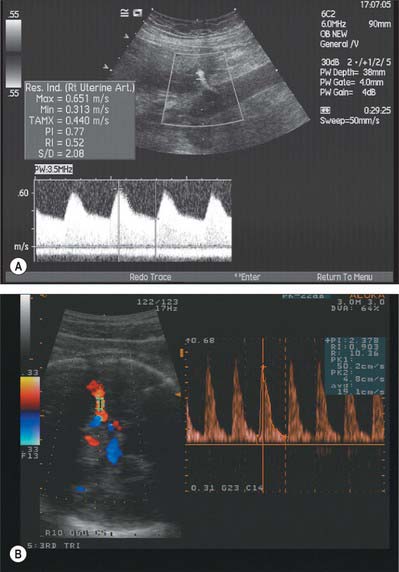

Doppler can be used to assess the placental and fetal circulations. Doppler assessment of the uterine arteries can play an important role in screening for impaired placentation and its complications of pre-eclampsia, intrauterine growth restriction and perinatal death, and assessment of the fetal circulation (e.g. umbilical artery, middle cerebral artery) can aid clinical management, such as timing of delivery in a growth restricted baby (Fig. 77.40A,B).

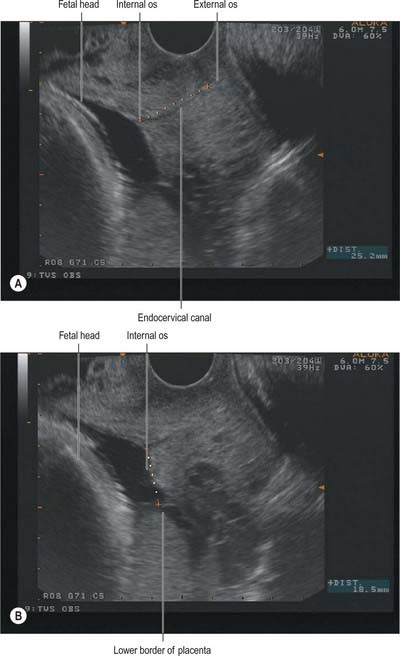

Cervix and pregnancy

The cervix can be viewed during pregnancy by transvaginal ultrasound examination. The cervical length, dilatation of the internal os and bulging of the membranes into the canal can be assessed (Fig. 77.41A,B). Measurement of cervical length on ultrasound appears to be a strong predictor of preterm labour: the shorter the cervix, the greater the risk of premature delivery. In clinical practice cervical length has been used to screen women at high risk of preterm labour or to screen symptomatic women in threatened preterm labour in order to plan appropriate management.

PELVIC CHANGES IN PREGNANCY

The presence of a pregnant uterus results in a change in the centre of gravity of the body, especially in late pregnancy (Fig. 77.42). In order to compensate for this, the mother tends to straighten her cervical and thoracic spine, and throw her shoulders back, resulting in a compensatory lumbar lordosis. There is also a softening of the pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joints, caused by production of relaxin and other pregnancy hormones. This increased mobility produces a form of pelvic instability, so that the pregnant woman tends to walk with a waddling gait. Softening also produces an increase in pelvic diameter, which is of benefit during the time of labour. Significant joint relaxation can be associated with pain, called symphysis pubis diastasis: in severe cases radiographs show that when a woman stands on one leg the two halves of the symphysis are at different levels.

PLACENTAL LOCATION

In about 1% of pregnancies the position of the placenta will remain over, or in close proximity to, the internal cervical os at the end of pregnancy (Figs 77.41B, 77.43). This condition is called placenta praevia and is associated with vaginal bleeding during pregnancy and labour. If the placenta covers the internal os, or the lower edge is less than 2 cm from the internal os, delivery by caesarean section is likely to be needed. Women with placenta praevia are at an increased risk of having a morbidly adherent placenta if they have an anterior placenta praevia and have had previous uterine surgery, e.g. caesarean section. Pathological forms of adherence or penetration include placenta accreta, where the placenta displays exceptional adherence to the decidua basalis; placenta increta, where the myometrium is invaded; and placenta percreta, when the invasion by placental tissue passes completely through the uterine wall (Fig. 77.44).

LABOUR

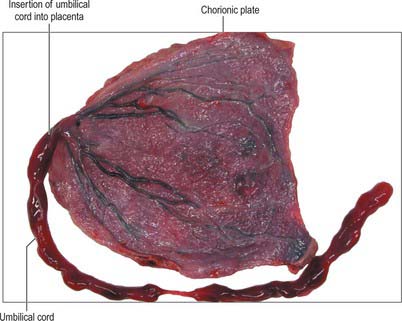

The placenta after delivery

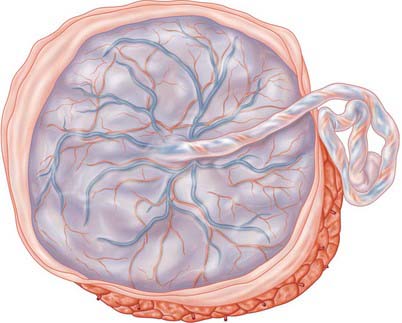

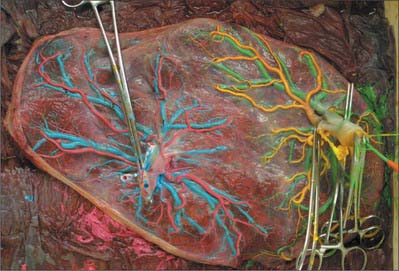

Separation of the placenta from the uterine wall takes place along the plane of the stratum spongiosum. It extends beyond the placental area, detaching the villous placenta, with associated fibrinoid matrix and small amounts of decidua basale, the chorio-amnion, together with a superficial layer of the fused decidua capsularis, and the decidua parietalis. When the placenta and membranes have been expelled, a thin layer of stratum spongiosum is left as a lining for the uterus: it soon degenerates and is cast off in the early part of the puerperium. A new epithelial lining for the uterus is regenerated from the remaining stratum basale. The expelled placenta is a flattened discoid mass with an approximately circular or oval outline (Fig. 77.45). It has an average volume of 500 ml (range 200–950 ml), a weight of 470 g (range 200–800 g), a diameter of 185 mm (range 150–200 mm), a thickness of 23 mm (range 10–40 mm), and a surface area of approximately 30,000 mm2. It is thickest at its centre (the original embryonic pole), and rapidly thins towards its periphery where it continues as the chorion laeve.

Macroscopically, the fetal or inner surface, covered by amnion, is smooth, shiny and transparent, so that the mottled appearance of the subjacent chorion, to which it is closely applied, can be seen. The umbilical cord is usually attached near the centre of the fetal surface, and branches of the umbilical vessels radiate out under the amnion from this point; the veins are deeper and larger than the arteries. The maternal surface of the placenta is finely granular and mapped into some 15–30 lobes by a series of fissures or grooves. The placental lobes, which are often somewhat loosely termed cotyledons, correspond in large measure to the major branches of the umbilical vessels. The grooves correspond to the bases of incomplete placental septa, which become increasingly prominent from the third month onwards. They extend from the maternal aspect of the intervillous space (the basal plate) towards, but do not quite reach, the chorionic plate. The septa are complex structures composed of components of the cytotrophoblastic shell and residual syncytium, together with maternally derived material including decidual cells, occasional blood vessels and gland remnants, collagenous and fibrinoid extracellular matrix and, in the later months of pregnancy, foci of degeneration.

In multiple pregnancies the number of placentas is determined by the zygosity. Dizygotic pregnancies will always have two placentas (dichorionic); monozygotic pregnancies usually have a single placenta (monochorionic) but 33% will have two placentas. The number of placentas in monozygotic pregnancies is determined by the timing of splitting of the embryonic mass. If the single embryonic mass splits into two within 3 days of fertilization, each fetus will have its own placenta and amniotic sac (dichorionic diamniotic); splitting after the 3rd day following fertilization results in a monochorionic diamniotic (two amniotic sacs) pregnancy and vascular communication within the two placental circulations (Fig. 77.46); splitting after the 9th day results in a single placenta and single amniotic sac (monochorionic monoamniotic); and splitting after the 12th day results in conjoined twins.

Placental variations

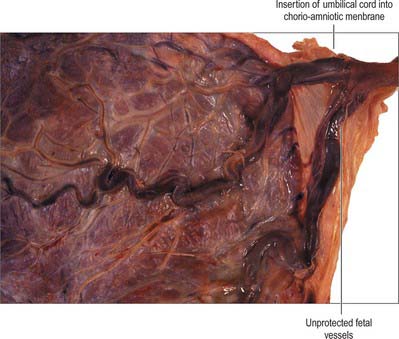

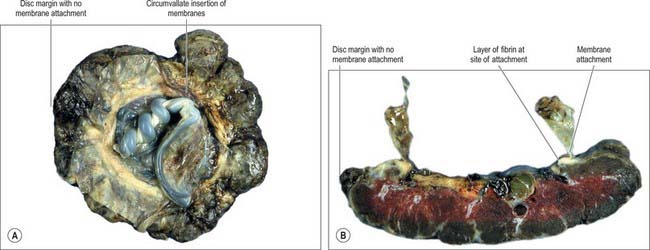

The umbilical cord is usually attached near the centre of the placenta. It may insert at any point between its centre and margin, a condition known as a battledore placenta (Fig. 77.47). Occasionally the cord fails to reach the placenta itself and ends in the membranes as a velamentous insertion. When insertion of the cord is velamentous, the larger branches of the umbilical vessels traverse the membranes before they reach and ramify on the placenta (Fig. 77.48). They travel unprotected through the membranes to the placenta, which puts the fetus at risk because compression or tearing of the vessels can disrupt blood flow to and from the fetus. This can be particularly problematic when the vessels present themselves across the cervical os, a condition called vaso previa. A small accessory (succenturiate) placental lobe is occasionally present, connected to the main organ by membranes and blood vessels. It may be retained in utero after delivery of the main placental mass and cause postpartum haemorrhage. Other variations include placenta membranacea, in which villous stems and their branches persist over the whole chorion; and placenta circumvallate, where the placental margin is undercut by a deep groove (Fig. 77.49A,B).

Fig. 77.47 A battledore placenta showing marginal insertion of the umbilical cord into the placenta.

(By courtesy of Dr Michael Ashworth, Consultant Histopathologist, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children, London.)