Chapter 3 Female Reproductive Anatomy and Embryology

The scope of obstetrics and gynecology assumes a reasonable background in reproductive anatomy, embryology, physiology (see Chapter 4), and endocrinology (see Chapter 5 and Part 4). A physician cannot effectively practice obstetrics and gynecology without understanding the physiologic processes that transpire in a woman’s life as she passes through infancy, adolescence, reproductive maturity, and the climacteric. As the various clinical problems are addressed, it is important to consider those anatomic, developmental, and physiologic changes that normally take place at key points in a woman’s life cycle.

Development of the External Genitalia

Development of the External Genitalia

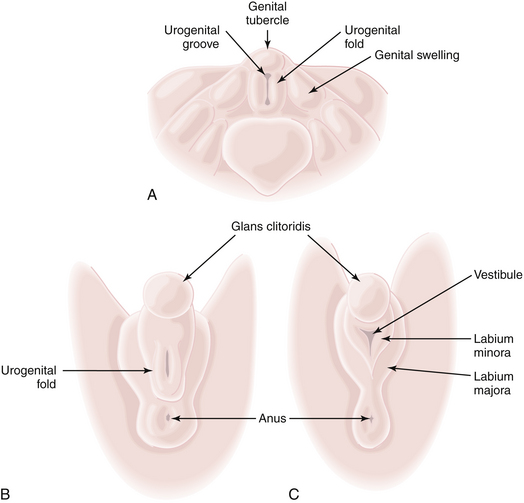

The external genitalia of the fetus are readily distinguishable as female at about 12 weeks (Figure 3-1). In the male, the urethral ostium is located conspicuously on the elongated phallus by this time and is smaller, owing to urogenital fold fusion dorsally, which produces a prominent raphe from the anus to the urethral ostium. In the female, the hymen is usually perforated by the time delivery occurs.

Anatomy of the External Genitalia

Anatomy of the External Genitalia

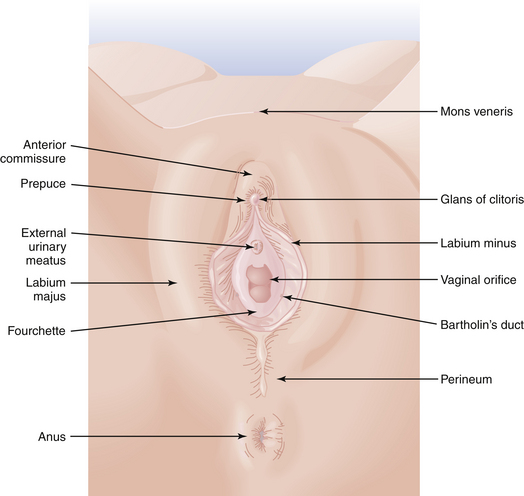

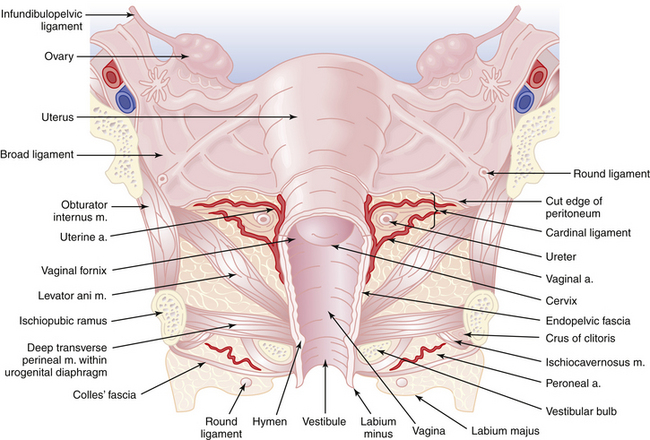

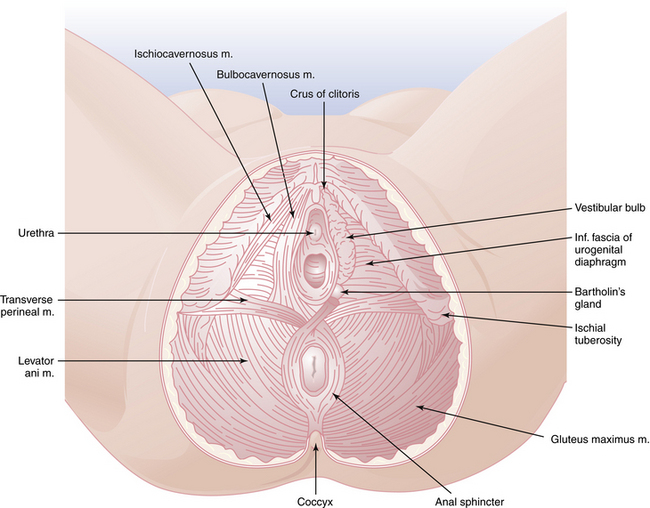

The perineum represents the inferior boundary of the pelvis. It is bounded superiorly by the levator ani muscles and inferiorly by the skin between the thighs (Figure 3-2). Anteriorly, the perineum extends to the symphysis pubis and the inferior borders of the pubic bones. Posteriorly, it is limited by the ischial tuberosities, the sacrotuberous ligaments, and the coccyx. The superficial and deep transverse perineal muscles cross the pelvic outlet between the two ischial tuberosities and come together at the perineal body. They divide the space into the urogenital triangle anteriorly and the anal triangle posteriorly.

FIGURE 3-2 The perineum, showing superficial structures on the left and deeper structures on the right.

VULVA

The external genitalia are referred to collectively as the vulva. As shown in Figure 3-3, the vulva includes the mons veneris, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vulvovaginal (Bartholin’s) glands, fourchette, and perineum. The most prominent features of the vulva, the labia majora, are large, hair-covered folds of skin that contain sebaceous glands and subcutaneous fat and lie on either side of the introitus. The labia minora lie medially and contain no hair but have a rich supply of venous sinuses, sebaceous glands, and nerves. The labia minora may vary from scarcely noticeable structures to leaf-like flaps measuring up to 3 cm in length. Anteriorly, each splits into two folds. The posterior two folds attach to the inferior surface of the clitoris, at which point they unite to form the frenulum of the clitoris. The anterior folds are united in a hood-like configuration over the clitoris, forming the prepuce. Posteriorly, the labia minora may extend almost to the fourchette.

Internal Genital Development

Internal Genital Development

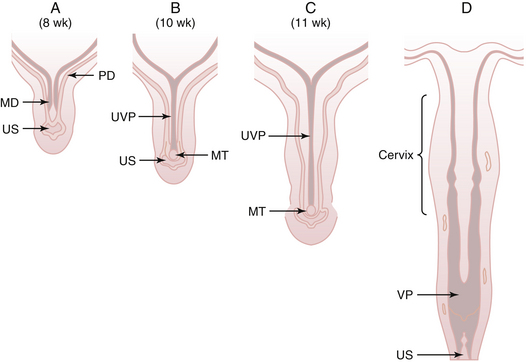

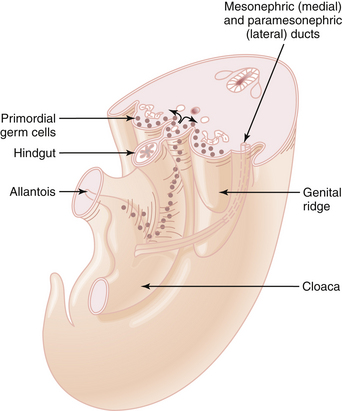

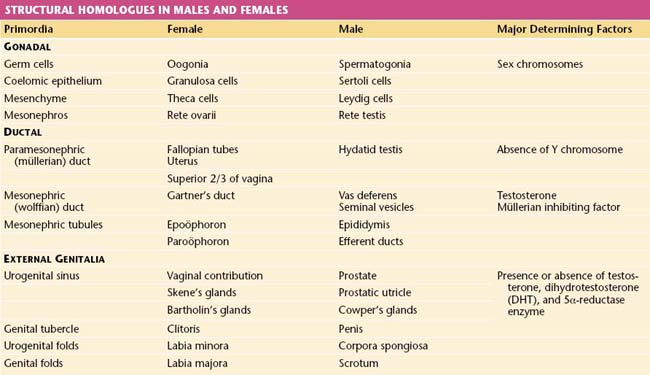

Mesonephric duct development occurs in each urogenital ridge between weeks 2 and 4 and is thought to influence the growth and development of the paramesonephric ducts. The mesonephric ducts terminate caudally by opening into the urogenital sinus. First evidence of each paramesonephric duct is seen at 6 weeks’ gestation as a groove in the coelomic epithelium of the paired urogenital ridges, lateral to the cranial pole of the mesonephric duct. Each paramesonephric duct opens into the coelomic cavity cranially at a point destined to become a tubal ostium. Coursing caudally at first, parallel to the developing mesonephric duct, the blind distal end of each paramesonephric duct eventually crosses dorsal to the mesonephric duct, and the two ducts approximate in the midline. The two paramesonephric ducts fuse terminally at the urogenital septum, forming the uterovaginal primordium. The distal point of fusion is known as the müllerian tubercle (Müller’s tubercle) and can be seen protruding into the urogenital sinus dorsally in embryos at 9 to 10 weeks’ gestation (Figure 3-4). Later dissolution of the septum between the fused paramesonephric ducts leads to the development of a single uterine fundus, cervix, and, according to some investigators, the upper vagina.

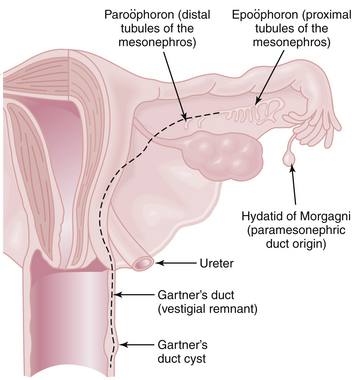

Degeneration of the mesonephric ducts is progressive from 10 to 16 weeks in the female fetus, although vestigial remnants of the latter may be noted in the adult (Gartner’s duct cyst, paroöphoron, epoöphoron) (Figure 3-5). The myometrium and endometrial stroma are derived from adjacent mesenchyme; the glandular epithelium of the fallopian tubes, uterus, and cervix is derived from the paramesonephric duct.

VAGINA

The vagina is a flattened tube extending posterosuperiorly from the hymenal ring at the introitus up to the fornices that surround the cervix (Figure 3-6). Its epithelium, which is stratified squamous in type, is normally devoid of mucous glands and hair follicles and is nonkeratinized. Gestational exposure to diethylstilbestrol (taken by the mother) may result in columnar glands interspersed with the squamous epithelium of the upper two thirds of the vagina (vaginal adenosis). Deep to the vaginal epithelium are the muscular coats of the vagina, which consist of an inner circular and an outer longitudinal smooth muscle layer. Remnants of the mesonephric ducts may sometimes be demonstrated along the vaginal wall in the subepithelial layers and may give rise to Gartner’s duct cysts. The adult vagina averages about 8 cm in length, although its size varies considerably with age, parity, and the status of ovarian function. An important anatomic feature is the immediate proximity of the posterior fornix of the vagina to the pouch of Douglas, which allows easy access to the peritoneal cavity from the vagina, by either culdocentesis or colpotomy.

UTERUS

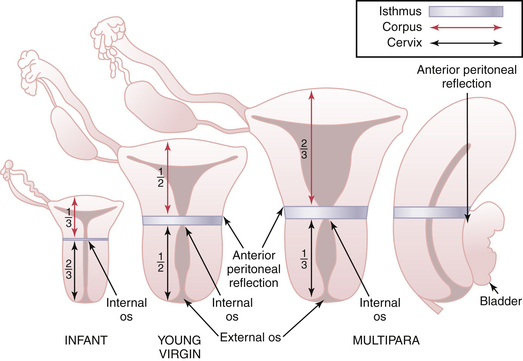

The cervix is generally 2 to 3 cm in length. In infants and children, the cervix is proportionately longer than the uterine corpus (Figure 3-7). The portion that protrudes into the vagina and is surrounded by the fornices is covered with a nonkeratinizing squamous epithelium. At about the external cervical os, the squamous epithelium covering the ectocervix changes to simple columnar epithelium, the site of transition being referred to as the squamocolumnar junction. The cervical canal is lined by irregular, arborized, simple columnar epithelium, which extends into the stroma as cervical “glands” or crypts.

FIGURE 3-7 Changing proportion of the uterine cervix and corpus from infancy to adulthood.

(Modified from Cunningham FG, MacDonald PC, Gant NF, et al [eds]: Williams Obstetrics, 20th ed. East Norwalk, Conn, Appleton & Lange, 1997.)

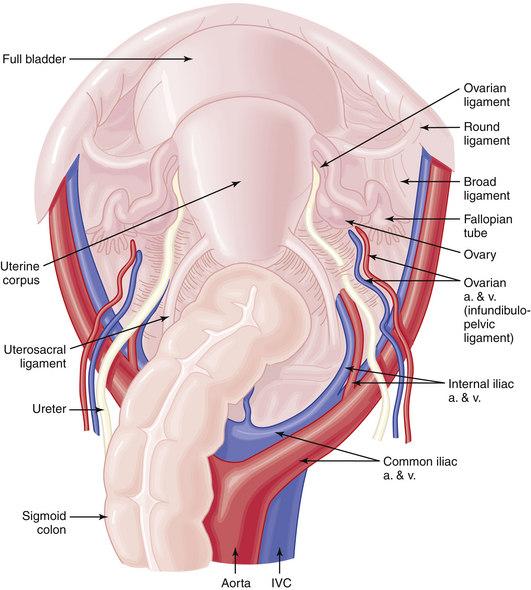

Four paired sets of ligaments are attached to the uterus (Figure 3-8). Each round ligament inserts on the anterior surface of the uterus just in front of the fallopian tube, passes to the pelvic side wall in a fold of the broad ligament, traverses the inguinal canal, and ends in the labium majus. The round ligaments are of little supportive value in preventing uterine prolapse but help to keep the uterus anteverted. The uterosacral ligaments are condensations of the endopelvic fascia that arise from the sacral fascia and insert into the posteroinferior portion of the uterus at about the level of the isthmus. These ligaments contain sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve fibers that supply the uterus. They provide important support for the uterus and are also significant in precluding the development of an enterocele. The cardinal ligaments (Mackenrodt’s) are the other important supporting structures of the uterus that prevent prolapse. They extend from the pelvic fascia on the lateral pelvic walls and insert into the lateral portion of the cervix and vagina, reaching superiorly to the level of the isthmus. The pubocervical ligaments pass anteriorly around the bladder to the posterior surface of the pubic symphysis.

Normal Embryologic Development of the Ovary

Normal Embryologic Development of the Ovary

As early as 3 weeks’ gestation, relatively large primordial germ cells appear intermixed with other cells in the endoderm of the yolk sac wall of the primitive hindgut. These germ cell precursors migrate along the hindgut dorsal mesentery (Figure 3-9) and are all contained in the mesenchyme of the undifferentiated urogenital ridge by 8 weeks’ gestation. Subsequent replication of these cells by mitotic division occurs, with maximal mitotic activity noted up to 20 weeks and cessation noted by term. These oogonia, the end result of this germ cell proliferation, are incorporated into the cortical sex cords of the genital ridge.

Histologically, the first evidence of follicles is seen at about 20 weeks, with germ cells surrounded by flattened cells derived from the cortical sex cords. These flattened cells are recognizable as granulosa cells of coelomic epithelial origin and theca cells of mesenchymal origin. The oogonia enter the prophase of the first meiotic division and are then called primary oocytes (see Chapter 4). It has been estimated that more than 2 million primary oocytes, or their precursors, are present at 20 weeks’ gestation, but only about 300,000 to 500,000 primordial follicles are present by 7 years of age.

Regression of the primary sex cords in the medulla produces the rete ovarii, which are found histologically in the hilus of the ovary along with another testicular analogue called Leydig’s cells, which are thought to be derived from mesenchyme. Vestiges of the rete ovarii and of the degenerating mesonephros may also be noted at times in the mesovarium or mesosalpinx. Structural homologues in males and females are shown in Table 3-1.

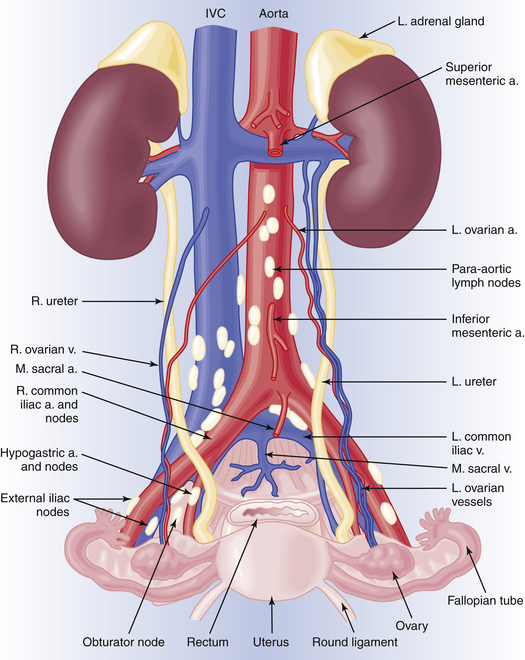

ANATOMY OF THE OVARIES

The blood supply to the ovaries is provided by the long ovarian arteries, which arise from the abdominal aorta immediately below the renal arteries. These vessels course downward and cross laterally over the ureter at the level of the pelvic brim, passing branches to the ureter and the fallopian tube. The ovary also receives substantial blood supply from the uterine artery through the uterine-ovarian arterial anastomosis. The venous drainage from the right ovary is directly into the inferior vena cava, whereas that from the left ovary is into the left renal vein (Figure 3-10).

LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE

The lymphatic drainage of the vulva and lower vagina is principally to the inguinofemoral lymph nodes and then to the external iliac chains (see Figure 3-10). The lymphatic drainage of the cervix takes place through the parametria (cardinal ligaments) to the pelvic nodes (the hypogastric, obturator, and external iliac groups) and then to the common iliac and para-aortic chains. The lymphatic drainage from the endometrium is through the broad ligament and infundibulopelvic ligament to the pelvic and para-aortic chains. The lymphatics of the ovaries pass via the infundibulopelvic ligaments to the pelvic and para-aortic nodes (see Figure 3-10).

ANATOMY OF THE LOWER ABDOMINAL WALL

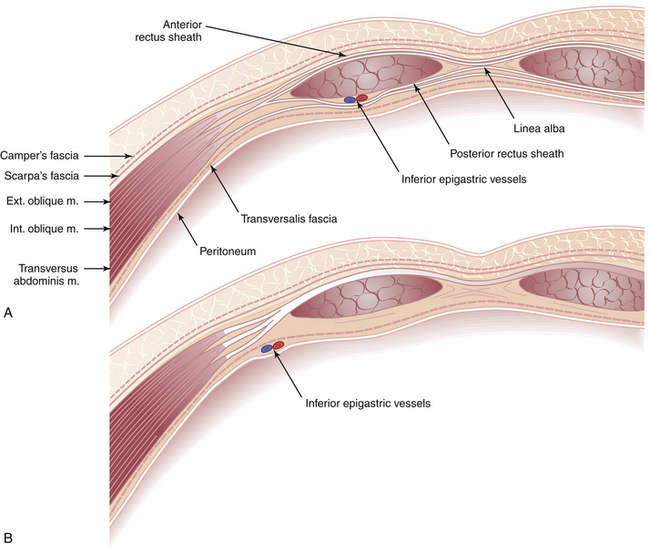

Because most intraabdominal gynecologic operations are performed through lower abdominal incisions, it is important to review the anatomy of the lower abdominal wall with special reference to the muscles and fasciae. After transecting the skin, subcutaneous fat, superficial fascia (Camper’s), and deep fascia (Scarpa’s), the anterior rectus sheath is encountered (Figure 3-11). The rectus sheath is a strong fibrous compartment formed by the aponeuroses of the three lateral abdominal wall muscles. The aponeuroses meet in the midline to form the linea alba and partially encase the two rectus abdominis muscles. The composition of the rectus sheath differs in its upper and lower portions. Above the midpoint between the umbilicus and the symphysis pubis, the rectus muscle is encased anteriorly by the aponeurosis of the external oblique and the anterior lamina of the internal oblique aponeurosis and posteriorly by the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis and the posterior lamina of the internal oblique aponeurosis. In the lower fourth of the abdomen, the posterior aponeurotic layer of the sheath terminates in a free crescentic margin, the semilunar fold of Douglas.

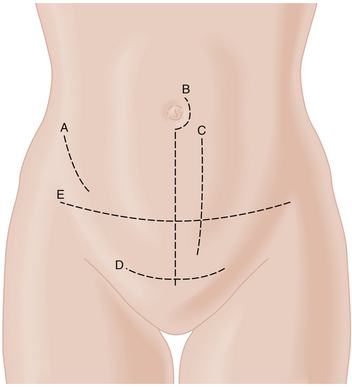

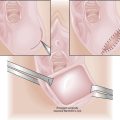

ABDOMINAL WALL INCISIONS

The most commonly used lower abdominal incision in gynecologic surgery is the Pfannenstiel incision (Figure 3-12). Although it does not always give sufficient exposure for extensive operations, it has cosmetic advantages in that it is generally only 2 cm above the symphysis pubis, and the scar is later covered by the pubic hair. Because the rectus abdominis muscles are not cut, eviscerations and wound hernias are extremely uncommon. For extensive pelvic procedures (e.g., radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy), a transverse muscle–cutting incision (Bardenheuer or Maylard) at a slightly higher level in the lower abdomen gives sufficient exposure. In addition, the skin incision falls within the lines of Langer, so a good cosmetic result can be expected. When it is anticipated that upper abdominal exploration will be necessary, such as in a patient with suspected ovarian cancer, a midline incision through the linea alba or a paramedian vertical incision is indicated.

Agur A.M.R., editor. Grant’s Atlas of Anatomy, 9th ed., Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1991.

Clemente C.D. Anatomy: An Atlas of the Human Body, 4th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1997.

Cunningham E.G., MacDonald P.C., Gant N.F., et al, editors. Williams Obstetrics, 20th ed., Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange, 1997.