Chapter 16

Female Genitalia1

In young girls, as I said, and in women past childbearing, it [the uterus] is without blood, and about the size of a bean. In a marriageable virgin it has the magnitude and form of a pear. In women who have borne children, and are still fruitful, it equals in bulk a small gourd or a goose’s egg; at the same time, together with the breasts, it swells and softens, becomes more fleshy, and is heat increased.

William Harvey (1578–1657)

General Considerations

Records of obstetrics and gynecology date back to the time of Hippocrates in 400 BCE. He was probably the first physician to describe midwifery, menstruation, sterility, symptoms of pregnancy, and puerperal (the period after labor) infections. Most of the early gynecologic history stems from Soranus in the second century CE. His works included chapters on anatomy, menstruation, fertility, signs of pregnancy, labor, care of the infant, dysmenorrhea (painful menstruation), uterine hemorrhage, and even the use of vaginal specula.

William Harvey, who devised the theory of blood circulation, was also responsible for a monumental treatise on obstetrics. This work, published in 1651, included a detailed assessment of uterine changes throughout life.

The eighteenth century was a period of a further understanding of pregnancy, labor, and fertility. However, it was not until the nineteenth century that diseases of the female genitalia were better understood. As recently as 1872, Emil Noeggerath published his investigations on gonorrhea, which ultimately changed the opinion of the medical world about the significance of this disorder. He was the first to suggest that “latent gonorrhea” was associated with sterility in women. Although the first cesarean section was described in 1596 by Scipione Mercurio, the development of the current technique of Max Sänger was described as recently as 1882.

In 2011, cancer of the uterine corpus, also known as endometrial cancer, the most common cancer of the female reproductive organs, accounted for 6% of all cancers and 3% of all cancer deaths in women in the United States. It is the fourth most common cancer found in women, after breast cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer. Obesity and greater abdominal fatness increase the risk of endometrial cancer, most likely by increasing the amount of estrogen in the body. Increased estrogen exposure is a strong risk factor for endometrial cancer. Other factors that increase estrogen exposure include menopausal estrogen therapy (without use of progestin), late menopause, never having children, and a history of polycystic ovary syndrome. In 2011, there were 46,470 new cases and 8120 deaths from cancer of the uterus. The lifetime risk for development of cancer of the uterus is 1 per 38. For all cases of cancer of the uterus, the 5-year relative survival rate is 84%. Although the mortality rate has declined slightly since the 1980s among white women, it has remained stable among other racial and ethnic groups. Although the incidence rate of uterine cancer is lower for African-American women than for white women, the mortality rate among African-American women is nearly twice as high. The 1- and 5-year relative survival rates for uterine corpus cancer are 92% and 83%, respectively. The 5-year survival rate is 96%, 68%, or 17%, if the cancer is diagnosed at a local, regional, or distant stage, respectively. Relative survival in whites exceeds that for African Americans by more than 8% at every stage of diagnosis.

Between the mid-1950s and 1992, deaths from invasive cancer of the cervix in the United States dropped by 74%. The decline in mortality from cervical cancer is largely attributed to early detection by physical examination. It has been estimated that noninvasive cervical cancer (carcinoma in situ) is approximately four times more common than invasive cervical cancer. In the United States, the widespread use of the Papanicolaou (Pap)2 test has decreased the incidence and mortality rate by 40% since the mid-1970s. Most invasive cervical carcinomas are found in women who have not had regular Pap tests. In 2011, there were 12,710 new cases of invasive cervical cancer diagnosed, and 4290 women died from this disease. The death rate continues to decline by approximately 2% per year. An American woman has a 0.78% lifetime risk (1 per 128) for development of cervical cancer and a 0.27% risk of dying from the disease. The 5-year relative survival rate for the earliest stage of invasive cervical cancer is 92%, and the overall (all cases considered together) 5-year survival rate is 71%.

Of the many risk factors that have been evaluated, young age at first sexual intercourse, multiple sexual partners, infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV), infection with herpes simplex virus, infection with human immunodeficiency virus, immunosuppression, and a history of cervical dysplasia are most often associated with an increased risk of cervical cancer. The most important risk factor for cervical cancer is infection by the HPV. Because the course of dysplasia development takes several years from the time of initial HPV infection, the guidelines indicate that a woman should be screened after being sexually active for 3 years. HPVs are a group of more than 100 types of viruses, some of which can cause warts, or papillomas; these are noncancerous (benign) tumors. Certain other types of HPV can cause cancer of the cervix. These are called high-risk or carcinogenic types of HPV, and approximately 70% of all cervical cancers are caused by HPV types 16 and 18. In women older than 30, an HPV test may be conducted at the same time as a Pap test.

Vaccines have been developed that protect against infection with some types of HPV, which may reduce cervical cancer rates in the future. Two vaccines are approved for the prevention of the most common types of HPV infection that cause cervical cancer: quadrivalent HPV recombinant vaccine (Gardasil®) is recommended for use in females 9 to 26 years of age, and HPV bivalent vaccine (Cervarix®) in females 10 to 25 years of age. Gardasil protects against types 6, 11, 16 and 18; Cervarix protects against types 16 and 18. The Gardasil vaccine entails a series of three injections over a 6-month period. To be most effective, the vaccine should be given before a person becomes sexually active. In December 2010, Gardasil was also approved for use in males 9 to 26 years of age to prevent anal cancer and associated precancerous lesions; approximately 90% of anal cancers have been linked to HPV infection. These vaccines cannot protect against established infections, nor do they protect against all HPV types.

Although ovarian carcinoma accounts for only 3% of all cancers in women, it is the cause of 6% of all cancer deaths in women. It is the fifth leading cause of cancer death and the leading gynecologic malignancy in women in the United States. Cancer of the ovary accounts for nearly 50% of all deaths from gynecologic malignancies. The most important risk factor is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. In 2011, there were 21,990 new cases of ovarian cancer and 15,460 deaths from it. The lifetime risk for development of ovarian cancer is 1 per 59; the incidence is 1.4 per 100,000 women younger than 40 years, but it increases to 45 per 100,000 women older than 60 years. The incidence has been declining by 1% per year since 1992. The carefully performed pelvic examination has been shown to be the cornerstone of diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

Structure and Physiologic Characteristics

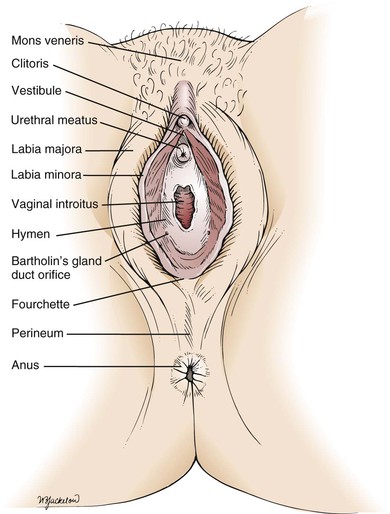

The external female genitalia are shown in Figure 16-1. The vulva consists of the mons veneris, the labia majora, the labia minora, the clitoris, the vestibule and its glands, the urethral meatus, and the vaginal introitus. The mons veneris is a rounded prominence of fat tissue overlying the pubic symphysis. The labia majora are two wide skinfolds that form the lateral boundaries of the vulva. They meet anteriorly at the mons veneris to form the anterior commissure. The labia majora and the mons veneris have hair follicles and sebaceous glands. The labia majora correspond to the scrotum in the man. The labia minora are two narrow, pigmented skinfolds that lie between the labia majora and enclose the vestibule, which is the area lying between the labia minora. Anteriorly, the two labia minora form the prepuce of the clitoris. The clitoris, analogous to the penis, consists of erectile tissue and a rich supply of nerve endings. It has a glans and two corpora cavernosa. The external urethral meatus is located in the anterior portion of the vestibule below the clitoris. Paraurethral glands, or Skene’s glands, are small glands that open lateral to the urethra. Secretion of sebaceous glands in this area protects the vulnerable tissues against urine.

Figure 16–1 The external female genitalia.

The major vestibular glands are known as Bartholin’s glands, or vulvovaginal glands. These pea-sized glands correspond to the male Cowper’s glands. Each Bartholin’s gland lies posterolaterally to the vaginal orifice. During sexual intercourse, a watery fluid is secreted that serves as a vaginal lubricant.

Inferiorly, the labia minora unite at the posterior commissure to form the fourchette. The perineum is the area between the fourchette and the anus.

The hymen is a circular fold of tissue that partially occludes the vaginal introitus. There are marked variations in its size, as well as in the number of openings in it. The vaginal introitus is the border between the external and internal genitalia and is located in the lower portion of the vestibule.

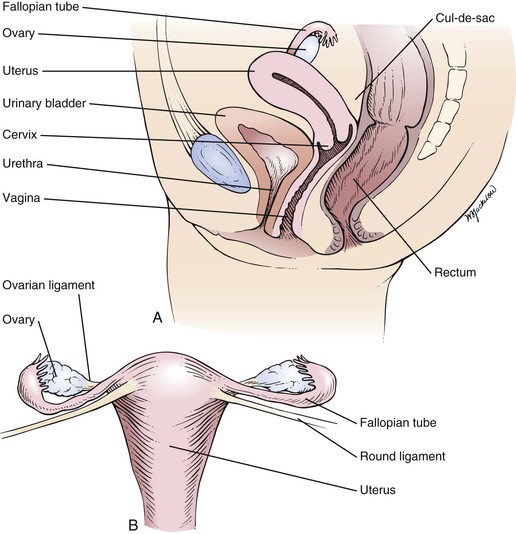

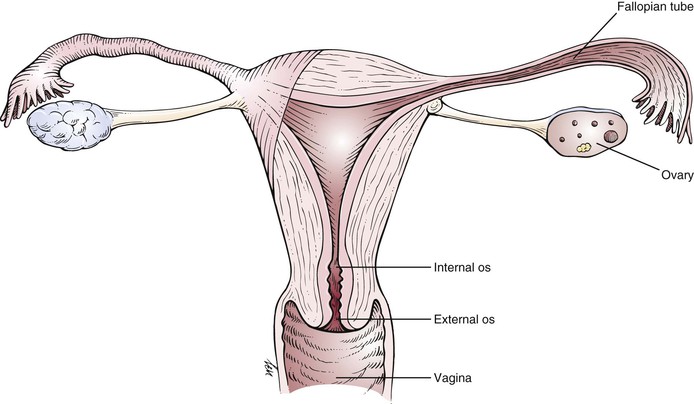

The internal genitalia are shown in Figure 16-2. The vagina is a muscularly walled, hollow canal that passes upward and slightly backward, at a right angle to the uterus. The vagina lies between the urinary bladder anteriorly and the rectum posteriorly. The vaginal walls are lined by transverse rugae, or folds. The lower portion of the cervix projects into the upper portion of the vagina and divides it into four fornices. The anterior fornix is shallow and is just posterior to the bladder. The posterior fornix is deep and is just anterior to the rectovaginal pouch, known as the cul-de-sac (pouch) of Douglas, and the pelvic viscera lie immediately above this pouch. The lateral fornices contain the broad ligaments. The fallopian tubes and ovaries may be palpated in the lateral fornices. The superficial cells of the vagina contain glycogen, which is acted on by the normal vaginal flora to produce lactic acid. This is in part responsible for the resistance of the vagina to infection.

Figure 16–2 A, Cross-sectional view of the internal female genitalia. B, Frontal view of the uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries.

The arterial supply to the vagina is derived from the internal iliac, uterine, and middle hemorrhoidal arteries. The lymphatic channels of the lower third of the vagina drain into the inguinal nodes. The lymphatic channels of the upper two thirds enter the hypogastric and sacral nodes.

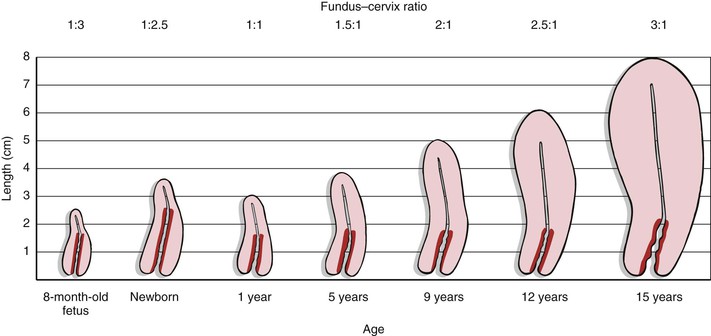

The uterus is a hollow muscular organ with a small central cavity. The lower end is the cervix, and the upper portion is the fundus. The size of the uterus is different during various stages of life. At birth, the uterus is only 3 to 4 cm long. The adult uterus is 7 to 8 cm long and 3.5 cm wide, with an average wall thickness of 2 to 3 cm. The growth of the uterus and the relationship of the size of the fundus to the size of the cervix are shown in Figure 16-3.

Figure 16–3 Growth of the uterus and changes in the fundus–cervix ratio with development. The darker red area represents the length of the cervix.

The triangular uterine cavity is 6 to 7 cm in length and is bounded by the internal cervical os inferiorly and the entrances of the fallopian tubes superiorly. Normally, the long axis of the uterus is bent forward on the long axis of the vagina. This is anteversion. The fundus is also bent slightly forward on the cervix. This is anteflexion.

The uterus is freely mobile and is located centrally in the pelvic cavity. It is supported by the broad and uterosacral ligaments, as well as by the pelvic floor. The peritoneum covers the fundus anteriorly down to the level of the internal cervical os. Posteriorly, the peritoneum covers the uterus down to the pouch of Douglas. The function of the uterus is childbearing. Figure 16-4 is a detailed anatomic representation of the uterus.

Figure 16–4 Anatomy of the uterus.

The cervix is the vaginal portion of the uterus. The greater portion of the cervix has no peritoneal covering. The cervical canal extends from the external cervical os to the internal cervical os, where it continues into the cavity of the fundus. The external cervical os in women who have not given birth vaginally is small and circular. In women who have had vaginal deliveries, the external cervical os is linear or oval.

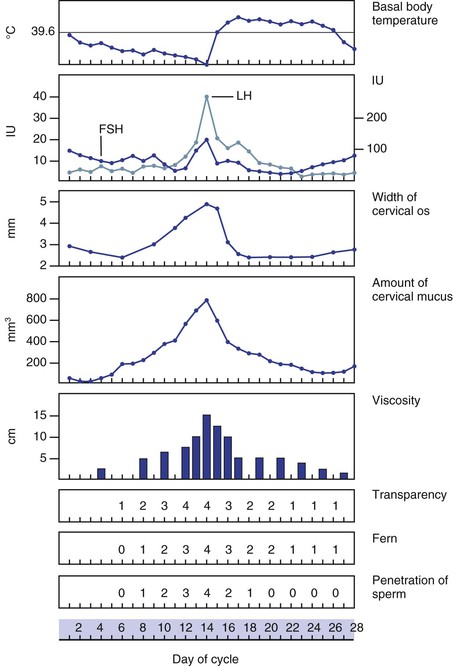

With increasing levels of estrogens, the external cervical os begins to dilate, and cervical mucous secretion becomes clear and watery. With high levels of estrogens, cervical mucus, when placed between two glass slides that are then pulled apart, can be stretched 15 to 20 cm before breaking. This property of cervical mucus—the ability to be drawn into a fine thread—is termed spinnbarkeit. When cervical mucus is allowed to dry on a glass slide and is examined under low power by light microscopy, a fern pattern made up of salt crystals may be seen. Spinnbarkeit and ferning reach a maximum at the midpoint of the menstrual cycle. Sperm can more easily penetrate mucus with these characteristics.

The blood supply to the uterus comes from the uterine and ovarian arteries. The lymphatic vessels of the fundus enter into the lumbar nodes.

The fallopian tubes, or oviducts, enter the fundus at its superior aspect. They are small muscular tubes that extend outward into the broad ligament toward the pelvic wall. The other end of the oviduct opens into the peritoneal cavity near the ovary. These endings are surrounded by fringe-shaped projections called fimbriae. The primary function of the fallopian tube is to provide a conduit for the egg to convey it from the corresponding ovary to the uterus, a trip that takes several days. Sperm traverse the oviduct in the opposite direction, and it is usually in the oviduct that fertilization takes place.

The ovaries are almond-shaped structures about 3 to 4 cm long and are attached to the broad ligament. The primary functions of the ovary are oogenesis and hormone production.

The ovaries, fallopian tubes, and supporting ligaments are termed the adnexa.

The female reproductive system is under the influence of the hypothalamus, whose releasing factors control the secretion of the anterior pituitary gonadotropic hormones: follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone. In response to these hormones, the ovarian Graafian follicle secretes estrogens and discharges its ovum. After ovulation, the ovarian follicle is termed the corpus luteum, which secretes estrogens and progesterone. With the secretion of progesterone, the basal body temperature rises. This is a reliable sign of ovulation. Under the influence of the ovarian hormones, the uterus and breasts undergo the characteristic changes of the menstrual cycle.

If pregnancy does not occur, the corpus luteum regresses, and the level of ovarian hormones begins to fall. At this time, before menstruation, many women have symptoms of weakness, depression, and irritability. Breast tenderness is also common. These symptoms are termed premenstrual syndrome. Approximately 5 days after the fall in the level of hormones, the menstrual period begins. Menstrual fluid throughout the 5-day period measures approximately 50 to 150 mL, only half of which is blood; the remainder is mucus. Because menstrual blood does not contain fibrin, it does not clot. When the menstrual flow is heavy, as it is on days 1 to 2, “clots” may be described. These clots are not fibrin clots but are combinations of red blood cells, glycoproteins, and mucoid substances that are believed to form in the vagina rather than in the uterine cavity.

Some of the hormone-dependent changes related to the menstrual cycle are shown in Figure 16-5.

Figure 16–5 Physiologic changes associated with the menstrual cycle. The numbers 0 to 4 indicate an increasing characteristic of cervical mucus. Notice that ferning, transparency, and penetration of sperm are maximal at midcycle. FSH, Follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone.

Approximately 1.5 years before puberty, gonadotropins are measurable in the urine. The ovaries enter a period of rapid growth at, on average, 8 to 9 years of age, which marks the onset of puberty. Secretion of estrogens begins to increase rapidly at approximately 11 years of age. Concomitant with estrogen production, the sexual organs begin to mature. During puberty, the secondary sex characteristics begin to develop. The breasts enlarge, hair develops on the pubis, the vulva enlarges, the labia minora become pigmented, and the body contour changes. Puberty lasts for approximately 4 to 5 years. The first menstrual cycle, called menarche, occurs at the end of puberty at approximately 12.5 years of age. There is, however, a wide variation in the age at menarche. The cycles continue approximately every 28 days, with a flow lasting 3 to 5 days. The first day of the period is designated the first day of the cycle. It is rare for a woman to be absolutely regular, and cycles of 25 to 34 days are considered normal.

At the time of menarche, the menstrual cycle is usually anovulatory3 and irregular. After 1 to 2 years, ovulation begins. After stabilization of the menses, ovulation occurs approximately midcycle in a woman with a regular cycle.

Menopause marks the ends of menstruation. Menopause is defined as the last uterine bleeding induced by ovarian function. It usually occurs between 45 and 55 years of age. Ovulation and corpus luteum formation no longer occur, and the ovaries decrease in size. The period after menopause is termed postmenopausal.

Review of Specific Symptoms

The most common symptoms of female genitourinary disease are as follows:

Abnormal Vaginal Bleeding

Ask these questions of any woman with abnormal vaginal bleeding:

“How long have you noticed the vaginal bleeding?”

“Do you use contraceptives?” If yes,

“What types of contraceptives do you use?”

“What is the duration of your menstrual flow?”

“How many tampons or napkins do you use on each day of your flow?”

“Are there any clots of blood?”

“Have you noticed bleeding between your periods?”

“Do you have abdominal pain during your periods?”

“Do you have hot flashes? Cold sweats?”

“Do you have children?” If yes, “When was your last one born?”

“Do you think you might be pregnant?”

“Are you under any unusual emotional stress?”

“Have you noticed a change in your vision?”

“Have you had any headaches? Nausea? Change in hair pattern? Milk discharge from your nipples?”

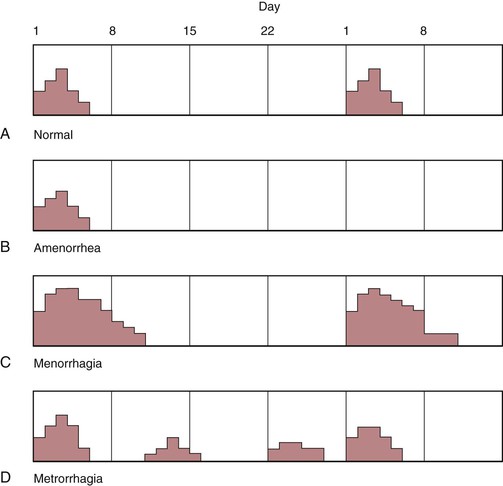

Abnormal uterine bleeding, also known as dysfunctional uterine bleeding, includes amenorrhea, menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, and postmenopausal bleeding. Amenorrhea is the cessation or nonappearance of menstruation. Before puberty, amenorrhea is physiologic, as it is during pregnancy and after menopause. In primary amenorrhea, menstruation has never occurred; in secondary amenorrhea, menstruation has occurred but has ceased, as in pregnancy. Long-distance joggers, patients with anorexia, or any woman with abnormally low body fat may have secondary amenorrhea. Diseases of the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, ovary, uterus, and thyroid gland are associated with amenorrhea. Galactorrhea, or milk discharge from the nipples, occurs in many individuals with pituitary tumors. Chronic disease is also frequently associated with secondary amenorrhea.

Menorrhagia is excessive bleeding at the time of the menstrual period. The flow may be increased, the duration may be increased, or both may occur. The number of pads or tampons a patient uses each day of the cycle helps quantify the flow. Menorrhagia in some cases may be associated with blood disorders such as leukemia, inherited clotting abnormalities, and decreased platelet states. Uterine fibroids are a leading cause of menorrhagia. Menorrhagia secondary to fibroids is related to the large surface area of the endometrium from which bleeding occurs.

Metrorrhagia is uterine bleeding of normal amount at irregular, noncyclic intervals. Foreign bodies such as intrauterine devices, as well as uterine or cervical polyps, and ovarian and uterine tumors, can cause metrorrhagia. Often there is increased bleeding between cycles as well as heavier periods; this is termed menometrorrhagia.

Bleeding that occurs more than 6 to 8 months after menopause is termed postmenopausal bleeding. Because many cancers of reproductive organs may present with bleeding, any postmenopausal bleeding must be investigated. Uterine fibroids or tumors of the cervix, uterus, or ovary may be responsible. Lower tract disease, such as vaginal atrophy, or even urinary tract problems may present with postmenopausal bleeding.

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea, or painful menstruation, is a common symptom. It is often difficult to define as abnormal because many healthy women have some degree of menstrual discomfort. In most women, these cramps subside soon after the commencement of the menstrual flow. There are two types of dysmenorrhea: primary and secondary. Primary dysmenorrhea is far more common. It begins shortly after menarche, is associated with colicky uterine contractions, and occurs with every period. Childbirth frequently alleviates this state permanently. Secondary dysmenorrhea is caused by acquired disorders within the uterine cavity (e.g., intrauterine devices, polyps, or fibroids), obstruction to flow (e.g., cervical stenosis), or disorders of the pelvic peritoneum (e.g., endometriosis4 or pelvic inflammatory disease). It usually occurs after several years of painless periods. Regardless of its cause, dysmenorrhea is described as intermittent, crampy pain accompanying the menstrual flow. The pain is felt in the lower abdomen and back, sometimes radiating down the legs. In severe cases, fainting, nausea, or vomiting may occur.

Masses or Lesions

Masses or lesions of the external genitalia are common. They may be related to venereal diseases, tumors, or infections. Ask these questions of any woman with a lesion on the genitalia:

“When did you first notice the mass (lesion)?”

“Has it changed since you first noticed it?”

Syphilis may result in a chancre on the labia. Often unnoticed, it is a small, painless nodule or ulcer with a sharply demarcated border. Small, acutely painful ulcers may be chancroid or genital herpes. A patient with an abscess of Bartholin’s gland may present with an extremely tender mass in the vulva. Benign tumors, such as venereal warts (condylomata acuminata), and malignant conditions manifest as a mass on the external genitalia.

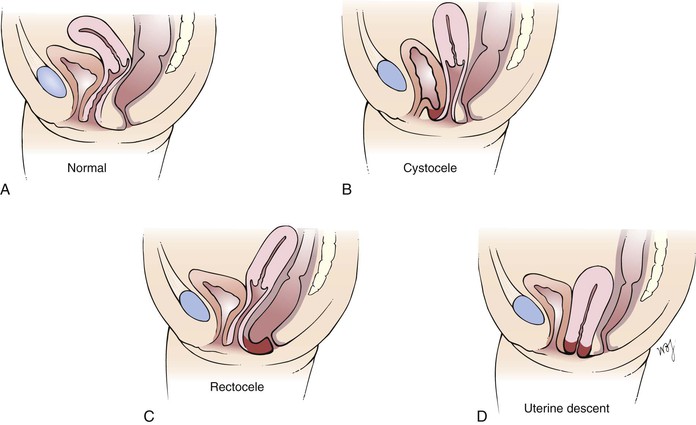

Some affected patients complain of a sensation of fullness or mass in the pelvis as a result of pelvic relaxation. Pelvic relaxation refers to the descent or protrusion of the vaginal walls or uterus through the vaginal introitus. This is caused by a weakening of the pelvic supports. The anterior vaginal wall can descend, producing a cystocele that triggers urinary symptoms such as frequency and stress incontinence. The posterior vaginal wall can descend, producing a rectocele, which triggers bowel symptoms such as constipation, tenesmus, or incontinence. The uterus can also descend, which results in uterine prolapse. In the most severe state, the uterus may lie outside the vulva with complete vaginal inversion, a condition known as procidentia. The consequences of pelvic relaxation are discussed further in the section titled “Clinicopathologic Correlations” later in this chapter.

Vaginal Discharge

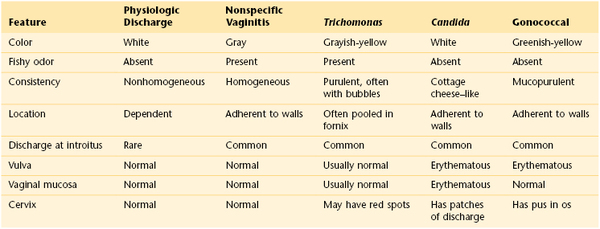

Vaginal discharges, also known as leukorrhea, are common. Is there an associated foul odor? Although a whitish discharge is often normally present, a fetid discharge often indicates a pathologic problem. The most common pathologic odor, associated with bacterial vaginosis, is a foul, fishy odor related to the volatilization of amines that are produced by anaerobic metabolism of a variety of bacteria. Is itching also present? Women with moniliasis (candidiasis) complain of intense pruritus and a white, dry discharge that looks like cottage cheese. Has the woman recently taken any medications, such as antibiotics? Antibiotics change the normal vaginal flora, and an overgrowth of Candida may result. Table 16-1 summarizes the important characteristics of vaginal discharge.

Vaginal Itching

Vaginal itching is associated with monilial infections, glycosuria,5 vulvar leukoplakia, and any condition that predisposes a woman to vulvar irritation. Pruritus may also be a symptom of psychosomatic disease.

Abdominal Pain

Ask the following questions, in addition to those listed in Chapter 14, The Abdomen, of any woman with abdominal pain:

“Have you ever had any type of venereal disease?”

“Is the pain related to your menstrual cycle?” If yes, “At what time in your cycle does it occur?”

Abdominal pain may be acute or chronic. Is the patient pregnant? Acute abdominal pain may be a complication of pregnancy. Spontaneous abortion, uterine perforation, and ectopic tubal pregnancy all are life-threatening situations. Acute inflammation by gonococci of the fallopian tubes and ovary, salpingo-oophoritis, can produce intense lower abdominal pain. Acute lower abdominal pain localized to one side that occurs at the time of ovulation is termed mittelschmerz. This pain is related to a small amount of intraperitoneal bleeding at the time of ovum release. Urinary tract infection may also cause acute pain. Patients with urinary tract infections usually have associated urinary symptoms of burning sensation or frequency.

Chronic abdominal pain may result from ectopic endometrial tissue, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease of the fallopian tubes and ovaries, and pelvic muscle relaxation with protrusion of the bladder, rectum, or uterus.

Dyspareunia

Dyspareunia is pain during or after sexual intercourse. Dyspareunia may be physiologic or psychogenic. Infections of the vulva, introitus, vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries have been associated with dyspareunia. Tumors of the rectovaginal septum, uterus, and ovaries have been described in patients who experienced painful sexual intercourse. Dyspareunia is often present in the absence of a physiologic disorder. A history of painful pelvic examinations and a fear of pregnancy are common in these patients. Women may have “penetration anxiety” until they are assured that the vagina can be penetrated by a penis. In these individuals, such anxiety may lead to vaginismus, a condition of severe pelvic pain and spasm when the labia are merely touched. In other women, dyspareunia may develop during times of stress or emotional conflict. The examiner can obtain valuable information by asking, “What else is going on in your life now?” Dryness of the vagina and labia may cause irritation that can result in dyspareunia. Vaginal lubrication, especially during sexual intercourse may be extremely helpful.

Changes in Hair Distribution

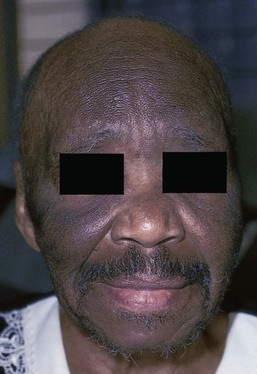

Hair loss or change in hair distribution may occur during certain states of hormonal imbalance. Hirsutism is an excessive growth of hair on the upper lip, face, earlobes, upper pubic triangle, trunk, or limbs. Virilization is extensive hirsutism associated with receding temporal hair, a deepening of the voice, and clitoral enlargement. Increased androgen production by the adrenal glands or ovaries may be responsible for these phenomena. Tumors of the ovary are commonly associated with amenorrhea, rapidly developing hirsutism, and virilization. Polycystic ovarian disease is the most common ovarian cause of hirsutism, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, infertility, acne, and obesity. Figure 16-6 shows the increased hair growth on the chest of a 34-year-old woman with polycystic ovary syndrome. She also presented with amenorrhea and obesity. Figure 16-7 shows the face of a 68-year-old woman with an androgen-secreting ovarian tumor. Note the male-pattern baldness and the facial hair. This patient also had clitoral enlargement.

It is important to determine whether the patient is taking any medications. Several drugs such as cyclosporine, minoxidil, diazoxide, penicillamine, and glucocorticoids have the unexpected side effect of causing diffuse hair growth on the face. Figure 16-8 shows such growth in a 42-year-old woman who was taking minoxidil for hypertension. This drug is now used as a topical treatment for androgenic alopecia. The pathophysiologic process behind the increased hair growth is unknown.

Hair loss, or alopecia, is a distressing problem. Many drugs may have a profound effect on hair growth. The interviewer must inquire whether the patient has taken any chemotherapeutic agents or has been exposed to radiation. Different areas of the head seem to respond differently to androgens. The top and front of the scalp respond to increased androgen production by hair loss, whereas the face responds with increased hair growth. Has the patient been dieting? Because hair has a high metabolic rate, crash diets and infectious diseases reduce the nutrients available for hair growth, and secondary alopecia may result.

Changes in Urinary Pattern

Changes in the patterns of urination are common. Chapter 15, Male Genitalia and Hernias, reviews many of the symptoms associated with changes in the urinary pattern. These symptoms may occur in women as well.

Stress incontinence is urinary incontinence that occurs with straining or coughing. Stress incontinence is more common among women than among men. The female urinary bladder and urethra are maintained in position by several muscular and fascial supports. It has been postulated that estrogens may be responsible, at least in part, for a weakening of the pelvic support. With aging, the support of the bladder neck, the length of the urethra, and the competence of the pelvic floor are decreased. Repeated vaginal deliveries, strenuous exercise, and chronic coughing increase the chance for stress incontinence. Ask an affected patient these questions:

“Do you lose your urine on straining? Coughing? Lifting? Laughing?”

“Do you lose your urine constantly?”

“Do you lose small amounts of urine?”

“Are you aware of a full bladder?”

“Do you have to press on your abdomen to void?”

“Are you aware of any weakness in your limbs?”

Patients with pure stress incontinence describe urine loss without urgency that occurs during any activity that momentarily increases intra-abdominal pressure. Although stress incontinence is common among women, it is important to rule out other types of incontinence, such as neurologic, overflow, and psychogenic. Neurologic incontinence may result from cerebral dysfunction, spinal cord disease, and peripheral nerve lesions. Multiple sclerosis is a chronic relapsing neurologic disorder causing urinary incontinence. Most affected individuals suffer from an episode of temporary loss of vision as an early symptom. Overflow incontinence occurs when the pressure in the bladder exceeds the urethral pressure in the absence of bladder contraction. This may occur in patients with diabetes and an atonic bladder. In psychogenic incontinence, individuals have been known to urinate in bed at night to “warm” themselves or during the daytime in group settings to draw attention to themselves.

Infertility

Infertility may result from failure to ovulate, called anovulation, or from inadequate function of the corpus luteum. Both these conditions can occur in women with cyclic menstrual bleeding. Therefore having a period does not indicate fertility. A woman with the symptom of infertility should be asked these questions:

“Do you have regular menstrual periods?”

“Have you kept a chart of your basal body temperature?”

“Have you ever had venereal disease?”

Charting basal body temperature is a reliable method for detecting ovulation. Infections caused by Neisseria gonococci or Chlamydia trachomatis in a woman may lead to salpingo-oophoritis, with scarring of the fallopian tubes and infertility. Hypothyroidism is a well-known cause of infertility.

General Suggestions

Even in the absence of specific symptoms, all women, regardless of age, should be asked several important questions. The answers to the following questions provide a complete gynecologic, obstetric, and reproductive history. The first group of questions is related to the gynecologic history and menstrual cycle:

“At what age did you start to menstruate?”

“How often do your periods occur?”

“For how many days do you have menstrual flow?”

“How many pads or tampons do you use each day of your flow?”

The catamenia refers to the menstrual history and summarizes the age at menarche, the cycle length, and the duration of flow. If a woman reached menarche at age 12 years and has had regular periods every 29 days lasting for 5 days, the catamenia can be summarized as “CAT 12 × 29 × 5.” The date of the last menstrual period can be abbreviated as, for example, “LMP: August 10, 2013.”

Recurrent, midcyclic symptoms associated with the menstrual period, such as breast tenderness, bloating, and so forth, are termed molimina. The presence of molimina is correlated with ovulation, although not all women experience symptoms when ovulation occurs. Therefore molimina are specific but nonsensitive signs of ovulation.

The next group of questions is related to the obstetric history:

If the woman has been pregnant, ask the following questions:

“What was the outcome of your pregnancy(ies)?”

“How many full-term pregnancies have you had?”

“Have you had any children born prematurely?”

“How many living children do you have?”

The obstetric history includes the number of pregnancies, known as gravidity, and the number of deliveries, known as parity. If a woman has had three full-term infants (born at 37 weeks or more of gestation), two premature infants (born at less than 37 weeks of gestation), one miscarriage (or abortion), and four living children, her obstetric history can be summarized as “para 3-2-1-4.” An easy way to remember this four-digit parity code is with the mnemonic “Florida Power And Light,” which stands for full term, premature, abortions (miscarriages), living. The woman in this example is gravida 6.

When asking about abortions or miscarriages, it is advisable to keep in mind that in the United States, and in some other countries, the word “abortion” itself may be charged with many religious, political, and cultural feelings in different women. Maintain sensitivity while asking the question, reminding the patient that the medical term “abortion” means loss of any pregnancy, including voluntary terminations, ectopic pregnancy, or spontaneous miscarriage.

When asking a woman about the date of her last menstrual period, never assume that menopause has occurred. Women of any age should be asked when their last menstrual period occurred. Allow the patient to say that she has not had a period in, for example, 12 years.

A careful sexual history is important. Chapter 1, The Interviewer’s Questions, provides several ways of broaching the topic. The interviewer might start by asking, “Are you satisfied with your sexual activity?” It is important for the examiner to know whether the woman practices heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual activities. Is the patient married? How many times? For how long? Are there other sexual partners? If the patient is not married, is she currently having sexual relationships? While lesbians may not need contraception, it is important to address the issue of birth control regardless of sexual orientation. What type of birth control is being used? It is important to ask all sexually active women the following:

“How easily can you reach an orgasm or climax?”

“How strong is your sex drive?”

“How easily are you sexually aroused?”

Always determine whether the patient’s mother was given diethylstilbestrol (DES)6 during her pregnancy.

Use words that the patient will understand. It may be necessary to use such terms as “lips” to refer to the labia or “privates” to refer to the genitalia.

Effect of Infertility on the Woman

The problem of infertility is not new. From ancient times, cultures have practiced fertility rites to ensure the continuation of their people. Many societies considered a woman’s worth in terms of her ability to have children. The “barren woman” was frequently banished.

The average time it takes for a woman to conceive is 4 to 5 months. The American Fertility Society defines infertility as the inability to conceive “after 1 year of regular coitus without contraception.” During this time, more than 80% of women conceive. After 3 years of regular sexual intercourse, 98% of women become pregnant.

It has been estimated that approximately one of every six couples in the United States has some problem with fertility. Infertility should be considered a problem of both men and women. It was previously thought that infertility was functional (no demonstrable organ disorder) in 30% to 50% of all cases, but it is now recognized that more than 90% of infertile couples have a pathologic cause. However, only approximately 50% of these couples achieve pregnancy. Fifty percent of infertility is related to a female problem,7 30% to a male problem,8 and 20% to a combined problem.

Infertility is one of several important developmental crises of adult life. The effect of infertility on a woman can be severe. The influence of the higher nervous system on ovulation is well known but only partially understood. When a woman is told that she is infertile, she may be shocked and distressed about the loss of an important function of her body. This psychological injury lasts for variable amounts of time. Often the woman feels defective or inadequate. This extends to her interactions with others, in addition to her sexual function. Her attitude toward her job may change; her work productivity may decline. There may be a significant decrease in sexual desire. Depression, loss of libido, and concern over whether conception will ever occur combine to make sex a less pleasurable activity and decrease the possibility of normal ovulation. A period of mourning and frustration usually occurs.

Often the woman becomes preoccupied with her menstrual periods. When will the next one come? Is she pregnant? Did she have any symptoms of ovulation? When the next menstrual cycle occurs, the woman may suffer further grief.

The infertile woman may fear that her partner will resent her, and she may feel alienated from him. She may experience jealousy and resentment toward friends or relations who have children. Her infertility lowers her self-esteem and may make her feel that she is unfit to be a parent.

Regardless of the cause of infertility, the treatment must work to lessen the psychological side effects. Both partners must be encouraged to communicate. Education regarding the physical problem is important throughout the medical work-up. Communication between the partners and the physician is paramount. The patient needs to be protected from her own insecurities and treated with empathy and compassion.

In some women, psychogenic factors may be the sole cause of infertility. Such factors may act at various phases in the reproductive process. These women may have immature personalities and fear the responsibilities of motherhood. They use their infertility as a defense mechanism. In other cases, emotional conflicts may lead to somatic symptoms and signs. Vaginismus is the most common psychosomatic disorder causing infertility. In this condition, the introitus may become so constricted that it inhibits the penis from entering. Vaginismus protects the patient from conception. Many of these women view sexual intercourse as exploitative and degrading. Intercourse is feared because it is painful. These patients do well with psychotherapy that allows them to express their fears about intercourse, genitalia, and childbearing.

Physical Examination

The equipment necessary for the examination of the female genitalia and rectum consists of a vaginal speculum, lubricant, gloves, liquid media for cytology (which has replaced the Pap smear), cervical scraper and brush, cotton-tipped applicators, glass slides, culture media (as appropriate), tissues, and a light source. A mirror is often handy so that the patient can participate in the examination.

General Considerations

Unlike most other parts of the physical examination, the pelvic examination is often viewed with apprehension by the patient. This is frequently related to a previous bad experience. An examination performed slowly and gently with adequate explanations goes a long way in developing a good doctor-patient relationship. Communication is the key to a successful pelvic examination. The examiner should talk to the patient and tell her exactly what is going to be done. Eye contact is also necessary to decrease the patient’s anxiety. The patient’s ability to relax enables a more accurate and less traumatic examination.

If the examiner is a man, he should examine the patient’s genitalia in the presence of a female attendant. Although not required by law in all states, the presence of a female attendant is important for assistance, as well as for medicolegal considerations, especially when the patient appears overly upset or seductive. At times, the patient may request that a family member be present. The examiner should grant such a request if no other attendant is available.

Throughout the world, various patient positions are preferred to facilitate the pelvic examination. These include the woman’s lying on her back on an examining table, lying in bed on her left side, lying on her back in bed with her legs abducted, and sitting upright in a chair with her legs abducted. In the United States, the woman usually lies on her back on an examination table with her feet in heel rests, the dorsolithotomy position. This position can be uncomfortable and may be viewed by some as demeaning.

Preparation for the Examination

The patient should be instructed to empty her bladder and bowels before the examination. The patient is assisted onto an examination table with her buttocks placed near its edge. The heel rests of the table are extended, and the patient is instructed to place her heels in them. If possible, some cloth should be placed over the rests. Alternatively, the patient can be given plastic foam booties to protect her feet from cold metal heel rests. Shortening the heel rest brackets helps the woman bend her knees to lower the position of the cervix. An older patient with osteoarthritis may need the heel rests to be longer because she may have limited hip and knee motion. Offer the patient a mirror that she can use to observe the examination.

The head of the examination table should be elevated so that eye contact between the physician and the patient can occur. A sheet is usually draped over the lower abdomen and knees of the patient. Some patients prefer not to have the sheet used. The patient should be asked her preference.

The knees are drawn up sufficiently to relax the abdominal muscles as the thighs are abducted. Ask the patient to let her legs fall to the sides or to drop her knees to each side. Never tell a patient to “spread her legs.”

Gloves should be worn for the examination of the female genitalia. The examiner should be seated on a stool between the legs of the patient. Good lighting, including a light source directed into the vagina, is essential.

The examination of the female genitalia consists of the following:

Inspection and Palpation of External Genitalia

Inspect the External Genitalia and Hair

To make the woman more comfortable during inspection of the external genitalia, it is often useful to touch the patient. Tell the patient that you are going to touch her leg. Use the back of your hand.

The external genitalia should be inspected carefully. The mons veneris is inspected for lesions and swelling. The hair is inspected for its pattern and for pubic lice and nits. The skin of the vulva is inspected for redness, excoriation, masses, leukoplakia, and changes in pigmentation. Lesions should be palpated for tenderness.

Lichen sclerosus, previously known as kraurosis vulvae, is a relatively common condition in which the genital skin shows a uniform reddened, smooth, shiny, almost transparent appearance. It is a destructive inflammatory condition with a predilection for genital skin. It is much more common in women, although it can be seen in men with involvement of the glans penis and foreskin. Whitish atrophic patches of thin skin are typical, as is fine crinkling of the skin. Pruritus is a common symptom, and the fragile skin is susceptible to secondary infection. Although most common in white and Latino postmenopausal women, lichen sclerosus may be seen in patients of all ages. It is rare in African-American women. Lichen sclerosus should be thought of as a premalignant lesion because one complication is the development of squamous cell carcinoma. Figure 16-9 shows an early stage of lichen sclerosus in a female patient. Notice the resorption of the labia minora; the clitoris is preserved. Figure 16-10 shows a later stage in another patient. Notice the classic whitish crinkling of the skin and the resorption of the labia and clitoris. Figure 16-11 shows vulvar squamous cell carcinoma with the background of lichen sclerosus in another patient.

Figure 16–9 Lichen sclerosus, early stage.

Inspect the Labia

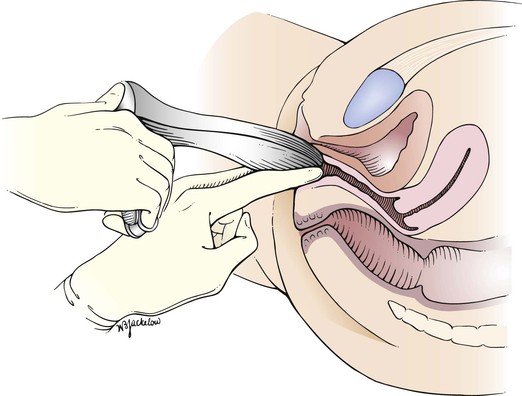

Tell the patient that you are now going to touch and spread the labia, as demonstrated in Figure 16-12. Inspect the vaginal introitus.

Figure 16–12 Technique for inspecting the labia.

The labia minora may show wide variation in size and shape; they may be asymmetrical. On occasion, yellowish-white, asymptomatic papules may be seen over the inner labia minora. These are called Fordyce’s spots and are normal; they represent ectopic sebaceous glands. Figure 16-13 shows Fordyce’s spots. Ectopic sebaceous glands are also common in the mouth (see Figure 9-18) and on the shaft of the penis (see Figure 15-11).

Figure 16–13 Fordyce’s spots of the labia.

Inflammatory lesions, ulceration, discharge, scarring, warts, trauma, swelling, atrophic changes, and masses are noted. Figures 16-14 and 16-15 show condylomata acuminata of the labia.

Figure 16–14 Condylomata acuminata.

Figure 16–15 Condylomata acuminata.

Inspect the Clitoris

Inspect the clitoris for size and lesions. The clitoris is normally 3 to 4 mm in size.

Inspect the Urethral Meatus

Is pus or inflammation present? If pus is present, determine its source. Dip a cotton-tipped applicator into the discharge, send it to the laboratory for culture and spread some of the sample on a microscope slide for later evaluation. Are any masses present?

Inspect the Area of Bartholin’s Glands

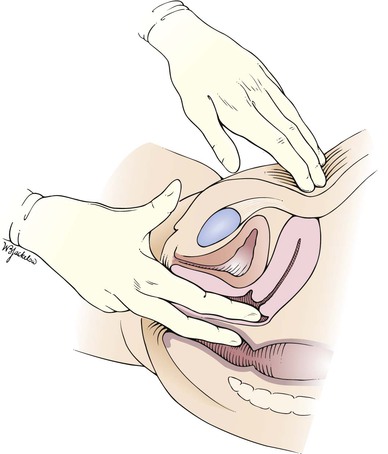

Tell the patient that you are going to palpate the glands of the labia. With a moistened or lubricated glove, palpate the area of the right gland (at the 7 to 8 o’clock position) by grasping the posterior portion of the right labia between your right index finger in the vagina and your right thumb on the outside, as demonstrated in Figure 16-16. Is any tenderness, swelling, or pus present? Normally, Bartholin’s glands can be neither seen nor felt. Use your left hand to examine the area of the left gland (at the 4 to 5 o’clock position).

Figure 16–16 Technique for palpation of Bartholin’s glands.

Figure 16-17 shows an abscess in the left Bartholin’s gland.

Figure 16–17 Bartholin’s gland abscess.

Inspect the Perineum

The perineum and anus are inspected for masses, scars, fissures, and fistulas. Is the perineal skin reddened? The anus should be inspected for hemorrhoids, condylomata, irritation, and fissures.

Test for Pelvic Relaxation

While you gently separate the labia widely and depress the perineum, ask the patient to bear down or cough. If vaginal relaxation is present, ballooning of the anterior or posterior walls may be seen. Bulging of the anterior wall is associated with a cystocele; bulging of the posterior wall is indicative of a rectocele. If stress incontinence is present, the coughing or bearing down may trigger a spurt of urine from the urethral orifice.

Examination with Speculum

Preparation

The speculum examination entails inspecting the vagina and cervix. There are several types of specula. The metal Cusco, or bivalve, speculum is the most popular. This speculum consists of two blades or bills that are introduced closed into the vagina and are then opened by squeezing the handle mechanism. The vaginal walls are held apart by the bills, and adequate visualization of the vagina and cervix is achieved. There are basically two types of bivalve specula: Graves’ and Pedersen’s. Graves’ speculum is more common and is used for most adult women. The bills are wider and are curved on the sides. Pedersen’s speculum has narrower, flat bills and is used for women with a small introitus. The plastic, disposable bivalve speculum is becoming more common. A disadvantage to its use is the loud click made as the lower bill is disengaged during removal from the vagina. If a plastic speculum is used, the patient should be informed that this sound will occur. Check the bills to make sure that there are no rough edges.

Before using the speculum in a patient, practice opening and closing it. If the patient has never had a speculum examination, show the speculum to her. You should warm the speculum with warm water and then touch it to the dorsum of your hand to ensure that the temperature is suitable. A small amount of jelly lubricant may be used, especially since liquid-based cervical cytologic examination has replaced the glass slide Pap test, and gonorrhea and Chlamydia testing by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)9 has replaced most bacterial and fungal cultures. Tell the patient that you are now going to perform the speculum part of the internal examination.

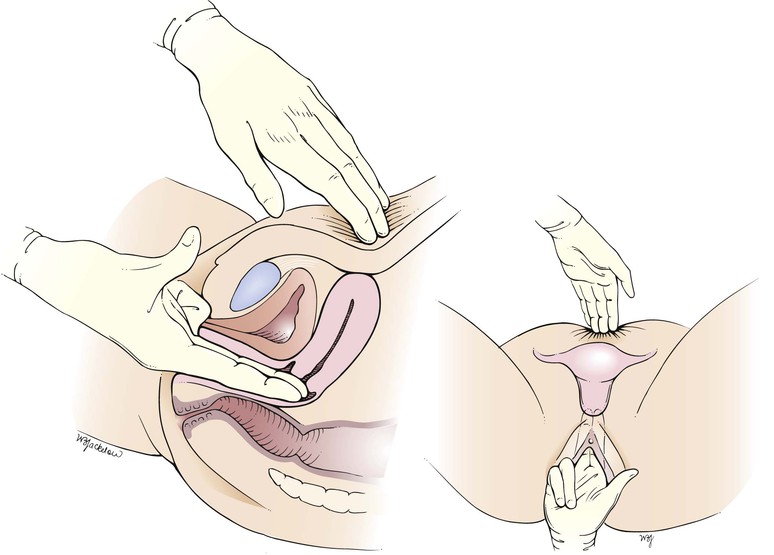

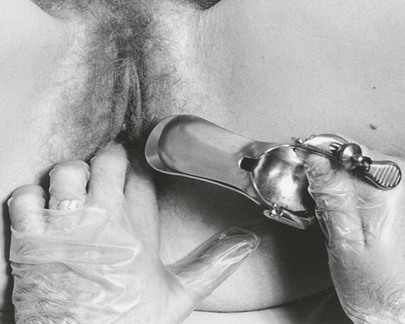

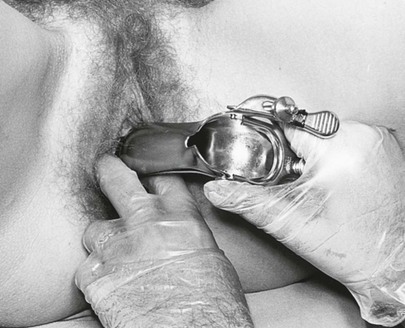

Technique

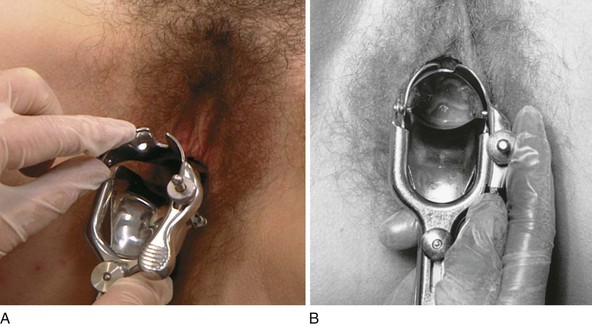

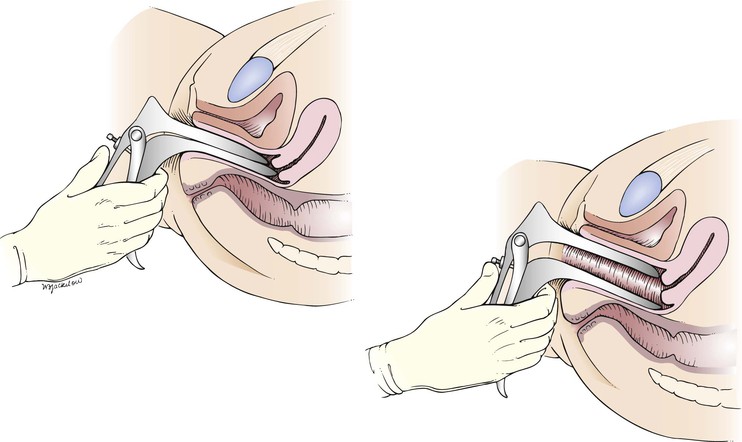

While the examiner’s left index and middle fingers separate the labia and firmly depress the perineum, the closed speculum, held in the examiner’s right hand, is introduced slowly into the introitus at an oblique angle of 45 degrees from the vertical over the examiner’s left fingers. This procedure is demonstrated in Figures 16-18 and 16-19 and is diagrammed in Figure 16-20. Do not introduce the speculum vertically, because injury to the urethra or meatus may occur.

Figure 16–18 Technique for insertion of the vaginal speculum. Note the examiner’s fingers pressing downward on the perineum.

Figure 16–19 Technique for insertion of the vaginal speculum. Note that the speculum rides over the examiner’s fingers, avoiding contact with the external urethral meatus and clitoris.

Figure 16–20 Cross-sectional view of the speculum examination.

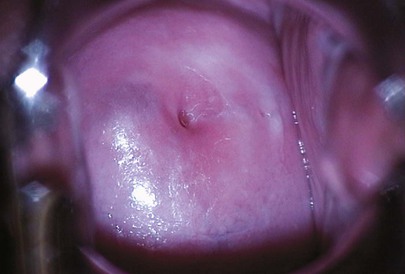

Inspect the Cervix

The speculum is introduced to full depth. When it is inserted completely, the speculum is rotated to the horizontal position, with the handle now pointing downward, and is opened slowly. With the bills open, the vaginal walls and cervix can be visualized. The cervix should rest within the bills of the speculum. This is demonstrated in Figure 16-21 and diagrammed in Figure 16-22. To keep the speculum open, the set screw can be tightened. If the cervix is not immediately seen, gently turn the bills in various directions to expose the cervix. The most common reason for not visualizing the cervix is failure to insert the speculum far enough before opening it.

Figure 16–21 Technique for inspecting the cervix. A, Opening of the speculum bills after the speculum has been fully inserted and rotated to the transverse position. B, Internal view of the cervix when the speculum is correctly inserted.

Figure 16–22 Cross-sectional view illustrating the position of the speculum during inspection of the cervix.

Inspect the cervix for color, discharge, erythema, erosion, ulceration, leukoplakia, scars, and masses. What is the shape of the external cervical os? A bluish discoloration of the cervix may be an indication of pregnancy or a large tumor.

A normal cervix is seen in Figure 16-23. Notice that the external cervical os is round, which is characteristic of the cervix of a woman who has never had a vaginal delivery.

Pap Smear

Traditionally, the Pap smear was done by scraping cells from the cervix, applying it to a glass slide, then fixing the cells with a preservative spray and examining the smear under a microscope (Figs. 16-24 and 16-25). A newer method, the liquid-based cytologic examination, or liquid-based Pap test, can remove most of the blood, mucus, bacteria, yeast, and pus cells in a sample (which can mask the cervical cells) and can spread the cervical cells more evenly on the slide. The cervical or endocervical sample is collected by inserting a broom-type or Cytobrush and plastic spatula into the endocervix, then rotating 360 degrees while cells are scraped from the exo- and endocervix. Instead of being directly placed on a slide, the sample is placed into a vial with a special preservative solution. This new method, performed with the ThinPrep or SurePath system, also prevents cells from drying out and becoming distorted.

Figure 16–25 Illustration of the traditional technique for obtaining a cervical smear for the Papanicolaou (Pap) test. Note that the longer end of the wooden spatula is placed in the cervical os.

Studies have revealed that liquid-based testing can slightly improve detection of cancers, greatly improve detection of precancerous conditions, and reduce the number of tests that need to be repeated. The most significant advantage of the liquid-based test is the ability to co-test for HPV with the same specimen. In 2012, several organizations and consensus groups published new guidelines for screening for cervical cancer and for management of abnormal tests. All are based on Pap and HPV co-tests as done with the liquid-based methods. In September 2012, a group or 47 experts representing 23 organizations met at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda to develop evidence-based consensus guidelines for management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests.

Because the Pap smear may cause the cervix to bleed slightly, advise the patient that she may have a little spotting, which is normal. Any significant bleeding, however, should be evaluated. The results of the Pap smear are usually available in 2 to 3 weeks.

Inspect the Vaginal Walls

The patient is told that the speculum will now be removed. The set screw is released with the examiner’s right index finger, and the speculum is rotated back to the original oblique position. As the speculum is slowly withdrawn and closed, the vaginal walls are inspected for masses, lacerations, leukoplakia, and ulcerations. The walls should be smooth and nontender. A moderate amount of colorless or white mucus is usually present. If a plastic speculum is used, carefully in a controlled fashion, unclip the two bills before removing and try to avoid pinching the sides of the vaginal wall.

Bimanual Palpation

The bimanual examination is used to palpate the uterus and adnexa. Lower the head of the examination table to a 15-degree angle or flat, depending on the patient’s preference. In this examination, the examiner’s fingers are placed in the patient’s vagina and on the abdomen, and the pelvic structures are palpated between the hands. In general, the right hand is inserted into the vagina and the left hand palpates the abdomen, but this is a matter of personal preference.

Technique

The examiner should be positioned between the patient’s legs. If the examiner’s right hand is to be used vaginally, a suitable jelly lubricant is held in the left hand, and a small amount is dropped from the tube onto the examiner’s gloved right index and middle fingers. The examiner should not touch the tube of lubricant to the gloves, because such touching will contaminate the lubricant. The patient is told that the internal examination will now begin.

As the bimanual examination is being performed, the examiner should observe the patient’s face. Her expression will quickly reveal whether the examination is painful. The labia are spread, and the examiner’s lubricated right index and middle fingers are introduced vertically into the vagina. A downward pressure toward the perineum is applied. The right fourth and fifth fingers are flexed into the palm of the hand. The right thumb is extended. The area around the clitoris should not be touched. The examiner may now rest the right elbow on his or her right knee so that undue pressure is not placed on the patient. There is no need to palpate deeply with the “abdominal hand” if the uterus is sufficiently elevated with the “vaginal hand.”

The correct positions of the examiner, assistant, and patient are demonstrated in Figure 16-26.

Figure 16–26 Positions of the examiner (right), assistant (left), and patient (bottom) for the bimanual examination.

The vaginal walls are palpated for nodules, scarring, and induration.

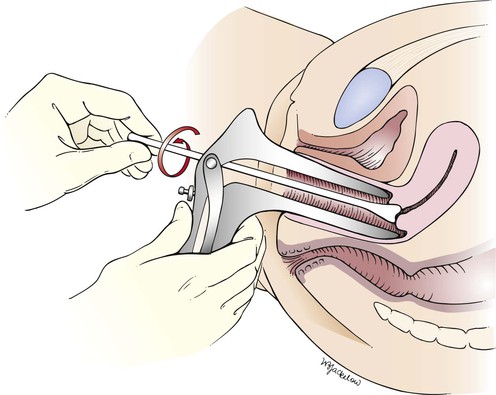

Once inserted into the vagina, the examiner’s right (vaginal) hand is rotated 90 degrees clockwise so that the palm is facing upward. Some clinicians prefer not to rotate the vaginal hand because this may decrease the depth of penetration. The left hand is now placed on the abdomen approximately one third of the way to the umbilicus from the pubic symphysis. The wrist of the abdominal hand should not be flexed or supinated. The vaginal hand pushes the pelvic organs up out of the pelvis and stabilizes them while they are palpated by the abdominal hand. It is the abdominal, not the vaginal, hand that performs the palpation. The technique for the bimanual examination is shown in Figure 16-27 and diagrammed in Figure 16-28.

Figure 16–27 Technique for the bimanual examination.

Palpate the Cervix and Uterine Body

The cervix is palpated. What is its consistency (soft, firm, nodular, friable)?

Tell the patient that she will now feel you move her cervix and uterus, but this should not be painful. The cervix can usually be moved 2 to 4 cm in any direction. The cervix is pushed backward and upward toward the abdominal hand as the abdominal hand pushes downward. Any restriction of motion or the development of pain on movement should be noted. Pushing the cervix up and back tends to tip an anteverted, anteflexed uterus forward into a position where it is more easily palpated. The uterus should then be felt between the two hands. Describe its position, size, shape, consistency, mobility, and tenderness. Determine whether the uterus is anteverted or retroverted. Is it enlarged, firm, or mobile? Are any irregularities felt? Is there any tenderness when the uterus is moved?

Palpation by the bimanual technique is easiest if the uterus is anteverted and anteflexed, which is the most common uterine position. A retroverted uterus is directed toward the spine and is therefore felt by the vaginal hand, rather than the abdominal hand in bimanual palpation.

Palpate the Adnexa

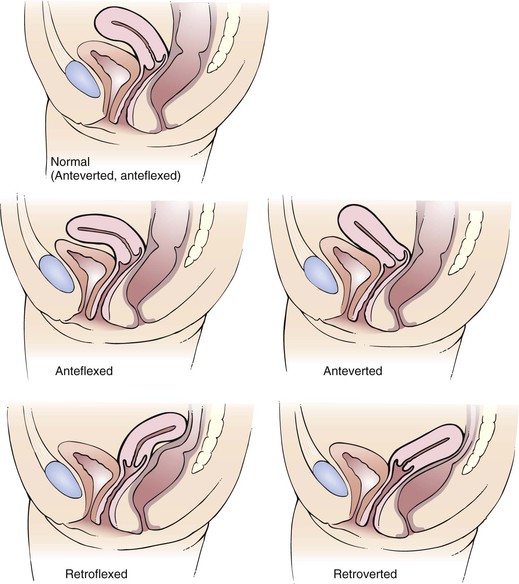

After the uterus has been evaluated, the right and left adnexa are palpated. If the patient has complained of pain on one side, start the examination on the other side. The right hand should move to the left lateral fornix while the left (abdominal) hand moves to the patient’s left lower quadrant. The vaginal fingers lift the adnexa toward the abdominal hand, which attempts to palpate the adnexal structures. This is illustrated in Figure 16-29.

Figure 16–29 Technique for palpating the left adnexa. A, Cross-sectional view through the pelvic organs. B, Position of the ovary and fallopian tube between the examining hands. C, Position of examiner’s hands.

The adnexa should be explored for masses. Describe the size, shape, consistency, and mobility, as well as any tenderness, of the structures in the adnexa. The normal ovary is sensitive to pressure when squeezed. After the left side is examined, the right adnexa are palpated by moving the right (vaginal) hand to the right lateral fornix and the left (abdominal) hand to the patient’s right lower quadrant.

In many women, especially heavier patients, the adnexal structures cannot be palpated. In thin women, the ovaries are frequently palpable. Adnexal tenderness or enlargement is relatively specific for a pathologic state.

After completion of the examination of the adnexa, the examining vaginal fingers move to the posterior fornix to palpate the uterosacral ligaments and the pouch of Douglas. Marked tenderness and nodularity are suggestive of endometriosis.

If the patient has borne children, the examiner should have no difficulty using the right index and middle fingers in the vagina for bimanual palpation. If the introitus is small, the examiner should introduce the right middle finger first and gently push downward toward the anus. By stretching the introitus, the right index finger can be introduced with little discomfort. If the patient is still tight, the examiner can ask her to contract and relax the vaginal muscles around one finger a few times before inserting the second finger. If the patient is a virgin, only the right middle finger should be used.

Rectovaginal Palpation

Palpate the Rectovaginal Septum

Tell the patient that you will now examine the vagina and rectum. The rectovaginal examination allows for better evaluation of the posterior portion of the pelvis and the cul-de-sac than does the bimanual examination alone. You can often reach 1 to 2 cm higher into the pelvis with the rectovaginal examination. Remove your fingers from the vagina, and change your glove. Explain to the patient that the examination will make her feel as if she were going to have a bowel movement but that she will not do so. Lubricate the gloved index and middle fingers. Inspect the anus for hemorrhoids, fissures, polyps, prolapse, or other growths. Insert the index finger back into the vagina while the middle finger is introduced into the anus. The examining right index finger is positioned as far up the posterior surface of the vagina as possible. This technique is shown in Figure 16-30 and diagrammed in Figure 16-31.

The rectovaginal septum is palpated. Is it thickened or tender? Are nodules or masses present? The right middle finger should feel for tenderness, masses, or irregularities in the rectum.

The patient is told that the internal examination is completed and that you are about to remove your fingers. When you withdraw your fingers, inspect them for discharge or blood. Offer the patient tissues to wipe off any excess lubricant.

Completion of the Examination

Ask the woman to move back on the examination table, remove her legs from the heel rests, and then sit up slowly. Remove your gloves and wash your hands. This concludes the examination of the female genitalia.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Vaginitis is an inflammation of the vagina and vulva that is marked by pain, itching, and vaginal discharge. Normal vaginal discharge consists of mucous secretions from the cervix and vagina, as well as exfoliated vaginal cells. A normal vaginal discharge is thin and transparent and has little odor. When the normal bacterial flora in the vagina is disturbed, one or more organisms can multiply out of their normal proportions. This change in the normal flora may also make the vagina more susceptible to other invading organisms. The rapid growth of organisms produces an excess of waste products that irritate tissues, cause a burning sensation and itching, and produce a discharge with an unpleasant odor. The discharges caused by different organisms have different appearances.

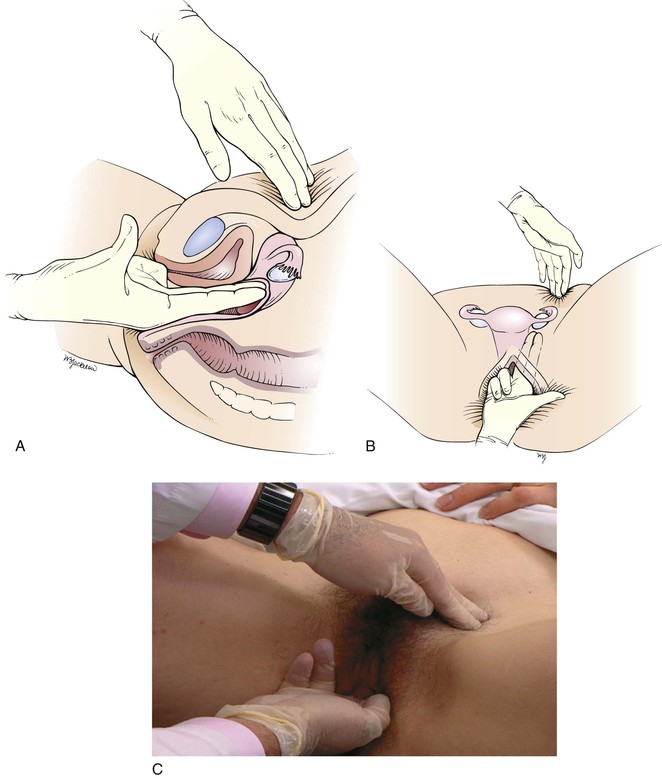

Lesions of the vulva are very common. Figure 16-32 shows the vesicular stage of herpes simplex infection. Figure 16-33 shows a chancre in a woman with primary syphilis. Chancroid is a disease in which 5 to 15 days after exposure small papules or vesicles appear that break down to form tender, nonindurated ulcers. Lymphadenopathy develops. Figure 16-34 shows the classic ulceration of vulvar chancroid. Table 16-2 summarizes the clinical features of genital ulcerations.

Figure 16–32 Herpes simplex infection.

Figure 16–33 Chancre of primary syphilis.

Figure 16–34 Chancroid.

Table 16–2

Clinical Features of Genital Ulcerations

* See Figure 16-32.

† See Figure 16-33.

‡ See Figure 16-34.

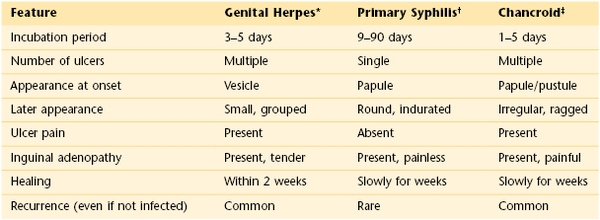

Figure 16-35 shows several of the common uterine positions.

Figure 16–35 Common uterine positions.

Pelvic relaxation is a common problem. The consequences include cystocele, rectocele, and uterine prolapse. Figure 16-36 illustrates these sequelae of relaxation of the pelvic floor.

Figure 16–36 Sequelae of pelvic floor relaxation. A, Normal anatomy. B, Cystocele, which is a protrusion of the wall of the urinary bladder through the vagina. C, Rectocele, which is a protrusion of the rectal wall through the vagina. D, Uterine descent, which is a protrusion of the uterus through the vagina.

A summary of dysfunctional uterine bleeding is illustrated in Figure 16-37.

Figure 16–37 Types of uterine bleeding. A, Normal 28-day cycle. Note that menstrual flow occurs on day 1 and lasts for approximately 5 days. B, Amenorrhea. After a menstrual flow of 5 days, the period does not recur. C, Menorrhagia. Note that the flow occurs at 28-day intervals, but the amount of flow is heavier, and its duration is longer than normal. D, Metrorrhagia. In this condition, flow is regular, but there is bleeding between the normal menstrual flow cycles.

Although the pelvic examination can reveal many cancers of the female reproductive system, including advanced uterine cancers, it is not very effective in detecting early uterine cancer. The Pap test can reveal some early endometrial cancers, but most cases are not detected by this test. In contrast, the Pap test is very effective in revealing early cancers of the cervix. As of yet, there are no recommended screening tests, either by sonogram or blood, that effectively can detect ovarian cancer.

Although there is often disagreement among various health care organizations regarding screening for various diseases, there has been a great deal of work to accomplish consensus recently regarding cervical cancer screening. In 2012, The American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, American Society for Clinical Pathology, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists essentially all agreed on the new guidelines shown in Table 16-3.

Table 16–3

Cervical Cancer Guidelines for Average-Risk Women, May 2012*

| When to start screening | Age 21 regardless of the age of onset of sexual activity |

| Annual screening | Cervical cancer screening should not be done annually. The annual visit is an opportunity to discuss other health problems and preventive measures. |

| Screening method and intervals | |

| 21–29 years of age | Cytologic examination every 3 years HPV co-test† should not be performed in women aged < 30 years |

| 30–65 years of age | Cytologic examination every 3 years or Cytologic examination + HPV co-testing every 5 years |

| When to stop screening | Aged > 65 years with adequate screening history |

| Screening posthysterectomy | Not needed unless cervix still present (supracervical hysterectomy) |

* Available at http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/pdf/guidelines.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2013.

† Co-testing using the combination of Pap cytologic examination plus HPV DNA testing is the preferred cervical cancer screening method for women 30 to 65 years old.

HPV, Human papillomavirus.

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Chlamydia screening rates too low, reinfection rates too high. [Available at] http://www.acog.org/About_ACOG/News_Room/News_Releases/2012/Chlamydia_Screening_Rates_Too_Low; March 26, 2012 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Dysmenorrhea. [Available at] http://www.acog.org/~/media/For%20Patients/faq046.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20130127T174502157 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Pelvic inflammatory disease. [Available at] http://www.acog.org/~/media/For%20Patients/faq077.pdf?dmc=1&ts=20130127T174502154 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Pelvic organ prolapse. [Available at] http://www.acog.org/For_Patients/Patient_Education_Videos/Pelvic_Organ_Prolapse [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Arbyn M, et al. Liquid compared with conventional cervical cytology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:167.

Barnhart KT. Ectopic pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:379.

Brown JS, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of a simple text to distinguish between urge and stress urinary incontinence. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:715.

Carnes M, Mahoney JE. Update in women’s health. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:538.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers. [Updated January 8, 2013. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/hpv/ [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. [Updated December 19, 2012. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Male latex condoms and sexually transmitted diseases. Condoms and STDs: fact sheet for public health personnel. [Updated December 4, 2012. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/latex.htm [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance 2011. [Updated January 23, 2013. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/default.htm [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in sexuality transmitted diseases in the United States: 2009 national data for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis. [Updated November 22, 2010. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/trends.htm [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus. [Updated March 23, 2012. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/hpv/ [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines. [Updated January 24, 2013. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/Vaccines/HPV/Index.html [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Teen pregnancy. [September 10, 2010. Updated November 21, 2012. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/TeenPregnancy/ [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unintended pregnancy prevention: contraception. [Updated April 4, 2012. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/UnintendedPregnancy/ [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010: oral cephalosporins no longer a recommended treatment for gonococcal infections. [Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6131a3.htm?s_cid=mm6131a3_w; August 10, 2012 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine information statement (interim) human papillomavirus (HPV) Gardasil. [Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/hpv-gardasil.html; February 22, 2012 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cervical cancer screening guidelines. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/pdf/guidelines.pdf [Updated March 8, 2013] .

Clarke-Pearson DL. Screening for ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;316:170.

Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1953.

Denton KJ. Liquid based cytology in cervical cancer screening. BMJ. 2007;335:1.

Drife J. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 2001.

Dwyer PL. Differentiating stress incontinence from urge urinary incontinence. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2004;86(Suppl 1):S17.

Edelman A, et al. Pelvic examination. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:e26.

Ehrmann DA. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1223.

Eifel PJ, Berek JS, Markman M. Cancer of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. ed 7. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia; 2005.

French L. Dysmenorrhea. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:285.

Garland SM, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent ano-genital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1928.

Guidace LC. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2389.

Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. 2007;370(9605):2127.

Hacker NF, Moore JG. Essentials of obstetrics and gynecology. ed 5. WB Saunders: Philadelphia; 2009.

Hathaway JK, Pathak PK, Maney R. Is liquid-based Pap testing affected by water-based lubricant? Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:66.

Hebernick D, et al. Sexual activity in the United States: results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14-94. J Sex Medicine. 2010;7(Suppl 5):255.

Holroyd-Leduc JM, et al. What type of urinary incontinence does this woman have? JAMA. 2008;299:1446.

Huh WK. Human papillomavirus infection: a concise review of natural history. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:139.

Jemel A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:8.

Kruzka PS, Kruzka SJ. Evaluation of acute pelvic pain in women. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:141.

Magee J. The pelvic examination: a view from the other end of the table. Ann Intern Med. 1975;83:563.

Meyers DS, Halvorson H, Luckhaupt S. Screening for chlamydial infection: an evidence update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:135.

National Cancer Institute. Genetics of breast and ovarian cancer. [Health Professional Version. Updated December 21, 2012. Available at] http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/genetics/breast-and-ovarian/HealthProfessional [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Nelson HD. Menopause. Lancet. 2008;371(9614):760.

Nygaard I, Barber MD. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. JAMA. 2008;300:1311.

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Current evaluation of amenorrhea. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:266.

Qaseem A, et al. Clinical guidelines: screening for HIV in health care settings: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians and HIV Medicine Association. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:125.

Ries LAG, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2004 (based on November 2006 Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results [SEER] data submission). [Bethesda, MD, National Cancer Institute. Available at] http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2004/ [Accessed June 9, 2008] .

Rollins G. Developments in cervical and ovarian cancer screening: Implications for current practice. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:1021.

Ronco G, et al. Accuracy of liquid based versus conventional cytology: Overall results of new technologies for cervical cancer screening randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335:28.

Saslow D, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine use to prevent cervical cancer and its precursors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:7.

Sawaya GF, Sox HC. Trials that matter: Liquid-based cervical cytology: Disadvantages seem to outweigh advantages. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:668.

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. American Cancer Society guidelines for the early detection of cancer, 2004. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:41.

Steinbrook R. The potential of human papilloma virus vaccines: perspective. N Engl J Med. 2007;354:1109.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Cervical Cancer. [Updated June 2012. Available at] http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscerv.htm; April 2012 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for chlamydial infection. [Available at] http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf07/chlamydia/chlamydiars.htm#clinical; June 2007 [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Weislander CK. Clinical approach and office evaluation of the patient with pelvic floor dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36:445.

Weitlauf JC, et al. Sexual violence, post-traumatic stress disorder, and the pelvic examination: how do beliefs about the safety, necessity, and utility of the examination influence patient experiences? J Women’s Health. 2010;19:1271.

Welch B, Howard A, Cook K. Vaginal itch. Australian Fam Physician. 2004;33:505.

Wilson JF. In the clinic: vaginitis and cervicitis. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151.

Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guideline, 2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Rev. 2010;59(RR12):1 http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5912a1.htm.

1 The author thanks Ellen Landsberger, MD, Associate Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Women’s Health at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY, who reviewed the chapter for this edition.

2 Named for George N. Papanicolaou, the physician who developed this screening technique. When properly performed, the Pap test can accurately diagnose cervical carcinoma in 98% of cases.

3 Not accompanied by the release of an ovum from the ovaries.

4 Endometriosis is the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus and is a cause of chronic pelvic pain.

5 High levels of glucose in the urine, as in diabetes.