Fecal Incontinence and Constipation

Most patients who require repair of an ARM suffer from some degree of a functional defecation disorder. All have some degree of an abnormality in their fecal continence mechanisms. One-quarter of them are deficient enough to the point that they are fecally incontinent and cannot have a voluntary bowel movement.1 The majority are capable of having voluntary bowel movements but may require treatment of an underlying dysmotility disorder, which most often manifests as constipation.2,3 A small, yet significant, number of patients with Hirschsprung disease suffer from fecal incontinence because of a lost anal canal or damaged sphincters that occurred during operative repair.4–6 To varying degrees, patients with spinal problems7,8 or injuries9 can lack the capacity for voluntary bowel movements.

Patients with true fecal incontinence require artificial means to be kept clean. This regimen is termed bowel management and involves a daily enema.10 On the other hand, patients with pseudoincontinence require proper medical treatment for either constipation or loose stools. This involves finding the right consistency for the stool so that they can have a bowel movement that they voluntarily control. Understanding this major differentiation is the key to deciding the correct bowel management program.

Mechanism of Continence

Fecal continence depends on three factors: voluntary sphincter muscles, anal canal sensation, and colonic motility.2

Anal Canal Sensation

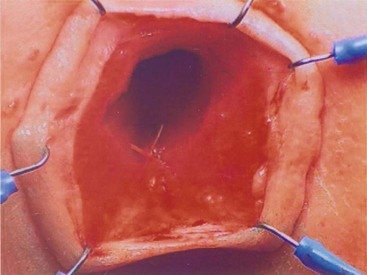

Exquisite sensation in normal individuals resides in the anal canal. Except for patients with rectal atresia, most patients with ARMs are born without an anal canal. Therefore, sensation does not exist or is rudimentary. Patients with spinal conditions may lack this anal canal sensation as well.7,8 Those with Hirschsprung disease are born with a normal anal canal, but this can be injured if not meticulously preserved at the time of their pull-through (Fig. 36-1).5,6 Also, perineal trauma may result in an injured or destroyed anal canal.9

FIGURE 36-1 Loss of the anal canal (with no visible dentate line) is seen after a Soave pull-through operation. In this patient, the anal dissection was begun too distally.

It seems that most individuals can perceive distention of the rectum. This point is important for patients undergoing pull-through procedures for imperforate anus as the distal rectum and anus must be placed precisely within the sphincter mechanism. This sensation seems to be a consequence of stretching of the voluntary muscles (proprioception). The most important clinical implication of this point is that patients might not feel liquid or soft fecal material because such stool consistency does not distend the rectum. Thus, to achieve some degree of sensation and bowel control, the patient must have the capacity to form solid stool. This is especially important in a patient without a good anal canal to give sensory cues. This point is relevant in children with ulcerative colitis who have undergone an ileoanal pull-through procedure. They can suffer from varying degrees of incontinence due to their incapacity to form solid stool, but their normal sphincter muscles and anal canal allow them to overcome this problem. Most need treatments that bulk up the stool.

Bowel Motility

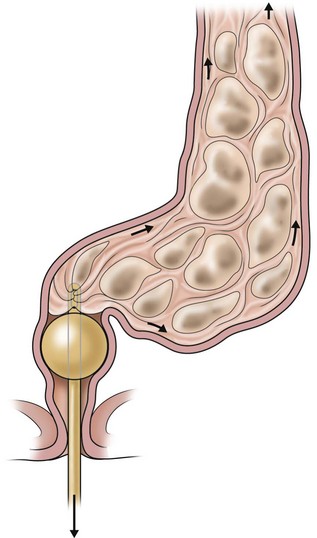

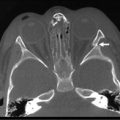

Most patients with an ARM suffer from some disturbance of this sophisticated bowel motility mechanism. Patients who have undergone a posterior sagittal anorectoplasty (PSARP) or any perineal approach in which the most distal part of the bowel was preserved can develop an overefficient bowel reservoir (megarectosigmoid) (Fig. 36-2). The main clinical manifestation is constipation, which seems to be more severe in patients with lower defects.3 Constipation that is not aggressively treated, combined with an ectatic distended colon, eventually leads to more severe constipation. A vicious cycle ensues, with worsening constipation leading to more rectosigmoid dilation, leading to more severe constipation, and then to overflow incontinence.

FIGURE 36-2 This contrast enema shows a megarectosigmoid colon. (From Peña A, Levitt M. Colonic inertia disorders in pediatrics. Curr Prob Surg 2002;39:681.)

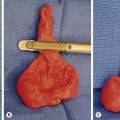

Patients with an ARM, who are managed with operations in which the most distal part of the bowel was resected (Fig. 36-3), behave clinically as individuals without a rectal reservoir. Depending on the amount of colon removed, the patient may have loose stools. In these cases, medical management consists of enemas, a constipating diet, and medications to slow down the colonic motility. Patients with Hirschsprung disease undergo operative resection of the distal aganglionic colon and rectum. However, their normal anal canal and sphincter mechanism (if properly preserved) allows the vast majority of them to be continent despite the lack of a rectal reservoir. Some patients with Hirschsprung disease have bowel hypermotility and need medications to slow the colon. Amazingly, some patients with an injured anal canal can be continent if their motility is normal because the regular contraction of the rectosigmoid can translate into a successful voluntary bowel movement.

FIGURE 36-3 This contrast enema was performed in a patient who had resection of the rectosigmoid colon. Often these patients act like they do not have a rectal reservoir. (From Levitt MA, Peña A. Treatment of chronic constipation and resection of the inert rectosigmoid. In: Anorectal Malformations in Children. Heidelberg: Springer; 2006. p. 417.)

True Fecal Incontinence

True fecal incontinence means the patient cannot have voluntary bowel movements and therefore requires an artificial mechanism to empty the colon. We have found that the ideal approach is a bowel management program consisting of teaching the patient and the parents how to clean the colon once daily with an enema so they stay completely clean for 24 hours until the next enema. This is achieved by keeping the colon quiet between enemas. Laxatives will make such a patient soil more. The program, although simplistic, is ideally implemented by trial and error over a period of one week.10 The patient is seen each day and an abdominal radiograph is obtained to look for the amount and location of any stool left in the colon. The presence or absence of stool in the underwear is also noted. The decision as to whether the type and/or quality of the enemas should be modified, as well as any changes in diet and/or medication, is made each day (Fig. 36-4).10

FIGURE 36-4 (A,B) This series of abdominal radiographs was obtained during inpatient bowel management showing progression toward a completely clean colon with daily adjustment of the enema. (C) After five days, a postcontrast abdominal film shows minimal evidence of retained fecal material.

Which Children Have True Fecal Incontinence?

In children with ARMs, 75% who have undergone a correct and successful operation have voluntary bowel movements after the age of 3 years.1 About half of these patients occasionally soil their underwear. These episodes of soiling are usually related to constipation. When the constipation is treated properly, the soiling frequently disappears. Thus, approximately 40% overall have voluntary bowel movements and no soiling, and behave normally. Children with good bowel control still may suffer from temporary episodes of fecal incontinence, especially when they experience diarrhea.

Some 25% of all patients with ARMs suffer from true fecal incontinence, and are the patients who need bowel management to be kept clean. As previously noted, certain patients with Hirschsprung disease and those with spinal problems can suffer from true fecal incontinence as well. For these patients, similar principles of bowel management learned from treatment of patients with ARMs can be applied.10

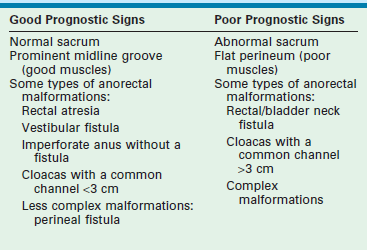

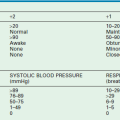

For children with ARMs, the surgeon should be able to predict in advance which patient will likely have a good functional prognosis and which child will have a poor prognosis. Table 36-1 shows the most common indicators for a good or poor prognosis. After primary repair and colostomy closure, it is possible to establish a functional prognosis (Table 36-2). Parents should be given the information regarding their child’s realistic chances for bowel control to avoid needless frustration at the age of toilet training.

TABLE 36-1

Prognostic Signs in Patients with Anorectal Malformations

| Good Prognosis Signs | Poor Prognosis Signs |

| Good bowel movement patterns: one to two bowel movements per day, no soiling in between | Constant soiling and passing of stool |

| Evidence of sensation with passing stool (pushing, making faces) | No sensation (no pushing) |

| Urinary control | Urinary incontinence, dribbling of urine |

Once the diagnosis of the specific anorectal defect is established, the functional prognosis can be predicted. If the child’s defect is associated with a good prognosis such as a vestibular fistula, perineal fistula, rectal atresia, rectourethral bulbar fistula, or imperforate anus with no fistula, one should expect that the child will have voluntary bowel movements by the age of 3 years provided the sacrum and spine are normal. These children will need careful attention to avoid fecal impaction, constipation, and soiling.3

In patients who have undergone repair of an imperforate anus and who have fecal incontinence, reoperation to relocate a misplaced rectum or repair a rectal prolapse should be considered if the child was born with a good sacrum, a good sphincter mechanism, and a malformation with good functional prognosis. A repeat PSARP can be performed and the rectum relocated within the sphincter mechanism.11

Children with an ARM who have reached the age for a bowel management program can be divided into two well-defined groups that require individualized treatment plans. The first and larger group has fecal incontinence and a tendency toward constipation. The second group has fecal incontinence with a tendency toward loose stools. Patients with fecal incontinence after operations for Hirschsprung disease and those with spinal disorders usually have a tendency toward constipation. A small group of Hirschsprung patients fall into the hypermotile group. These patients have multiple daily stools and a nondilated colon seen on a contrast enema (Fig. 36-5; see also Fig. 36-3). Interestingly, because of abnormal innervation of the colon, patients with spinal diseases can have severe constipation, yet have a nondilated colon.

Children with True Fecal Incontinence and Constipation (Colonic Hypomotility)

Patients with true fecal incontinence and a tendency toward constipation should not be treated with laxatives, but instead need an enema program. In these children, the motility of the colon is slow. The basis of their bowel management program is to clean the colon once a day with an enema. No special diet or medications are necessary. The fact that they suffer from constipation (hypomotility) is useful because it helps them to remain clean between enemas. The real challenge is to find the appropriate enema capable of evacuating the colon. Definitive evidence that the rectosigmoid colon is empty after an enema requires a plain abdominal radiograph (see Fig. 36-4). Soiling episodes or ‘accidents’ occur when there is incomplete colonic evacuation with progressive enlargement of the stool followed by leakage around the stool.

Children with True Fecal Incontinence and Loose Stools (Colonic Hypermotility)

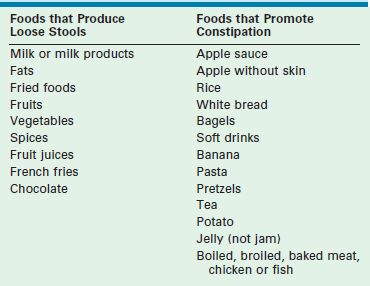

The great majority of children with ARMs who suffer from this problem were repaired before the introduction of the PSARP technique. The older procedures frequently included a rectosigmoid resection.12,13 Therefore, these children have an overactive colon because they lack a rectal reservoir (see Fig. 36-3). Rapid transit of stool results in frequent episodes of diarrhea. This means that even when an enema cleans their colon rather easily, stool keeps passing fairly quickly from the cecum to the descending colon and out the anus. To manage this situation, a constipating diet and/or medications (loperamide and water-soluble fiber) to slow down the colon are necessary. Also, eliminating foods that loosen bowel movements will help the colon slow down (Table 36-3). A small subset of patients with Hirschsprung disease (see Fig. 36-5) behaves like they have hypermotility and can be managed similarly.

The keys to the success of a bowel management program are dedication and sensitivity from the medical team. The basis of the program is to clean the colon and keep it quiet, thus keeping the patient clean for the 24 hours after the enema. It is an ongoing process that needs to be responsive to the individual patient and differs for each child. It is usually successful within a week, during which time the family, patient, physician, and nurse undergo a process of trial and error, tailoring the regimen to the specific patient. More than 95% of the children who follow this program are artificially kept clean for the whole day and can have a completely normal life.10

Bowel Management: Key Steps

The first step is to perform a contrast enema with water-soluble material, never with barium. It is very important to obtain a postevacuation film. This contrast study shows the type of colon that is present: dilated-constipated (see Fig. 36-2) or nondilated-tendency toward loose stool (see Figs 36-3 and 36-5). The enema volume and type can also be estimated from this contrast study.

The bowel management program is then implemented according to the patient’s type of colon, and the results are evaluated daily. Changes in the volume and content of the enema are made until the colon is successfully cleaned. For this, an abdominal radiograph that is obtained every day is invaluable in determining whether the colon is empty (see Fig. 36-4).

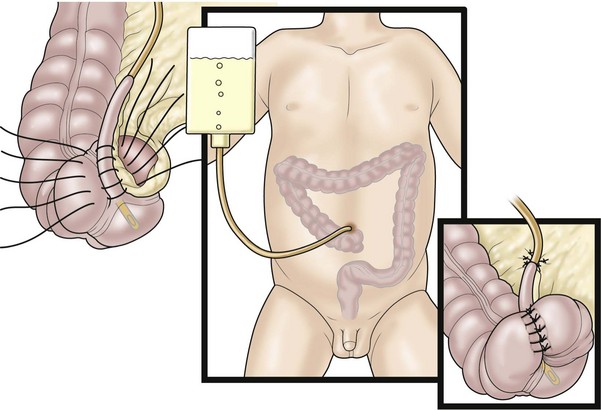

The daily enema should result in a bowel movement within 30 to 45 minutes, followed by a period of 24 hours of complete cleanliness. If the chosen enema does not radiographically clean the colon, or if the child keeps soiling, then a more voluminous or concentrated enema is needed. Administering the enema through a catheter with a balloon helps prevent leakage (Fig. 36-6). The right enema is the one that can empty the child’s colon and allow him or her to stay clean for the following 24 hours. This can be only determined by trial and error.

Children with loose stools have an overactive colon, and usually do not have a rectal reservoir. This means that even when an enema cleans their colon easily, new stool passes quickly from the cecum to the descending colon and anus. To prevent this, a constipating diet, bulking agents, and/or medications to slow down the colon can be used. Eliminating foods that loosen bowel movements will help decrease the colonic motility (see Table 36-3).

Such patients should be provided with a list of constipating foods and a list of laxative foods to avoid. The constipating diet is rigid: banana, apple, baked bread, white pasta with no sauce, boiled meat, etc. Fried foods, dairy products and sugary drinks should be avoided (see Table 36-3). Most parents learn which meals provoke loose stools and which constipate their child. To determine the right combination, treatment is initiated with enemas, a very strict diet, loperamide, and a water-soluble fiber such as pectin. Most children respond to this aggressive management within one to two weeks. The child should remain on a strict diet until clean for 24 hours for two to three days in a row. Then they can choose one new food every two to three days and the effect of this new food on the child’s colonic activity is observed. If the child soils after eating a newly introduced food, that food must be eliminated from the diet. Over several months, the most liberal diet possible should be sought. If the child remains clean with a liberal diet, the dose of loperamide can gradually be reduced to the lowest effective dose that keeps the child clean for 24 hours.

In children in whom a successful bowel management program has been implemented, the parents frequently ask if this program will be needed for life. The answer is yes for those patients born with no potential for bowel control. However, because there is a spectrum of defects, there are patients with some degree of bowel control. These patients participate in the bowel management program to avoid embarrassing accidents of uncontrolled bowel movements. As time goes by, the child becomes more cooperative and more interested in his or her problem. It is conceivable that later in life, a child may be able to stop using enemas and remain clean by following a specific regimen of a disciplined diet with regular meals (three meals per day and no snacks) to stimulate bowel movements at a predictable time. Every summer, children with some potential for bowel control can try to find out how well they can control their bowel movements without the help of enemas. Such trials are attempted during vacations to avoid accidents at school or during a time that they can stay home and try some of the toilet training strategies. It is also facilitated by daily abdominal films to ensure they are adequately emptying (see Fig. 36-4).

A key question for patients with a colostomy, who are predicted to have minimal or no potential for bowel control, is whether to perform a pull-through operation or leave them with a permanent stoma. We believe that if the patient has the capacity to form solid stool, a pull-through procedure should be performed and a daily enema given thereafter to keep them clean. A successful bowel management program will then provide a better quality of life compared with a permanent stoma. The bowel management can be initiated with a daily enema via the stoma (Fig. 36-7). If the stoma remains quiet for 24 hours between enemas, then that stoma could be pulled through or closed, and a daily enema using the antegrade Malone technique utilized.

FIGURE 36-7 Some patients have the capacity to have good bowel control with a daily enema administered through their colostomy.

Most preschool and school-age children enjoy a good quality of life while undergoing the bowel management program. However, when they are older, many express dissatisfaction. They believe that their parents are intruding on their privacy by giving them enemas. It is feasible, but rather difficult, for them to administer the enema themselves. For this specific group of children, a continent appendicostomy or Malone procedure is ideal (Fig. 36-8).14,15 Using the appendix, a valve mechanism is created and connected to the umbilicus. The appendicostomy can be catheterized to administer the enema fluid. If the child has had the appendix removed, it is possible to create a new one from a colonic flap: a continent neo-appendicostomy. The Malone procedure is just another way to administer an enema. Therefore, before performing it, the child should be completely clean through a bowel management regimen.

Consipation

Constipation in children with ARMs is extremely common, particularly in the more benign types.1,3 It is also common in patients after successful surgery for Hirschsprung disease and occurs in a large group of patients considered to have idiopathic constipation.2 When left untreated, constipation can be extremely incapacitating.3 Although diet affects colonic motility, its therapeutic value is negligible in the most serious forms of constipation. While it is true that many patients with severe constipation suffer from psychological disorders, a psychological origin for the constipation cannot explain the severe forms, because it is not easy to voluntarily retain stool when an autonomous rectosigmoid undergoes peristalsis. Passage of large, hard pieces of stool may provoke pain and make the patient behave like a stool retainer. This may complicate the problem of constipation, but it is not the original cause.

When children with ARMs and Hirschsprung disease are managed early with aggressive treatment of constipation, children with a good prognosis should toilet train without difficulty. When constipation is not managed properly, they behave much like children with idiopathic constipation and may have overflow pseudoincontinence.3 Because of a hypomotility disorder that interferes with complete emptying of the rectosigmoid, most of these patients suffer from different degrees of dilation of the rectum and sigmoid, a condition known as megarectosigmoid (see Fig. 36-2).2 Often, these children were born with a good prognosis type of anorectal defect and underwent a technically correct operation, but did not receive appropriate treatment for constipation. Subsequently they developed fecal impaction and overflow pseudoincontinence. These may also be children with severe idiopathic constipation without a prior operation, who have a dilated rectosigmoid because of years of constipation.

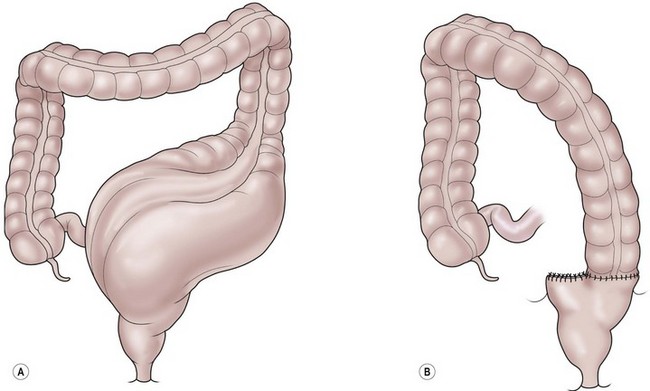

If medical treatment proves to be difficult because the child has a severe megasigmoid and requires an enormous amount of laxatives to empty, the surgeon can offer a segmental resection of the colon (Fig. 36-9). After the resection, the amount of laxatives required to treat these children can be significantly reduced or even eliminated. Before performing this operation, however, it is mandatory to confirm that the child is definitely suffering from overflow pseudoincontinence rather than true fecal incontinence with constipation. Failure to make this distinction may lead to an operation in which a fecally incontinent, constipated child is changed to one with a tendency to have loose stool, which will make the patient’s condition much more difficult to manage.

FIGURE 36-9 Resection of a dilated sigmoid colon, which can be very effective in select patients with an anorectal malformation and severe constipation.

Some clinicians treat these patients with colostomies or colonic washouts via a catheterized stoma or button device, and monitor the improvement of colonic dilatation with contrast studies.16 Once the distal colon regains a normal caliber, the physician assumes that the patient is cured and discontinues the washouts or closes the colostomy. Unfortunately, these patients’ symptoms quickly recur. We have found that washouts are often ineffective in such patients because they simply retain the fluid and believe they are really only for patients with true fecal incontinence who are incapable of having voluntary bowel movements. On the other hand, a patient with pseudoincontinence is capable of emptying their colon with the help of adequate doses of laxatives and thus does not need washouts at all.

A contrast enema with water-soluble material is an extremely valuable study. In the constipated patient, it usually shows a megarectosigmoid with dilation of the colon all the way down to the anus (see Fig. 36-2). There is usually a dramatic size discrepancy between a normal transverse and descending colon and the dilated megarectosigmoid which is the exact opposite of Hirschsprung disease. The size of the colon guides the dosing of the laxatives. It seems that the more localized the dilatation of the rectosigmoid, the better the results of a colonic resection in reducing or eliminating the laxative requirement.

Colonic manometry is sometimes useful in the evaluation of these patients. Manometry is performed by placing balloons at different levels in the colon and recording the waves of contraction or the electrical activity.17,18 Scintigraphy has also been used to assess colonic motility,19 but unfortunately does not yet help guide therapeutic decisions. The key information the surgeon needs to know is if and where a colonic resection would prove beneficial to the patient who requires enormous doses of laxatives to empty the colon.

Treatment

Determining the Laxative Requirement

It is important to remember that constipation covers a wide spectrum and patients may have laxative requirements that are much larger than the manufacturer’s recommendation. Occasionally, in the process of increasing the amount of laxatives, patients vomit, or feel nauseated and complain of abdominal cramping before reaching any positive effect. In these patients, a different medication can be tried. Some patients vomit all kinds of laxatives and are unable to tolerate the amount of laxative that produces a bowel movement that empties the colon. Others empty but have significant symptoms from the laxatives. Such a patient is considered to have an intractable condition and is a candidate for an operation. Usually, however, the dosage that the patient needs to radiographically empty the colon can be achieved. At that dose, the patient stops soiling because he or she is successfully emptying the colon each day. Because the colon is empty, the patient remains clean until the next voluntary bowel movement.

At this point, the patient and parents have the opportunity to evaluate the quality of life that they have with this treatment, understanding that this treatment will most likely be life-long. For many of these patients, a sigmoid or rectosigmoid resection can provide symptomatic improvement leading to significant reduction or complete elimination of laxatives.20

Rectosigmoid Resection

The megarectosigmoid is resected and the descending colon is anastomosed to the rectum (see Fig. 36-9).21 This can be done laparoscopically and ideally only leaves a small rectal cuff. These patients must be followed closely because the condition is not cured by the operation. The remaining rectum is most likely abnormal. Without careful follow-up and treatment of constipation, the colon can re-dilate.

In patients with ARMs, it is particularly vital to keep the rectum intact because they need it for continence. It is their reservoir in which they feel the distention of the stool. In contrast, patients with idiopathic constipation who have not undergone an operation and have a normal anal canal and sphincters, the rectum and sigmoid can be resected with preservation of fecal continence. This is only done in the rare case that the rectum is significantly dilated. Resection of the rectosigmoid down to the pectinate line can be performed in a similar manner as used for patients with Hirschsprung disease with anastomosis of the nondilated colon to the rectum above the pectinate line.22 It seems that a laparoscopic low anterior resection is best to avoid over-stretching the sphincters, leaving behind a small cuff of rectum. Dramatic improvement in the patient’s ability to empty the colon has resulted.

References

1. Peña, A. Anorectal malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg. 1995; 4:35–47.

2. Peña, A, Levitt, MA. Colonic inertia disorders. Curr Prob Surg. 2002; 39:666–730.

3. Levitt, MA, Kant, A, Peña, A. The morbidity of constipation in patients with anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2010; 45:1228–1233.

4. Bax, KMA. Duhamel Lecture: The incurability of Hirschsprung’s disease. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2006; 16:380–384.

5. Levitt, MA, Martin, C, Olesevich, M, et al. Hirschsprung’s disease and fecal incontinence: Diagnostic and management strategies. J Pediatr Surg. 2009; 44:271–277.

6. Levitt, MA, Dickie, B, Peña, A. Evaluation and treatment of the patient with Hirschsprung disease who is not doing well after a pull-through procedure. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010; 19:146–153.

7. Smith, GK. The history of spina bifida, hydrocephalus, paraplegia, and incontinence. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001; 17:424–432.

8. Eire, PF, Cives, RV, Gago, MC. Faecal incontinence in children with spina bifida: The best conservative treatment. Spinal Cord. 1998; 36:774–776.

9. Hayden, DM, Weiss, EG. Fecal incontinence: Etiology, evaluation, and treatment. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011; 24:64–70.

10. Bischoff, A, Levitt, MA, Peña, A. Bowel management for the treatment of pediatric fecal incontinence. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009; 25:1027–1042.

11. Levitt, MA, Peña, A. Reoperations in Anorectal Malformations. In: Teich S, Caniano D, eds. Reoperative Pediatric Surgery. Totowa: Humana Press; 2008:311–326.

12. Kiesewetter, WB. Imperforate anus II: The rationale and technique of the sacro-abdomino-perineal operation. J Pediatr Surg. 1967; 2:106–110.

13. Rehbein, F. Imperforate anus: Experiences with abdomino-perineal and abdomino-sacro-perineal pull-through procedures. J Pediatr Surg. 1967; 2:99–105.

14. Rangel, SJ, Lawal, TA, Bischoff, A, et al. The appendix as a conduit for antegrade continence enemas in patients with anorectal malformations: Lessons learned from 163 cases treated over 18 years. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:1236–1242.

15. Lawal, TA, Rangel, SJ, Bischoff, A, et al. Laparoscopic assisted Malone appendicostomy in the management of fecal incontinence in children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011; 21:455–459.

16. Marshall, J, Hutson, JM, Anticich, N, et al. Antegrade continence enemas in the treatment of slow-transit constipation. J Pediatr Surg. 2001; 36:1227–1230.

17. DeLorenzo, C, Flores, AF, Reddy, SN, et al. Use of colonic manometry to differentiate causes of intractable constipation in children. J Pediatr. 1992; 120:690–695.

18. Sarna, SK, Bardakjian, BL, Waterfall, WE, et al. Human colonic electric control activity (ECA). Gastroenterology. 1980; 78:1526–1536.

19. Cook, BJ, Lim, E, Cook, D. Radionuclear transit to assess sites of delay in large bowel transit in children with chronic idiopathic constipation. J Pediatr Surg. 2005; 40:478–483.

20. Peña, A, El-Behery, M. Megasigmoid—a source of pseudo-incontinence in children with repaired anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 1993; 28:1–5.

21. Levitt, MA, Pena, A. Surgery and constipation: When, how, yes, or no? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005; 41(Suppl. 1):S58–S60.

22. Levitt, MA, Martin, CA, Falcone, RA, et al. Transanal rectosigmoid resection for severe intractable idiopathic constipation. J Pediatr Surg. 2009; 44:1285–1291.