Problem 47 Fatigue and bruising in a teenager

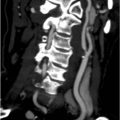

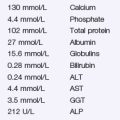

The following investigations become available.

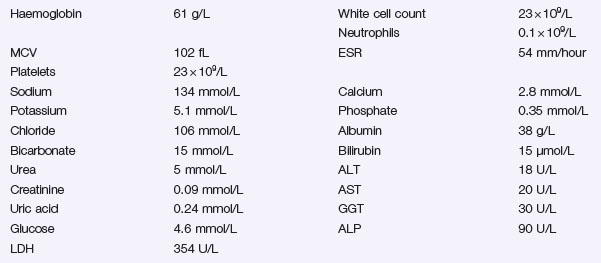

Blood film (Figure 47.1) comment:

Infectious mononucleosis screen (IM): Negative. EBV IgM: Negative.

Q.2

Interpret the blood test results. What further investigations and management should be arranged?

Q.3

What investigations should be performed immediately, and what treatment would you like to start?

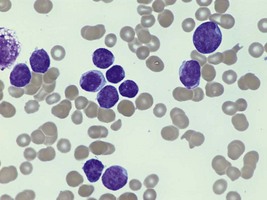

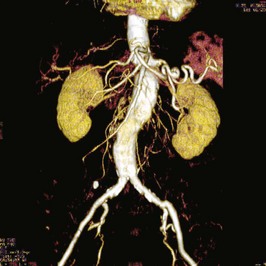

An urgent bone marrow aspirate is performed (Figure 47.2). Microscopic examination of the aspirate smears shows over 90% blasts, immature chromatin, few nucleoli, scant cytoplasm and few granules. Immunophenotyping of the bone marrow aspirate shows the presence of a lymphoblast populations staining for CD45, CD5, CD7, and cytoplasmic CD3, but negative for cell surface CD3, negative for the B lymphoid markers CD19 and CD79a, and negative for the granulocytic markers CD13 and CD33.

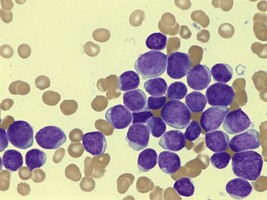

He is sitting on the edge of his bed with respiratory rate of 25, a peripheral oxygen saturation of 94% on air and mild facial swelling. Chest examination reveals dullness to percussion at the right lung field base, with reduced breath sounds on the right side. You repeat the chest X-ray (Figure 47.3).

Revision Points

Issues to Consider

Acute leukemia. In Hoffbrand A.V., Moss P.A.H., Pettit J.E., editors: Essential haematology, 5th edn, Oxford: Blackwell, 2006. ch 12. This is an excellent book covering normal and malignant disorders aimed at medical students

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia. In Pui C.H., editor: Childhood leukemias, 2nd edn, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ch 16. A detailed textbook covering all aspects of the biology and management of ALL

www www.leukaemia.org. A UK-based web resource for parents and sufferers