CHAPTER 19 Fat Repositioning in Lower Blepharoplasty

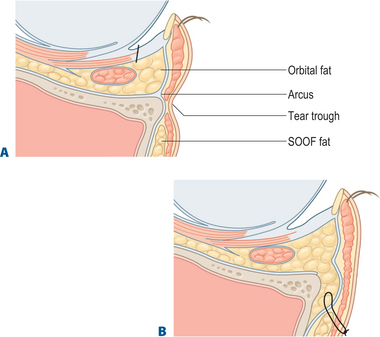

The objective of facial rejuvenative surgery is to restore a youthful contour. With age, changes occur in the lower eyelid and cheek that involve descent of the cheek tissues as well as prolapse of orbital fat in the lower eyelid. Perhaps even more importantly, deflation occurs: there is loss of volume in the subcutaneous and deep fat pads in the periorbital region. Val Lambros1 (see Chapter 2) has articulated beautifully the concept that focal loss of volume, often in areas of cutaneous attachment of the skin to deep structures, can mimic descent of the soft tissue. In the periorbital area, focal loss of volume along the orbital rim can unveil the contours of the orbital fat bound by the arcus marginalis, and of the suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF) limited by the orbitomalar ligament. This results in the formation of a tear trough groove at the level of the inferior orbital rim. Filling the areas of periorbital deflation can be a powerful rejuvenative technique. One useful option, when adequate orbital fat is available for transposition, is the transposition of fat over the orbital rim onto the superior face of the maxilla. In this chapter, I will describe the transconjunctival approach to orbital fat repositioning.

Lower eyelid fat transposition is a step in the evolution of blepharoplasty surgery. Thirty years ago, lower blepharoplasty was viewed as an operation to remove skin and fat in the lower eyelid. This often produced rounding of the lateral canthal angle, lower eyelid retraction with scleral show, and did not improve skin quality in the lower eyelid. The transconjunctival approach to fat excision was reintroduced 20 years ago, and over the last 10 years, we have been simultaneously treating skin quality with chemical peeling and ablative or non-ablative laser treatments. The newest stage of evolution of lower blepharoplasty is an understanding of the concept of fat preservation. Loss of fat in the face is an aging change. Although some young patients do have a true excess or atypically prolapsed orbital fat compartment with a substantial bulge in the lower eyelid that is treated with fat removal, many older patients who come in for rejuvenation of the lower eyelid and midface have contours that are characterized by hollows over orbital rim. This contour is related to the bony support of the underlying maxilla and is accentuated when the maxilla is relatively hypoplastic. A tear trough deformity is unveiled by deflation of the overlying tissues; it is located along the inferior orbital rim between the demarcation of the septal attachment above and the cheek fat pad and SOOF below. When deflation results in a tear trough depression or orbital rim hollow, removing orbital fat alone may accentuate the tear trough deformity. For these patients, who present with a double convexity contour of the lower eyelid and cheek, the orbital fat is better repositioned over the rim rather than excised.

Surgical technique

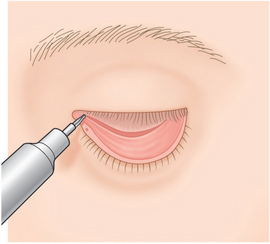

The tear trough is marked with a surgical marking pen on the skin surface before surgery begins, in order to guide the intraoperative placement of the fat pedicle. The initial portion of the surgery is identical to any other transconjunctival blepharoplasty, with a forniceal incision and wide open sky exposure of the individual fat pockets (Fig. 19-1). The lateral and central fat pockets may be debulked as determined preoperatively.

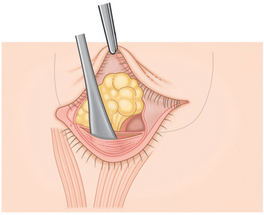

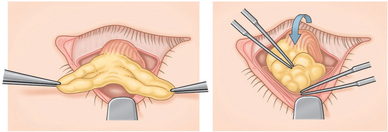

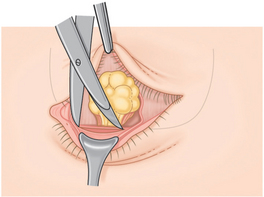

Next, the arcus marginalis is identified. The inferomedial orbital rim is palpated with the tips of a Stevens’ scissors and blunt dissection on the palpable bony orbital margin reveals the white tissue condensation representing the arcus marginalis (Fig. 19-2). Cutting cautery is useful to control bleeding from the small bony perforators that sometimes occupy this area, and to cut through the periosteum to reach the bony surface of the maxilla. Dissection is then carried out over the orbital rim by lifting the periosteum using a sharp elevator, taking care to keep the arcus marginalis and orbital septal attachment intact. The entire area of intended fat pedicle placement is undermined guided by the previously placed blue marks (Fig. 19-3). Some surgeons have suggested that the suborbicularis (supraperiosteal) plane is preferable. However, the subperiosteal plane has the advantage of being relatively blood free and straightforward. The periosteum in this area is fairly loose and the fat can be easily repositioned into the subperiosteal pocket.

Figure 19-2 The orbital rim is exposed at the level of the arcus marginalis, using blunt dissection.

Adapted from Goldberg RA: Transconjunctival orbital fat repositioning: transposition of orbital fat pedicles into a subperiosteal pocket. Plast Reconstr Surg 2000; 105(2):743–748, with permission of Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins.

Medial, central, and sometimes lateral fat pedicles are created using gentle dissection. Often, the largest fat pedicle is created from the medial fat pocket. Although there are some large vessels in the medial fat pad (and it is preferable to avoid cutting across them), the fat pedicle is essentially a random flap. The stalk of the pedicle should be large enough to provide reasonable blood supply, but small enough to avoid pulling on the orbital connective tissue system as the pedicle is transposed over the rim. We most often construct a ‘T’ shaped pedicle with a base measuring 5 to 10 mm in diameter. The central fat pocket is variable in size, occasionally larger than the medial pocket. The pedicles are transposed over the orbital rim and placed into the predissected pocket and distributed evenly within it (Fig. 19-4). Forced ductions of the globe are then checked to be sure that the fat is not attached by the pedicle to the motility system of the orbit: there should be no movement or tugging on the pedicle as the globe is rotated.

A number of different techniques are available to fixate the pedicles within their subperiosteal pocket. The pedicle can be sutured to the trailing edge of the SOOF fat using buried absorbable sutures, but exposure of the deep aspect of the pocket can be difficult. Another technique involves fastening to the tip of the fat pedicle a double armed 6-0 gut suture (or polypropylene pullout suture, without knots) in a fashion analogous to imbricating the extraocular muscles during strabismus surgery. These sutures are then externalized from the deep margin of the subperiosteal pocket out to the skin. Another method utilizes an externalized 6-0 polypropylene ‘cage’ suture to fixate the pedicle into the flap. Three or four lazy loops are passed from the lower eyelid, across the pedicle just above the bony orbital rim, and exiting on the upper cheek (Fig. 19-5). These loops form a ‘cage’ that keeps the pedicle in position during the early healing phase. The sutures are removed at three to five days.

Discussion

Periorbital hollows appear with age, and must be appropriately diagnosed and treated in order to optimally rejuvenate the lower eyelid and midface. The concept of filling the inferior orbital rim trough using alloplastic implants or fat is not new.2–9 The transconjunctival approach can be utilized to place an alloplastic implant, reposition fat, and perform a midface lift. The advantages of this approach include a decreased risk of lower eyelid retraction (since the orbital septum is not violated) and the absence of a cutaneous scar.10

In the past, the arcus marginalis release was often performed in a supraperiosteal suborbicularis plane. It was believed that this may lead to a more natural contour and perhaps a better blood supply.10 However, the supraperiosteal plane is more vascular, and bleeding from branches of the angular artery is often a problem. In contrast, the subperiosteal plane is an easier dissection plane and is essentially avascular, therefore, minimal or no bleeding is encountered. Blood supply does not seem to be a problem although in either plane, the fat pedicle probably has some degree of ischemia and variable absorption can occur. The margins of the subperiosteal pocket have a natural tapering shape due to the periosteal attachment to bone. Therefore, the subperiosteal plane provides a natural contour to the fat and may decrease the chance that the borders of the fat pedicle will create a visible demarcation.

Complications are generally similar to complications of traditional transconjunctival blepharoplasty. The most worrisome potential complication is double vision.11 The orbital motility system is complex, and subtle perturbations caused by mechanical disruption or scar tissue formation can result in restriction of ocular motility and double vision. It may not be possible to completely avoid this complication, but gentle dissection, judicious use of cautery, and careful checking of globe rotation after the pedicles are transposed, may decrease the incidence of postoperative diplopia. Lower eyelid retraction is another potential competition of fat repositioning; careful dissection at the arcus marginalis, to minimize risk of injury to the orbicularis or orbital septum, may decrease the risk of lower eyelid retraction.

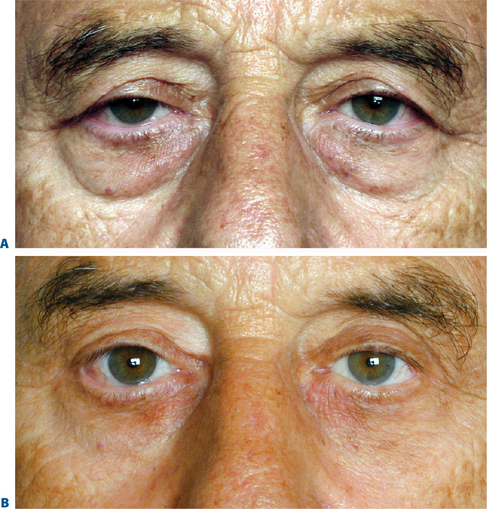

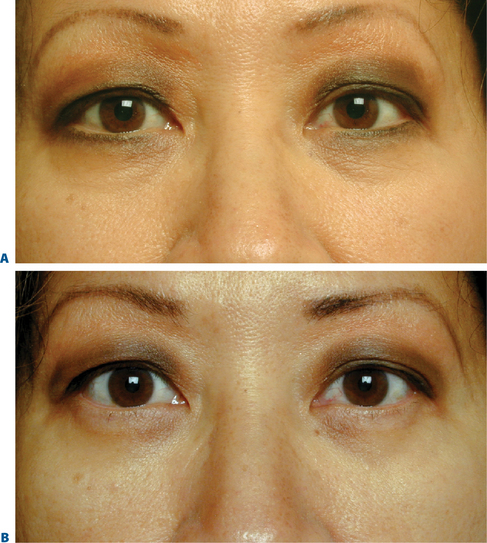

Options to fill the periorbital hollows include free autogenous grafts such as fat, synthetic injectable fillers, and orbital fat repositioning. When adequate orbital fat is available for transposition, the technique of fat repositioning provides a subtle but long lasting change in the contour of the lower eyelid. It is not as powerful as an alloplastic implant such as the Flowers tear-trough implant,2 but has the advantage of vascularized autogenous tissue. Due to the additional dissection required to create the subperiosteal pocket, there is a longer period of postoperative edema compared to the more limited dissection of standard fat removal lower blepharoplasty. In addition, some patients may experience hardening of the fat pedicle during the first three postoperative months. This may represent a combination of postsurgical fibrosis and some degree of liponecrosis and lipogranuloma formation. This usually resolves by six months. The survival and persistence of the transposed fat is variable (Figs 19-6 to 19-8), however, almost all patients experience a long-term improvement in contour.

1 Lambros VS. Discussion of ‘The midface sling: A new technique to rejuvenate the midface’ by Yousif NJ, Matloub H, Adam N, Summers AN. Plast Reconst Surg. 2002;110(6):1554-1555.

2 Flowers RS. Tear trough implants for correction of tear trough deformity. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:403-415.

3 Steinsapir KD, Shorr N. Suborbital augmentation. In: Bosniak S, editor. Principles and Practice of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996:484-503.

4 Goldberg RA, Baylis HI, Goldey SH. Transconjunctival lower blepharoplasty. In: Bosniak S, editor. Principles and Practice of Ophthalmic Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996:626-631.

5 Loeb R. Naso-jugal groove leveling with fat tissue. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20(2):393-400.

6 Loeb R. Fat pad sliding and fat grafting for leveling lid depressions. Clin Plast Surg. 1981;8:757-776.

7 Hamra ST. Arcus marginalis release and orbital fat reposition in midface rejuvenation. Plast Reconst Surg. 1995;92(2):354-362.

8 Hamra ST. The role of orbital fat preservation in facial aesthetic surgery. A new concept. Clinics Plast Surg. 1996;23(1):17-28.

9 Eder H. Importance of fat conservation in lower blepharoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1997;21:168-174.

10 Baylis HI, Long JA, Groth MJ. Transconjunctival lower eyelid blepharoplasty. Techniques and complications. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1027-1032.

11 Goldberg RA. Transconjunctival orbital fat repositioning: Transposition of orbital fat pedicles into a subperiosteal pocket. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:743-748.

12 Goldberg RA, Yuen VH. Restricted ocular movements following lower eyelid fat repositioning. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:302-305.