CHAPTER 12 Fat Injections to the Breast

The Lipomodeling Technique

Summary/Key Points

Introduction

Transferring fat from parts of the body where it is in excess to the breast for cosmetic and esthetic purposes has been a long-lasting objective, and probably also a long-lasting dream.

This approach has been considered since the very beginning of liposuction, particularly after the publication of the works of Illouz1 and Fournier.2 However, it remained controversial and was not widely used until the development of more precise tools and techniques. It was feared that autologous fat transfer would generate fat necrosis and calcifications which, at that time, were not readily assessable because of the limitations of existing imaging modalities.

The final blow came in 1987. After the presentation of a case by Bircoll,3 the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons recommended to stop using fat tissue injections for the aka Brustvergrößerung. The technique regained popularity after confirmation by Coleman4,5 that fat tissues could be transplanted safely provided that adequate care is given to the preparation and transfer of fat cells. In 1998, given the proven efficacy of fat transfer to the face for facial rejuvenation or post-surgery reconstruction, we developed a research program aimed at evaluating the efficacy of the procedure for thoracomammary reconstruction. We developed the technique named ‘lipomodeling’,6,7 then assessed its efficacy and tolerability in patients and demonstrated the absence of clinical or radiological signs of adverse effects.

The objective of the present chapter is to examine the history and illustrate the progression of knowledge about the lipomodeling technique used in our unit, to describe indications, contraindications, as well as potential complications associated with its use, and finally to provide input regarding the most effective means of preventing or resolving these problems.

History of the Technique and Progression of Ideas

First attempts

Fat grafting for breast plastic surgery has long been advocated by prominent surgeons. In 1895, at the German Congress of Surgery, Czerny described the first clinical case of breast reconstruction by transplantation of a giant lipoma of the lumbar region to the breast. Adipose cells were used to fill the void left in the breast after tumor resection in a patient with a fibroadenoma.8,9 Some surgeons thereafter performed breast reconstruction or augmentation using fascio-cutaneous flaps,10 gluteus fat implants,11 or local pedicle flaps.12 Injections of fat either directly into the breast1,2,13 or into previously inserted implants14 have also been reported. Some authors have even described the cases of women undergoing augmentation mammaplasty by cadaver fat allografts.15,16

Liposuction experiments published by Illouz1 contributed to the development of the technique and to the worldwide generalization of the concept. It became tempting to use autologous fatty tissues collected by liposuction for breast augmentation, as primarily done by Illouz. Similarly, in 1991, Fournier described the fat-grafting technique which he used only in patients who refused prostheses and who desired only moderate breast augmentation.2 The quantity of fat grafted to the patients was between 100 and 250 ml in each breast, injected in the retroglandular space, not in the mammary parenchyma.

At the time, many surgeons viewed the new procedure with skepticism. The technique had not been standardized and it was not possible to guarantee the absence of fat necrosis following fat transfer. Breast imaging techniques were not as accurate as they are today; any mammary tumefaction could cause mammographic changes and give rise to diagnostic confusion, and there was a fear that areas of fat necrosis might interfere with breast cancer detection.

The controversy

Fat grafting to the breasts has been highly controversial since the presentation by Bircoll, first in Bangkok in 1984, then at the California Society of Plastic Surgeons in 1985, of a case undergoing breast augmentation by injection of fat cells obtained by liposuction. The patient was a 20-year-old woman who requested a moderate augmentation of her breast while undergoing fat grafting to repair the damages caused by a dog bite. Bircoll3 considered the technique should only be used for women requesting moderate augmentation because of the potential risk of necrosis when grafting large quantities of fat. He reported the main advantages of the procedure: simplicity, absence of scar, early recovery, avoidance of prosthesis use and thereby of prosthesis-related complications, as well as the positive slimming impact at the site of fat removal. In April 1987,17 Bircoll reported the case of a patient undergoing bilateral fat grafting after unilateral reconstruction by transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM; improved aesthetic results and symmetry). The two papers triggered controversial reactions from the medical community18–21 who deplored that autologous fat injections in the breasts could generate microcalcifications and cysts, possibly interfering with the detection of early breast carcinoma. Bircoll argued22,23 that cancer-related calcifications and those consecutive to fat transplantation occur in different sites and have different radiological aspects, and therefore cannot be mistaken, and that breast reduction surgery also is responsible for microcalcifications, but the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons stated:

The committee is unanimous in deploring the use of autologous fat injection in breast augmentation, much of the injected fat will not survive, and the known physiological response to necrosis of this tissue is scarring and calcification. As a result, detection of early breast carcinoma through xerography and mammography will become difficult and the presence of disease may go undiscovered.

There was no explicit reference to scientific findings and the report only expressed the opinion of the members of the committee. Despite the paucity of scientific information and although it had long been recognized that any mammary surgery can be responsible for the occurrence of fatty cysts or mammographic changes, the injection of fat into the breasts became taboo among surgeons. The ASPRS banning put an end to any research or experimentation on the subject.

Ironically, in 1987, a retrospective study of the mammographic changes after breast reduction published in the same journal24 reported that calcifications were detectable in 50% of all mammograms at 2 years from surgery. The author insisted that in most cases these benign calcifications were easily distinguishable from cancer. Despite this high incidence and the risk for mammography abnormalities to interfere with cancer detection, there was no discussion of discontinuing breast reductions.

Progressive lifting of the taboo

The demonstration of the efficacy of fat transfer, based on atraumatic fat harvesting and injection, for facial rejuvenation and for the correction of facial deformities4,5 prompted us to adapt the technique to breast reconstruction. The contribution of fat grafting to the thorax and the breast for breast reconstruction has been one of our principal research topics over the past ten years. First, we used fat grafting along with autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction. This method, previously developed by our surgical unit,25–27 allowed satisfactory reconstruction in 70% of the cases. However, the other 30% resulted in insufficient breast volume and reduction of the contralateral breast was needed, or else insertion of a prosthesis; in this case, the procedure was no longer autologous and the patients suffered the drawbacks of prostheses (unnatural shape and texture, and obligation to change the prosthesis after a while). We started using fat grafting in breast cancer patients undergoing autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction who were at low risk of local recurrence. We named the technique ‘lipomodeling,’ from the Greek root lipo for fat, and the Latin word modello which means to give shape or volume, which is exactly the objective of this procedure. At first, only volunteer patients who agreed to undergo strict follow-up were operated on. Then, after the demonstration of the efficacy of the technique, we proposed it to almost all patients treated by latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction. Fat grafting provides them with optimal breast shape and texture as well as a natural cleavage. The study of mammography, computed tomography (CT)-scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings conducted in parallel28 demonstrated that the impact of lipomodeling on the patient’s images was far from negative. It was thus progressively extended to other indications of breast reconstruction, then to the correction of breast deformities, to the treatment of sequelae of conservative treatment and, more recently, to breast cosmetic surgery.

Our first presentations28,29 raised considerable controversy, similar to criticisms made in 1987. Point-by-point debate gradually won over the hostility of the clinical community and fat grafting has now become a standard procedure in breast reconstruction.7,30,31

Operative Technique6,7,31

Preparation

The patients are given information about the technique and about possible risks and complications. Each patient receives one of four information leaflets corresponding to her situation: ‘Lipomodeling in breast reconstruction,’ ‘Lipomodeling for the correction of breast conservative treatment sequelae,’ ‘Lipomodeling for the correction of breast malformations,’ and ‘Aesthetic breast lipomodeling.’

It is essential that the patient be at her ideal weight at the time of lipomodeling. Fat cells have a memory of their origin and, if the patient loses weight after the procedure, grafted cells may not survive.

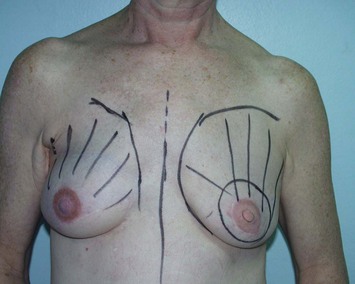

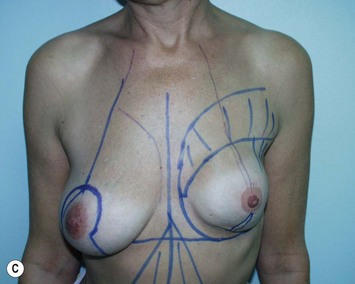

Careful clinical examination of the breast areas to be treated is required. They are identified and marked on the skin before the operation (Fig. 12.1). In addition to commonly used two-dimensional images, three-dimensional morphological images are taken and compared to evaluate the quantity of fat that should be grafted and estimate fat resorption.

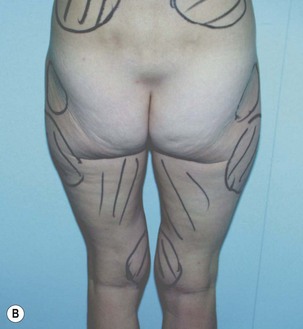

The various fatty areas in the patient’s body are examined to identify and locate natural fat deposits. Usually, the fat cells used for lipomodeling are those taken from the abdominal region. The patients are satisfied with the local thinning effect; and also, the procedure is easy for the surgeons since it is not necessary to change the patient’s position between collection and grafting. The second most frequent site for fat harvest is the trochanter (flabby thighs), and the inner side of the thighs and knees. Areas of fat harvest are visualized and marked with skin-marking pen (Fig. 12.2).

Anesthesia

Successful breast reconstruction requires sufficient quantities of fat cells and the harvesting procedure is somewhat long. This is why most patients undergoing lipomodeling are placed under general anesthesia. In breast cancer patients undergoing postmastectomy reconstruction, the procedure is associated with nipple–areola reconstruction and contralateral breast symmetry. As is generally recommended in our unit for patients undergoing plastic surgery, perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is given to all patients. No lipomodeling-specific antibiotic treatment is given.

Local anesthesia is considered only for patients requiring moderate lipomodeling, generally for secondary management of a residual scar.

Incisions

Fat is harvested by making incisions with a No. 15 blade: four periumbilical incisions are performed for collecting abdominal deposits, and two lateral incisions (one on each side) for lateroabdominal or suprailiac deposits. Fat cells in the thighs are removed through incisions in the buttock fold (one on each side), and frequently also in the inner side of the knees.

When the patient requiring lipomodeling has had previous surgery to the breast, the procedure can be performed through the same incisions. In total, five or six incisions are made to reduce the convergence of graft tunnels: at least two in the inframammary fold and one in the upper breast quadrant. To keep scars to a minimum, incisions are generally made with the beveled edge of a cutting blade.

Fat harvesting

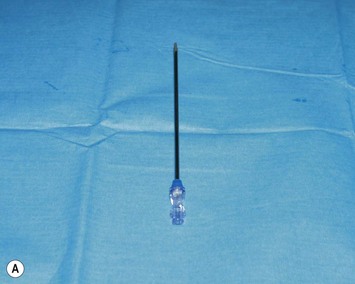

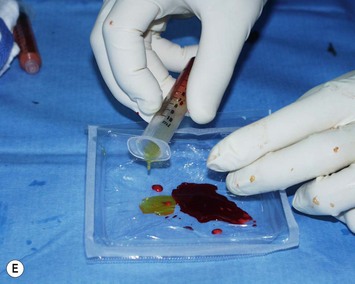

Recent work in the field has contributed to the standardization of the methods to be used for fat harvesting and grafting, and for the limitation of hazards at each step of the procedure. Only a strict observation of the rules at the different steps can ensure satisfactory median and long-term fat cell survival.4–79 Fat is harvested using a disposable cannula or a Coleman harvesting cannula. These blunt-tipped cannulas are inserted through 4 mm incisions made with a No. 15 blade, and directly attached to a 10 ml Luer-lock syringe. Fat cells are collected by moderate aspiration (Fig. 12.3) to minimize trauma on the adipocytes and improve the number of viable transplanted cells. The volume of fat aspirates must be enhanced to account for the cell loss incurred by centrifugation, refinement and transplantation.

Fig. 12.3 Fat cell collection. A Disposable harvest cannula. B Fat cell collection using a disposable harvest cannula attached to a 10 ml Luer-lock syringe.

For better cosmetic results, the areas where fat cells have been harvested are smoothed by classical liposuction with a 4 mm cannula. Skin incisions are sutured with absorbable stitches.

Conditioning of the graft

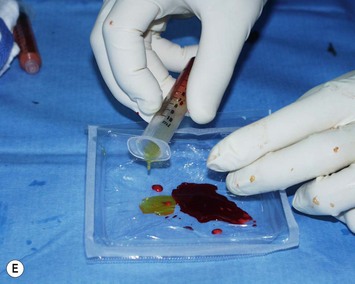

During fat harvesting, a surgical assistant prepares the cells for centrifugation by placing a screw cap on the extremity of each syringe (Fig. 12.4), then syringes are subjected to 3-minute centrifugation at 3200 rpm (Fig. 12.4). Six syringes can be processed at a time.

Fig. 12.4 Preparation of the fat cells.

A Placement of a screw cap on top of the syringe. B Centrifugation of syringes (six syringes at a time). C Centrifugation separates the graft into three layers. Only the layer containing purified fat cells is reinjected to the patient. D Elimination of the bottom layer (serum and residues) by opening the cap.E Elimination of the upper layer (oily supernatant). F Transfer from one syringe to another using a three-way tap; 10 ml of pure fat cells are collected.

During centrifugation, harvested fat cells are separated into three layers (Fig. 12.4C):

Careful planning is necessary to ensure efficient and rapid preparation of the fat graft. Fat cells are transferred from one syringe to the other using a three-way stopcock, then collected into 10 ml fractions (Fig. 12.4F).

Placement of the fat graft

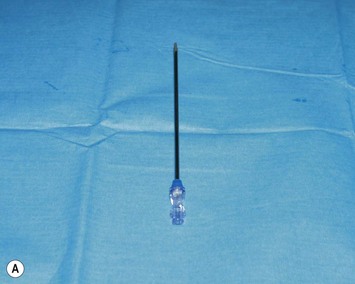

When all fat samples have been processed, a number of 10 ml syringes of purified fat aspirates are available. The fat is then transferred directly from the 10 ml syringes to the breast area by adapting specific disposable cannulas of 2 mm diameter. These cannulas (Fig. 12.5A) are slightly longer and more resistant than those used for fat grafting to the face because higher mechanical constraints are associated with injection of fat into more solid and more fibrous tissues.

Fig. 12.5 Placement of the fat graft.

A Disposable transplantation cannula specific for lipomodeling. B Breast incision with a 17G needle knife. C Modalities of fat transfer: injection of small, spaghetti-like strips of fat while pulling the cannula back. D Fat transfer to the breast.

Incisions to the breast are performed using a 17 gauge needle knife (Fig. 12.5B). These small incisions allow for the passage of the cannula while limiting the impact of scarring and preserving the cosmetic results of the procedure which becomes almost invisible with time. Multiple small incisions, positioned to allow accurate placement of graft tunnels in different radial directions are required to ensure correct shaping.

It is recommended to inject the fat in small spaghetti strips (Fig. 12.5C), in multiple layers and multiple directions, from deep to superficial tissues (Fig. 12.5D), following a three-dimensional grid pattern. A good spatial representation of the area is required to avoid injecting large fat clumps potentially responsible for fat cell necrosis. On the contrary, each aliquot must be injected in a well-vascularized area, at a distance from other injection sites, and under low pressure (while gently pulling the cannula back).

The volume of fat transferred to the patient must be overestimated (whenever possible) to account for 30% fat resorption after injection. As a rule, one must graft at least 140 ml of fat cells to obtain a final volume of 100 ml.

When receptor tissues are so saturated that they can no longer absorb fat cells, injections should be discontinued in order to avoid the formation of fat deposits prone to steatonecrosis (monitoring of tissue saturation). Replication of lipomodeling after several months is easier and is recommended for better results. Skin incisions in the breast are sutured with extra-fine absorbable stitches, then covered with dry bandage for a few days.

Postoperative Care

At the donor site

As for liposuction, patients complain of acute pain generally amenable to standard pain medications until 48 hours after the procedure. Diluted ropivacaine is infiltrated at the end of the cell harvest to minimize pain during the first 24 hours after the procedure. The patient may feel some discomfort during the following 2 or 3 months. At the end of the fat harvest, a compression dressing is applied to the site of wound, secured with Elastoplast and left in place for 5 days. Class-A analgesic medication is given for 2 weeks.

The procedure causes bruising that resolves after approximately 3 weeks, whereas postoperative swelling resolves completely, or almost completely, in 3 months. To facilitate the reduction of swelling, patients are encouraged to perform gentle circular massages of the zone. They may sometimes, but not systematically, be prescribed an abdominal support belt for 6 weeks. In some rare cases, edema may persist longer than expected and endermology treatment is recommended.

At the graft site in the breast

Bruises on the breast resolve in approximately 15 days and swelling in 1 month. There is a progressive reduction of volume by 30%. However, because of initial swelling of the breast immediately after the procedure, the patient may feel that the loss is even greater (around 50%). The volume stabilizes in 3 or 4 months. A higher resorption rate (almost 50%) and a longer stabilization period (5 or 6 months) may be reported in patients with poor fat cell grafts (those for whom the volume of the oily supernatant in the harvested sample is high).

Pitfalls and How to Correct

At the donor site

Scars should be avoided in esthetically sensitive areas. Incisions are generally performed in a natural fold or in the periumbilical region. In our experience, no patient has ever expressed dissatisfaction with her scar. One patient has undergone secondary lipomodeling for the correction of a subtle deficiency in the upper iliac area. Most patients are satisfied with the body contouring associated with the removal of fat in the abdominal region and the thighs, and this secondary benefit most certainly contributes to their overall satisfaction with the procedure.

Cases of local infection are rare; only one of the 850 patients I have treated to date has developed a moderate superficial infection in the umbilical area. The local redness was successfully treated by antibiotics and local application of ice, with no long-term consequences for the patient.

In the breast

Scars must be hardly noticeable. Incisions are usually hidden in the inframammary crease or the axillary fold, or in the periaerolar area where scarring is generally good. No incision should be made in the upper breast quadrant near the sternum which is prone to red marks due to scar hypertrophy. In general, incisions are also barely noticeable because of the very small size (1.5 mm in diameter) of the needle knife.

Only six of my 850 patients have developed an infectious complication in the breast, characterized by localized redness, after breast lipomodeling. On removal of the graft suture, some murky fat dripped off the wound. The infection was easily controlled with antibiotics and local treatment with application of ice, with no long-term consequences for the patients.

Interestingly, in one of our patients (1 in 850 procedures) perioperative desaturation indicated the presence of a pneumothorax, probably due to perforation of the pleura at insertion of the grafting cannula. A pleural drain was inserted while the patient was in the recovery room. Normal saturation was restored and the patient returned to previous clinical condition, with no long-term consequences. To prevent this complication, fat grafting to the periareolar area should systematically be performed upward from two incisions made in the inframammary crease and not from the areola.

Although no case has been reported to date, there is risk of fat embolism when fat is injected in a vessel. Therefore utmost caution is required when injections are made to the subclavian area, notably for patients undergoing lipomodeling for correction of Poland’s syndrome in whom variations from the normal position of subclavian vessels may be encountered.

Clinical features of fat necrosis have been reported in 3% of our patients. All cases corresponded to patients undergoing lipomodeling after latissimus dorsi reconstruction and in whom excess fat cells had been forced into already saturated breast tissues. There is always a risk of fat necrosis in this situation and injections should be discontinued when the tissues at the grafting site are saturated. Fat necrosis lesions are characterized by tenderness to palpation, stability and slowly progressive decrease. Any patient with a progressive enlargement of a firm lesion of the breast (even a reconstructed breast) should have a microbiopsy performed by a skilled radiologist to rule out the risk of developing cancer.

Indications

There are currently many indications for chest–breast lipomodeling, principally for the correction of local defects or the augmentation of breast volume in reconstructed breasts. The technique is particularly recommended for fat transfer in the cleavage area, and to improve the size, the shape, the projection, and the texture of the reconstructed breast. When reconstruction is performed by implantation of a tissue flap, the size of the breast can be increased by injection of fat, while preserving the autologous nature of the procedure. In patients with chest–breast malformations, fat grafting yields very satisfactory natural-looking results, much better than those obtained with common reconstruction techniques, while avoiding recourse to prostheses or flaps. The technique may also avoid recourse to prostheses in patients undergoing cosmetic surgery for breast augmentation or loss of breast fullness after mastopexy, or for the correction of local defects in women who are dissatisfied with the cosmetic results of breast implants.

Lipomodeling of the Autologous Latissimus Dorsi Flap-Reconstructed Breast

When performing breast reconstruction, the objective of plastic surgeons is to obtain symmetry of the reconstructed breast, with a shape and a texture as close as possible to those of the contralateral breast. The use of autologous reconstruction techniques avoids prosthesis-related complications and makes it possible to resculpt the flap until the two breasts are very much alike. Breasts reconstructed with this technique are more stable over time and better fit the body image of the patients. Over the past 10 years, we have progressively substituted autologous latissimus dorsi flap25–27 to TRAM flap reconstruction. Patient postoperative outcome is improved, and the arrangement of tissues is more satisfactory since there is no patch effect due to the presence of a skin flap stretched over the breast. But in some cases, such as very thin patients or patients with postoperative atrophy of the flap, the final size of the breast may be insufficient. To solve this problem surgeons used to secondarily place a prosthesis under the flap, but this upset the autologous nature of the reconstruction, modified the shape of the breast, and resulted in additional risks to the patients. In other cases, although the final shape might be judged satisfactory, breast projection might be found inadequate or locally impaired (principally in the upper-median quadrant corresponding to the cleavage area), thus affecting the results of reconstruction.7,31 Lipomodeling of the breast combined with autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction has many advantages: it makes it possible to preserve the autologous nature of the procedure, to keep the costs relatively low, to reproduce the procedure when necessary, and to create a breast with natural shape and texture and in perfect symmetry with the contralateral breast; finally, a significant secondary cosmetic benefit is associated with liposuction, with the removal of unsightly fat pads at the site harvest.

The latissimus dorsi is the muscle most suitable for fat grafting. The use of this very vascularized tissue flap2,27 restores high neovascularization in the grafted adipocytes, thus facilitating the transfer of large fat volumes. When we first started using this procedure, we used moderate graft volumes between 100 and 120 ml. However, fat necrosis resulted in insufficient final volumes. The procedure was therefore only suitable for the correction of local defects or of soft-tissue deformations in the sternum area. With time and experience, we progressively used much larger volumes of fat, up to 470 ml per breast at a time (which is currently the maximum volume transplanted), with very satisfactory results.

Fat cells are infiltrated in multiple layers from deep to superficial tissues, from the ribs to the pectoralis major muscle, then to the reconstructed breast and the subcutaneous tissues. The procedure involves many incisions and multiple graft tunnels performed following a three-dimensional grid pattern. In areas where soft-tissue coverage is insufficient, repeated grafting sessions, possibly under local anesthesia, are advised. This is why surgeons should make sure that the autologous latissimus dorsi flap wraps the entire breast. The autologous latissimus dorsi flap can thus be seen as a valuable basis for the implantation of fat cells using lipomodeling, particularly in very thin women requiring only a low final breast volume (volume expected at 5 months, after normal atrophy). In these patients, the use of a wide, well stretched-out flap is a prerequisite for efficient fat grafting. For patients in whom the muscle flap is dense, lipomodeling is performed early (at 3 months), before muscle atrophy develops, to take advantage of the muscle volume and inject a sufficient volume of fat cells.

The patients undergoing lipomodeling understand the principles of the procedure and are convinced of its efficacy. This is why it is generally well accepted. Objective morphological assessment indicates very positive results (Figs 12.6 and 12.7). Patients’ satisfaction with the technique which improves the contours of the reconstructed breast and reduces unsightly fat deposits is high. The patients are aware that further attempts may be required when the first treatment has proved insufficient. This step-by-step surgery makes it possible to improve the contours of the breast progressively and to build up a satisfactory final image. In my experience, the non-implant procedure combining lipomodeling with autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction is currently associated with the best results in most patients.7,31

Lipomodeling of the Implant-Reconstructed Breast

There are three major limitations to implant breast reconstruction32 (Fig. 12.8): soft tissue deformities in the sternum area, with visible implant edges in the upper part of the breast and asymmetry between the two breasts, inner defects with capsular contracture and exaggerated cleavage, and finally external defects with a depression on the surface of the breast, just under the anterior axillary fold.

Fig. 12.8 Patient aged 52 years requiring improvement of left breast surgery by implant breast reconstruction. Left lipomodeling (110 ml) and implant replacement; and symmetry of the right breast (60 g breast reduction). Results at 12 months. A preoperative view. B preoperative oblique view. C preoperative markings of lipomodeling area. D postoperative view. E postoperative oblique view.

Based on the encouraging results that we have obtained with lipomodeling after autologous latissimus dorsi flap breast reconstruction, we have applied the same technique to the management of patients with silicone implants. We inject the fat cells in the upper inner quadrant of the breast, near the neckline, principally in the cutaneous pectoris muscle. For defects located in the lower inner quadrant of the breast, lipomodeling is also performed in the pectoral muscle, whereas in patients undergoing prosthesis replacement, fat cells are injected between the capsule and the skin. For patients requiring correction of defects in outer breast quadrants, fat cells are injected between the capsule and the skin, which can only be done at the time of prosthesis replacement.

From our experience we have found that the best results are obtained in patients undergoing lipomodeling at the time of prosthesis replacement. In these patients, lipomodeling successfully overcomes the three major limitations to implant breast reconstruction described above. The volume of fat grafted is smaller: between 50 and 150 ml, depending on the type of tissue and the condition of the pectoralis major muscle. Since the surrounding tissues are less vascularized than when using the autologous latissimus dorsi flap, fewer fat cells are required to ensure successful graft take.

No lipomodeling-related complications have been reported in our patients, given that when fat cells are injected in close proximity of an existing alloplastic implant, we recommend systematic replacement of the implant to avoid cannula-related trauma during the procedure.7,32 Our results indicate good patient acceptance of the technique and also confirm the satisfaction of both the patients and the surgeons with the procedure, a result that would not have been obtained by implant surgery alone. Finally, we believe that lipomodeling is associated with a reduced risk of capsular contracture, though statistical confirmation remains to be obtained.

Lipomodeling of the TRAM Flap-Reconstructed Breast

Although TRAM flap reconstruction is frequently considered the most efficient technique for breast reconstruction, there are also several limitations to its use. In particular, cases of breast asymmetry or lack of projection have been reported, as well as deformities in the sternum area consecutive to pectoral major muscle atrophy after axillary dissection and parietal radiotherapy.

Based on our experience with lipomodeling after autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction, we adapted the technique to the management of TRAM flap reconstruction in our breast cancer patients and in patients requiring secondary correction of breast deformities. For these patients, lipomodeling of both the pectoral muscle and the flap was performed, with particular focus on areas requiring volume replenishment. In some patients, lipomodeling was used to enlarge the overall volume of the flaps, with no particular difficulty. One should remember that the TRAM flap is less vascularized than latissimus dorsi tissues; in consequence, fewer fat cells must be injected to avoid fat cell necrosis.

No complication related to the technique has been observed in our patients. All have reported enhanced overall cosmetic results, with improvement of the upper inner quadrant (Fig. 12.9). Lipomodeling is particularly recommended in case of TRAM flap reconstruction because liposuction of the abdomen and flank regions makes it possible to correct minor imperfections at the abdominal site and to create a more harmonious thoracoabdominal shape. The technique also avoids further displacements of the flap, particularly in patients requiring secondary correction, and thus reduces the risk of necrosis consecutive to secondary flap displacement.

Fig. 12.9 Patient aged 57 years. Breast asymmetry after previous TRAM flap right breast reconstruction. Result at 1 year after 167 ml one-stage lipomodeling of the right breast, and left breast mastopexy. A preoperative view. B preoperative oblique view. C preoperative view of the marking. D preoperative oblique view of the marking. E postoperative view. F postoperative oblique view.

Breast Reconstruction by Repeated Lipomodeling

Following the very encouraging results obtained with breast lipomodeling in our group, we have initiated a clinical study of breast reconstruction with exclusive lipomodeling. The study is aimed at testing the possibility of reconstructing breast by using repeated fat grafts. Accrual is currently limited to patients with a small contralateral breast and abundant supply of fat cells for harvest (typically, women with a slim waist and wide hips). The technique consists of repeated reconstruction courses using exclusively fat cell transplantation (Fig. 12.10). In the indications described above, between three and four lipomodeling sessions are necessary to obtain symmetry with the contralateral breast. The clinical procedure is currently under evaluation, but preliminary results tend to indicate that the procedure is best suited for reconstruction in women with small breast volume or for secondary correction of breast reconstruction failures.

Fig. 12.10 Patient aged 49 years. Delayed right breast reconstruction by lipomodeling after mastectomy and radiotherapy, and after failure of a previous latissimus dorsi flap performed by another surgeon. Results 12 months after fourth lipomodeling session (225 ml, 205 ml, 340 ml, 170 ml). A preoperative view. B preoperative oblique view. C postoperative view. D postoperative oblique view.

Other Applications in Breast Reconstruction

The technique may be used for other types of breast reconstruction, particularly in patients with thin skin coverage or with sequels of radiation therapy considered at risk of skin necrosis at the time of breast reconstruction. Lipomodeling may be performed several months before the reconstruction in order to prepare the breast for the procedure. Between 80 and 120 ml of fat cells are injected into the damaged or severely thinned tissues of the thorax to improve skin trophicity, thus avoiding the occurrence of skin necrosis which may have disastrous consequences in patients undergoing autologous breast reconstruction. Along the same line, it is possible, in patients with borderline indications, to prepare the skin and restore the thickness of subcutaneous tissues before prosthesis implantation. Lipomodeling can also be used for the reconstruction of pre-existing thorax deformities such as lateral pectus excavatum. In these patients, lipomodeling prepares the breast for the second step of reconstruction, which will customize and refine the restoration for each patient’s specific anatomical needs. Finally, the technique may also be used to restore breast symmetry and enhance the cleavage area, notably by injecting fat cells in upper pectoral muscles and breast, or even by slightly increasing the volume of the contralateral breast. In this indication, precise preoperative imaging (mammography and ultrasound) is required, with imaging follow-up at 1 year.

Lipomodeling for the Correction of Breast Conservative Treatment Sequelae

Whereas the technique is now considered validated for the management of patients with total mastectomy, its benefit for the correction of sequelae of breast conservative treatment (lumpectomy and radiation therapy) is currently being assessed under strict scrutiny standards. In this indication, the risk of coincidence with a new breast cancer or a recurrence of the primary tumor is high.33 Very strict control is needed to minimize this risk, which would have potential medico-legal consequences if the patient is not properly informed.33 The protocol includes complete breast imaging34 with mammography, ultrasound, and MRI, performed by a skilled radiologist. Agreement of the radiologist and of the oncologist in charge of the patient (generally the one who referred the patient for plastic intervention) is generally required before lipomodeling is attempted. Breast imaging (mammography and ultrasound) is repeated one year after the procedure for control; in case of doubt, a microbiopsy by the radiologist is recommended. Our study published in 200834 was performed in 42 patients undergoing lipomodeling for the correction of conservative treatment sequelae and included strict imaging follow-up. Findings indicate that fat grafting represents a major advance for the management of moderate sequelae of conservative treatment.35 It makes it possible to restore the shape and softness of the breast to an extent never experienced with previous techniques (Fig. 12.11). The quality of breast imaging is not affected by the procedure and fat grafts do not impair breast cancer detection provided that lipomodeling has been performed in accordance with the rules of the art and that breast imaging is performed by a skilled radiologist.36 However, lipomodeling in this indication may be a delicate issue. This is why we stress the need for a multidisciplinary management for these patients, and reconstruction by plastic surgeons who have acquired sufficient experience and expertise in less severe indications.

Poland’s Syndrome and Lipomodeling

The correction of deformations of the breast and thorax associated with Poland’s syndrome remains a daunting challenge for plastic surgeons. Lipomodeling appears as a promising tool in this indication (Fig. 12.12). Repeated grafting of fat cells to the breast allows excellent restoration of the tissues with limited surgical interventions and scarring.7,31 We have treated 15 patients in total, 13 with exclusive lipomodeling and 2 with lipomodeling and flap reconstruction. The procedure, which required an average of three sessions per patient and 244 ml of transplanted fat per session, produced very interesting results. It was possible to restore the injured breast and to give it a shape almost identical to that of the contralateral breast. The introduction of this technique appears as a major breakthrough for the management of thorax and breast deformations in Poland’s syndrome.7,31

Pectus Excavatum and Lipomodeling

Pectus excavatum is a complex deformity in which the depression of the sternum and adjacent ribs results in a sunken chest wall. The functional abnormality induced is generally mild or null. Most patients principally exhibit difficulties stemming from morphological and esthetic concerns. If pectus excavatum is severe or the deformity is restricted to one side of the chest, it may affect the shape of the patient’s breast. Fat transfer can provide satisfactory results in this indication, either alone in patients with moderate or mild deformity, or in combination with patient-tailored silicone prosthesis (adapted from three-dimensional CT-scan images) for more severe forms.

Tuberous Breasts

Tuberous breast deformity is an uncommon breast anomaly associated with a constriction in the lower pole of the breast. It becomes apparent at puberty with the growth of breast. Several surgical methods have been described to correct this deformity, and a wide range of options are available, all with very positive results. Lipomodeling7,31 can be used to compensate for the lack of volume (especially if the defect affects only one of the breasts) and to improve the lower pole and the general shape of the breast (Fig. 12.13). Lipomodeling thus appears as a very interesting complementary approach in this indication. Recently, Coleman37 has reported very encouraging results in patients with tuberous breast deformity treated by fat grafting.

Fig. 12.13 Patient aged 28 years with type 2 tuberous breasts. Treatment of the deformity with sessions of lipomodeling (right breast (253 ml, 320 ml), left breast (90 ml, 210 ml)). Results at 4 months after the second procedure. A preoperative view. B preoperative oblique view. C preoperative oblique view. D postoperative view. E postoperative oblique view. F postoperative oblique view.

The best indication for this approach is the treatment of unilateral tuberous deformity (generally, two grafting sessions are required) and upper pole expansion. Otherwise, breast implants remain usually the standard treatment for bilateral tuberous deformities with severe hypotrophy (because of the need of large fat volume from the donor sites).

Breast Asymmetry

Compensation for breast asymmetry is difficult when one breast is normal in shape and volume (Fig. 12.14) and the other breast is very hypotrophic. The standard treatment is the placement of a prosthesis to enlarge the small hypotrophic breast. Results are generally satisfactory, though asymmetry (both in form and volume) generally reappears after several years. In this indication, lipomodeling can be used to re-sculpt the hypotrophic breast and restore a shape and volume very similar to those of the normal breast. The treatment allows for very natural evolution over time and normal ptosis. One to three grafting sessions (usually two) are required, depending on the extent of the asymmetry and the degree of hypotrophy.

Fig. 12.14 Patient aged 26 years with significant asymmetry. Treatment of the deformity with 2 sessions of lipomodeling to the right breast (312 ml, 144 ml). Results at 3 months after the second procedure. A preoperative view. B preoperative oblique view. C postoperative view. D postoperative oblique view.

Breast Aesthetic Surgery

There is a consistent increase of the use of breast lipomodeling for aesthetic purposes. Our studies have shown that, when using the technique as described here, there is no risk of mammographic changes interfering with breast cancer detection or with the radiological follow-up of the patients by radiologists skilled in breast imaging. The major medico-legal issue is the possible co-occurrence of a breast tumor in a patient undergoing lipomodeling. To mitigate this risk, a complete imaging evaluation of the patient (mammography and ultrasound) by a skilled radiologist is required before initiation of the procedure to check for suspicious lesions. Agreement by the radiologist is a prerequisite. In case of doubt, lipomodeling is adjourned or deemed contraindicated. The radiologist shares the responsibility for the patient’s care in his own domain, whereas the patient must give written consent to undergo testing with the same radiologists at 1 year after the procedure. If a radiographic abnormality is detected at the time of the control, a biopsy should be systematically performed to ensure that there is no evidence of cancer. Complete patient information is of particular importance in this indication, and the surgeon must make sure that the patient reads the specific documents given during the preoperative visits.

Aesthetic lipomodeling is indicated for the correction of defects after mammaplasty or the treatment of prosthesis-related complications, and for patients requiring aesthetic breast augmentation. Contrary to prosthesis implantation, lipomodeling is used for patients who require only moderate, or very moderate, breast augmentation, or for those who wish to recover their former breast size, after weight loss or pregnancy, for instance. The technique is particularly indicated for women who have a slim upper body with moderate breast hypotrophy and wide hips with sufficient fat cells for one or two lipomodeling sessions. To ensure maximum benefit, lipomodeling must necessarily produce a slimming effect at the donor site and the patient must be at her ideal weight otherwise, if she loses weight, the benefit of the procedure might be lost.

Contraindications

Contraindications are rare. They apply principally to very thin patients who do not have enough fat tissue for harvest. As a rule, there is 30% cell loss during centrifugation and preparation of the graft, and again a 30% cell loss in the 4 months following the transplantation, principally due to cell resorption. Therefore, only patients with sufficient fat reserves can be eligible for lipomodeling.

In some cases, contraindication is only relative: the patient can undergo fat cell harvest but the procedure is longer and more complex than usual.

Lipomodeling is temporarily contraindicated in patients with pre-existing cytosteatonecrosis, since cells collected from areas of fat necrosis are generally not optimal for graft take. Depending on the extent of the necrosis, the situation will either resolve spontaneously or with massage or, for larger (several centimeters) lesions not likely to resolve by themselves, with liposuction and fragmentation of fat necrosis.

Conclusion

Lipomodeling, or fat grafting, is among the most significant advances in breast plastic surgery over the past 20 years.

For breast reconstruction, the technique is complementary to other methods such as, for instance, autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction. In this case, the composite fat-muscle flap is an ideal recipient for the graft. In most cases, the combination of lipomodeling with autologous latissimus flap reconstruction is a completely autologous reconstruction method. Only few, very thin patients with little fat deposits available for collection are excluded from the procedure.

Along the same line, lipomodeling can also be used in patients undergoing breast reconstruction with silicone implants. It is generally best suited at the time of prosthesis replacement. The technique can also be used for cosmetic corrections after TRAM flap or deep inferior epigastric artery perforator reconstruction, notably for deformities of the upper breast quadrant. The use of lipomodeling in these indications is daily routine for us.

In the future, it would be interesting to explore the use of repeated exclusive lipomodeling for breast reconstruction. There are several limitations to the use of the technique, notably the procedure is long and can only be used in patients with limited breast volume and large fat deposits at trochanter sites allowing multiple harvests. Its contribution to breast reconstruction is currently under evaluation and clinical validation is awaited.

The use of lipomodeling for the correction of chest and breast deformities is rapidly increasing. In patients with severe Poland’s syndrome, the procedure seems highly beneficial, with high quality reconstruction, moderate scarring and acceptable surgical trauma; it should revolutionize the management of this disease. It is also useful for the correction of chest deformity in patients with lateral pectus excavatum, and can be used as a complementary tool for patients with median pectus excavatum undergoing anatomical correction. Finally, lipomodeling is a promising treatment alternative for patients with tuberous breasts and for autologous correction of asymmetry in patients with unilateral breast hypotrophy.

In conclusion, lipomodeling should be more and more widely used in aesthetic surgery. It is useful for the correction of aesthetic contour problems after mammaplasty, for the treatment of prosthesis-related defects or complications, as well as for moderate natural-like aesthetic breast augmentation in patients with abundant fat reserves. Pre- and postoperative workup by a radiologist skilled in breast imaging is required to reduce the risk of breast cancer going undiscovered at the time of the lipomodeling procedure.

1 Illouz YG. La sculpture chirurgicale par lipoplastie. Paris: Arnette; 1988.

2 Fournier PF. The breast fill. In: Fournier PF, editor. Liposculpture the syringe technique. Paris: Arnette Blackwell; 1991:357-367.

3 Bircoll M. Cosmetic breast augmentation utilizing autologous fat and liposuction techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:267-271.

4 Coleman SR. Long-term survival of fat transplants: controlled demonstrations. Aesth Plast Surg. 1995;19:421-425.

5 Coleman SR. Facial recontouring with lipostructure. Clin Plast Surg. 1997;24:347-367.

6 Delay E, Delaporte T, Sinna R. Alternatives aux prothèses mammaires. Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 2005;50:652-672.

7 Delay E. Lipomodeling of the reconstructed breast. In: Spear SE, editor. Surgery of the breast: principles and art. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:930-946.

8 Czerny V. Plastischer ersatz der brustdrüse durch ein lipom. Zentral Chir. 1895;27:72.

9 Sinna R, Delay E, Garson S, Mojallal A. La greffe de tissu adipeux: mythe ou réalité scientifique. Lecture critique de la littérature. Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 2006;51:223-230.

10 May H. Transplantation and regeneration of tissue. Peen Med J. 1941;45:130.

11 Bames HO. Augmentation mammoplasty by lipo-transplant. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1953;11:404-412.

12 Longacre JJ. Use of local pedicle flaps for reconstruction of breast after subtotal or total extirpation of mammary gland and for correction of distortion and atrophy of the breast due to excessive scar. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1953;11:380-403.

13 Schrocher F. Fetgewerbsverpflanzung bei zu kleiner brust. Munchen Med Wochenschr. 1957;99:489.

14 Hang-Fu L, Marmolya G, Feiglin DH. Liposuction fat-fillant implant for breast augmentation and reconstruction. Aesth Plast Surg. 1995;19:427-437.

15 Pohl P, Uebel CO. Complication with homologous fat grafts in breast augmentation surgery. Aesth Plast Surg. 1985;9:87.

16 Rosen PB, Hugo NE. Augmentation mammaplasty by cadaver fat allografts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:525-526.

17 Bircoll M, Novack BH. Autologous fat transplantation employing liposuction techniques. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;18:327-329.

18 Hartrampf CRJr, Bennett GK. Autologous fat from liposuction for breast augmentation (letter to the editor). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:646.

19 Ettelson CD. Fat autografting (letter to the editor). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:646.

20 Linder RM. Fat autografting (letter to the editor). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:646.

21 Ousterhout DK. Breast augmentation by autologous fat injection (letter to the editor). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:868.

22 Bircoll M. Reply (correspondence). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:647.

23 Bircoll M. Autologous fat transplantation to the breast. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:361-362.

24 Brown FE, Sargent SK, Cohen SR, Morain WD. Mammographic changes following reduction mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:691-698.

25 Delay E, Gounot N, Bouillot A, Zlatoff P, Comparin JP. Reconstruction mammaire par lambeau de grand dorsal sans prothèse. Expérience préliminaire à propos de 60 reconstructions. Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 1997;42:118-130.

26 Delay E, Gounot N, Bouillot A, Zlatoff P, Rivoire M. Autologous latissimus breast reconstruction. A 3-year clinical experience with 100 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:1461-1478.

27 Delay E. Breast reconstruction with an autologous latissimus flap with and without immediate nipple reconstruction. In: Spear SE, editor. Surgery of the breast: principles and art. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:631-655.

28 Pierrefeu-lagrange AC, Delay E, Guerin N, Chekaroua K, Delaporte T. Evaluation radiologique des seins reconstruits ayant bénéficiés d’un lipomodelage. Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 2006;51:18-28.

29 Delay E, Delaporte T, Jorquera F, El Berberi N, Vasseur C. Lipomodelage du sein reconstruit par lambeau de grand dorsal sans prothèse. 46ème congrès de la Société Française de Chirurgie Plastique, Esthétique et Reconstructrice. Paris. 17–9 October 2001.

30 Delay E, Chekaroua K, Mojallal A, Garson S. Lipomodeling of the autologous latissimus reconstructed breast. 13th International Congress of the International Confederation for Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery. Sydney, 10–15 August 2003, Abstr in. ANZ J Surg, 73. 2003:A170.

31 Delay E. Breast reconstruction. In: Coleman SR, Mazzola RF, editors. Fat injection: from filling to regeneration. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing (QMP); 2008:545-586.

32 Delay E, Delpierre J, Sinna R, Chekaroua K. Comment améliorer les reconstructions par prothèses? Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 2005;50:582-594.

33 Gosset J, Flageul G, Toussoun G, Guerin N, Tourasse C, Delay E. Lipomodelage et correction des séquelles du traitement conservateur du cancer du sein. Aspects médico-légaux. Le point de vue de l’expert à partir de 5 cas cliniques délicats. Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 2008;53:190-198.

34 Delay E, Gosset J, Toussoun G, Delaporte T, Delbaere M. Efficacité du lipomodelage pour la correction des séquelles du traitement conservateur du cancer du sein. Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 2008;53:153-168.

35 Delay E, Gosset J, Toussoun G, Delaporte T, Delbaere M. Séquelles thérapeutiques du sein après traitement conservateur du cancer du sein. Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 2008;53:135-152.

36 Gosset J, Guerin N, Toussoun G, Delaporte T, Delay E. Aspects radiologiques des seins traités par lipomodelage après séquelles du traitement conservateur du cancer du sein. Ann Chir Plast Esthét. 2008;53:178-189.

37 Coleman SR, Saboeiro AP. Fat grafting to the breast revisited: safety and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:775-785.

CHAPTER 12 Fat Injections to the Breast

The Lipomodeling Technique

Summary/Key Points

Introduction

Transferring fat from parts of the body where it is in excess to the breast for cosmetic and esthetic purposes has been a long-lasting objective, and probably also a long-lasting dream.

This approach has been considered since the very beginning of liposuction, particularly after the publication of the works of Illouz1 and Fournier.2 However, it remained controversial and was not widely used until the development of more precise tools and techniques. It was feared that autologous fat transfer would generate fat necrosis and calcifications which, at that time, were not readily assessable because of the limitations of existing imaging modalities.

The final blow came in 1987. After the presentation of a case by Bircoll,3 the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons recommended to stop using fat tissue injections for breast augmentation. The technique regained popularity after confirmation by Coleman4,5 that fat tissues could be transplanted safely provided that adequate care is given to the preparation and transfer of fat cells. In 1998, given the proven efficacy of fat transfer to the face for facial rejuvenation or post-surgery reconstruction, we developed a research program aimed at evaluating the efficacy of the procedure for thoracomammary reconstruction. We developed the technique named ‘lipomodeling’,6,7 then assessed its efficacy and tolerability in patients and demonstrated the absence of clinical or radiological signs of adverse effects.

The objective of the present chapter is to examine the history and illustrate the progression of knowledge about the lipomodeling technique used in our unit, to describe indications, contraindications, as well as potential complications associated with its use, and finally to provide input regarding the most effective means of preventing or resolving these problems.

History of the Technique and Progression of Ideas

First attempts

Fat grafting for breast plastic surgery has long been advocated by prominent surgeons. In 1895, at the German Congress of Surgery, Czerny described the first clinical case of breast reconstruction by transplantation of a giant lipoma of the lumbar region to the breast. Adipose cells were used to fill the void left in the breast after tumor resection in a patient with a fibroadenoma.8,9 Some surgeons thereafter performed breast reconstruction or augmentation using fascio-cutaneous flaps,10 gluteus fat implants,11 or local pedicle flaps.12 Injections of fat either directly into the breast1,2,13 or into previously inserted implants14 have also been reported. Some authors have even described the cases of women undergoing augmentation mammaplasty by cadaver fat allografts.15,16

Liposuction experiments published by Illouz1 contributed to the development of the technique and to the worldwide generalization of the concept. It became tempting to use autologous fatty tissues collected by liposuction for breast augmentation, as primarily done by Illouz. Similarly, in 1991, Fournier described the fat-grafting technique which he used only in patients who refused prostheses and who desired only moderate breast augmentation.2 The quantity of fat grafted to the patients was between 100 and 250 ml in each breast, injected in the retroglandular space, not in the mammary parenchyma.

At the time, many surgeons viewed the new procedure with skepticism. The technique had not been standardized and it was not possible to guarantee the absence of fat necrosis following fat transfer. Breast imaging techniques were not as accurate as they are today; any mammary tumefaction could cause mammographic changes and give rise to diagnostic confusion, and there was a fear that areas of fat necrosis might interfere with breast cancer detection.

The controversy

Fat grafting to the breasts has been highly controversial since the presentation by Bircoll, first in Bangkok in 1984, then at the California Society of Plastic Surgeons in 1985, of a case undergoing breast augmentation by injection of fat cells obtained by liposuction. The patient was a 20-year-old woman who requested a moderate augmentation of her breast while undergoing fat grafting to repair the damages caused by a dog bite. Bircoll3 considered the technique should only be used for women requesting moderate augmentation because of the potential risk of necrosis when grafting large quantities of fat. He reported the main advantages of the procedure: simplicity, absence of scar, early recovery, avoidance of prosthesis use and thereby of prosthesis-related complications, as well as the positive slimming impact at the site of fat removal. In April 1987,17 Bircoll reported the case of a patient undergoing bilateral fat grafting after unilateral reconstruction by transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM; improved aesthetic results and symmetry). The two papers triggered controversial reactions from the medical community18–21 who deplored that autologous fat injections in the breasts could generate microcalcifications and cysts, possibly interfering with the detection of early breast carcinoma. Bircoll argued22,23 that cancer-related calcifications and those consecutive to fat transplantation occur in different sites and have different radiological aspects, and therefore cannot be mistaken, and that breast reduction surgery also is responsible for microcalcifications, but the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons stated:

The committee is unanimous in deploring the use of autologous fat injection in breast augmentation, much of the injected fat will not survive, and the known physiological response to necrosis of this tissue is scarring and calcification. As a result, detection of early breast carcinoma through xerography and mammography will become difficult and the presence of disease may go undiscovered.

There was no explicit reference to scientific findings and the report only expressed the opinion of the members of the committee. Despite the paucity of scientific information and although it had long been recognized that any mammary surgery can be responsible for the occurrence of fatty cysts or mammographic changes, the injection of fat into the breasts became taboo among surgeons. The ASPRS banning put an end to any research or experimentation on the subject.

Ironically, in 1987, a retrospective study of the mammographic changes after breast reduction published in the same journal24 reported that calcifications were detectable in 50% of all mammograms at 2 years from surgery. The author insisted that in most cases these benign calcifications were easily distinguishable from cancer. Despite this high incidence and the risk for mammography abnormalities to interfere with cancer detection, there was no discussion of discontinuing breast reductions.

Progressive lifting of the taboo

The demonstration of the efficacy of fat transfer, based on atraumatic fat harvesting and injection, for facial rejuvenation and for the correction of facial deformities4,5 prompted us to adapt the technique to breast reconstruction. The contribution of fat grafting to the thorax and the breast for breast reconstruction has been one of our principal research topics over the past ten years. First, we used fat grafting along with autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction. This method, previously developed by our surgical unit,25–27 allowed satisfactory reconstruction in 70% of the cases. However, the other 30% resulted in insufficient breast volume and reduction of the contralateral breast was needed, or else insertion of a prosthesis; in this case, the procedure was no longer autologous and the patients suffered the drawbacks of prostheses (unnatural shape and texture, and obligation to change the prosthesis after a while). We started using fat grafting in breast cancer patients undergoing autologous latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction who were at low risk of local recurrence. We named the technique ‘lipomodeling,’ from the Greek root lipo for fat, and the Latin word modello which means to give shape or volume, which is exactly the objective of this procedure. At first, only volunteer patients who agreed to undergo strict follow-up were operated on. Then, after the demonstration of the efficacy of the technique, we proposed it to almost all patients treated by latissimus dorsi flap reconstruction. Fat grafting provides them with optimal breast shape and texture as well as a natural cleavage. The study of mammography, computed tomography (CT)-scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings conducted in parallel28 demonstrated that the impact of lipomodeling on the patient’s images was far from negative. It was thus progressively extended to other indications of breast reconstruction, then to the correction of breast deformities, to the treatment of sequelae of conservative treatment and, more recently, to breast cosmetic surgery.

Our first presentations28,29 raised considerable controversy, similar to criticisms made in 1987. Point-by-point debate gradually won over the hostility of the clinical community and fat grafting has now become a standard procedure in breast reconstruction.7,30,31

Operative Technique6,7,31

Preparation

The patients are given information about the technique and about possible risks and complications. Each patient receives one of four information leaflets corresponding to her situation: ‘Lipomodeling in breast reconstruction,’ ‘Lipomodeling for the correction of breast conservative treatment sequelae,’ ‘Lipomodeling for the correction of breast malformations,’ and ‘Aesthetic breast lipomodeling.’

It is essential that the patient be at her ideal weight at the time of lipomodeling. Fat cells have a memory of their origin and, if the patient loses weight after the procedure, grafted cells may not survive.

Careful clinical examination of the breast areas to be treated is required. They are identified and marked on the skin before the operation (Fig. 12.1). In addition to commonly used two-dimensional images, three-dimensional morphological images are taken and compared to evaluate the quantity of fat that should be grafted and estimate fat resorption.

The various fatty areas in the patient’s body are examined to identify and locate natural fat deposits. Usually, the fat cells used for lipomodeling are those taken from the abdominal region. The patients are satisfied with the local thinning effect; and also, the procedure is easy for the surgeons since it is not necessary to change the patient’s position between collection and grafting. The second most frequent site for fat harvest is the trochanter (flabby thighs), and the inner side of the thighs and knees. Areas of fat harvest are visualized and marked with skin-marking pen (Fig. 12.2).

Anesthesia

Successful breast reconstruction requires sufficient quantities of fat cells and the harvesting procedure is somewhat long. This is why most patients undergoing lipomodeling are placed under general anesthesia. In breast cancer patients undergoing postmastectomy reconstruction, the procedure is associated with nipple–areola reconstruction and contralateral breast symmetry. As is generally recommended in our unit for patients undergoing plastic surgery, perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is given to all patients. No lipomodeling-specific antibiotic treatment is given.

Local anesthesia is considered only for patients requiring moderate lipomodeling, generally for secondary management of a residual scar.

Incisions

Fat is harvested by making incisions with a No. 15 blade: four periumbilical incisions are performed for collecting abdominal deposits, and two lateral incisions (one on each side) for lateroabdominal or suprailiac deposits. Fat cells in the thighs are removed through incisions in the buttock fold (one on each side), and frequently also in the inner side of the knees.

When the patient requiring lipomodeling has had previous surgery to the breast, the procedure can be performed through the same incisions. In total, five or six incisions are made to reduce the convergence of graft tunnels: at least two in the inframammary fold and one in the upper breast quadrant. To keep scars to a minimum, incisions are generally made with the beveled edge of a cutting blade.

Fat harvesting

Recent work in the field has contributed to the standardization of the methods to be used for fat harvesting and grafting, and for the limitation of hazards at each step of the procedure. Only a strict observation of the rules at the different steps can ensure satisfactory median and long-term fat cell survival.4–79 Fat is harvested using a disposable cannula or a Coleman harvesting cannula. These blunt-tipped cannulas are inserted through 4 mm incisions made with a No. 15 blade, and directly attached to a 10 ml Luer-lock syringe. Fat cells are collected by moderate aspiration (Fig. 12.3) to minimize trauma on the adipocytes and improve the number of viable transplanted cells. The volume of fat aspirates must be enhanced to account for the cell loss incurred by centrifugation, refinement and transplantation.

Fig. 12.3 Fat cell collection. A Disposable harvest cannula. B Fat cell collection using a disposable harvest cannula attached to a 10 ml Luer-lock syringe.

For better cosmetic results, the areas where fat cells have been harvested are smoothed by classical liposuction with a 4 mm cannula. Skin incisions are sutured with absorbable stitches.

Conditioning of the graft

During fat harvesting, a surgical assistant prepares the cells for centrifugation by placing a screw cap on the extremity of each syringe (Fig. 12.4), then syringes are subjected to 3-minute centrifugation at 3200 rpm (Fig. 12.4). Six syringes can be processed at a time.

Fig. 12.4 Preparation of the fat cells.

A Placement of a screw cap on top of the syringe. B Centrifugation of syringes (six syringes at a time). C Centrifugation separates the graft into three layers. Only the layer containing purified fat cells is reinjected to the patient. D Elimination of the bottom layer (serum and residues) by opening the cap.E Elimination of the upper layer (oily supernatant). F Transfer from one syringe to another using a three-way tap; 10 ml of pure fat cells are collected.

During centrifugation, harvested fat cells are separated into three layers (Fig. 12.4C):

Careful planning is necessary to ensure efficient and rapid preparation of the fat graft. Fat cells are transferred from one syringe to the other using a three-way stopcock, then collected into 10 ml fractions (Fig. 12.4F).

Placement of the fat graft

When all fat samples have been processed, a number of 10 ml syringes of purified fat aspirates are available. The fat is then transferred directly from the 10 ml syringes to the breast area by adapting specific disposable cannulas of 2 mm diameter. These cannulas (Fig. 12.5A) are slightly longer and more resistant than those used for fat grafting to the face because higher mechanical constraints are associated with injection of fat into more solid and more fibrous tissues.

Fig. 12.5 Placement of the fat graft.

A Disposable transplantation cannula specific for lipomodeling. B Breast incision with a 17G needle knife. C Modalities of fat transfer: injection of small, spaghetti-like strips of fat while pulling the cannula back. D Fat transfer to the breast.

Incisions to the breast are performed using a 17 gauge needle knife (Fig. 12.5B). These small incisions allow for the passage of the cannula while limiting the impact of scarring and preserving the cosmetic results of the procedure which becomes almost invisible with time. Multiple small incisions, positioned to allow accurate placement of graft tunnels in different radial directions are required to ensure correct shaping.

It is recommended to inject the fat in small spaghetti strips (Fig. 12.5C), in multiple layers and multiple directions, from deep to superficial tissues (Fig. 12.5D), following a three-dimensional grid pattern. A good spatial representation of the area is required to avoid injecting large fat clumps potentially responsible for fat cell necrosis. On the contrary, each aliquot must be injected in a well-vascularized area, at a distance from other injection sites, and under low pressure (while gently pulling the cannula back).

The volume of fat transferred to the patient must be overestimated (whenever possible) to account for 30% fat resorption after injection. As a rule, one must graft at least 140 ml of fat cells to obtain a final volume of 100 ml.