CHAPTER 26 Fat Injections

Key Points

Introduction

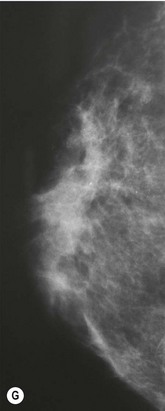

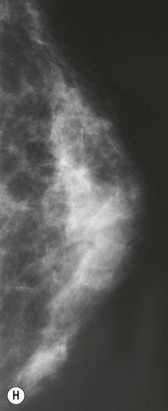

Autologous fat transplantation is one of the promising cosmetic treatments for facial rejuvenation and soft-tissue augmentation due to the lack of an incisional scar and complications associated with foreign materials. However, certain problems remain, such as unpredictability and a low rate of graft survival due to partial necrosis. It has also been used in breast augmentation by a limited number of plastic surgeons,1 although the use of autologous fat for breast augmentation has been controversial due to the lack of consensus on whether it is safe and appropriate because of microcalcifications that may cause confusion in the evaluation of mammograms.

Implantation of prostheses has been a gold standard for breast augmentation, but complications with artificial materials such as capsular contracture remain to be resolved. The presence of the implant and capsules induced by implants could also affect breast tissue visualization in the mammogram.2 Furthermore, there is potential for rupture when pressure is exerted on the implant during mammography, and for this reason, hospitals in Japan reject women with breast implants to undergo mammography as a part of the annual social health examinations. Recently, autologous fat injection has been re-evaluated as a potential alternative to artificial implants for breast augmentation.1,3 This re-evaluation may reflect recent advances in autologous fat transfer and the radiological detection of breast cancer.

In this chapter, potentials of fat injection for breast augmentation or reconstruction are discussed as well as our novel approach of autologous fat grafting called cell-assisted lipotransfer (CAL);3,4 this is the concurrent transplantation of aspirated fat tissue and adipose progenitor cells.

Patient Selection

There are several patient factors that may affect the clinical result of conventional lipoinjection or CAL: skin redundancy of the breasts, age, body mass index (BMI), individual quality or character of the fat tissue, adhesive scars, breast implant and its capsule, systemic disease such as autoimmune disease, oral corticosteroids, etc.3,5 Good candidates are those who have sufficient fat at donor sites and redundant breast skin with healthy vascularity and without any scars.

Indications

Graft tissue preparations

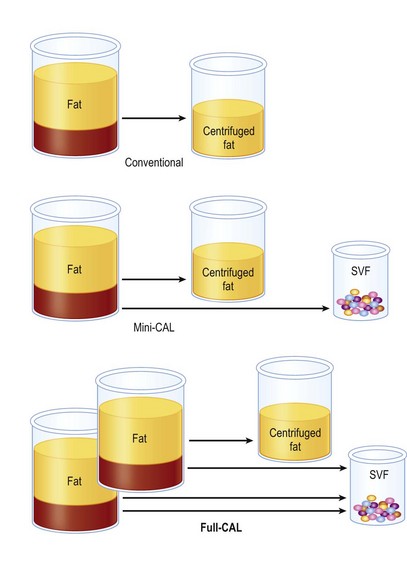

As for lipoinjection, we use conventional lipoinjection (micro-fat grafting) and a new technique; grafting of progenitor-enriched adipose tissue. We call the latter CAL; the concept and details of CAL are described later. There are two types of CAL: mini-CAL and full-CAL; only the fluid portion of liposuction aspirates are used for harvesting adipose progenitor cells in mini-CAL, while another similar volume of liposuction aspirates to graft tissues are used for the cell isolation in full-CAL (Fig. 26.1). Thus, full-CAL requires twice the volume of adipose tissue as the conventional lipoinjection or mini-CAL; approximately 700–800 ml of lipoaspirate are needed for conventional lipoinjection or mini-CAL for both breasts, while 1200–1500 ml lipoaspirate are required for the full-CAL procedure.

Fig. 26.1 Scheme of conventional lipoinjection and cell-assisted lipotransfer (CAL).

The adipose portion (yellow) of liposuction aspirates is centrifuged and used as injection material in conventional lipoinjection. In mini-CAL, the fluid portion (pink) of the liposuction aspirate is used for the isolation of the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) containing adipose progenitor cells. In full-CAL, another volume of liposuction aspirate is additionally harvested for SVF isolation. Freshly isolated SVF are used for supplementation of adipose progenitor cells to grafting tissues. (For the supplementation of SVF, see also Figure 26.5.)

Operative purposes

Injection of progenitor-enriched fat tissue: principles and therapeutic concepts of CAL

Cell components of adipose tissue

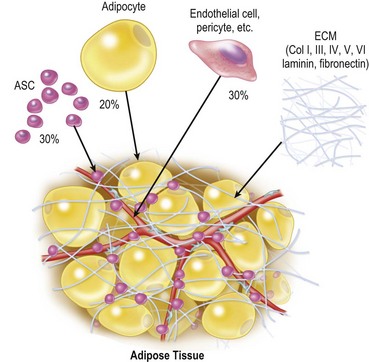

Adipose tissue consists predominantly of adipocytes, adipose stromal cells (ASC), vascular endothelial cells, pericytes, fibroblasts and extracellular matrix.6 Adipocytes constitute more than 90% of tissue volume, but they are much larger in size than the other cells and the number of adipocytes is estimated to be less than 50%7 (Fig. 26.2). ASC are considered to be adipose tissue-specific progenitor cells (adipogenic and angiogenic progenitors), some of which have been shown to differentiate into multiple lineages and are now called adipose-derived stem cells.8 ASC contribute to adipose tissue turnover (adipose tissue is thought to turn over every 2–10 years9,10) and provide cells for the next generation. ASC are currently being used in various clinical trials, including treatments for rectovaginal fistula (autologous cultured ASC)11 and graft-versus-host disease (non-autologous ASC).12 If ASC are harvested from a large volume (e.g., 500 ml) of liposuction aspirates, ASC can be used clinically without cell expansion because a sufficient number of cells can be obtained. The use of minimally manipulated fresh cells may lead to higher safety and efficacy in actual treatments.

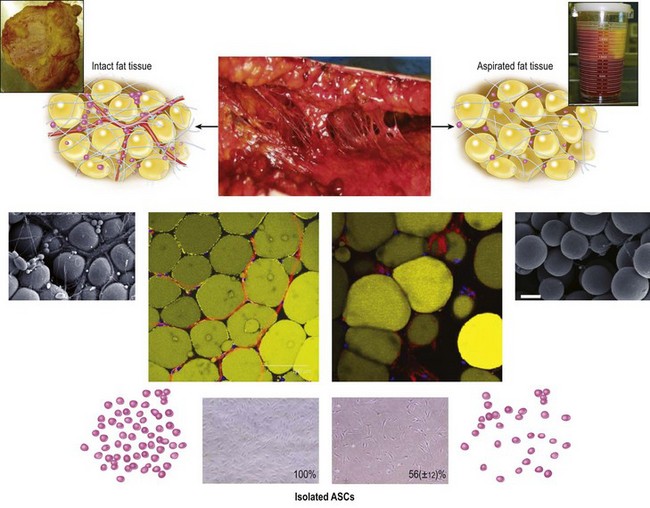

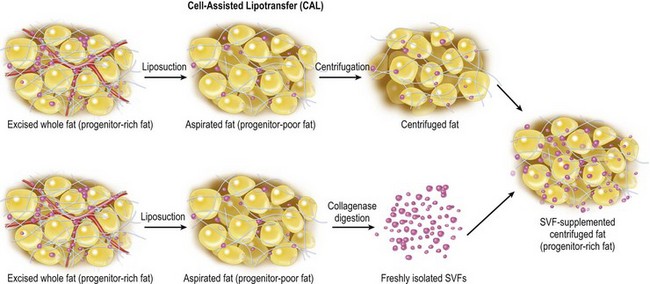

Aspirated fat tissue versus intact fat tissue

We can use aspirated fat tissue as lipoinjection material but not excised fat tissue. Aspirated fat is fragile parts of the adipose tissue taken with negative pressure. Our research revealed that aspirated fat tissue contains only half the number of ASC compared to intact fat tissue4 (Fig. 26.3). The two main reasons for this relative deficiency of ASC contained in aspirated fat tissue are: (1) a major portion of ASC are located around large vessels (within the tunica adventitia) and left in the donor tissue, and (2) some ASC are released into the fluid portion of liposuction aspirates.6 Our histological study indicated that ASC are located not only between adipocytes but also around vessels. Large-sized vessels are located in the fibrous part of the tissue, which contains intact fat tissue but not aspirated fat tissue. Thus, aspirated fat tissue is regarded as relatively progenitor-poor fat tissue compared to intact fat tissue.4

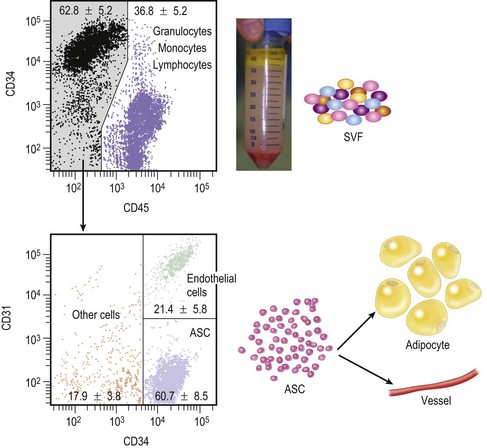

Stromal vascular fraction

Through collagenase digestion a heterogeneous cell mixture, which contains cell types other than adipocytes, can be extracted from adipose tissue as a cell pellet. This cell fraction is called the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) (Fig. 26.4), because they are basically stromal cells and contain vascular endothelial and mural cells. In the clinical setting SVF contains a substantial amount of blood-derived cells, such as leukocytes and erythrocytes, as well as adipose-derived cells such as ASC and vascular endothelial cells.6 Our study revealed that nucleate cells contained in the SVF are composed of 37% leukocytes, 35% ASC, 15% endothelial cells and other cells, though the percentage of blood-derived cells strongly depends on individual hemorrhage volume.7 In CAL, the freshly isolated autologous SVF is used as a supplementation for fat graft tissue without any manipulations such as cell sorting or cell culture.3,5

Concept of CAL

Aspirated fat tissue has a significantly lower progenitor/mature-cell ratio as mentioned above, and this low ASC/adipocyte ratio may be the main reason for long-term atrophy of transplanted adipose tissue. There are at least three experimental studies, including ours,4,13,14 demonstrating that supplementation of adipose progenitor cells enhances the volume or weight of surviving adipose tissue. Enrichment of adipose progenitor cells by supplementation of SVF improves progenitor/adipocyte ratio; progenitor-poor aspirated fat tissue will be converted to progenitor-rich fat tissue. In CAL, freshly isolated SVF, which contains ASC, is supplemented to progenitor-poor aspirated fat tissue; the cells are attached to the aspirated fat with the fat acting as a living bioscaffold before transplantation (Fig. 26.5).

Fig. 26.5 Scheme of cell-assisted lipotransfer (CAL). Relatively progenitor-poor aspirated fat tissue is converted to progenitor-rich fat tissue by supplementation with the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) isolated from one-half of the aspirated fat sample. (Strictly speaking, the source of SVF differs between mini-CAL and full-CAL; see also Figure 26.1 for the difference.) SVF cells are attached to the aspirated fat tissue, which acts as a scaffold in this strategy.

Transplanted adipose tissue undergoes ischemia and subsequent reperfusion as well as high internal pressure by edema and inflammatory changes in the host tissue. The microenvironments, injury-associated growth factors, and inflammation-associated cytokines and chemokines would influence ASC behaviors during the acute phase of tissue repair.15 Adipose grafts undergo adipocyte and capillary remodeling, and ASC are a main cell population functioning in the repairing process of the adipose tissue.15 The relative deficiency of ASC in aspirated fat tissue may affect the replacement process and lead to postoperative atrophy of grafted fat, which is known to commonly occur during the first 6 months after lipoinjection.

Operative Technique

Surgical procedures

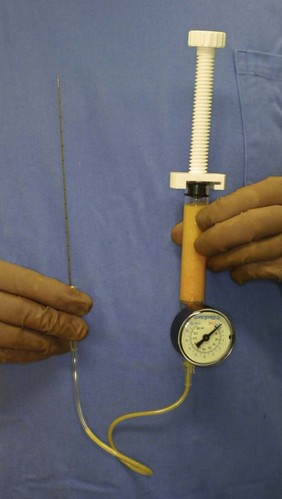

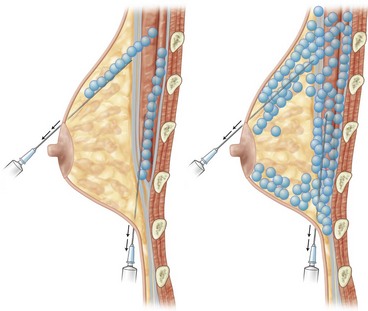

Basic breast augmentation

For the injection syringe, a 10 ml LeVeen inflator (Boston Scientific Corp., MA) or our original syringe (20 ml) is used because they are screw-type syringes (with a threaded plunger) and threaded connections that fit both the connecting tube and the needle, to allow for precise control during injection (Fig. 26.6). To reduce the time of the procedure, two syringes are used; while one syringe is being used for an injection, the other is filled with the graft material in preparation for the next injection. A 16- or 18-gauge needle (150 mm long) is used for lipoinjection and inserted subcutaneously from the inframammary fold or areolar margin (Fig. 26.7). The operator takes care to insert and place the needle horizontally (parallel to the body), in order to avoid damaging the pleura and causing a pneumothorax. The needle is inserted in several layers and directions, and is continuously and gradually retracted as the plunger is advanced (Fig. 26.7). This technique is used to obtain a diffuse distribution of the graft material. The grafts are placed into the fatty layers on, around, and under the mammary glands (but not intentionally into the mammary glands), and also into the pectoralis muscles. After training, it is not hard for an operator to recognize the mammary gland or pectoralis fascia as a harder tissue than the fat or muscle tissue. Injection is discontinued when the skin becomes tense; the average volume of injection is 250–300 ml for each breast.

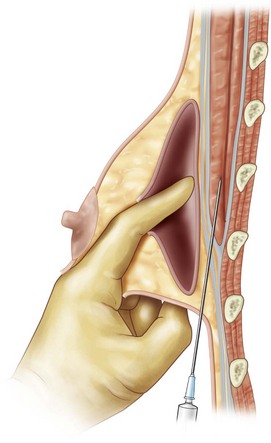

Breast implant replacement

For patients with implants, lipoinjection can be performed simultaneously with implant removal. Breast implants are removed through a periareolar incision, which is placed at the caudal third of the areola margin. The lipoinjection is begun at the deepest layer under the implant capsule and completed with the injection into the most superficial subcutaneous layer. In the deepest layer, the operator takes care to insert and place the needle horizontally (parallel to the body), in order to avoid damaging the pleura and causing a pneumothorax, by inserting the operator’s finger into the implant capsule, placing it on the bottom of the capsule, and recognizing the location of the injection needle (Fig. 26.8). The needle is inserted from the lateral margin of the breast and from the inframammary fold. Injection into the mammary glands or into the capsular cavity is not performed. Finally, the capsular cavity is washed with saline and the periareolar incision is closed.

Preparation procedures of graft materials

Full-CAL

In full-CAL, about twice the volume of lipoaspirate is harvested and half of the adipose portion and all of the fluid portion of the liposuction aspirate are used for isolation of SVF (Fig. 26.1). If a patient has BMI < 25, 1500 ml of aspirated fat tissue can be easily harvested from the abdomen and flanks or thighs. If BMI < 20, fat should be usually taken from both the abdomen and thighs.

Cell isolation procedure (cell processing for SVF isolation)

Processed lipoaspirate cells (PLA) cells and liposuction aspirate fluid (LAF) cells, both are so-called SVF, are separated from the fatty and fluid portions of liposuction aspirates, respectively. Both cells are used for full-CAL, while only LAF cells are used for mini-CAL (Fig. 26.1).

Pitfalls and How to Correct

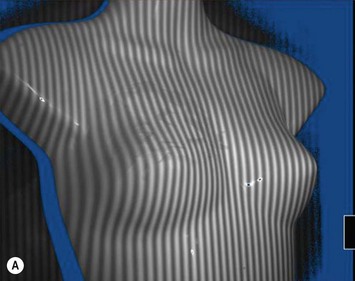

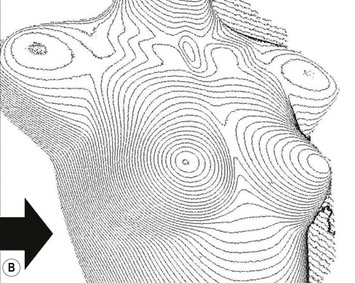

Pre- and postoperative evaluations

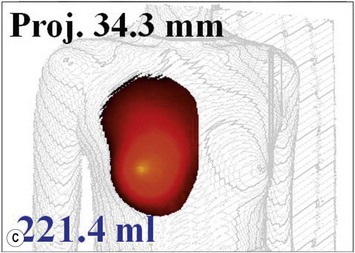

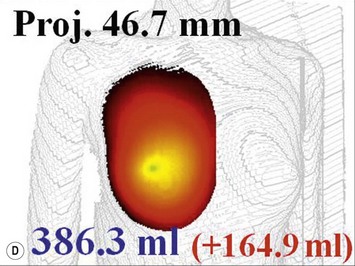

For evaluation of clinical results, physical measurements (maximum and bottom breast circumferences, etc.), mammogram, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, echogram, photograph, and videograph are performed. We have also adopted a three-dimensional measurement system which enables a volumetric evaluation of the breast mound in a standing position (Fig. 26.9). An echogram is easy to perform at each visit and is sensitive enough to detect small cyst formation. Long-term follow up with an annual mammogram is recommended to detect abnormal signs such as calcification.

Clinical results

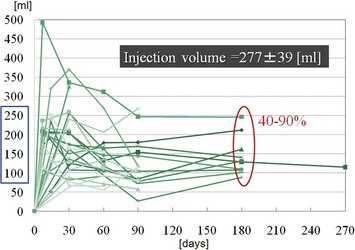

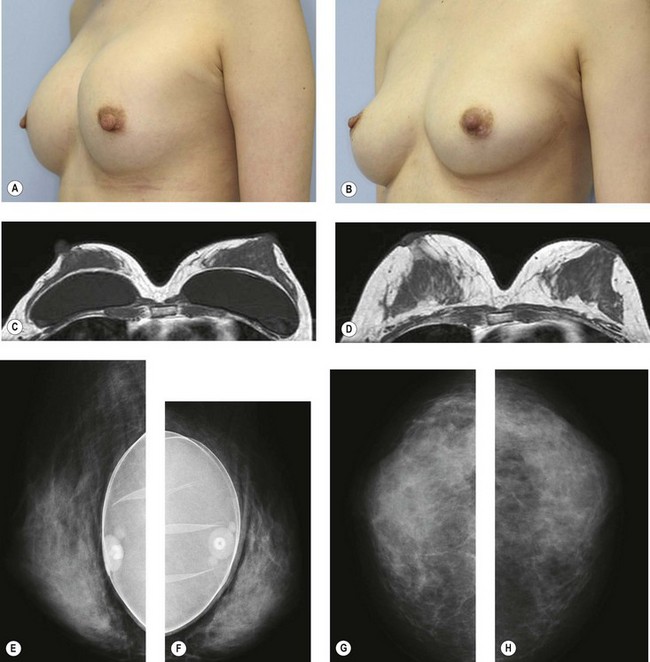

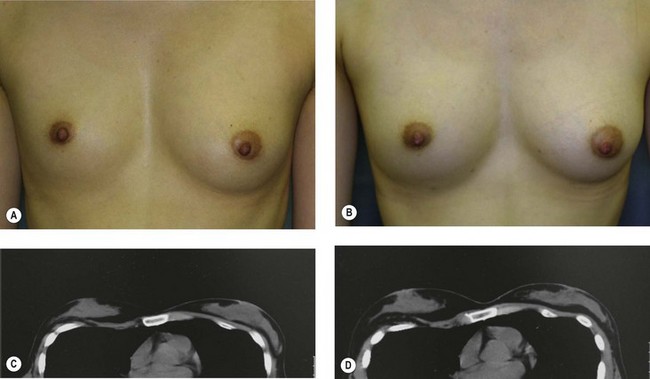

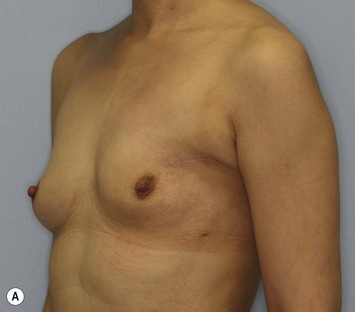

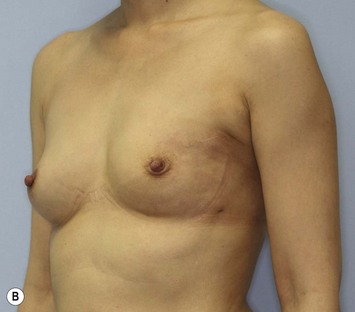

The total operation period is approximately 2–2.5 hours for conventional lipoinjection, 2.5–3 hours for mini-CAL, and 3.5–4 hours for full-CAL. The time of the injection process ranges from 35 to 60 min for both breasts. Subcutaneous bleeding and edema is usually seen on some parts of the breasts, and resolves in 1–2 weeks. Transplanted adipose tissue is gradually absorbed during the first 2 postoperative months (especially during the first month), and the breast volume shows a minimal change thereafter, although skin tension sometimes becomes looser between 2 and 6 months. The three-dimensional measurements showed that the surviving fat volume in full-CAL ranged from 100 to 250 ml at 12 months, meaning that the graft take ranged from approximately 40 to 80% (Fig. 26.10). Compared to breast augmentation with implants of the same size, augmentation with lipoinjection showed a lower height but more natural contour of breasts. Cyst formation depends on the volume and distribution of fat grafts. No cysts are palpable so long as the injection was correctly performed (see below), though cysts with a size of less than 5 mm may be detected by echogram. Patients are generally satisfied with the resulting texture, softness, contour and absence of foreign materials despite the limited size increase possible with autologous tissue. Computerized tomography scans and MRI show that transplanted fat tissue survives well and forms a significantly thick fatty layer, not only subcutaneously on and around the mammary glands but also between the mammary glands and the pectoralis muscles.

Refinement of autologous fat graft techniques

Surviving fat volume varies substantially among patients, and multiple factors are likely to affect the clinical results; patient factors include skin redundancy of the breast and technical factors include devices, graft fat preparation, and injection techniques. It is well accepted that adipose tissue should be placed as small aliquots, preferably within an area 3 mm in diameter. Since it takes a long time to perform the ideally diffuse placement of suctioned fat in breasts,1 we use a disposable syringe with a threaded plunger and connections and a very long needle (150 mm); these devices are critical to performing large-volume lipoinjection safely and precisely in a short time3 (Fig. 26.6). We use a relatively large-sized suction cannula (2.5–3.5 mm inner diameter), centrifuge the aspirated fat, and keep it cooled until transplantation. It should be also noted that aspirated fat tissue should be injected as soon as possible, such as within 60 min after harvest. In our experience, clinical results (increase in breast size) appeared to be superior when centrifuged fat was used compared to non-centrifuged fat. This may be due to the improved adipocyte density and ASC/adipocyte ratio after centrifugation.16 ASC supplementation dramatically improves ASC/adipocyte ratio and is suggested to minimize adipose atrophy after transplantation, though further studies are needed to elucidate the effects of ASC.

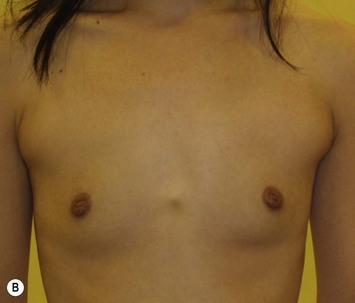

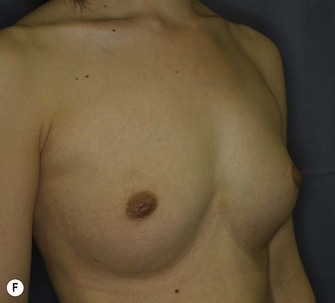

Representative cases

Representative cases are demonstrated in Figs 26.11–26.15; one case from each category (breast augmentation with conventional lipoinjection, breast augmentation with full-CAL, breast implant replacement with full-CAL, inborn breast deformity treated with full-CAL and breast reconstruction with full-CAL).

1 Coleman SR, Saboeiro AP. Fat grafting to the breast revisited: safety and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:775-785.

2 Tuli R, Flynn RA, Brill KL, Sabol JL, Usuki KY, Rosenberg AL. Diagnosis, treatment, and management of breast cancer in previously augmented women. Breast J. 2006;12:343-348.

3 Yoshimura K, Sato K, Aoi N, Kurita M, Hirohi T, Harii K. Cell-assisted lipotransfer (CAL) for cosmetic breast augmentation – supportive use of adipose-derived stem/stromal cells. Aesth Plast Surg. 2008;32:48-55.

4 Matsumoto D, Sato K, Gonda K, et al. Cell-assisted lipotransfer: supportive use of human adipose-derived cells for soft tissue augmentation with lipoinjection. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:3375-3382.

5 Yoshimura K, Sato K, Aoi N, et al. Cell-assisted lipotransfer for facial lipoatrophy: efficacy of clinical use of adipose-derived stem cells. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:1178-1185.

6 Yoshimura K, Shigeura T, Matsumoto D, et al. Characterization of freshly isolated and cultured cells derived from the fatty and fluid portions of liposuction aspirates. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:64-76.

7 Suga H, Matsumoto D, Inoue K, et al. Numerical measurement of viable and non-viable adipocytes and other cellular components in aspirated fat tissue. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:103-114.

8 Zuk PA, Zhu M, Ashjian P, et al. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4279-4295.

9 Strawford A, Antelo F, Christiansen M, Hellerstein MK. Adipose tissue triglyceride turnover, de novo lipogenesis, and cell proliferation in humans measured with 2H2O. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E577-E5888.

10 Spalding KL, Arner E, Westermark PO, et al. Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans. Nature. 2008;453:783-787.

11 Garcia-Olmo D, Garcia-Arranz M, Herreros D, Pascual I, Peiro C, Rodriguez-Montes JA. A phase I clinical trial of the treatment of Crohn’s fistula by adipose mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1416-1423.

12 Fang B, Song Y, Lin Q, et al. Human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells as salvage therapy for treatment of severe refractory acute graft-vs.-host disease in two children. Pediatr Transplant. 2007;11:814-817.

13 Masuda T, Furue M, Matsuda T. Novel strategy for soft tissue augmentation based on transplantation of fragmented omentum and preadipocytes. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:1672-1683.

14 Moseley TA, Zhu M, Hedrick MH. Adipose-derived stem and progenitor cells as fillers in plastic and reconstructive surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3 Suppl):121S-128S.

15 Suga H, Eto H, Shigeura T, et al. FGF-2-induced HGF secretion by adipose-derived stromal cells inhibits post-injury fibrogenesis through a JNK-dependent mechanism. Stem Cells. 2009;27:238-249.

16 Kurita M, Matsumoto D, Shigeura T, et al. Influences of centrifugation on cells and tissues in liposuction aspirates: optimized centrifugation for lipotransfer and cell isolation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1033-1041.