9 Family planning and sexual health

Family planning

The Pearl index

The Pearl index is used to rate the effectiveness of a contraceptive method and is defined as the number of women who will become pregnant if 100 women use that form of contraception properly according to instructions for 1 year (or the percentage of women experiencing an unwanted pregnancy in 1 year of use). This is distinct from the actual failure rate, which is found with ‘typical use’ rather than ‘perfect use’ of the method. Table 9.1 shows the Pearl index for the different contraceptive options.

Table 9.1 Pearl index (the number of unwanted pregnancies per 100 women after 1 year of ‘perfect’ use of the following)

| No contraception | 80–90 |

| Male condom | 2 |

| Female condom | 5 |

| Diaphragm and cap | 4–8 |

| Combined oral contraceptive pill | < 1 |

| Progesterone-only pill | 1 |

| Injectable progestogens | < 1 |

| Progestogen implants | < 1 |

| Contraceptive patch | < 1 |

| Intrauterine contraceptive device | 1–2 |

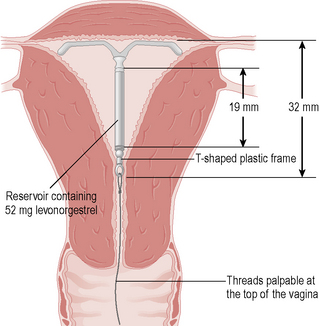

| Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) | < 1 |

| Natural family planning | 2–6 |

| Urinary hormone kit | 6 |

| Female sterilization | 0.5 |

| Male sterilization | 0.05 |

History

The important factors to be considered in the history are:

• Previous contraceptive history and side effects or failures with contraception

• Gynaecological problems: heavy or painful periods, ectopic pregnancy or functional ovarian cysts

• Current or previous STIs and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

• Medical problems: arterial or venous disease, liver disease, diabetes, mechanical heart valves, hypertension

• Current medications: enzyme inducers and some broad-spectrum antibiotics affect the efficacy of contraceptive pills

• Likely compliance with tablets or reliable use of barrier methods

• Need for protection from STIs

• The importance to the woman of not becoming pregnant

• The male partner’s willingness to take responsibility for contraceptive use.

Barrier methods

Hormonal methods

Combined oral contraceptive pill

Types of combined oral contraceptive pill

Different ethinyloestradiol strengths are suitable for different groups:

• Low-strength (20 μg): suitable for women with circulatory risk factors, such as venous thrombosis or arterial disease risks.

• Standard-strength (30 or 35 μg): suitable for most women.

• High-strength (50 μg) (no longer licensed): previously used in obese women, those with breakthrough bleeding or on enzyme-inducing medication.

Thrombosis risk with the combined oral contraceptive pill

The risk of thrombosis is increased by COCP use, but is far less than the risk of thrombosis in pregnancy. The rate of thrombosis per 100 000 women per year is shown in Table 9.2.

Table 9.2 Rate of thrombosis per 100 000 women per year of combined oral contraceptive use

| Previously healthy non-pregnant, non-pill-taking woman | 5 |

| Woman taking second-generation COCP | 15 |

| Woman taking third-generation COCP | 25 |

| Pregnant woman | 60 |

COCP, combined oral contraceptive pill.

Progesterone-only pill

The progesterone-only pill (POP) is also known as the mini-pill.

Injectables and implants

Intrauterine devices

Natural family planning

Time in cycle

Ovulation occurs 12–16 days before a period.

Pain from ovulation and breast changes are less reliable indicators of fertility.

Emergency contraception

Levonorgestrel

This is a progesterone-only regime consisting of 1.5 mg levonorgestrel as a single dose.

Permanent methods

Laparoscopic sterilization

Before arranging sterilization, all women must be informed of the following:

• How the procedure is performed.

• Operative risks: infection, bleeding or visceral damage (bowel, bladder, vessel injury) occurs in 6 in 1000 cases.

• Mini-laparotomy: sterilization by mini-laparotomy if the laparoscopic approach is technically difficult should be agreed to and included on the consent form.

• The lifetime failure rate of 1 in 200 (or two to three pregnancies per 1000 women over 10 years).

• Increased ectopic risk if pregnancy occurs.

• Need for contraception until the next period starts.

• Permanence: the procedure should be viewed as irreversible as reversal is technically difficult, not available on the NHS and has poor success.

• Regret: ask about what the woman would feel if any existing children died or she had a new partner.

• Alternatives: has the woman considered alternative methods? The LNG-IUS is more effective, easily reversible and less invasive. Vasectomy has fewer operative risks and a lower risk of failure.

• There is no effect on periods in the long term – some women report heavier periods, but this probably relates to age and to stopping hormonal contraception.

Contraception in teenagers

• The girl understands the advice, including the implications of having sex and the contraception method.

• He/she has tried to persuade the girl to talk to her parents or other responsible adult about having sex and contraceptive use.

• The girl intends to have sex whether contraception is given or not and, therefore, the risk to her mental or physical health of not giving contraception outweighs the risk of giving contraception.

Barrier contraception should be encouraged, often as well as hormonal, to prevent STI.

Psychosexual medicine

Definitions

Female sexual problems are classified as:

• Loss of desire (hypoactive sexual desire disorder): reduced or absent spontaneous interest in sex with or without difficulty with arousal.

• Poor arousal (impaired sex drive): inability to respond to sexual feelings by becoming physically aroused.

• Anorgasmia: failure to achieve orgasm.

• Dyspareunia: pain with sexual intercourse or stimulation, which may be superficial or deep.

• Vaginismus: involuntary spasm of the muscles of the pelvic floor, triggered by attempted penetration, such that it is difficult or impossible to achieve full penetration.

Aetiology

The aetiology of sexual problems is poorly understood, but psychological and physical factors may be involved. Table 9.3 outlines the main causes.

| Psychological: |

| Stress |

| Life changes |

| Secondary to sexual assault |

| Changes in self-image relating to becoming a mother, hysterectomy, loss of reproductive ability at the menopause or loss of a partner (some increase their sex drive once the concern about becoming pregnant has gone) |

| Physical: |

| Physiological |

| Premenstrual, postnatal or perimenopausal |

| Fatigue |

| Depression |

| Hormonal: |

| Androgen insufficiency, e.g. after TAH and BSO or chemotherapy |

| Hyperprolactinaemia |

| Low oestrogen level means longer to become aroused, vaginal dryness, tiredness, mood changes, less sensitive genitalia and breasts |

| Neurological: |

| Diabetes |

| Multiple sclerosis |

| Cardiovascular: |

| Cardiovascular disease |

| Social: |

| Alcohol excess |

| Drugs: |

| Antiandrogens (cyproterone acetate, GnRH analogues) |

| Antioestrogens (COCP, tamoxifen) |

| Antidepressants (especially tricyclics) |

| Anticonvulsants (especially carbamazepine and phenytoin) |

| Hypertensives |

| Diuretics |

| Anticholinergics |

TAH, total abdominal hysterectomy; BSO, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; GnRH, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone; COCP, combined oral contraceptive pill.

History

Sexual history

Problem

• How long has it been present? Does it relate to time, place or partner?

• Was there an event or trigger for the problem?

• Does it relate to desire for sex, arousal or orgasm, or is there pain superficially or deep during intercourse?

• Does the problem occur just with penetrative sex or also with masturbation?

• For vaginismus and dyspareunia, is the woman able to use tampons and tolerate smear examinations?

• Is there history of recent or former sexual assault or abuse?

Partner

• Is there a current partner? How long has she been with this partner?

• When was the last partner before this one?

• Does she still find her partner attractive?

• Is she worried about him, for example because of his health?

• Are there other relationship difficulties, for example is either partner having an affair?

Medical factors

• Depression and psychotic illness cause loss of desire. Hypothyroidism is associated with low desire and poor arousal.

• Pelvic trauma or operations may interrupt the innervation to the genitalia. Other medical problems such as pain from arthritis or immobility from stroke can interfere with sexual activity.

• Is there vaginal atrophy from postmenopausal hypo-oestrogenization?

Examination

General examination

• Does the woman appear depressed? Is she confident with her body? What is her general mobility? Can she easily reach the couch and bend her legs for examination?

• Look for signs of hyperandrogenism (acne, hirsutism) or thyroid disease and check pulses and blood pressure.

• Check for neurological deficit by examining gross sensation, power and reflexes.

• Perform an abdominal examination for masses or tenderness.

Genital examination

• Check the labia for infection (herpes simplex virus (HSV), HPV) or atrophy. Is the introitus scarred by episiotomy, tears or other vaginal surgery? Is the perineum deficient? Perform a speculum examination for signs of infections such as Candida and bimanual examination for tenderness or masses.

• Vaginismus may be noted as muscle spasm and pain on attempting to insert the speculum or finger for examination.

Management

Individual problems

Impaired sex drive

These women should be screened carefully for medical problems, particularly thyroid disease.

Rape and sexual assault

Management

• Treat any immediate injuries, referring to Accident and Emergency if necessary.

• Perform a full examination to identify any injuries to the head, body or limbs.

• Examine the genitalia for bruises, bleeding, tenderness, tears or foreign bodies.

• Give appropriate contraception – levonorgestrel or the emergency IUCD – after excluding pregnancy.

• Perform an STI screen and repeat after 3 weeks, to allow for incubation periods.

• Consider prophylactic antibiotics for Chlamydia, gonorrhoea and Trichomonas.

• Store serum for virology and repeat the sample for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and hepatitis C after 3 months.

• Depending on the assailant details, give hepatitis B immunoglobulin and initiate an accelerated vaccination course. Postexposure prophylaxis for HIV is indicated in rare situations.

• Encourage reporting of the incident to the police.

• Ensure the woman has a safe place to stay or arrange a place of refuge.

Sexually transmitted infections

History

Investigations

Swabs

Vaginal and cervical swabs:

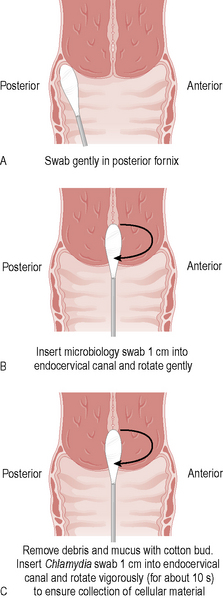

The following ‘triple swabs’ (Fig. 9.2) should all be taken for women suspected of any STI:

1. High vaginal for Candida, Trichomonas and bacterial vaginosis: swab gently in posterior fornix.

2. Endocervical swab for gonorrhoea: insert microbiology swab 1 cm into the endocervical canal and rotate gently to collect cellular material.

3. Endocervical for Chlamydia: swab must be inserted 1 cm into the endocervical canal and vigorously rotated (for about 10 seconds) to ensure cellular material is collected. The collection of discharge on the swab should be avoided by removing secretions first. The swab is transported in a specific medium.

Women who have anal or oral sex should have additional rectal and throat swabs for gonorrhoea.

Chlamydia

Examination may be normal or may show discharge, cervicitis, contact bleeding or adnexal tenderness.

The new national screening programme may help to reduce this risk.

Gonorrhoea

Clinical findings may include discharge, cervicitis, contact bleeding or pelvic tenderness.

However, sensitivity from culture should be checked to be sure the organism is not resistant.

A test of cure should be performed at least 3 days after treatment.

Trichomonas

If metronidazole is ineffective, a single dose of tinidazole 2 grams orally may be used.

Genital warts

• Podophyllin, podophyllotoxin or trichloroacetic acid: local treatments applied in the clinic or at home in cycles

Laryngeal papillomatosis is a very rare neonatal complication of maternal genital warts.

Molluscum contagiosum

There are no symptoms except for cosmetic concerns. Diagnosis is based on the clinical appearance.

Syphilis

Classification

Syphilis is classified according to the timing of presentation and clinical features.

Incidence

The incidence of syphilis is increasing, especially in socially deprived and immigrant groups.

Lumbar puncture and chest X-ray are used for suspected late syphilis.

Tropical genital ulcers

Hepatitis B

Pelvic inflammatory disease

Management

• PID is an infection of the pelvic organs and is generally sexually transmitted. However, the organism is often not identified and may have been asymptomatic in either partner for some time so the diagnosis does not necessarily imply recent infidelity by either partner.

• Her partner(s) will need testing and empirical treatment at a genitourinary clinic (50% will have Chlamydia, 40% gonorrhoea) and she should be provided with a letter for him to take to explain her illness.

• She should not have sex until both she and her partner have completed their courses of treatment because of the risk of reinfection.

• The treatment is prolonged, but symptoms generally improve within a few days of starting treatment.

• She should be seen after treatment has been completed for a full STI screen to exclude any resistant infection.

• There is an increased risk of chronic pelvic pain after PID.

• Ectopic pregnancy is more likely and she should have an early scan (5 weeks) when pregnant, to confirm intrauterine gestation.

• Subfertility is more common after PID (1% tubal infertility after a mild episode and 21% after a severe episode) because of tubal damage, but she should continue to use contraception as most women with treated PID can still become pregnant.

• Barrier contraception will protect her against reinfection.

Criteria for admission for intravenous antibiotics and fluids are:

Other vaginal infections

Candida (thrush)

Bacterial vaginosis

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on Amsell’s criteria, where three of the four following are found:

Summary

• Contraceptive failure is generally user failure rather than method failure and contraceptive teaching is vital to safe and effective use.

• Women requesting sterilization should have clear counselling about complications of the procedure, failure rates, irreversibility, the risk of future ectopic pregnancy and alternative methods of contraception.

• The levonorgestrel-releasing IUD is an effective and reversible alternative to female sterilization.

• Female sexual dysfunction is underreported and women may initially present with an indirect symptom such as dyspareunia.

• Privacy, confidentiality and time are essential for a psychosexual consultation.

• Women who report sexual assault need to have injuries, infection, contraception, counselling and police involvement addressed.

• STIs are increasing and often poorly treated in the gynaecology setting.

• Partner tracing, advice about abstinence during treatment, encouragement of compliance with treatment and follow-up are essential for women with suspected or confirmed STIs.

• A low threshold for antibiotic treatment for suspected PID reduces the long-term complications of chronic pain, ectopic pregnancy and subfertility.