CHAPTER 5 Family Context in Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics

Children’s health and development are a family affair. Whether it involves keeping scheduled appointments for a child’s immunizations, managing feeding difficulties in a child with Down syndrome, or negotiating an adolescent’s desire for autonomy, the daily life of the family is integrally intertwined with the health and well-being of children and adolescents. Family-level factors such as direct and open communication and availability of support have been found to be associated with a host of child health outcomes, including infant mortality,1 lifetime hospitalizations,2 and the likelihood of developing posttraumatic stress symptoms after the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness.3 There are several ways to consider family contributions to children’s development.

First, families are responsible for providing food, shelter, and stability for children. At its most basic level, the provision of basic resources means that the family holds the key to children’s nutritional status and physical comfort. However, families do not always have complete control over available resources; parent’s educational backgrounds, their economic circumstances, and characteristics of the neighborhood also have influences on children’s health.4 Thus, a consideration of family influences on children’s health and development must also include the environments in which families live. Second, families are the holding place for children’s emotional development. Children learn to trust others and regulate their emotions in the safe surroundings of their home before venturing out to school and other social environments. For some children, this is a relatively positive experience, and they come to school well equipped to meet academic and social challenges. For other children, inconsistent and erratic experiences in the home often leave them ill equipped to interact with others, which thus places them at risk for school failure, behavioral problems, and strained peer relationships.5 In all cases, these experiences are mutually influential: Characteristics of the child influence the family, and the family influences the child’s development. Third, family members create practices and hold beliefs that often extend across generations and are influenced by culture. Family life is organized in such a way that it builds on past experiences, which results in predictable routines and imparting of values through recounting personal experience. Many families benefit from their heritages and can use them as guides in meeting the challenges of raising their children. For some families, however, personal histories of neglect, substance abuse, and parental psychopathology interfere with the constructive transfer of generational knowledge and can place children at risk for poor health and development.6–8

The empirical study of family influences on children’s development is complicated at best. Identifying who is in the family; whether to rely on direct observation of family interactions or parent’s report of family climate; how to resolve inconsistencies in reports by mother, father, child, and teacher about child behavior; and adaptation of techniques across cultures9 are just a few of the thorny issues in the scientific study of families. In addition, the changing demography of American families includes increasing numbers of children who are being raised by parents of different ethnic backgrounds, in single-parent households, or in multiple households.10 For the medical clinician, keeping track of all the layers of family life can seem like an overwhelming task, particularly in the short amount of time allocated for patient visits. Rather than ignore the apparent complexity of family life, in this chapter we offer some guidelines for the busy clinician to consider in his or her contact with children and their families. Because the importance of establishing partnerships with families is the cornerstone of pediatric practice,11 a greater understanding of how families operate is in order.

In the past there was a tradition in developmental studies to equate poor child outcomes directly with poor parenting. Such terms as “refrigerator mothers” were coined to suggest that parents (most notably mothers) with cold and harsh parenting techniques were the sole progenitors of their children’s ill health, mentally and physically.12 Childhood schizophrenia was thought to develop from rejecting and harsh parenting styles. Pediatric asthma was thought to arise from overcontrolling and smothering parenting styles.13 At the root of these notions was the assumption that parenting effects were always direct and unidimensional and that neither characteristics of the child nor the surrounding environment had much of an effect on development. Clearly, these notions are outdated because advances in behavior genetics suggest heritability quotients for such conditions as schizophrenia and that symptom severity in asthma is the result of complex interactions among environmental conditions, genetic factors, and family factors.14 The point is that parents do not directly cause their child’s poor health or maladaptive development; rather, children’s health and well-being are embedded in a family context that is subject to a variety of influences, some of which we outline in this chapter.

This chapter is structured in the following ways. First, we provide an overview of a theoretical framework that we believe can be of use for clinicians as they think about the complexities of family life. We first review the social-ecological model originally proposed by Bronfenbrenner.15 This theoretical model is useful in that it allows clinicians to consider not only how the child is situated in the family but also how the family is influenced by the neighborhood in which it lives, the schools that are available to the child, and the culture with which the family most closely identifies. Second, we also consider that children and families change. They do so as part of a process whereby families influence the growth and development of their children and the characteristics of the child also influence how the family functions. This process has been labeled transactional, which suggests that development is characterized by a series of active exchanges between parents and children and that both child and parent contribute to a child’s condition at any given point in time. Thus, we also outline the transactional model as originally proposed by Sameroff and colleagues.16,17 Integrally linked to the social-ecological and transactional perspectives is the role that multiple risk factors play in development. Optimal and poor outcomes are rarely the result of a single factor; rather, the multiple influences of culture, economic resources, family support, and child characteristics cumulatively affect development over time. Thus, we consider the compound effect of environmental risks.

After this strong theoretical grounding in the social-ecological and transactional models and family systems principles, we review some of the literature that illustrates family effects on child health and well-being. Specifically, we examine family factors that promote adjustment in children with a chronic illness, parenting variables that can reduce the risks associated with poverty, and how cultural beliefs and practices enacted in the family context can influence child health and well-being. We conclude with recommendations for clinicians in their clinical decision-making process with families, as well as policy makers responsible for the health and well-being of children. Throughout the chapter, we use vignettes to illustrate our points and to elucidate these complex concepts. Consider the following scenario:

SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL MODEL

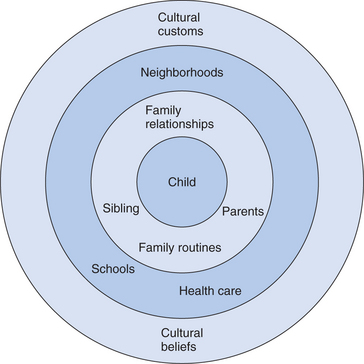

In this brief scenario, we have several elements of Bronfenbrenner’s social-ecological model (Fig. 5-1). The child is at the center of the model. The child’s development is proposed to be influenced by the persons most immediately around him. In this case, Jamie’s development is affected primarily by his mother and siblings. The child’s developmental status is influenced by how responsive his mother is to his needs, as well as by the support and opportunities provided by interactions with his siblings. However, the degree to which the mother is emotionally available to interact with the child in a warm and responsive way may be influenced by her relationship with her ex-husband. We know, for example, that marital conflict can have detrimental effects on children’s development by disrupting effective parenting styles and setting the stage for poor emotion regulation by children.18 Thus, the environment closest to the child’s daily experiences may have a direct influence on his development through exposure to supportive and warm interactions or through a home environment that is characterized by conflict and disruptions. These interactions do not operate in isolation but are influenced by the next level of Bronfenbrenner’s model.

Once we move out of the immediate confines of the family home, we note that there are other influences on child development that can have profound effects on the development of children. This is the level most commonly encountered by pediatricians, inasmuch as how families interact with health care teams also affects how children cope with chronic illnesses.19 In the preceding example, the likelihood that Jamie will develop to his fullest potential will depend not only on his family’s best intentions but also on their ability to gain access to early childhood programs in their neighborhood. Transporting a 4-year-old child five blocks to the home of a babysitter, who must in turn put him on a bus for a long ride for a 3-hour early intervention program, represents a daily challenge. Even under the most optimal home conditions, this would be an added strain to the system that may compromise the child’s developmental progress. Thus, the degree to which the resources available outside the home support, or derail, family investments can have a direct influence on child developmental outcomes.

There is a third level to the social-ecological model that can also influence child development. This layer of the social environment includes such factors as culture, social class, religion, and law. In the preceding example, the legal system has an indirect influence in that public laws guarantee access to public education for all children, regardless of developmental condition. However, as noted previously, gaining access to available education programs can be tempered by resources available in the neighborhood. Culture and religion can also influence child development indirectly. In the case of Jamie, we noted that his mother held strong religious beliefs. Religious beliefs may affect how parents cope with the daily care of children with special needs, so that practices endorsed by mandated programs must also coincide with deeply held doctrines.20

Transactional Model of Development

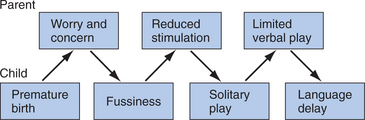

Was the cause of Joanna’s language delay her prematurity and low birth weight? It is known that premature children are at greater risk for developing language delays than are full-term infants.21 Or was the cause of her language delay her fussiness and difficult temperament? Or being less favored than her older brother? Or being left alone? From a transactional perspective, all of these features may come into play when a child’s developmental outcome at any given point in time is considered. In this case, the parents have reasonable concern about their vulnerable infant. Rather than being able to bring their infant directly home, they had to wait and ponder their daughter’s health. Seeking information through the Internet or hospital personnel, they discovered that premature infants are sensitive to light and sound. In this case, Joanna’s fussiness was interpreted by her parents as further indication of her need to have reduced exposure to stimulation, and thus they put her down in the crib frequently. There were fewer opportunities for social interaction and verbal play. This was interpreted as a temperamental difference or perhaps a gender difference in comparison to her brother. Without adequate opportunities for verbal play, Joanna did not develop an age-appropriate vocabulary; thus, her overall language abilities were delayed. This process is outlined in Figure 5-2.

The transactional model as proposed by Sameroff and colleagues16,17,22 emphasizes the mutual effects of parent and caregiver, embedded and regulated by cultural mores. In this model, child outcome is predictable by neither the state of the child alone nor the environment in which he or she is being raised. Rather, it is a result of a series of transactions that evolve over time, with the child responding to and altering the environment. For pediatricians, this model is important because it gives due recognition to the child’s effect on the environment, as well as to the environment’s effect on the child. Pediatricians are frequently faced with situations in which parents feel ill equipped to deal with the challenges of parenting, assuming that childrearing is a one-dimensional task that should conform to a set of prescribed principles easily accessible through a book or the Internet. Typically, this naive view is quickly cast aside with the birth of a second child and parents realize that a one-size-fits-all approach to parenting is rarely successful. Thus, to be able to predict how families influence children, the investigator must also ask how children influence families and how this process develops over time. In addition to recognizing that parents and children mutually influence each other, the transactional model is also important in highlighting the multiply determined nature of risk in family environments.

Multiply Determined Nature of Risk in Family Environments

ADOLESCENT ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT AND PSYCHOLOGICAL ADJUSTMENT

In a large study of adolescents in Philadelphia, the relation between exposure to a variety of risk factors and both academic achievement and psychological adjustment was examined.5 Using an ecological framework, the researchers identified six domains of risk: family process, parent characteristics, family structure, management of community (e.g., social networks), peers, and community (e.g., neighborhood). Adolescents were assigned risk scores for each domain. Lack of autonomy, low-level parent education, single marital status of parents, lack of informal networks, few prosocial peers, and low census tract socioeconomic status are examples of high risk in each of the domains. Increasing numbers of risk factors was associated with large declines in academic performance and psychological adjustment. Using an odds-ratio analysis, the authors compared the likelihood of poor outcomes in high-risk environments with those in low-risk environments. For academic performance, they found that a poor outcome increased from 7% in the low-risk group (three or fewer risk factors) to 45% in the high-risk group (eight or more risk factors)—an odds ratio of 6.7 to 1.

Two factors that are repeatedly identified as contributors to children’s well-being are parental income and marital status. Research on multiple risk factors highlights, in part, how income and marital status are embedded in larger social ecologies that act in concert with other risk and protective factors. This is important in consideration of family effects on child health and development, inasmuch as marital status and economic stability are commonly viewed as structural family variables essential for children’s well-being. Whether a parent is married or holds a prestigious job is not the litmus test for positive family influence on child outcomes. In isolation, these structural variables are not informative about the larger social environment in which the child is being raised or the nature of family process in the home. For example, it is known that there are many types of single-parent families and that children of divorced parents do not necessarily develop mental health problems.23

How children fare during and after divorce is a topic of considerable concern to pediatricians. During the 1990s, more than 1 million children were involved in divorce every year.24 In a meta-analysis of 67 studies conducted between 1990 and 1999, Amato25 found that children of divorced parents scored significantly lower than did children with married parents on measures related to academic achievement, conduct, psychological adjustment, self-concept, and social relations. These differences were less pronounced in African-American children than in white children.26 Marital discord appears to play an important role in how children are affected by parental divorce. Not only the presence or absence of discord but also how conflict unfolds during the dissolution of the marital relationship is important. When children have not been exposed to discord before the divorce, there are more long-term difficulties in adjustment, which suggests that there is an increase in conflict and stress after the divorce.25 In contrast, when there are relatively high levels of conflict before the divorce, dissolution of the marriage can actually be a relief for the child, and there are fewer long-term effects on child adjustment. Thus, what results in poor adjustment in children is not divorce per se but exposure to marital conflict. Experimental studies have also documented that children’s exposure to unresolved marital conflict, in particular, is more likely to result in emotional and behavioral disturbances than are marital disagreements that children witness as reaching some resolution.18

MULTIPLE RISK FACTORS AND POVERTY

Children growing up in poverty are disproportionately affected by chronic health conditions, including asthma, obesity, and diabetes. Children growing up in poverty also show early signs of allostatic load and higher resting blood pressure, which suggests that they are at increased risk for developing other serious chronic health conditions.27 In 2003, the poverty rate was highest for younger children; 20% of children between birth and the age of 5 years of age were being raised in households below the poverty line.28 There are concerns that children exposed to poverty over long periods may be at increased risks for poor physical and social-emotional outcomes. Limited economic resources can have crushing effects on family life, not only through its effects on the provision of basic needs but also by its effects on relationships and parenting. For example, in studies of rural farm families in Iowa, it was found that the downward turn of economic circumstances preceded marital distress and led to increases in hostile and coercive interactions between parents and adolescents.29 As noted previously, the compound effects of risk may influence child outcome; a similar picture holds true with regard to the effects of poverty on child health and well-being.

Evans30 considered the physical and mental health of children raised in poor rural communities and the multiple environmental risks they were exposed to, including crowding, noise, housing problems, family separation, family turmoil, violence, single-parent status, and parent education level. In accordance with the previous reports on multiple risk factors in less economically disadvantaged families, increasing numbers of risk factors were associated with more child psychological distress and feelings of less self-worth. Furthermore, children exposed to more environmental risk factors also evidenced higher systolic blood pressure and elevated neuroendocrine stress reactivity. As Evans stated, “As childhood exposure to cumulative risk increased, overall wear and tear on the body was elevated.” (p. 928).

Risk conditions are often compounded in nature and difficult to unravel. For example, the effects of family poverty on children’s health depend on how long the poverty lasts and the child’s age when the family is poor.31 Single-parent status also cannot be viewed in isolation, because the number of adults in the household has been identified as a marker of socioeconomic status known to be associated with some child outcomes.32 Perhaps one of the multiple-risk contexts that is most difficult to disentangle is that of the overlapping effects of economic conditions and ethnic background. In many empirically based studies of family effects on child development, poverty is confounded with minority status.33 One exception is a study employing the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Bradley and colleagues examined nearly 30,000 home observations of young children diverse in economic and ethnic backgrounds.34 Because of the relatively large sample size, the researchers were able to distinguish between poor and nonpoor European-American, African-American, and Hispanic-American families. In general, they found that poverty accounted for most, but not all, of the differences between the groups with regard to less stimulating home environments (availability of books, having parents read to the child, parent responsiveness). There were some differences, however, that were attributed to ethnic background when poverty status was controlled. For example, European-American mothers were more likely to display overt physical affection during the home observation than were African-American mothers. There were no ethnic group differences in the likelihood that mothers would talk to their infants or answer questions prompted by their elementary school–aged children. Thus, the distinguishing characteristics most often associated with poor outcomes for children, such as the lack of enriching home environments, were more closely associated with low income status than with ethnic background. Further efforts are warranted to separate the effects of poverty from the influence of ethnicity on child outcomes. The long-term effects of coping with discrimination may also affect parenting practices, particularly because these practices are evaluated by researchers within the dominant culture.35 In this regard, it is also important to be cognizant of factors, such as race and economic background of the observer, that can influence evaluations of family process. We return to this point when we discuss family assessment.

FAMILIES AS ORGANIZED SYSTEMS

This is not an unlikely scenario that on the surface appears fairly mundane but may include several elements of healthy family functioning. Families are charged with a host of tasks to insure the health and well-being of their children. Families are responsible for providing structure and care in at least six domains: (1) physical development and health; (2) emotional development and well-being; (3) social development; (4) cognitive development; (5) moral and spiritual development; and (6) cultural and aesthetic development.36 Each of these tasks can be considered as building on the other in a hierarchical manner; however, in day-to-day family life, they often overlap and are not clearly differentiated. In the example just provided, while the family is grabbing a quick breakfast before heading out the door for the day (and, it is hoped, fulfilling the nutritional needs of the children), they are also attending to their cultural and aesthetic development through the arrangement of after-school lessons. Families structure care and meet the developmental needs of their children through organized daily practices, as well as through beliefs that they carry about relationships. We now examine how daily practices, as reflected in family routines, and beliefs, as reflected in family narratives, are related to the health and well-being of developing children.

Family Routines and Healthy Development

In accordance with our focus on the multiply determined nature of child development, children’s health is also considered part of a larger system of family functioning. When we think about family health, we think about what the family, as a group, must do to maintain the well-being of all its members, including establishing waking and sleeping cycles, establishing eating habits, responding to acute illness, coping with chronic illness, preventing disease, and communicating with health professionals. These activities, or practices, are often folded into the family’s daily routines. Pediatricians are poignantly aware that for some chronic health conditions, family involvement in daily care is essential to good health but, at the same time, these management behaviors can be “tedious, repetitive, and invasive” (Fisher and Weihs,37 p. 562). This repetitive nature of management activities sets the stage for creating routines that provide predictability and order to family life. Conversely, the repetitive demands associated with good health care may also disrupt routines already in place and threaten family stability. We first define what we mean by family routines and then examine their relation to child health and well-being.

DEFINING ROUTINES

There is a personalized nature to family routines that makes it somewhat difficult to provide a standard definition. What may be a routine for one family may be absent in another. For example, some families hold very high expectations for when everyone is to be home for dinner and have set rules for the expression of emotional displays, whereas other families have a more laissez faire attitude toward mealtime attendance and rarely remark when someone makes an angry outburst at the table.38 Family routines tend to include some form of instrumental communication so that tasks get done, involve a momentary time commitment, and are repeated over time.39 In terms of normative development, family routines such as dinnertime, weekend activities, and annual celebrations (e.g., birthday celebrations) tend to become more organized and predictable after the early stages of parenting an infant and into preschool and elementary school years.40 The regularity of family routine events such as mealtimes have been found to be associated with reduced risk taking and good mental health in adolescents.41,42 The sense of belonging created during these gatherings has been found to be associated with self-esteem and relational well-being in adolescents and young adults.40,43

HABITS

Habits are repetitive behaviors that individuals perform, often without conscious thought. Behavioral habits are automatic and typically involve a restricted range of behaviors. For example, some children may have developed a habit of snacking while sitting in front of the television set after school. A routine, on the other hand, involves a sequence of steps that are highly ordered.44 For example, a child’s morning routine may include a sequence of having breakfast, brushing teeth, checking the contents of a backpack, and playing catch with the dog before going to school. Healthy (or unhealthy) habits are often embedded in routines. Being in the habit of eating a nutritionally balanced meal may rely, in part, on shopping and cooking routines. For the most part, habits are rarely thought about, and pediatricians must ask repeatedly about parents’ and children’s daily routines to gather accurate information about healthy and unhealthy habits. It is not sufficient to ask whether a child eats a healthy diet, but it may be important to consider whether the diet is offered as part of a regularly organized routine.

Organized family routines may be part of good nutritional habits. For example, parents’ report of the importance of family routines has been found to be associated with children’s milk intake and likelihood of taking vitamins in low-income rural families.45 During the preschool and early school years, if mealtime routines are rushed and interactions are marked by discouragements and conflict, then children are at greater risk for developing obesity.46,47 Furthermore, if mealtime routines are regularly accompanied by television viewing rather than conversation, children consume 5% more of their calories from pizza, salty snacks, and soda and 5% less of their energy intake from fruits, vegetables, and juices than children from families with little or no television use during mealtimes.48 Qualitative studies have noted that individual members can disrupt diabetes management by routinely eating late, regularly serving desserts, and making daily shopping trips to grocery stores that have few choices in the way of fresh fruits and vegetables.49 Grocery shopping routines may also be affected by larger ecologies as lower income neighborhoods are often noted for grocery stores that do not have a full array of fresh produce. Thus, family routines may contribute to children’s health through establishing good nutritional habits and providing regular rather than erratic opportunities to be fed.

ADHERENCE

Adherence to pediatric medical regimens is notoriously poor. According to most surveys, families fail to follow medical advice more than half the time.50 It is unlikely that all cases of medical nonadherence are caused by lack of knowledge or a failure to fully understand doctor’s orders.51 Patients often remark that they fail to follow prescribed orders not because they want to but because they just could not find the time or because other responsibilities got in the way. There is no question that family life is busy and there are multiple demands on everyone’s time. Whether it is juggling home and work, squeezing in one more extracurricular activity, or just trying to get everyone fed during the week, the addition of a medical regimen to family responsibilities can seem overwhelming. One way that some families can adapt to the challenges of medical management is through the organization of their daily routines.

Many treatment guidelines for chronic health conditions suggest folding disease management into daily routines. The management of pediatric asthma is one such condition. Current practice guidelines14 emphasize the importance of daily and regular monitoring of asthma symptoms and detailed action plans in the event of an attack. Many of the recommendations are framed as part of the family’s daily or weekly routines such as vacuuming the house once a week, monthly cleaning of duct systems, and daily monitoring of peak flows. Accordingly, asthma management becomes part of ongoing family life, and families who are more capable of the organization of family routines are expected to have more effective management strategies.

In a survey of 133 families with a child who had asthma, it was found that parents who identified regular routines associated with taking and filling prescriptions had children who took their medications on a more regular basis, both according to parents’ report and according to computerized readings taken on the children’s inhalers.52 Furthermore, when there were regular medication routines in the home, parents had less trouble reminding their children to take their medications, and overall their children rarely or never forgot to take their medications. Because nonadherence to pediatric regimens is quite high53 and parents find themselves in the role of perpetual nagger, the establishment of regular routines may be one way to alleviate distress and promote health in children with chronic conditions. Future research appears warranted in order to consider whether interventions aimed at structuring family routines may positively affect disease management and increase medical adherence.

PARENTAL COMPETENCE

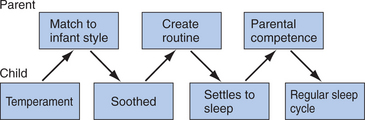

Family routines may also be important in promoting parental competence and establishing caregiving practices associated with children’s health and well-being. There is some evidence to suggest that experience with childcare routines before the birth of the first child is positively related to feelings of parental competence.54 However, in addition to parent skill set, the child contributes to these feelings, as was identified in the transactional model. Infant rhythmicity (e.g., regularity with which infants go to sleep at night) has been found to be associated with regularity of family routines, which, in turn, were associated with parental competence.55 The relation between caregiving competence and family routines during the early stages of parenting is probably the result of a series of transactions. When there is a good match between infant and parent behavioral style, it may be easier to engage the child in family routines. Routines become relatively stable, and the infant is easier to soothe, more amenable to scheduled naps, and less likely to wake in the night. This predictability, in turn, may reduce parental uncertainty and concern and increase feelings of competence. As parents engage in more rewarding daily caregiving activities, they become more confident in their abilities, and the routines themselves become more familiar and easier to carry out; for example, the difference between diapering an infant for the first versus the thousandth time is remarkable. The transactional process of one evolving caregiving routine is presented in Figure 5-3.

BELONGING VERSUS BURDEN

As the family practices its routines over time, individual members come to expect certain events to happen on a regular basis and form memories about these collective gatherings. For some, family is seen as a group that is a source of support, and repeat gatherings are eagerly anticipated. For others, family is seen as a group unworthy of trust, and collective gatherings are avoided. We have found that families who ascribe positive meaning to repeated routine gatherings such as dinnertime, weekends, and special celebrations feel more connected as a group and consider these events as special times rather than times to be endured.39 These feelings of belonging created during family routine gatherings are also associated with the health and well-being of children and adolescents. For example, children with chronic health conditions who report more connections during their family routines are less likely to report anxiety-related symptoms such as worry and somatic complaints.56 Furthermore, adolescents raised in caregiving environments with high-risk characteristics such as parental alcoholism are less likely to develop substance abuse problems and mental health problems when they report a sense of belonging created during family routines.57

In contrast to eagerly anticipating family events are feelings of being burdened and overwhelmed by the daily demands of family life. Feelings of burden can be particularly poignant in caring for a child with a chronic illness. Chronic illnesses can affect family life in notable ways, including added financial burden,58 and can place strains on marital relationships.59

Burden of care specifically associated with daily routine management may be related to quality of life for caregiver and child. In the previously mentioned study of 133 families with asthma, an element of daily care labeled routine burden was identified.52 Routine burden was defined as daily care seen as a chore with little emotional investment in caring for the child with the chronic illness. For both the caregiver and the child, when daily routines were considered more of a burden, quality of life was compromised. Caregivers reported that they were more emotionally bothered by their child’s health condition and their daily activities were affected more when there was more routine burden. Likewise, children reported that they were bothered more by their health symptoms, worried more, and were more frustrated by their health symptoms when their caregivers reported more routine burden. Routine burden was associated with functional disease severity, so that parents of children who required more care also believed that management was a chore. However, even when investigators controlled for disease severity, parents who perceived asthma care as a burden also reported poorer quality of life, as did their children.

CHAOS

It is possible to consider that the absence of routines is expressed as chaos. Chaotic home environments can be characterized by unpredictability, overcrowding, and noisy conditions.60 These types of conditions are more likely to exist in low-income environments and in neighborhoods perceived as dangerous and isolated. Research has indicated that the presence of chaos in the home, rather than poverty alone, mediates the effects of poverty on childhood psychological distress.61 Furthermore, children raised in chaotic environments have more difficulties reading social cues, and their parents use less effective discipline strategies.62 Thus, children exposed to chaotic environments lacking in predictable routines may also be exposed to other risks known to be associated with poor outcomes such as poverty, overcrowding, and dangerous neighborhoods. Again, we emphasize that family factors rarely, if ever, operate in isolation.

SUMMARY

One way to consider families as organized systems is to examine their daily practices. Families are faced with multiple challenges in keeping the group together; they must balance the needs of individuals who differ in age and personality, connect the family to institutions outside the home, and provide some regularity and predictability to daily life. At its most basic level, individuals create daily habits that become parts of the family’s routine practices. These routines are associated with family health in areas such as nutrition, establishment of wake and sleep cycles, and exercise. The establishment and maintenance of routines may enhance adherence to medical regimens. Families who have had experience generating such practices should be better equipped to fold disease management into their daily lives. We return to this point when we discuss models of family intervention useful for pediatricians. The repetition of family routines over time may lead to feelings of efficacy and competence, particularly for parents. Success in caregiving routines may reduce the stresses and uncertainties that accompany being a new parent, which, in turn, may affect children’s well-being in a transactional manner by increasing parents’ sense of personal efficacy. Parents who feel more efficacious are also more likely to interact in positive and sensitive ways that promote child well-being.63

When family routines are repeated over time and family gatherings are anticipated as welcomed events, individual members create memories that include a sense of belonging. This connectedness to the family, as a group, is associated with general health and relational well-being for adolescents and young adults and may reduce some of the mental health risks associated with chronic illness. The converse is also true: If the repetition of family routines over time results in feelings of dread and distance from the group, then there are concomitant effects on the health and well-being of child and parent.

Family Stories of Health and Well-Being

Family stories deal with how the family makes sense of its world, expresses rules of interaction, and creates beliefs about relationships.64 When family members are asked to talk about a personal experience, they must interpret what happened to them in a way that reflects how they work together (or do not), how they ascribe meaning to difficult and challenging situations, and how they relate to the social world. Pediatricians are quite familiar with family narratives, inasmuch as each patient visit presents an opportunity to listen to stories of health as well as illness.65

For families, stories are used to impart values and to socialize children into the mores of the culture. For example, the thematic content of family stories told to children has been found to differ according to whether they are told to girls or boys and whether they are told by mothers or fathers.66 This is important to pediatricians because mothers and fathers recount experiences of illnesses and trauma in different ways, as do boys and girls. For example, after treatment in the emergency department, mothers and daughters are more likely to recall details of the accident in a cohesive and integrated manner than are fathers or sons.67 Thus, pediatricians must consider the source of the narrative, not only the content.

Family stories intersect in the social-ecological model by reflecting cultural values and mores in such a way that the types of stories told differ across societies. For example, European-American and Chinese parents reminisce and tell stories about the past in different ways. European-American parents are more likely to focus on everyday events and to highlight practical problem solving, whereas Chinese parents are more likely to use stories to solve interpersonal conflicts and promote social harmony.68 The point is that the family environment is rich with narratives of personal experience that guide behavior and is influenced by larger social ecologies. We now discuss the key elements of family narratives that may be related to children’s health and well-being.

NARRATIVE COHERENCE

Coherence refers to how well an individual is able to construct and organize a story. Coherence is seen as an integration of different aspects of an experience that provides a sense of unity and purpose and is essential in constructing a personal life story.69 The elements of coherence include being able to tell a story that is succinct and yet including enough details to make it intelligible to the listener, having a logical flow, matching affect with content, and in some instances providing multiple perspectives.70 There has been increasing interest in using personal narratives, or stories, as a means to educate physicians, as well as to connect patients to physicians in the healing process.71,72 Stories that are coherent and well organized are likely to be better understood and easier to incorporate into a therapeutic context than are ones that are disjointed and lack a clear sense of order. The small but burgeoning literature discussed next links the study of family narratives, specifically that of coherence, and health and well-being.

If the coherence of family narratives is to be associated with child outcomes, it must be demonstrated that it varies systematically under high-risk conditions and that it is related to markers of family functioning. There is preliminary evidence that this is the case. Dickstein and colleagues found that parents with major affective disorders such as depression recount family experiences in a less coherent manner and that current depressive symptoms exacerbate this effect.73 There is also evidence to suggest that families who recount experiences associated with chronic illness less coherently also report poorer family functioning overall.74 Furthermore, when the narratives were less coherent, families had more difficulty engaging with the interviewer. Why might these findings be important for children and for pediatricians? First, consider their potential link to children’s outcomes.

There is a relatively strong empirical base linking coherence of narratives told about attachment relationships and the mental health and well-being of children, adolescents, and young adults.75,76 When parents and children are able to create coherent accounts of their caregiving relationships, they tend to be secure in their attachments and mentally healthy in the long run. A similar pattern is emerging in the case of family relationships. When individuals talk about family relationships in a coherent manner, family functioning appears to be more well regulated, providing a potentially more supportive environment for children. Why might these findings be important for pediatricians? During the course of a routine patient visit, families present a wealth of information, often in narrative, or story form. Families who have difficulties getting their points across to the pediatrician and creating a coherent account of personal events may be presenting similar images to their children. We have been particularly struck by the relation between coherence and family problem solving. Families who have difficulties engaging with interviewers and creating coherent accounts of chronic illness also express difficulties in family problem solving and communication.74 This combination may present added risks for children, who rely on their parents for clear and direct communication and effective problem solving. A cautionary note: This is a nascent line of research, and we also recognize that a transactional process is probably in place in which health care professionals probably influence the types and forms of information that families are willing to communicate.77 We also recognize that reliably detecting the relative coherence of a family narrative is beyond the reach of routine pediatric practice. Most systems for evaluating narrative coherence are fairly complex and involve lengthy training.78,79 Furthermore, it is not clear whether the stresses associated with a doctor’s visit may affect coherence in ways unrelated to psychological functioning.

RELATIONSHIP BELIEFS

Families create beliefs about relationships that vary along the dimension of trust, reliability, and safety.70 Relationships can be seen as sources of reward and worthy of trust or viewed as potential sources of harm and unreliable. Family narratives frequently depict the degree to which relationships are seen as something that can be mastered and rewarding or as overwhelming and confusing. In the case of the latter, statements are often made that reflect dissatisfaction and disappointment in relationships. Also, statements are made whereby relationships are seen as opportunities for experiencing appreciation and pleasure. As families are built around mutuality in relationships, the degree to which they are satisfactory and rewarding should bear concordance with children’s health and well-being.

Just as there are different conditions in which narrative coherence systematically varied, there are distinctions among family narratives about relationships in relation to children’s outcomes. Two types of outcomes are particularly pertinent for pediatricians: children’s behavior problems and health care utilization. There have been a few studies that have linked depictions of family relationships in stories to children’s behavior problems. Parents who recount family experiences as including rejecting and unrewarding relationships tend to have children with more problematic behaviors according to self-report measures.80 Furthermore, when parents tell stories that include depictions of family relationships that are unreliable and unsatisfactory, there are increased levels of negative affect when the family is gathered as a whole during routine mealtimes.73,80 Children’s stories of family experiences reflect a similar pattern. Children who have experienced abuse and neglect depict family relationships as less rewarding in stories about family events.81,82 Interestingly, children enrolled in an attachment-based therapeutic intervention changed their representations of family relationships, depicting caregivers as more trustworthy in the narratives after intervention than did children in the comparison group.82 Thus, the portrayal of relationships in family narratives reflects parents and children’s interpretation of the trustworthiness of others, which, in turn, may be related to social interaction and the regulation of behavior.75 There is also some evidence that narratives hold promise in understanding how families utilize health care services.

When asked to talk about the effects of an illness on daily life, family members typically have little trouble generating a story. However, there is no single way in which families meet the challenge of organizing their lives or responding to normative or nonnormative events, as already noted. The same holds true in considering how families recount strategies of care revealed in narratives. Families can rally around the care of an individual in a variety of ways.83 For some families, everyone is involved, and there is a team-based strategy so that multiple members of the family are “on the lookout” for the identified patient. This may mean being available to pick up prescriptions from the pharmacist, translating doctor’s orders into a native language, or reading a book out loud when a sibling does not feel well. For other families, there is one expert in the family who takes charge whenever someone is ill or whenever there is a chronic health condition. Sometimes this person takes on the role across generations, so that he or she is responsible for the care not only of offspring but also of older parents. In a third type of family management style, few roles are assigned, and there is little planning around emergencies and crises. Typically in these families, anxiety calls the family to action. These management strategies can be depicted in narratives and reflect beliefs about family relationships. In the first case, team-based strategies revolve around assumptions that family relationships are reliable and multiple members of the family can be called on at a moment’s notice. In the second case, relationships in general may be rewarding, but roles are assigned in such a way that there is a clear leader and authority in the family. In the third case, either relationships are seen as a bother and unreliable, or worry and anxiety predominate to the extent that relationships are precarious. When interviews about coping with a chronic illness were categorized by these management strategies, it was found that families that use either the family partnership or the expert-based approach were more likely to adhere to the prescribed medical regimen than were those who used more anxiety-based coping strategies.83 Furthermore, families that depicted their management strategies in the interviews as more reactive and relationships as less satisfactory were more likely to use the emergency room for care 1 year after the interview.

SUMMARY

Thus far, we have considered the family as an organized system that maintains itself as a group through organized routines and reaffirms its beliefs about the importance of relationships through accounts of personal experiences. These are family-level processes that come to form the family code. The family code is created to regulate child development, extending across generations, and involves the coordinated efforts of two or more people.17 Embedded within the family code are parent-child interaction patterns that can facilitate the smooth operation of daily life, as well as foster achievement of developmental tasks. We now briefly review some of the essential ingredients of family interaction that serve to support healthy development.

Family Interaction and Healthy Development

Family interaction can be evaluated along a variety of dimensions. Some of the more common domains are warmth, control, support, communication, problem solving, criticism, and affect.84 In this snippet of a mealtime observation, the family balances the need to maintain the group as a whole with expressions of independence. For most families, this balance is struck relatively effortlessly with good humor and warmth. A chorus of “Happy Birthday to You” to the grandmother, even in her absence, does not disrupt the flow of the meal, and individual desires are respected. In other families, however, expressions of autonomy may be met with harsh control, and negative affect predominates. Considerable effort has been directed toward identifying patterns of interaction associated with more optimal outcomes for children with chronic illness and children at risk for developing health problems.

Children with a chronic illness are at greater risk than children without a chronic illness for developing behavior problems or a psychiatric disorder, such as depression or anxiety. In fact, epidemiological surveys have revealed that children with a chronic illness are twice as likely to develop a diagnosable behavioral or psychiatric disorder.85 The causal mechanism for why children with a chronic illness are more at risk than their healthy counterparts is not known. Early speculations suggested that certain patterns of family interaction were more prevalent in families with a chronic illness and that these interaction patterns led to and sustained the disease state.86 On the basis primarily of clinical observations, the most common pattern was considered to consist of parental overinvolvement, overprotection, poor conflict resolution, and a primary focus on the child with the illness to the neglect of the marriage and other family members’ needs. This pattern has not been borne out in the empirical literature and fails to take into account the shifting nature of illness and its effect on family dynamics.87

Researchers have begun to examine how family interaction patterns may be part of a transactional process between characteristics of the child, health status, and caregiving. Researchers theorize that children may have a limited range of cognitive or emotional skills for coping with their disease or that the increase of environmental stressors, such as medication regimens and missed school days, may contribute to adjustment difficulties.88,89 The increase of disease-specific responsibilities places greater burden on the family as a whole, with the potential risk for increased conflict among family members and impaired levels of family functioning. A child may resent such conflict or family changes and externalize his or her resentment in the form of behavioral problems.89

Family conflict, observed either directly or through self-report, appears to disrupt effective disease management strategies and to adversely affect child health and well-being. Highly conflict-ridden family relationships can compromise communication, supervision, and division of responsibilities.90 It is likely that family conflict affects child outcomes through alterations in daily health practices, inasmuch as poor adherence to medical regimens has been found to be associated with family conflict.91,92 Furthermore, family conflict has been associated with poor glycemic control in children with diabetes.93 Family conflict may also be an indicator that the family as a group has not been able to adjust to the child’s illness, which in turn can lead to emotional distress for parent and child alike.94 Whereas the research linking family conflict and children’s health under chronic conditions appears to be mediated by disruptions in medical adherence, other investigators have examined how exposure to family conflict may result in compromised health by reducing children’s ability to respond to stress.

In summarizing the literature on high-risk family environments, Repetti and colleagues27 reported that family conflict is associated with higher rates of reported physical symptoms and lower attainment of developmentally expected weights and heights. They suggested that family conflict may lead to increased stress reactivity and allostatic load in children in high-risk environments. This argument is consistent with the research that we reviewed on multiple risk factor effects under poverty conditions. Indeed, the profile of extensive conflict, poor emotional and social support, and children’s heightened stress reactivity is consonant with the multidetermined model outlined previously. Thus, lower levels of family conflict may be one more element in the larger picture of family health.

Family conflict has received the most attention in the empirical literature perhaps because it is relatively easy to identify from video recordings. It may also be the case that negative interactions have a more toxic effect and that a modest amount of negativity can lead to poorer outcomes. According to family systems principles, there are other aspects of family interaction that should also contribute to healthy family functioning. These include direct and clear forms of communication, effective problem solving, responding to the emotional needs of others, showing genuine concern about the activities and interests of others, and supporting autonomy.95 To date, most researchers have reported on the overall general functioning of the family as it relates to child and family adjustment to such conditions as pediatric cancer,96 maternal depression,7 cystic fibrosis,97 and asthma.98 There is some evidence to suggest, however, that effective problem solving and direct forms of communication are associated with healthier outcomes for children with chronic illnesses. For example, adherence to dietary restrictions for children with cystic fibrosis is related to more positive forms of communication and problem solving observed directly during mealtime interactions and during structured laboratory interaction tasks.99,100 A similar pattern has been noted for families and children with diabetes.101,102

CULTURAL VARIATIONS IN FAMILY CONTEXT

Cultures, in general, are organized around a set of principles that guide individuals’ behavior in such a way that they are consistent with the mores of the larger society. Cultures vary in terms of the relative values given to individual strivings for autonomy and independence versus placing the needs of the group before the needs of the individual.103 In relation to these values of individualism and collectivism, there are variations in terms of deference to authority and what “counts” as a personal transgression. In some cultures, for example, a child is more likely to get into trouble or be disciplined for something that would cause shame to the family; in other cultures, punishment is doled out for not understanding how personal actions reflect flaws in an individual’s character.104 This point is important for pediatricians, because issues of discipline and parental control are embedded in both a cultural and a family context.

These values are transmitted, in part, through the organization of daily family life. The study of everyday tasks and situations is not only embedded in culture but is also at the very heart of how behavior is shaped by society.105,106 By focusing on how families in different cultures carry out daily routines such as household chores, investigators are able to get a glimpse at what is culturally relevant and how roles are assigned to facilitate socialization. Thus, we consider how the practice of family routines in different cultural contexts is related to children’s health and well-being.

When investigators consider cultural variations, they are also interested in situations in which there is a mismatch between the predominant society and families or between parents and children. A mismatch in values presents an added tension for individuals and family members, potentially compromising health and well-being. One such situation is a mismatch of values between generations during the process of immigration. A breakdown or deterioration of routines and rituals may indicate difficulties making the transition from one culture to another. Replacing old rituals with new ones, on the other hand, may also be an indication of adaptation to a new cultural environment. This is not an “either-or” process, inasmuch as current conceptualizations of the acculturation process suggest that there are family-level advantages to retaining connections to the country of origin, as well as incorporating aspects, such as language, of the newly adopted country into everyday practices.107,108

Recent census data document that 20% of children in the United States have immigrant parents and that 25% of children in low-income families are of immigrant status (www.census.gov). With immigration comes a blending of beliefs that regulates family interactions with health care professionals, as well as with each other. Therefore, we also consider briefly how cultural beliefs interface with family process and influence children’s health and well-being. It is beyond the scope of this chapter to cover the multitude of ways that culture and family processes transact to affect children’s development. Thus, we structure our discussion around three topics: family routine practices in Latino families, beliefs about autonomy in immigrant Chinese families, and disease management strategies in African American families. Although these may appear as disjointed topics, we have selected them to highlight how cultural values intersect with domains of family life that we have previously discussed.

Variations in Family Practices: Mealtime Routines in Latino Families

Here we see two approaches to feeding a toddler that may be rooted in cultural values of what is considered good conduct. Latino and Anglo individuals have been described as differing in the extent to which they hold values and meaning systems that are congruent with sociocentrism or individualism.109–111 Sociocentrism refers to an emphasis on the relationship between the individual and the group and subordination of ones personal interest to that of the group, resulting in a construction of the self as fundamentally linked to others. Latino cultures have typically been identified in the research literature as sociocentric.103 Within many Latino cultures, sociocentrism may be made evident through the importance placed on respect (respeto) and dignity (dignidad) in personal conduct. Both qualities are essential in the development of proper demeanor: knowing the level of decorum and courtesy that is required in a given situation.112 With regard to child rearing, this does not necessarily mean that Latino parents want their children to always do what is best for the group at the expense of their own happiness; rather, it is through genuine care and not malcriado (being poorly brought up) that a person can bring respect and happiness to the family and to himself or herself. Traditional Puerto Rican culture, for example, has been described as emphasizing interpersonal obligations, personal dignity, and respect for others.113 Puerto Rican mothers may believe that qualities such as malcriado and a lack of dignidad and respeto will give rise to a lack of acceptance from others in the community, which will reflect poorly on the family and the child, eventually leading to unhappiness for the child. In sum, the goal in traditional Latino cultures is to raise a child to become una persona de provecho—a person who is worthy of trust and is useful to the community.112

Harwood and Miller110 found that Anglo mothers were more likely than Puerto Rican mothers to stress the importance of an infant’s ability to cope autonomously with the stress of being left alone. In a series of studies, Harwood and Miller examined Anglo and Puerto Rican mothers’ preferences for behavior in their children. Puerto Rican mothers were more concerned about their children’s ability to maintain proper respect and dignity and were more likely to focus on their children’s ability to remain calm and good-natured, and to be physically close with their mothers, whereas Anglo mothers reported that they preferred infants who were able to manage autonomously.110 In a follow-up study, Harwood109 interviewed mothers about what they valued in children and found evidence that Anglo mothers placed greater importance on personal development and self-control. Harwood’s studies provide evidence for the existence of culturally defined values in the meanings that mothers may give to child behavior. Specifically, Anglo mothers placed more importance on personal competencies, and Puerto Rican mothers placed more importance on whether the infants were able to maintain proper demeanor and physical closeness.109

These beliefs and values may be expressed in the practice of mealtime routines. Latina (specifically Puerto Rican) mothers were less likely then Anglo mothers to encourage their children to feed themselves.111 In addition, the strategies that parents used to teach their children to feed themselves differed. Latina mothers were more likely to guide their children in getting food from the plate into the mouth and/or holding their children in their lap while they ate, rather than seat them in a high chair. Although these are relatively simple examples, they highlight how repetitive socialization practices are embedded in cultural values. How might pediatricians encounter the effects of these cultural practices and belief systems? One way is through the parents’ tolerance for and understanding of disruptive behaviors.

Families socialize their children in accordance with the values held by the culture as to what is acceptable and unacceptable behavior. As noted, in some Latino cultures, there are values held for self-control and personal demeanor that reflect the family’s stature. In interviews of Latina mothers whose children were seen by professionals for disruptive behaviors, three personality characteristics of the children were identified as salient: inteligente, malcriado, and de carácter fuerte.114 Children who were referred for disruptive behaviors by their teachers were seen as intelligent (inteligente) by their mothers, which suggests that misbehavior must be the result of giftedness or clever mischief. One half of the mothers interviewed mentioned their children’s bad manners (malcriado); however, of those who alluded to their children’s rude conduct, some did so as a means to disconfirm the trait and expressed concern that others would think of their child as spoiled. Mothers also described their children as possessing a willful temperament (de carácter fuerte). In contrast to malcriado, de carácter fuerte is seen as something that can be ultimately controlled, although not permanently altered. Together, this triad of characteristics provides the parents with an explanatory set of beliefs to account for disruptive behaviors that are inconsistent with the cultural values of good conduct.

Just as a cultural perspective may affect how misbehavior is understood, it can also affect how developmental milestones are interpreted. In consideration of whether a child is disabled or capable of performing the routine activities of daily living, it is also important to consider the degree to which the family and culture supports independence and autonomy. There may be significant cultural variations in the expected norms of activities of daily living for children with disabilities. For example, Latino parents, caregivers, teachers, and therapists expect children with disabilities to be dependent on their parents for many daily skills until much later than would be expected on tests with norms for white U.S. mainland residents.115 This pattern holds true for their nondisabled peers and is attributed to the interdependence between parents and children and cultural values of anonar (pampering or nurturing) and sobre protective (overprotectiveness). Thus, parents may report the achievement of developmental milestones at a rate that would be cause for concern by the pediatrician and yet are within a range considered normative in a given culture.

Immigration and the Balance of Family Obligations

The unanswered question to this scenario is whether Susan is relatively happy or distressed by not spending time with her peers. For native-born American teenagers, spending time with peers is considered part of the natural progression of moving out of the home and becoming more autonomous. For some adolescents of immigrant families, however, staying close to home is considered part of being a good son or daughter. Whether this causes distress may depend on the relationship between parent and adolescent and beliefs that the adolescent holds about family obligations. Chinese adolescents report, on average, two family obligation activities per day and spend slightly more than one hour each day assisting and being with their families.116 Overall, girls spend more time and carry out more family obligations than do boys. Socializing with peers is negatively related to family obligations on any given day. However, the amount of time spent in family obligations does not necessarily lead to greater conflict or personal distress for these adolescents. These youths appear to expect to balance family and social obligations and make deliberate decisions to spend time with their families. Rather than leading to a sense of alienation from peers, these daily practices may reinforce cultural beliefs and provide a sense of identity. “Family obligations may provide the children from immigrant families with a sense of identity and purpose in an American society that, at times, has been accused of emphasizing individualism at the cost of heightened adolescent alienation” (Fuligini et al,116 p. 311). Thus, obligation to the family is balanced with spending time with peers and does not necessarily create personal distress. Yet to be answered, however, is whether this balanced perspective weakens with subsequent generations as extended engagement with popular culture may create increased opportunities to weigh obligations to peers over those to parents.

Ethnic Variations in Family Management Practices

A first step in considering how parents transfer responsibility of management practices is to identify beliefs that the family may hold about the condition that may act as a barrier to good health. In interviews with African-American parents of children with asthma, it was found that a more holistic approach to managing asthma that included both the child’s mental and physical well-being was desirable.117 Many parents reported that they modified the physician’s treatment plan to include nonmedicinal alternatives for their children’s symptoms and held strong personal beliefs against the use of medications. Thus, when it is time to transfer the responsibility of disease management to children, clinicians must consider how beliefs about medication are also being parlayed.

An additional point to consider is that transfer of responsibility may not necessarily be from one caregiver to the child, inasmuch as two or more caregivers are frequently involved in disease management in urban and African-American families.118 Having multiple family members involved in asthma care extends into the patient’s adolescent years.119 Multiple family members and extended kin networks can serve as sources of support. It is also important, however, to carefully consider whether availability of support translates into clear assignment of responsibility. In interviews with adolescents and their parents, Walders and colleagues found that African-American parents overestimated the amount of responsibility that adolescents were taking for their asthma care.119 As the authors pointed out, the wide array of family structures can be simultaneously a source of support and a source of confusion when it comes to assigning responsibility. Pediatricians are in the unique position to address transfer of responsibility with their patients over time while being sensitive to how variations in family structure and cultural beliefs may regulate this process.

Summary

Although there is little disagreement that changes in population demographics mandates broader conceptualizations of cultural influences on health,120 the empirical base linking cultural variations in family practices and children’s health is somewhat limited. There is a growing literature that documents cultural and ethnic variations in family routines and beliefs associated with child outcomes. It is important to emphasize that there is considerable heterogeneity within a given culture and that we have made only generalizations. Furthermore, the effects of economic stability and resources on immigration cannot be ignored and in all likelihood play a significant role in the understanding of how cultural variations in family context contribute to children’s health.121,122

FAMILY-BASED INTERVENTIONS

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to provide a comprehensive review of all the intervention programs available to families. The interested reader is referred to reviews and collected volumes for more thorough discussions of the topic.123–127 There is growing empirical evidence that targeting the whole family as a method of treatment for disease-specific issues is effective. For example, in intervention studies aimed at improving disease management in insulin-dependent diabetes, families who participated in Behavioral Family Systems Therapy, in comparison with families who received educational forms of intervention, showed higher rates of improvement in parent-adolescent relations and lower rates of diabetes-specific conflict.128 In a review of interventions for survivors of childhood cancer and their families, Kazak and associates129 summarized empirical evidence for interventions from four categories specific to pediatric oncology: understanding procedural pain, realizing long-term consequences, appreciating distress at diagnosis and over time, and recognizing the importance of social relationships. Kazak and associates pointed to the importance of developing interventions that target families on the basis of a particular set of risk factors, of designing more empirical interventions for families experiencing disease relapse, and of striving to develop interventions that are effective for ethnically diverse families. Current thinking in family-based interventions for pediatric conditions is that a one-size-fits-all strategy is unlikely to be effective.130 Because families are developmentally complex systems that routinely undergo change, as we have outlined, it is unreasonable to expect that a uniform strategy aimed at altering family level behaviors would be advantageous across all families and all situations. Thus, in this section, we consider several approaches that may be appropriate for families at a given time. We place these strategies in the transactional model previously discussed. Using a decision tree, we outline different strategies that can be implemented by drawing on the existing strengths and resources of the family and tied into previously established forms of intervention such as interaction guidance, behavior management, and relationship building techniques.

Transactional Model of Intervention

In this scenario, we see a transaction unfolding in which the child’s symptoms have disrupted the daily routines of family life. According to the principles of the transactional model, behavior can change at multiple points, whereby the child’s condition affects the organization of the family and the family’s behavior affects the well-being of the child. Interventions that capitalize on the strengths of the system at a given time and minimize the need to alter the system as a whole—a timely and expensive endeavor—can be targeted. Sameroff131 proposed that there are at least three categories of intervention that can be implemented to effect change in either the child or parent: remediation, redefinition, and reeducation. Remediation efforts are aimed at changing the way the child behaves toward the parent. For example, providing Louisa with a controller medication should reduce her symptoms, which, in turn, should reduce her mother’s worry about her condition. Redefinition changes the way the parent interprets the child’s behavior. In Louisa’s case, interventions aimed at helping her family understand her respiratory symptoms as part of a chronic illness rather than a recurring cold may change the ways in which they respond to her symptoms. Reeducation efforts are aimed at changing the way the parent acts with the child through increased knowledge. In the case of Louisa, education efforts aimed at following an action plan and reducing exposure to environmental toxins would reduce Louisa’s symptoms. To these three Rs of intervention, Fiese and Wamboldt132 added a fourth type of intervention often warranted in health care settings: realignment. Realignment is called for when family members disagree about a course of action and daily practices have been disrupted to the extent that the health and well-being of the child are compromised. In Louisa’s case, if the parents disagreed on her diagnosis of asthma, then there would be serious consequences as to whether they would agree on a plan of action if she had another asthma attack. These four Rs of intervention are now examined in the framework of family routines and a clinical decision-making process that is accessible to pediatricians.

CLINICAL DECISION MAKING APPLIED TO MEDICAL ADHERENCE

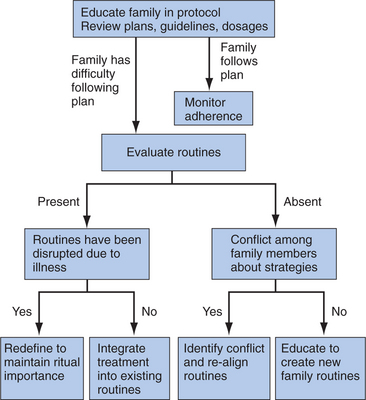

We have already discussed the roles that family routines and daily practices may play in the health and well-being of children. We now incorporate these practices into the clinical decision-making process as a guide for pediatricians when working with families who are expected to follow a daily treatment protocol to maintain the health and well-being of their children. We chart this process as part of a decision tree, although we also recognize that there are instances in which family circumstances warrant more than one type of intervention (Fig. 5-4).

The second alternative in evaluating routines is cases in which families do not have routines in place. In these situations, it is important to consider whether there is conflict among family members about strategies for implementing treatment recommendations. As previously noted, conflict can have a detrimental effect on children’s health. Family members can also disagree about the relative value of particular disease management routines and the relative importance of attending to specific aspects of an individual’s prescribed protocol. We noted, for example, in families with a diabetic member that routinely eating late or serving sweet desserts can counteract the individual’s good intentions. It is important to identify the source of conflict around implementing the routine. Sometimes these conflicts can be rooted in myths and misperceptions about the prescribed protocol: for example, not wanting to take daily prescribed medications for fear that the child will become “hooked on other drugs.” There are other instances in which there are disagreements that are rooted in marital conflicts. Under these circumstances, it is important to separate marital conflict and discord from managing daily routines. This is particularly germane in the case of divorced and separated families in which children are living in two households and there may be two sets of rules and routines. It is important to come to an agreement about consistency in routines (e.g., bedtime, mealtime, medication use) so that the child is protected from the harmful effects of conflictive households.