Chapter 28 Family and Intimate Partner Violence, and Sexual Assault

Intimate Partner Violence and Family Violence

Intimate Partner Violence and Family Violence

Family violence refers to abuse of children and older individuals in addition to violent behavior directed against a current or former intimate partner. Intimate partner violence (formerly known as domestic violence) is defined as intentionally abusive or controlling behavior by a person who is in an intimate or close relationship with the victim.

The focus of the first part of this chapter is on intimate partner violence because the obstetrician-gynecologist is most likely to deal with the effects of abusive behavior directed against an intimate domestic partner. Intimate partner violence can include verbal abuse, intimidation, social isolation, and physical assault, such as a punch, a kick, a threat, a severe beating, an act of sexual assault, or even murder. It occurs in every age group, in all ethnic groups, in every occupation, and in every socioeconomic group. Although the obstetrician-gynecologist may be called to see a patient with acute injuries from partner violence or sexual assault, he or she is more likely to have to deal with the nonacute clinical manifestations of abuse (Box 28-1). Although most often perpetrated by a man against a woman, the gender relationship may occasionally be reversed. Intimate partner violence can also occur between same-sex partners.

BOX 28-1 Clinical Manifestations of Possible Intimate Partner Violence∗

Data from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG): Special Issues in Women’s Health-Intimate Partner and Domestic Violence. Washington, DC, ACOG, 2005.

ADVERSE EFFECTS OF INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE

Social services for women who are victims of intimate partner abuse are inadequate. Nearly one third of battered women who request refuge are turned away because of a lack of space. Those turned away and their children often must return to a violent home. Many become homeless and involved in substance abuse as an escape mechanism or because they are forced into use and addiction by their partners.

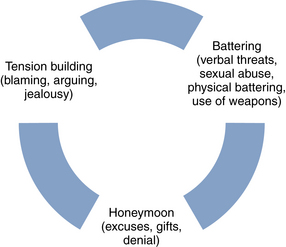

The abuser often provides for and is periodically in a caring and loving relationship with the victim, who may still love the abuser despite the abuse. Other obstacles to leaving the abuser include (1) fear of more abuse, (2) loss of economic support, (3) fear of social isolation, (4) feelings of failure, (5) promises of change, (6) previously unanswered calls for help, and in many cases (7) fear of loss of child custody. Figure 28-1 illustrates the cycle of violence that exists in these abnormal relationships.

ADDRESSING INTIMATE PARTNER AND FAMILY VIOLENCE

In addition to the need to comply with any reporting requirements (some states mandate reporting to appropriate authorities if there are acute injuries), social workers and other professionals should always be consulted when abuse is acknowledged, or even if it is just suspected. Box 28-2 lists the responsibilities that health-care providers have in addressing intimate partner and domestic violence.

Sexual Assault and Rape

Sexual Assault and Rape

MEDICAL CARE FOR SEXUAL ASSAULT

Prophylaxis is suggested as preventive therapy. This includes hepatitis B vaccination (if previously unvaccinated) and appropriate antibiotics for sexually transmitted infections (see Chapter 22). It is critical to provide any woman at risk for pregnancy with emergency contraception (see Chapter 26). If prophylaxis for HIV is considered necessary, consultation with an HIV specialist is recommended. Tetanus toxoid should be administered to an unprotected, injured woman.

PSYCHOLOGICAL SEQUELAE OF SEXUAL ASSAULT

AFTERCARE PLANNING

Before discharging the patient, it is important to ensure that she has a safe place to go and a suitable means of transportation. She should also be given (in writing) the names, addresses, and phone numbers of resources available in the community to meet her medical, legal, and psychosocial needs related to the assault (Box 28-3).

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Special Issues in Women’s Health: Intimate Partner and Domestic Violence. Washington DC: ACOG; 2005.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Special Issues in Women’s Health: Sexual Assault. Washington DC: ACOG; 2005.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Intimate partner violence prevention. Retrieved April 12, 2008, from http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/dvp/IPV/default.htm.

Ellsberg M., Jansen Ha, Heise L., et al. for the WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women Study Team: Intimate partner violence and women’s physical and mental health in the WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence: An observational study. Lancet. 2008;371:1165-1172.

Karch D.L., Lubell K.M., Friday J., et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) surveillance for violent deaths. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(3):1-45.