12 Faith, Hope, and Love

An Interdisciplinary Approach to Providing Spiritual Care

The first half of this chapter is devoted to a review of the literature on the subject of faith and spirituality in children, especially children who are seriously ill, looking at faith, spirituality, and worldview, and examining the differences between screening and assessment. Much of what has been written begins from the perspective of data; while data is helpful to providing quality, interdisciplinary palliative care, it is not enough. The approach of this chapter places narrative and theology at the heart of the process and understanding. It will highlight the work of all the interdisciplinary team and examine the unique role of the professional chaplain.* The second part of the chapter will look at various case scenarios and the many ways the interdisciplinary team can participate in faith and/or spiritual care of the pediatric palliative care patient.

A review of the literature suggests that there is much work to be done in addressing the spiritual needs of pediatric palliative care patients. A survey conducted in 2008 by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life polled 36,000 Americans concerning their religious and spiritual beliefs. The results revealed that 92 percent of American adults believe in “God or a universal spirit.”1 Although this poll was limited to American adults, the findings support the idea that spirituality is an inherently universal aspect of human beings. While the importance of spirituality seems to be of increasing concern, there are few articles on the subject and most identify significant challenges in providing spiritual care in a healthcare setting. Most articles on the topic are written by nursing professionals and are intended for nurses. There is little information regarding the role of the interdisciplinary team in meeting the spiritual needs of children, although a few writers emphasize the need for collaboration.2

Writers in the field agree that spirituality is important to children and that spiritual concerns are particularly significant during times of serious illness.3 It is recognized that the distinction between spirituality and religious belief is important yet often overlooked,4 and that developmentally appropriate assessment is necessary but there is a lack of validated tools in addition to some confusion about who is best equipped to make these assessments.5 It is also clear that nurses, physicians, and chaplains are aware that spiritual needs are not adequately addressed.6 Among the identified barriers to optimal spiritual care are inadequate staffing of pastoral care departments, lack of training on the part of clinical staff, discomfort due to lack of knowledge or skill, and priority being given to medical concerns at the expense of holistic care.7 The general conclusion is that addressing spiritual needs in the child with a life-threatening illness is “an area that deserves continued exploration and attention.”7

Spirituality and World View

The diagnosis of a serious illness is a life changing event that not only interrupts8 our day-to-day activities but may also disrupt our world view. Children who have been cared for by loving parents know the world as a safe place and trust that they can rely on their family to provide for their safety. The onset of a serious illness changes that understanding. The role of the parent shifts as doctors become the most powerful figures in the child’s life, and parents may now feel unable to protect their son or daughter from pain and discomfort.

The question of faith and/or spiritual development

The task of human beings is to grow and learn. Development is a given on many levels and, unless limited by neurological, biological, or psychosocial factors, will follow recognizable patterns. All development is influenced by the many cultures9 in which an individual is embedded, perhaps none more so than the development of spiritual and/or faith concepts and needs. We cannot, with any certainty, describe specific faith development in children; we can only generalize about the ways faith development is related to human development. Each child, and each family system, must be understood as a unique entity. Exploring the cultures, which give each family its sense of meaning and purpose and upon which they will base much of their decision-making, is a vital process for the professional.

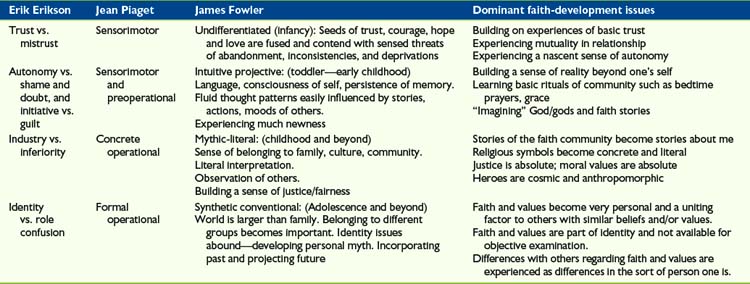

Developmental models are inclined to focus on stages. The human mind extrapolates that progress through these stages is success. Yet Erik Erikson, the progenitor of modern developmental theory (The Child and Society), cautioned his readers to be aware that all persons carry within themselves the potential future stages as well as the resources and unresolved issues of former stages. A person is never statically in one stage. Faith development, per James Fowler (Stages of Faith) is aligned with other psychosocial and biological development (Table 12-1). However, progress through faith-development stages does not tell us that a person’s faith is better, more developed, or better able to support them through crises. The development stage of one’s faith is influenced by culture and world view and frequently chosen because it assists the individual in making sense out of his or her life.

As human beings, one of our first tasks is to trust and to explore who we are in relationship to those we trust. The child who goes to sleep in a crib, in a dark room, is not only expressing trust in his parent, but also communicating a basic trust in the creation. As we grow and become more discerning and articulate, we begin to choose what it is in which we will have faith. A child makes choices about how open or closed she is to the world around her, to others, and to various concepts and practices offered by her family and communities. Children then begin to notice that what they receive is not to be taken for granted; they are able to express gratitude and desire the gratefulness of others. As trust and relationship are confirmed in the events of a child’s life, the child experiences and articulates what loss means, what regret and sorrow are, and how she or he is connected to, and a participant in, what the child believes to be the expectations and promises of living.10

Where trust and communion, being cared for, and caring for others are disrupted, every other aspect of the child’s psychosocial and spiritual development is also disrupted. A life- threatening injury or illness calls into question the intent or reality of something other or holy that is watching over the child. Every other concept which the child has integrated into his or her personal identity to this point will undergo some re-examination. What was easy, and practiced without much thought, such as gratitude, becomes difficult and problematic. Depending upon the cultures of the child’s community, the child may become more focused on remorse or responsibility. Children often return to earlier stages of psychosocial coping when feeling exposed and unsure; this may or may not be true of children and their faith-based, or spiritual, perspectives. Erikson emphasized that development is process not progress, at least not entirely, and that each stage holds the following ones in potential and the past ones as resource and unresolved issues. There are children of all ages who need the more concrete, me-oriented concepts and ideals. However, there are other children of all ages for whom concepts or symbols become transparent,11 the universe suddenly coherent, and vision transformed. Neither is better.

The work of faith, or spiritual, development happens along two fronts. One is the cultures in which the child is embedded, and the other includes all the experiences and relationships which the child internalizes as her or his own particular world view. It is never enough to know the tenets of a child’s cultural and/or faith environment, one must know the child (Table 12-1).

Faith and/or Spiritual Screening and Assessment

This model is based on a generalist-specialist model of care in which board-certified chaplains are considered the trained spiritual care specialists. Detailed assessment and complex diagnosis and treatment are the purview of the board-certified chaplains working with the interdisciplinary team as the spiritual-care experts.12

Screening tools presently available

There is another characteristic of the faith and/or spiritual assessment when the patient in palliative care is a child. In almost all other health care situations, patients are the primary decision-makers as long as they are competent to make informed decisions. This is not true for pediatric patients. Not only are children not their own primary decision makers, but also they, or their hopes, wishes, and concerns, may fall far down the family’s list of what is important. This refers not only to the child’s parents, but also to extended family members, and/or community members depending on the culture and/or ethnicity of the patient/family. Therefore, the effective faith and/or spiritual assessment is one that takes into account the entire family system.13 It weakens the effectiveness of the child’s narrative as a means to assist the child if we do not understand how other family members narratives may either subvert or overpower the child’s. As the team gathers the narratives, the chaplain, team members, and perhaps the family’s personal clergy, can evaluate where there may be power struggles in the family, whether keeping secrets may impact how the child understands his or her circumstances, and if this will affect the care being provided by the interdisciplinary team. Many other aspects of how the family functions, or does not function, may also be instrumental in planning appropriate care. Ideally, for work in pediatric palliative care, the professional chaplain should have some training in family systems theory across cultures, child, and spiritual development so that her or his evaluation is grounded and not merely guesswork. To provide this training could be an important commitment of a palliative care program.

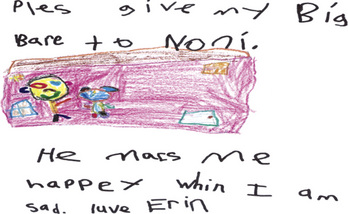

Providing Spiritual Care: A Theological Concept

Sally,14 14, expressed to a nurse; “I know I’m dying, but, please, don’t tell my mom, ‘cause she can’t handle it.” Sally and her mother never had a conversation about what Sally wanted for her death, although the case team attempted to facilitate it. Sally’s mother was intent on protecting her daughter; Sally was intent on protecting her mother. Sally, fortunately, was able to talk with one nurse and the social worker about her beliefs, her fears, and what she wanted for herself. Her mother excluded herself from that gift. However, the team respected Sally’s mother’s values, which was essential to her being able to cope. For patients who have difficulty talking about their feelings, art, music, and play therapy can provide powerful outlets for creative expression. Therapists and psychologists, in providing therapeutic interventions, become spiritual caregivers (Figs. 12-1 and 12-2).

Children also need permission to die. This is often something families have difficulty granting.

Tommy, 10, was hospitalized while waiting for a liver transplant. It was clear to the care team that he was very frightened, although he did not want to talk about how he was feeling. His mother was a single parent and could not spend the night with him very often. Tommy had trouble sleeping and would often wake from nightmares. These behaviors reflect the spiritual needs and/or distress of feeling secure, having agency, and trusting in a world that has a purpose for one’s self and others. Tommy came from a very religious Christian family and enjoyed going to church and saying prayers. He was also a talented and creative artist, and a bright and gifted student. One of his favorite activities in the hospital was playing video games. The care team met to discuss how they might best support Tommy during his hospital stay (Table 12-2).

| Discipline | Role In providing spiritual care |

|---|---|

| Physicians | Encourage Tommy to ask questions about his medical condition. Spend a few extra minutes playing video games with him when possible. |

| Nursing | Spend time sitting with Tommy at bedtime reading a favorite story when possible. |

| Social work |

1 Salmon J. Most Americans Believe in Higher Power, Poll Finds. 2008. The Washington (DC) Post, Section A, p 2, June 24,

2 Fina D. The spiritual needs of pediatric patients and their families. AORN J. 1995;62(4):556-564.

3 Bluebond-Langner M. The private worlds of dying children. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

4 Heilferty C. Spiritual development and the dying child: the pediatric nurse practitioner’s role. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18(6):271-275.

5 Hart D., Schneider D. Spiritual care for children with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1997;13(4):263-270.

6 Feudtner C., Haney J., Dimmers M. Spiritual care needs of hospitalized children and their families: a national survey of pastoral care providers’ perceptions. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e67-e72.

7 McSherry W., Smith J. How do children express their spiritual needs? Paediatr Nurs. 2007;19(3):17-20.

8 Frank A. The wounded storyteller: body, illness, and ethics. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

9 Ting-Toomey S. Communication across cultures. New York: Guilford Press, 1999.

10 Pruyser P.W. Personal problems in pastoral perspective: the minister as diagnostician. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1976.

11 Coleridge ST: The “transparent” symbol is a theme of the work as a whole, Biographia Literaria

12 Puchalski C., et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 12(10), 2009.

13 The Professional Chaplains at The Children’s National Medical Center have developed a Family System Assessment “tool.” It includes a page that assists the chaplain in documenting various family strengths and weaknesses. We emphasize this is not a “one visit” tool, but a process of gathering faith/spiritual narrative. Available upon request to Rev. Kathleen Ennis-Durstine, BCC at kennisdu@cnmc.org.

14 All names are pseudonyms and details have been conflated between several similar cases.

15 McSherry M., Kehoe K., Carroll J., et al. Psychosocial and spiritual needs of children living with a life-limiting illness. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:609-629.

16 Cole R. The spiritual life of children. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990.

17 Sommer D. The spiritual needs of dying children. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1989;12:225-233.

18 Sourkes B. Armfuls of time. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press, 1995.

19 Stuber M., Houskamp B. Spirituality in children confronting death. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin. 2003;13:127-136.

20 Hufton E. Parting gifts: the spiritual needs of children. J Child Health Care. 2006;10(3):240-249.

Bull A Bull A, Gillies M: Spiritual needs of children with complex healthcare needs in hospital, Paediatr Nurs 19(9):34–38.

Bluebond-Langner M. The private worlds of dying children. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Cole R. The spiritual life of children. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1990.

Davies B., Brenner P., Orloff S., et al. Addressing spirituality in pediatric hospice and palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2002;18(1):59-67.

Erikson E. Childhood and society. New York: WW Norton, 1950.

Fina D. The spiritual needs of pediatric patients and their families. AORN J. 1995;62(4):556-564.

Fochtman D. The concept of suffering in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2006;3(2):92-102.

Ford G. Hospitalized kids: spiritual care at their level. J Christ Nurs. 2007;24(3):135-140.

Feudtner C., Haney J., Dimmers M. Spiritual care needs of hospitalized children and their families: a national survery of pastoral care providers’ perceptions. Pediatrics. 2003;111(1):e67-e72.

Frank A. The wounded storyteller: body illness, and ethics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Fowler J. Stages of faith: the psychology of human development. New York: Harper Collins, 1981.

Hart D., Schneider D. Spiritual care for children with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1997;13(4):263-270.

Heilferty C. Spiritual development and the dying child: the pediatric nurse practitioner’s role. J Pediatr Health Care. 2004;18(6):271-275.

Hufton E. Parting gifts: the spiritual needs of children. J Child Health Care. 2006;10(3):240-249.

McEvoy M. An added dimension to the pediatric health maintenance visit: the spiritual history. J Pediatr Health Care. 2000;14:216-220.

McSherry M., Kehoe K., Carroll J., et al. Psychosocial and spiritual needs of children living with a life-limiting illness. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:609-629.

McSherry W., Smith J. How do children express their spiritual needs? Paediatr Nurs. 2007;19(3):17-20.

Salmon J. Most american believe in higher power, poll finds. 2008. Washington Post [Washington, DC] June 24

Sommer D. The spiritual needs of dying children. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1989;12:225-233.

Stuber M., Houskamp B. Spirituality in children confronting death. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin. 2003;13:127-136.

Quinn J. Perspectives on spiritual development as part of youth development. New Dir Youth Dev. 2008;118:73-78.

* Board Certified Professional Chaplain: This individual possesses a Master’s Degree in Theology/Divinity, is ordained or endorsed by a particular faith/spiritual community, has completed a minimum of 1600 hours of clinical training under supervision, demonstrates clinical proficiency through written materials and interview with a board of Certified Chaplains from either the Association of Professional Chaplains, the National Association of Catholic Chaplains, or the National Association of Jewish Chaplains. Maintaining professional certification requires 50 continuing education hours per year and scheduled peer reviews to assure competency.