Fair Game

Answers

Case 38

Case 39

Case 40

2 Name at least three causes of chronic infiltrative lung disease that are associated with a basilar and subpleural distribution of abnormalities.

Answers

Case 41

Case 42

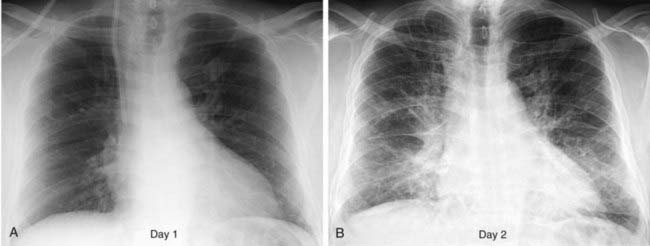

1 What is the most likely cause for the acute interstitial process demonstrated in the second figure?

Answers

Case 42

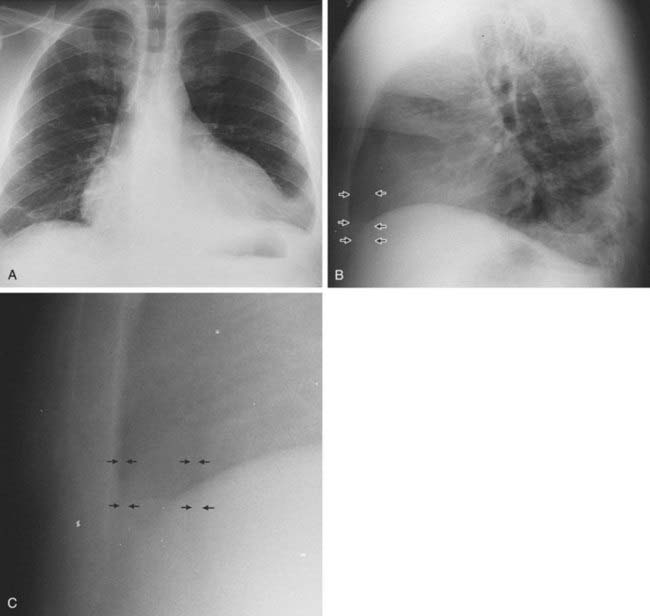

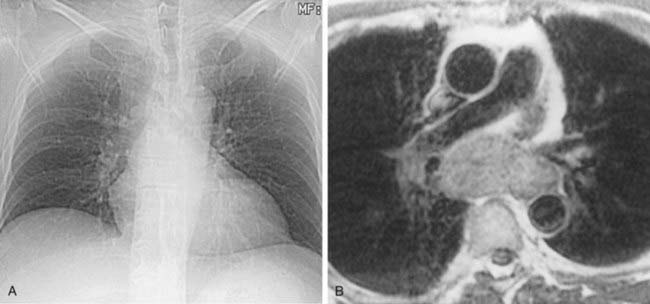

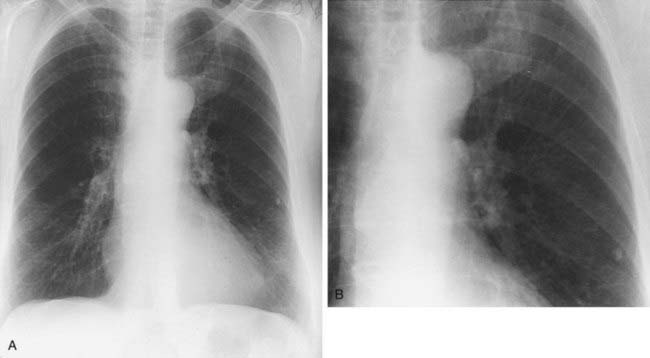

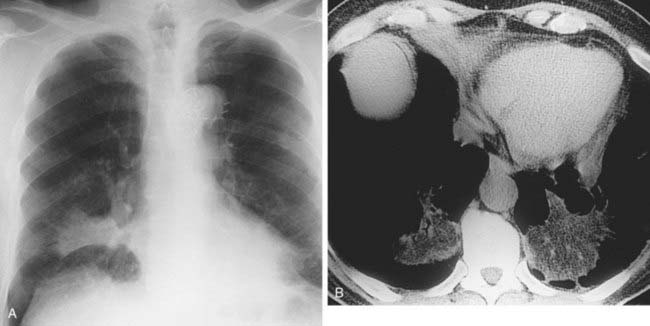

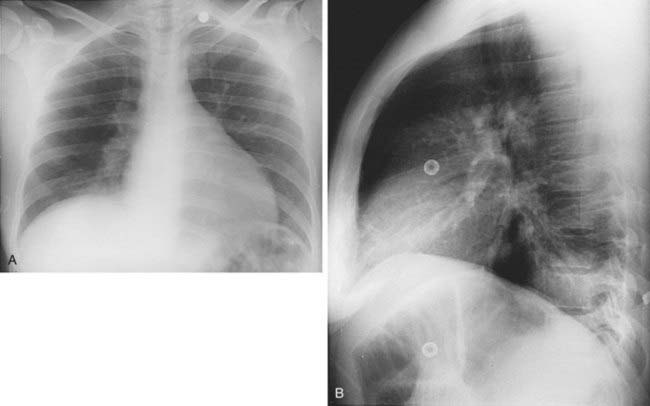

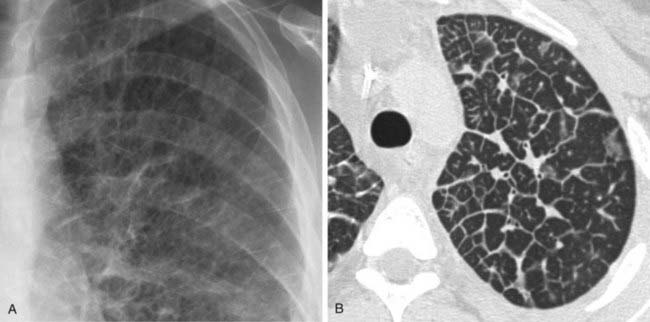

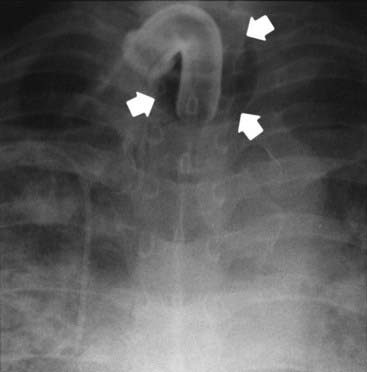

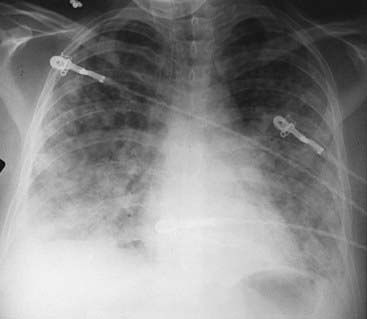

Interstitial Edema

2 Kerley A lines are centrally located, radiate from the hila, and measure 2 to 6 cm in length; Kerley B lines are peripherally located, usually extend to the pleural surface, and measure less than 2 cm in length.

4 Peribronchial cuffing, indistinct pulmonary vessels; interlobular septal thickening (Kerley lines), and thickening of the fissures.

Case 43

Answers

Answers

Case 44

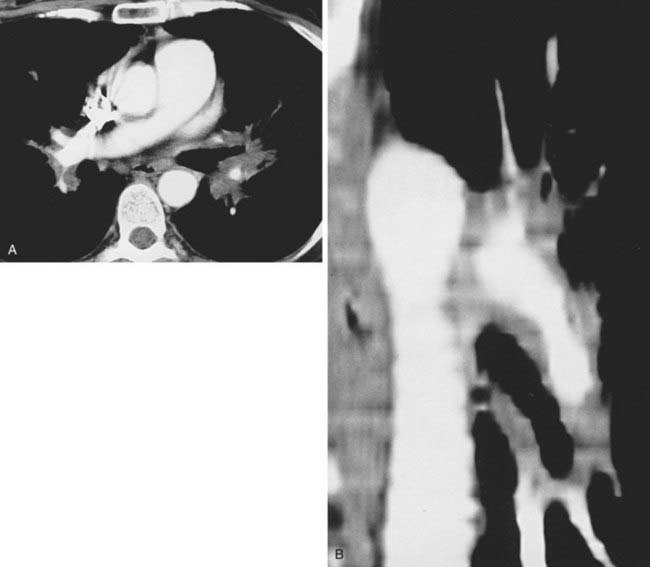

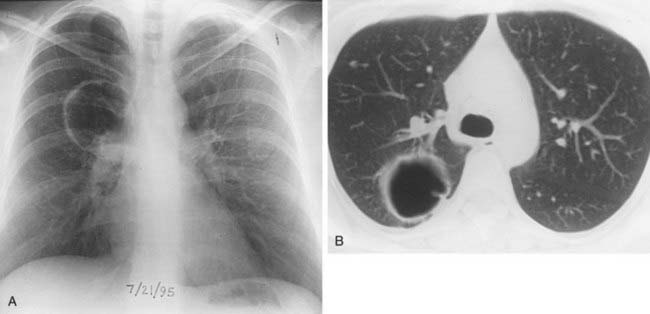

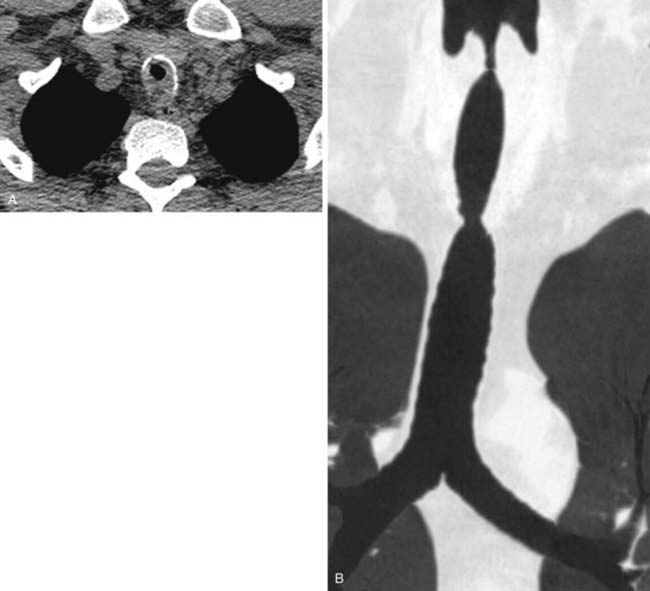

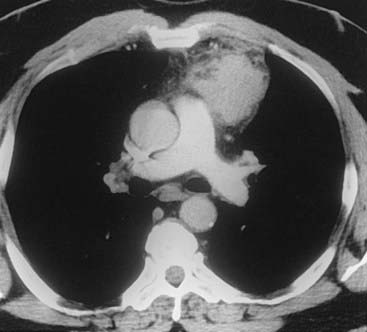

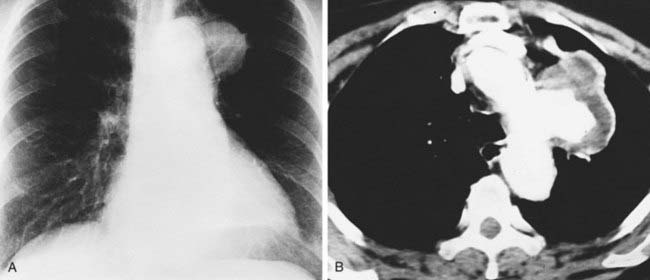

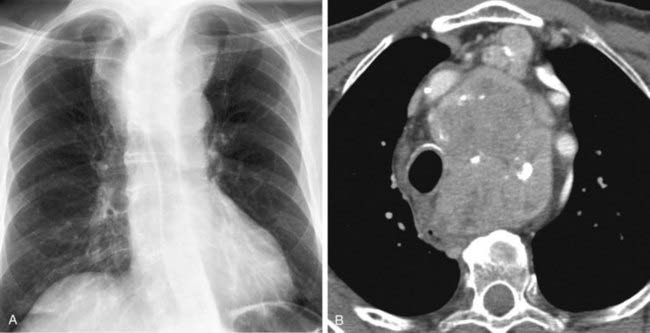

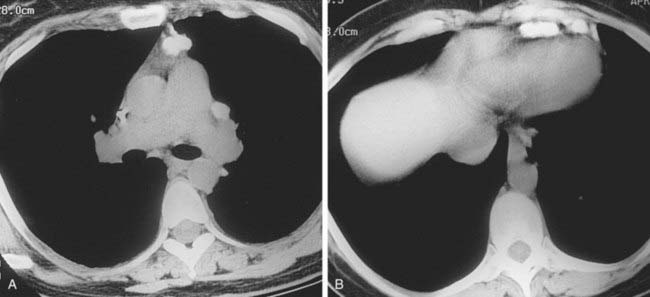

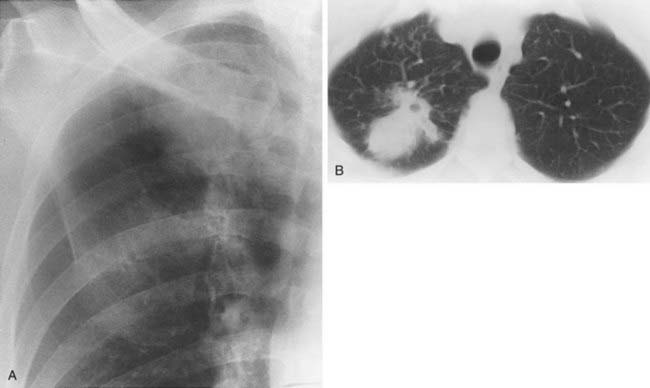

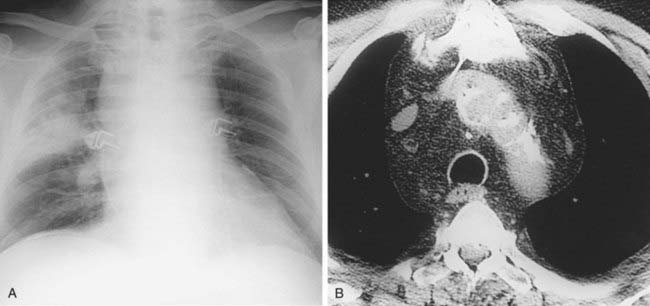

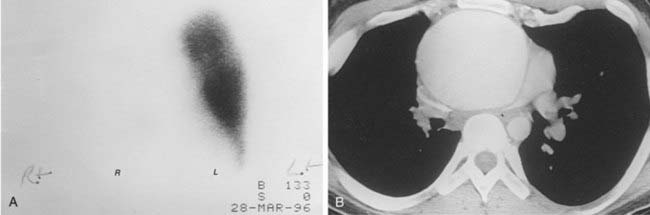

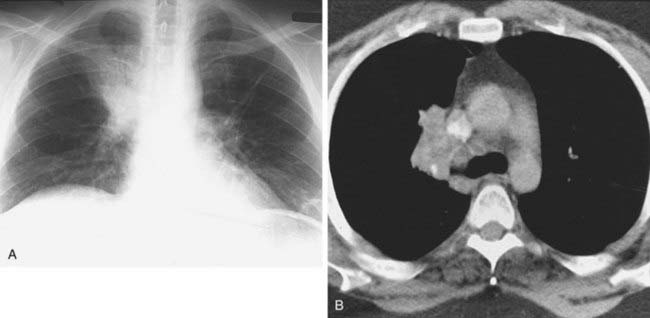

Arteriovenous Malformation

2 Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler-Weber-Rendu disease, which is characterized by telangiectasias, AVMs, and aneurysms in multiple organ systems (including pulmonary, gastrointestinal, cutaneous, and central nervous system).

Case 46

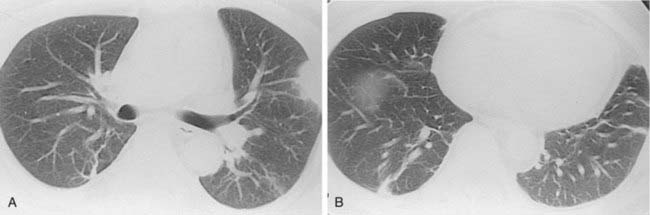

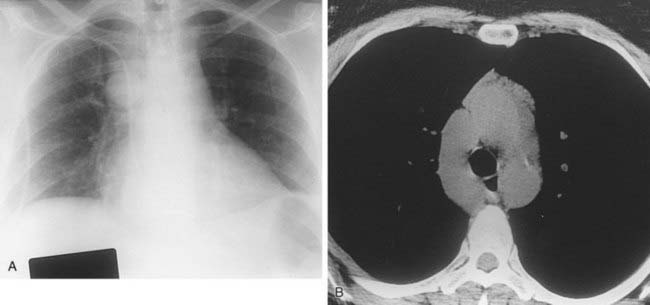

1 What is the differential diagnosis for the wedge-shaped, peripheral consolidation in the left lung in the first figure?

2 What is the significance of the identification of a feeding vessel directed toward the apex of the consolidation?

Answers

Case 47

1 What is the differential diagnosis of multiple lung nodules or masses in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)?

Answers

Answers

Case 52

Case 54

1 Which type of infection most commonly presents with multiple poorly defined lung nodules in an immunosuppressed patient?

Case 55

Case 56

Case 57

Case 58

Answers

Case 59

Case 60

Answers

Case 60

Case 61

Answers

Case 61

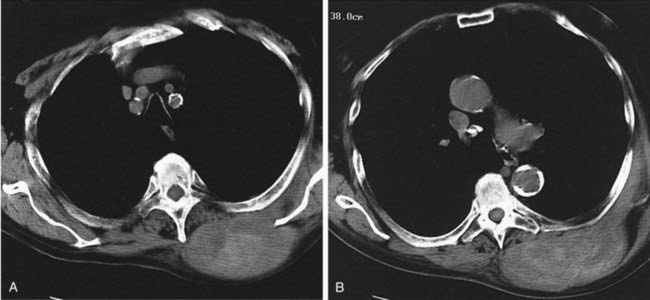

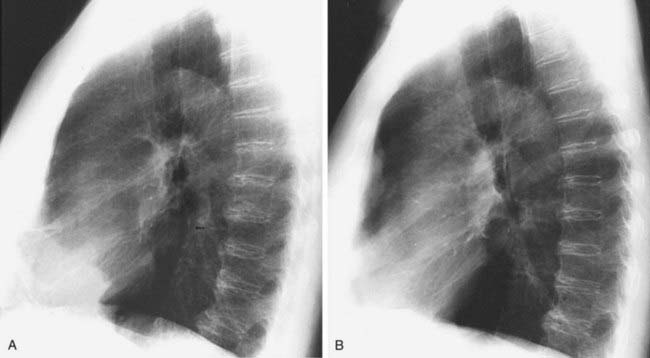

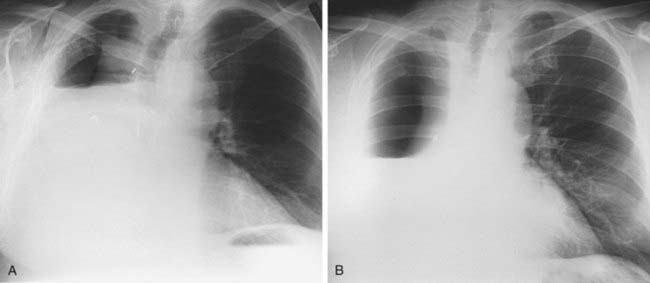

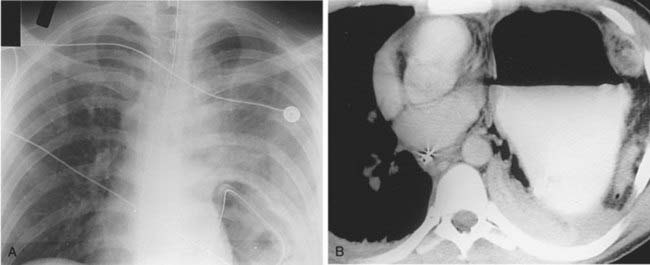

Bronchopleural Fistula

3 Failure of the pneumonectomy space to fill with fluid; abrupt decrease in the air-fluid level in the pneumonectomy space; contralateral shift of the mediastinum following pneumonectomy; and identification of air in a previously completely opacified pneumonectomy space.

Answers

Case 64

1 Name three possible diagnoses for the chest radiograph findings in this patient with breast cancer who is receiving chemotherapy.

Case 66

2 Do MRI signal characteristics of lymph nodes effectively distinguish between benign and malignant lymph nodes?

Answers

Answers

Case 69

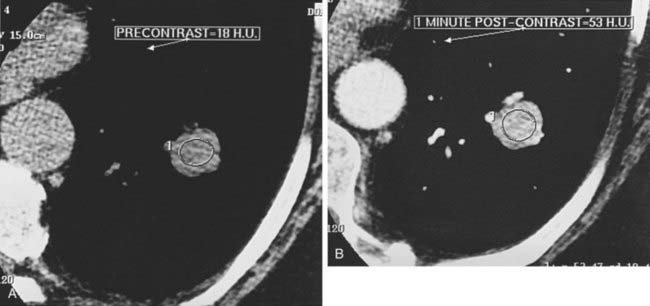

2 Precontrast and 1-minute postcontrast images demonstrate nodule enhancement of 35 Hounsfield units. Is this degree of enhancement diagnostic of a benign entity?

Case 70

Answers

Answers

Case 72

Case 73

Case 74

1 What is the most likely cause for the parenchymal abnormality observed in the right lower lobe in this patient?

Answers

Case 75

2 Which of these entities are most closely associated with a reticular and nodular pattern on chest radiographs?

Answers

Answers

Case 77

Case 78

Case 79

Answers

Answers

Case 80

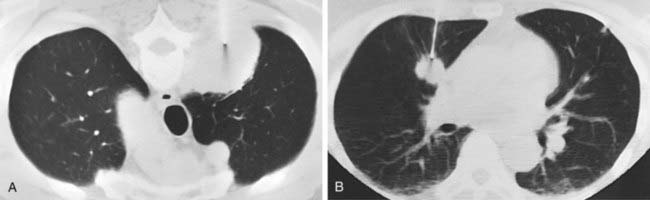

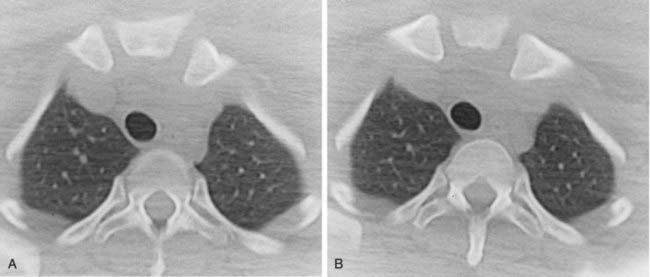

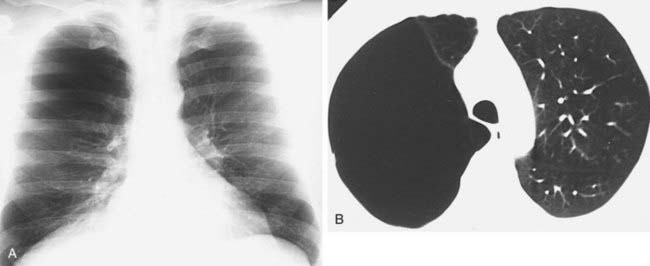

Bulla

1 A bulla is a sharply demarcated airspace measuring more than 1 cm in diameter and possessing a well-defined wall less than 1 mm in thickness.

2 A bleb is a small (less than 1 cm) gas-containing space within the visceral pleura or in the subpleural lung.

Case 81

Answers

Case 82

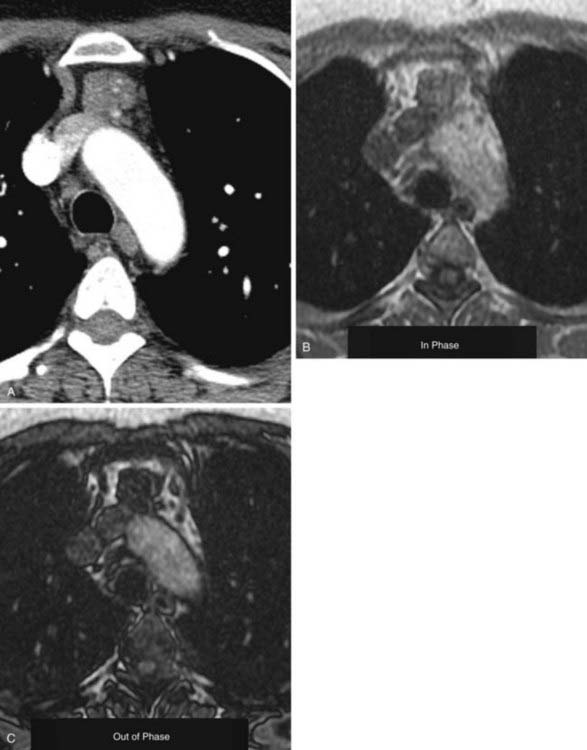

1 A region-of-interest measurement of this mass demonstrated Hounsfield units consistent with fat attenuation. What are the two most likely diagnoses?

Answers

Case 83

1 Which type of viral pneumonia typically presents with a diffuse distribution of poorly defined lung nodules?

Answers

Case 84

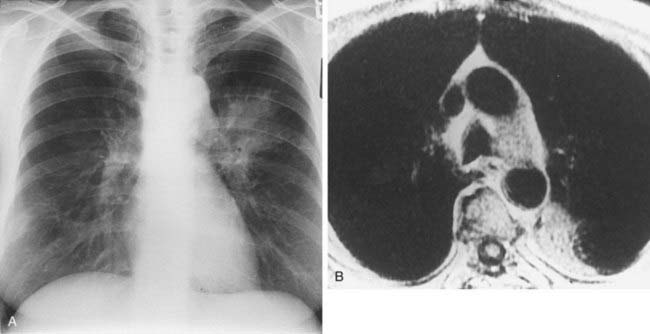

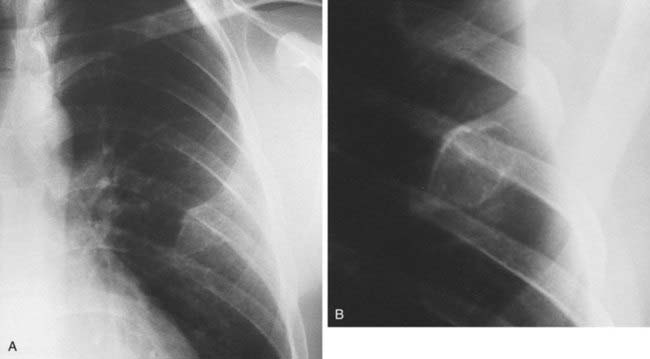

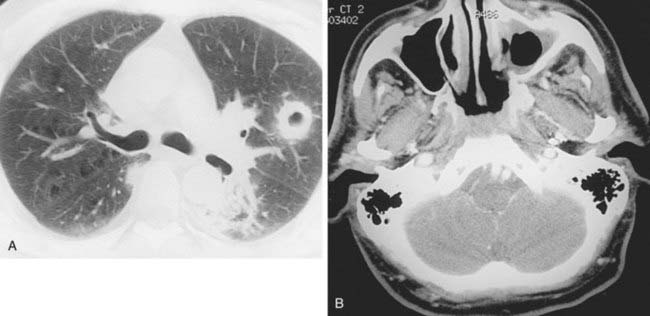

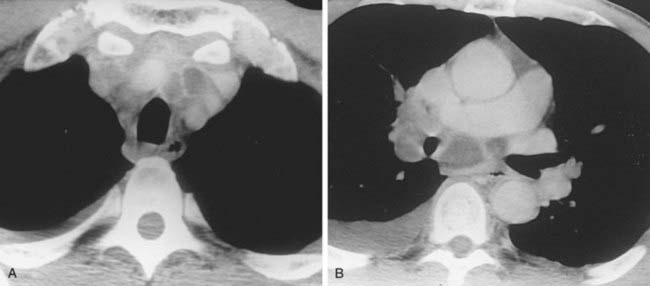

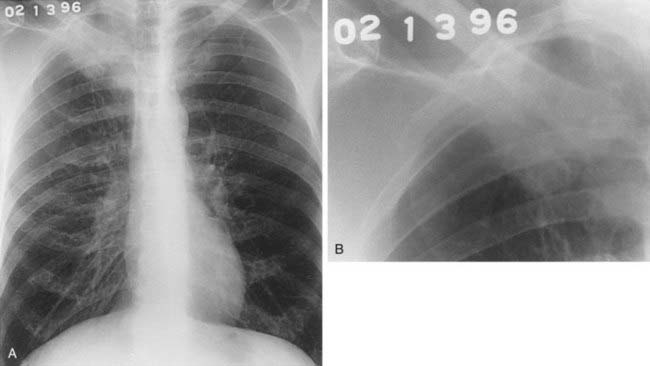

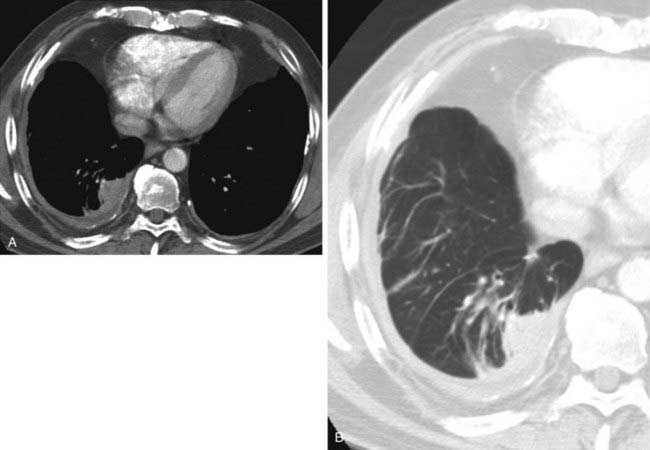

Apical Cap Secondary to Extrapleural Abscess Extending From the Neck

1 Primary lung cancer, lymphoma extending from the neck or mediastinum, extrapleural hematoma related to injury, extrapleural abscess extending from the neck, and radiation fibrosis.

Reference

McLoud TC, Isler RJ, Novelline RA, et al: The apical cap. AJR Am J Roentgenol 137:299-306, 1981.

Case 85

Case 86

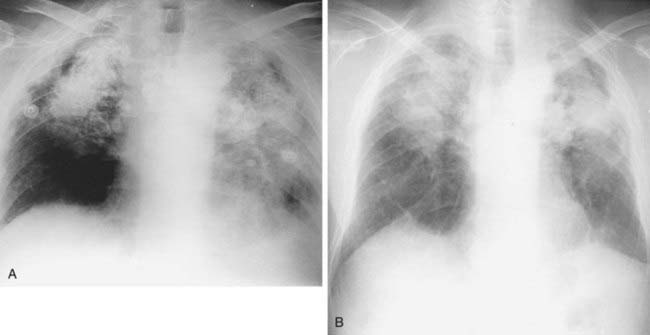

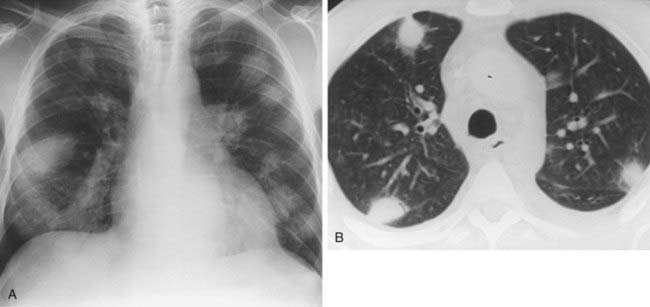

1 This patient has a history of lymphoma and is being treated with bleomycin. What is the most likely cause for the interstitial opacities observed in the first and second figures?

Case 87

1 In an HIV-positive patient, which fungal infection is most likely to present with pulmonary nodules, pleural effusion, and lymph node enlargement?

Case 88

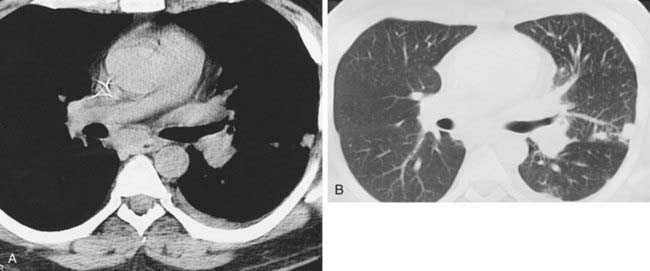

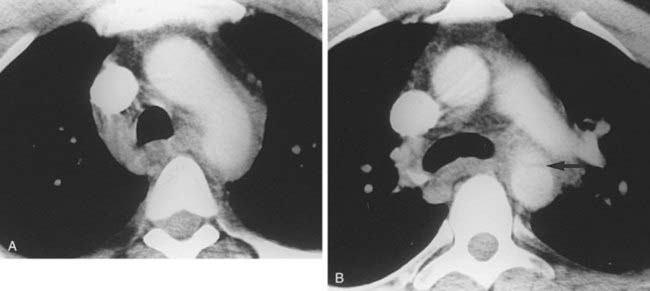

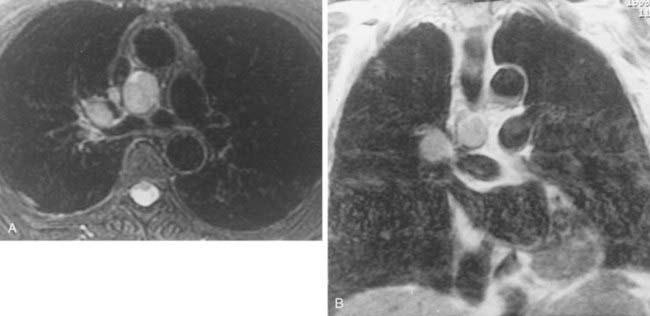

1 Transthoracic biopsy of the lung mass shown in the figures revealed NSCLC. Is the presence of an enlarged aortopulmonary window lymph node sufficient proof of metastatic nodal disease?

Answers

Case 88

Lung Cancer With N2 Nodal Disease

Answers

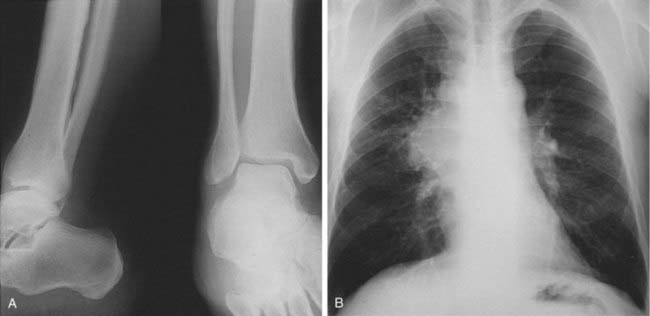

Case 90

1 What is the term used to describe the presence of periosteal reaction in association with pulmonary disease?

Case 91

Case 92

Answers

Case 93

Answers

Case 94

Answers

Case 95

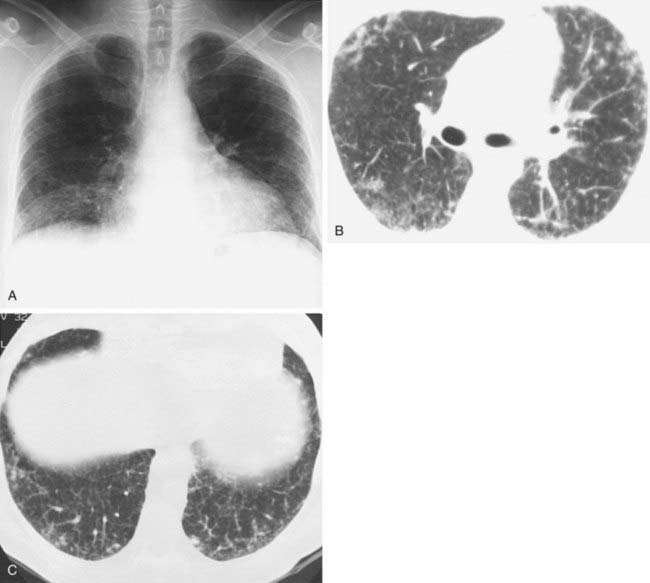

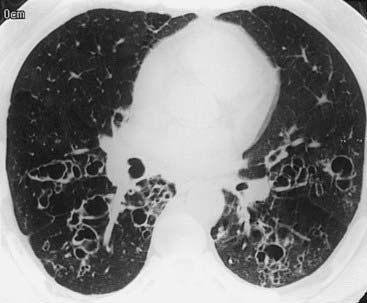

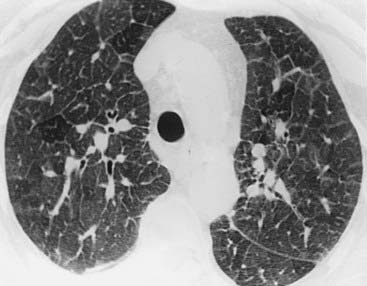

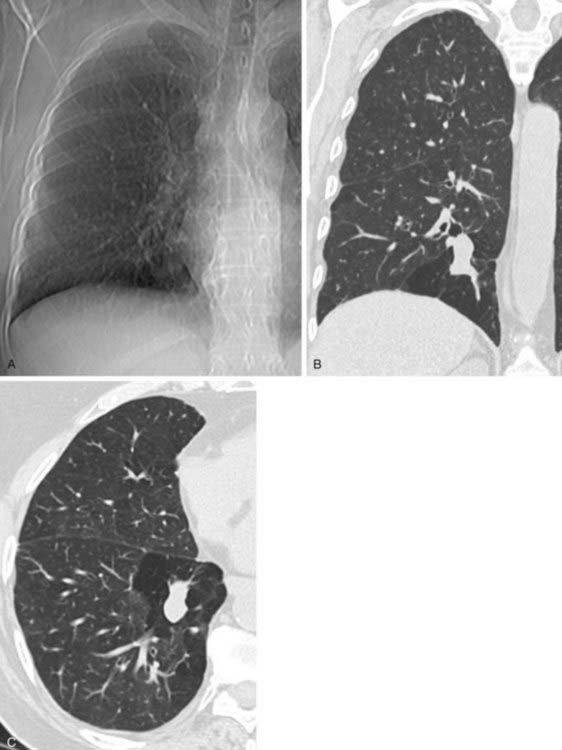

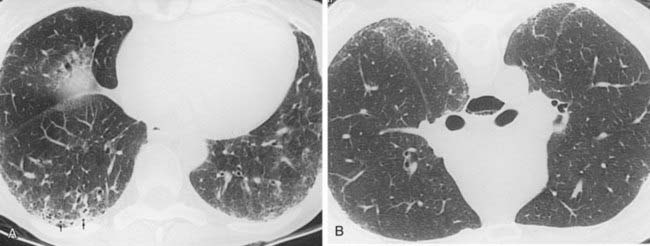

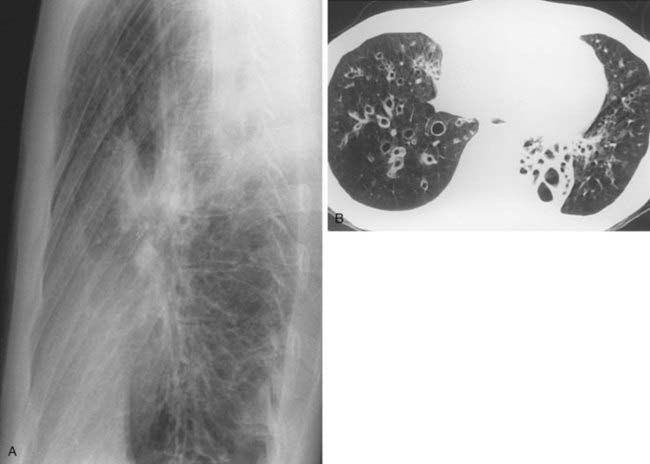

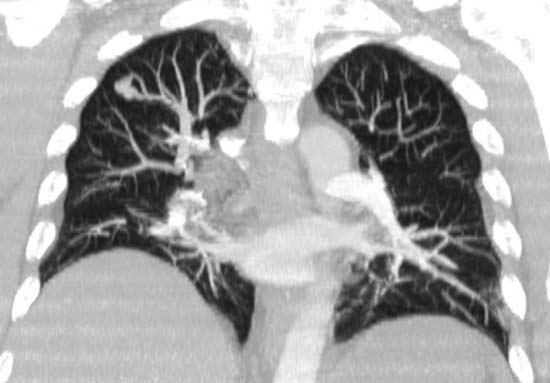

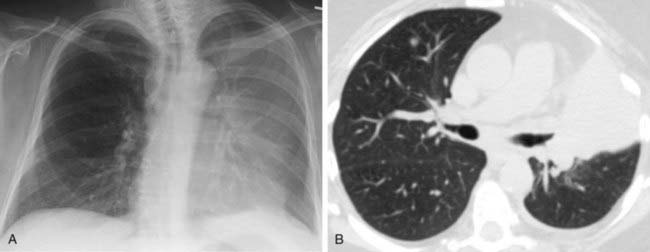

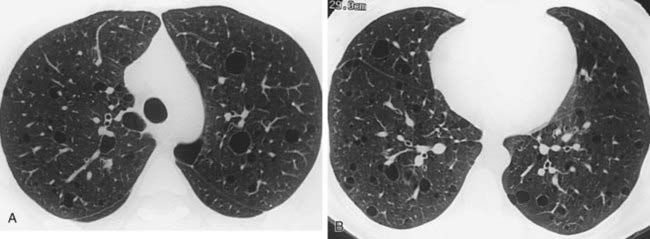

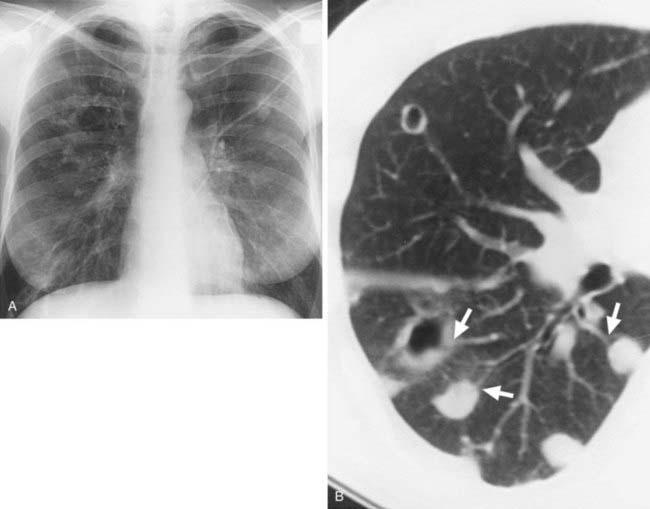

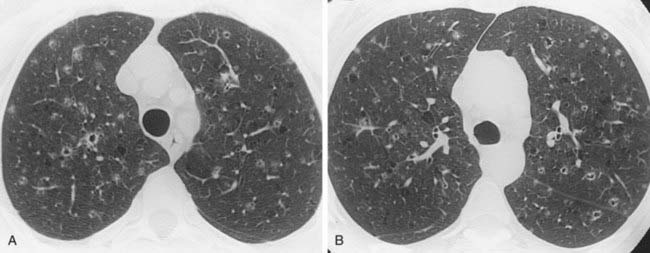

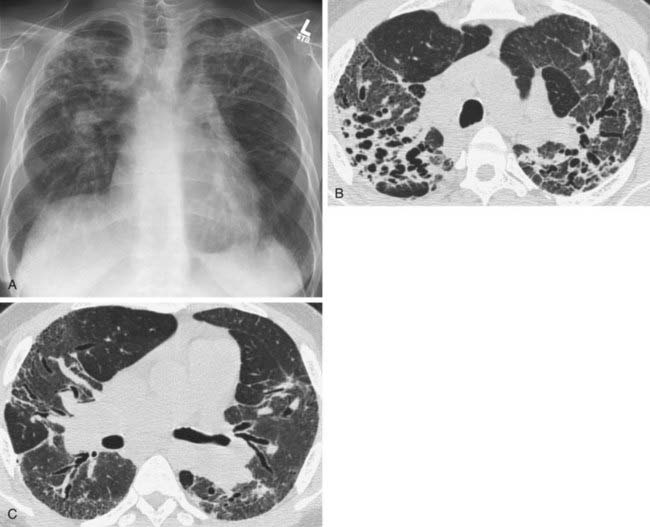

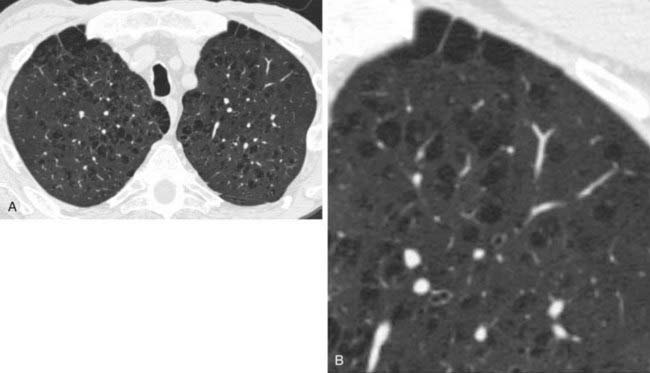

Bronchiectasis

2 Many of the cystic spaces are connected, several run parallel to adjacent vessels (“signet ring sign”), and several have air-fluid levels.

4 Williams-Campbell syndrome, cystic fibrosis, primary hypogammaglobulinemia, “yellow nail” syndrome, immotile cilia syndrome (Kartagener’s syndrome), Young’s syndrome, and Mounier-Kuhn syndrome.

Case 96

Answers

Case 97

Case 98

Case 99

Case 100

Answers

Answers

Case 101

Bronchial Atresia

1 Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), obstructing endobronchial tumor, congenital bronchial atresia (CBA), cystic fibrosis.

2 Bronchial (pulmonary) isomerism syndrome, bronchial atresia, congenital bronchiectasis (e.g., cystic fibrosis, Williams-Campbell syndrome), supernumerary bronchus, pig bronchus, cardiac bronchus.

Answers

Case 102

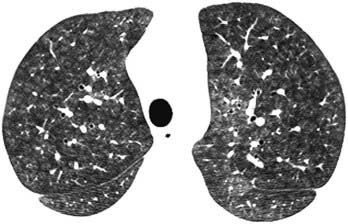

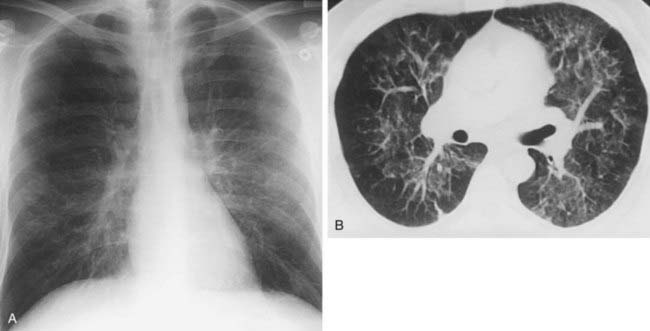

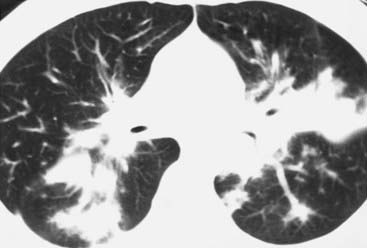

Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis

1 Subacute hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP), respiratory bronchiolitis, respiratory bronchiolitis–interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD), PCP, pulmonary LCH.

3 Emphysema, lung cancer, respiratory bronchiolitis, RB-ILD, desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), PLCH, chronic bronchitis.

Case 103

Answers

Case 105

Answers

Case 106

1 Regarding solitary pulmonary nodules (SPNs), which is most likely to be malignant: a solid nodule, a ground-glass nodule, or a semi-solid nodule of mixed attenuation (ground-glass and solid components)?

) scan?

) scan?

mismatches, and improved mechanics of breathing. Patients are selected for the procedure based on a variety of clinical and imaging parameters. With regard to imaging features, preliminary data suggest that patients with a heterogeneous distribution of emphysema with an upper lobe predominance are most likely to benefit from this procedure.

mismatches, and improved mechanics of breathing. Patients are selected for the procedure based on a variety of clinical and imaging parameters. With regard to imaging features, preliminary data suggest that patients with a heterogeneous distribution of emphysema with an upper lobe predominance are most likely to benefit from this procedure.