Chapter 16 FAILURE TO THRIVE

Causes of Failure to Thrive

Behavioral problems affecting eating

Central nervous system (CNS) damage

Disturbed parent-child relationship

Incorrect preparation of formula (too dilute/concentrated)

Key Historical Features

Key Physical Findings

Height, weight, and head circumference plotted on a growth curve and compared with previous measurements. A corrected age should be used for preterm infants. Charts for special populations should be used when appropriate.

Height, weight, and head circumference plotted on a growth curve and compared with previous measurements. A corrected age should be used for preterm infants. Charts for special populations should be used when appropriate.

General examination for dysmorphic features suggestive of a genetic disorder impeding growth or any evidence of underlying disease impairing growth

General examination for dysmorphic features suggestive of a genetic disorder impeding growth or any evidence of underlying disease impairing growth

The general assessment should also evaluate for signs of wasting, as well as an assessment of the severity and possible effects of malnutrition

The general assessment should also evaluate for signs of wasting, as well as an assessment of the severity and possible effects of malnutrition

Head and neck examination for craniofacial abnormalities such as severe micrognathia, cleft lip, or cleft palate. The quality of tears and dryness of mucous membranes should be noted. The fontanelles should be evaluated to determine whether they are sunken

Head and neck examination for craniofacial abnormalities such as severe micrognathia, cleft lip, or cleft palate. The quality of tears and dryness of mucous membranes should be noted. The fontanelles should be evaluated to determine whether they are sunken

Cardiopulmonary examination for any evidence of cardiac or pulmonary disease

Cardiopulmonary examination for any evidence of cardiac or pulmonary disease

Abdominal examination for hepatomegaly or mass

Abdominal examination for hepatomegaly or mass

Extremity examination for edema

Extremity examination for edema

Skin examination for rashes, skin turgor, or skin changes

Skin examination for rashes, skin turgor, or skin changes

Musculoskeletal and skin examination for any evidence of physical abuse

Musculoskeletal and skin examination for any evidence of physical abuse

Genitourinary examination if sexual abuse is suspected

Genitourinary examination if sexual abuse is suspected

Suggested Work-up

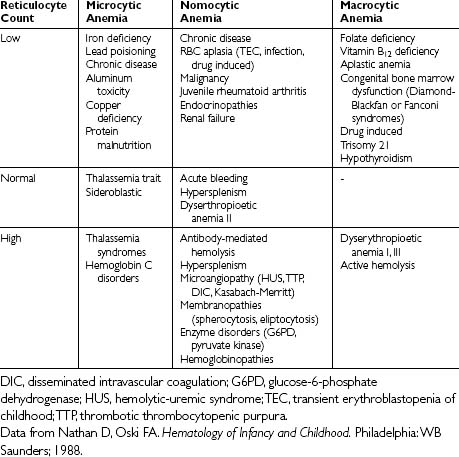

| Complete blood cell count (CBC) | To evaluate for anemia, infection, or malnutrition (decreased total lymphoryte count) |

| Electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, (BUN), and creatinine | To evaluate for renal disease |

| Serum bicarbonate | To evaluate for chronic acidosis |

| Fasting glucose | To evaluate for diabetes |

| Liver function tests, including total protein and albumin | To evaluate for liver disease and malnutrition |

| Serum prealbumin | To evaluate nutritional status |

| Iron studies (ferritin, iron, total iron binding capacity [TIBC]) | To evaluate for iron deficiency |

| Urinalysis and urine culture | To evaluate for UTI |

Additional Work-up

| HIV test | If HIV infection or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is suspected |

| Sweat chloride test | If cystic fibrosis is suspected |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) | If hyper- or hypothyroidism is suspected |

| Lead level | If lead poisoning is suspected |

| Stool studies for ova and parasites | If intestinal infection is suspected |

| Fecal fat analysis | If malabsorption is suspected |

| Serum immunoglobulins | If an immune deficiency is suspected |

| Purified protein derivative (PPD) | If tuberculosis is suspected |

| Selected radiologic studies | If abuse or infection is suspected |

| Serum insulin-like growth factor | If growth hormone deficiency is suspected |

| Tissue transglutaminase antibody, gliadin antibody, and endomesial antibody | If celiac disease is suspected |

| Radiologic evaluation for bone age | To help distinguish genetic short stature from constitutional delay of growth |

| Small intestine biopsy | To confirm a diagnosis of celiac disease |

1. Adamkin D.H. Feeding problems in the late preterm infant. Clin Perinatol. 2006;33(4):831–837.

2. Allen R.E. Nutrition in toddlers. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(9):1527–1532.

3. Block R.W., Kres N.F. and the Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect and the Committee on Nutrition. Failure to thrive as a manifestation of child neglect. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1234–1237.

4. Corbett S.S., Drewett R.F., Wright C.M. Does a fall down a centile chart matter? The growth and development sequelae of mild failure to thrive. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:1278–1283.

5. Frank D., Zeisel S. Failure to thrive. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1988;35:1187–1205.

6. Gahagan S., Holmes R. A stepwise approach to evaluation of undernutrition and failure to thrive. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1998;45:169–187.

7. Gubitosi-Klug R.A. Idiopathic short stature. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2005;34(3):565–580.

8. Krugman S.D., Dubowitz H. Failure to thrive. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:879–884.

9. Maggioni A., Lifshitz F. Nutritional management of failure to thrive. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1995;42:791–810.

10. Marsden D. Newborn screening for metabolic disorders. J Pediatr. 2006;148:577–584.

11. Rudolph C.D. Feeding disorders in infants and children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49(1):97–112.

12. Schechter M. Weight loss/failure to thrive. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:238–239.

13. Shah M.D. Failure to thrive in children. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:371–374.

14. Sills R.H. Failure to thrive: the role of clinical and laboratory evaluation. Am J Dis Child. 1978;132:967–969.

15. Smith M.M., Lifshitz F. Excess fruit juice consumption as a contributing factor in nonorganic failure to thrive. Pediatrics. 1994;93:438–443.