CHAPTER 103 Failed Back Surgery

Failed back surgery syndrome (FBSS) is a non-specific term that implies the final outcome of surgery did not meet the expectations of both the patient and the surgeon that were established before surgery.1 It should not and does not suggest that the patient failed to get total pain relief or did not return to full function.

The patient must also have realistic expectations, and must rely to some degree on the surgeon’s input. In patients with chronic pain, an improvement in 0–10 numerical rating scale (NRS) or visual analog score (VAS) of 1.8 units is equivalent to a change in pain of about 30%, which will be considered by most patients as a ‘somewhat satisfactory result.’2 An improvement in NRS or VAS of 3 units or more is equivalent to a change in pain of about 50%, which most patients will consider an ‘extremely satisfactory result.’

STRUCTURAL ETIOLOGIES OF FAILED BACK SURGERY

In this section, the author will briefly review the most common structural causes of FBSS based on published data.3–5 These are lateral canal stenosis (foraminal stenosis), recurrent or residual disc herniation, one or more painful discs, neuropathic pain, facet joint pain, and sacroiliac joint pain. It is interesting to note that the causes of FBSS and the causes of chronic low back pain (LBP) are quite similar. By combining a careful history, physical examination, and specialized testing, the structural cause of FBSS can be delineated in more than 90% of patients.4,5 In some patients, the structural cause of the FBSS was present prior to surgery and was not adequately addressed (e.g. painful disc, lateral canal stenosis, facet or sacroiliac joint [SIJ] pain). In others the problem occurred after surgery, either as a direct consequence of the surgery (e.g. SIJ pain after fusion, pseudoarthrosis, etc.) or as new and unrelated pathology.

In 1981, Burton et al. reported an analysis of several hundred patients with FBSS.3 They found that about 58% had lateral canal stenosis (foraminal stenosis), 7–14% had central canal stenosis, 12–16% had recurrent (or residual) disc herniations, 6–16% had arachnoiditis, and 6–8% had epidural fibrosis. Other less common causes in their series included neuropathic pain, chronic mechanical pain, painful segment (disc) above a fusion, pseudoarthrosis, foreign body, and surgery performed at the wrong level. They were unable to establish a definitive diagnosis in less than 5% of their patients despite the fact that their study was done early in the computed tomography (CT) scan era and well before magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. They did use discography.

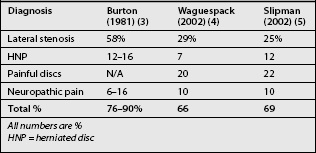

There have been major advances in diagnostic testing since the Burton paper. In 2002, Waguespack et al.4 and Slipman et al.5 each independently reported their results of evaluations of patients with FBSS (Table 103.1). Waguespack et al. performed a retrospective review of 187 patients who presented to a tertiary care spine center. They established a predominant diagnosis in 95% of their patients. Slipman et al. performed a similar study in which they reached a diagnosis in more than 90% of patients as well. In these two recent studies the most common structural causes of FBSS were foraminal stenosis (25–29%), painful disc (20–22%), pseudoarthrosis (14%), neuropathic pain (10%), recurrent disc herniation (7–12%), instability, facet pain (3%), and sacroiliac joint pain (2%), among some others (Table 103.2).

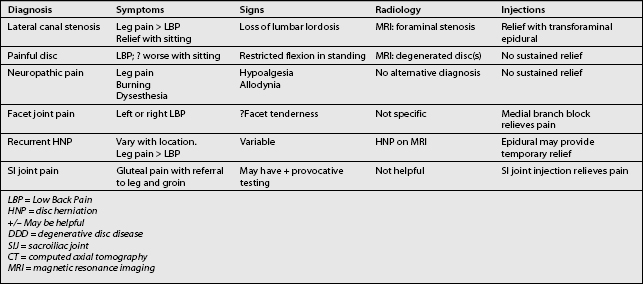

Table 103.2 Differential Diagnosis of Common Causes of FBS by Symptoms, Signs, Radiology, and Injections

Several authors have presented their unquantified impressions and experiences regarding the causes of FBSS. Fritsch et al.6 reviewed 136 patients who had revision surgeries after clinical failure of an initial laminectomy and discectomy, and found a high prevalence of recurrent disc herniations and instability. Kostuik7 reviewed the potential causes of failure of decompression, but provided no quantitative data.

In this chapter, the author has used functional definitions which are a composite of those proposed by the North American Spine Society8 and the International Association for the Study of Pain,9 modified by personal clinical experiences.

Lateral canal stenosis

Lateral canal stenosis was found in 25–29% of FBSS patients in the more recent studies, but was twice that 25 years ago.3–5 The lower prevalence in later studies may be due to better preoperative recognition of the condition and more meticulous decompression.

Lateral canal stenosis usually presents with pain that is predominantly in one leg or buttock region (see Table 103.2). The leg and gluteal pains are usually worsened by standing and walking and improved by sitting. MRI or CT scan must show narrowing of the nerve root lateral canal at the index level or an adjacent segment. Lateral canal stenosis may be characterized as ‘up-down stenosis’ due to loss of disc space height or ‘front-back stenosis’ due to facet hypertrophy and osteophyte formation. There is usually at least temporary relief of leg pain after transforaminal epidural blockade of the suspected nerve root.10,11

Painful discs

One or more painful discs were the cause of FBSS in about 21% of patients.3–5 Painful discs may occur at the index level, adjacent level, and occasionally at the level of a prior posterolateral fusion.11 In the Waguespack study,4 painful discs were responsible for FBSS in 31 (17%) patients who did not have prior fusion and 5 (3%) additional patients had a painful disc at a level contained within a prior solid fusion.

It is clear that discs have the substrate to become painful. They are richly innervated with nerve endings that have the potential to be nociceptive.12,13 In the normal disc, nerve endings are limited to the outer third of the anulus. In the degenerated disc, there is proliferation of nerve endings, and in 40% of severely degenerated discs, the nociceptors have grown inward to reach the nucleus.12

Discogenic pain presents with LBP with or without referred buttock or leg pain (see Table 103.2). Painful discs usually appear desiccated and may be narrowed on MRI scan. Schwarzer et al. found no symptoms or signs that are specific for discogenic pain,14 but there may be a few clues.15 Discogenic pain is usually worsened by sitting and by transition from sitting to standing.15 Pain may be improved somewhat by standing or walking. During examination, pain is usually worsened by flexion during standing, which is also decreased due to pain. There may be tenderness over the spinous processes, but not over the facet joints.

Discography is often used to confirm the clinical impression of discogenic pain. It is controversial in chronic LBP and even more so in patients with FBSS.16–18 In every instance, discography must be interpreted very carefully and only in conjunction with the history, examination, imaging studies, and psychological status of the patient.19 The value of discography at a disc that has had prior surgery is not totally clear, but may be useful when carefully interpreted.13 When the diagnosis of discogenic pain is suggested by history and examination, MRI shows only the one bad disc, and other potential causes of LBP are excluded, there is probably no need to perform discography. If discography is used in the setting of FBSS and probable discogenic pain, it is probably most useful to prove other discs are not involved.

Disc herniation

Recurrent or residual disc herniation occurred 7–12% of patients with FBSS.3–5 In the presence of epidural or perineural fibrosis and a nerve root that is surrounded by scar, a disc herniation may cause more leg pain than expected if there were no fibrosis.

The symptoms of recurrent or residual disc herniation (HNP) depend on its location (see Table 103.2). A midline HNP presents as discogenic LBP. Posterolateral HNP will usually present with a predominance of leg pain in the distribution of a single dermatome, but if the disc is sufficiently damaged internally, there can be a significant amount of low back pain as well. There will be MRI evidence of the disc herniation.

Neuropathic pain

Neuropathic pain was the predominant problem in 9% of the author’s patients.4 Burton et al. observed neuropathic pain in less than 5% of their patients.3 It is not clear if there has been an increase in nerve root injury or an increased recognition of neuropathic pain. Nerve roots can be damaged during surgery, but damage is more likely due to prolonged unrelieved compression by spinal stenosis or disc herniation. The incidence of arachnoiditis may be decreasing, perhaps because oil-based myelography is no longer performed.

Neuropathic pain implies that pain arises from nerve injury or dysfunction. There is a predominance of leg pain, which is usually present in one or two adjacent dermatomes. In classic presentations, the pain is described as burning or dysesthetic, but in neuropathic disorders and FBSS this may not be the case (see Table 103.2). Pain is usually constant but it may be worsened by activity because the damaged nerve is sensitized and minor biomechanical changes may worsen pain. In pure neuropathic pain, there is no evidence of nerve root compression on MRI or CT scan.

Facet syndrome

Pain that arises from the facet joint is responsible for the pain in about 3% of patients with FBSS and 15–30% of patients with chronic LBP.5,20 The facet joint is susceptible to inflammation, damage during surgery, or the mechanical stresses of fusion at a segment below.

There are no data that specifically address the symptoms or signs of facet syndrome in patients with FBSS, but several papers have addressed the problem in chronic LBP.15,20–24 Schwartzer et al. felt there were no symptoms typical for facet joint pain, although the presence of midline LBP was not likely in facet syndrome.21 Others feel there are symptoms that are suggestive (see Table 103.2).22,24 Pain is more likely to be experienced just lateral to the midline and is frequently referred to one or both gluteal regions. Pain is better when the patient is lying supine.22 It is less severe sitting than standing or walking, and pain is not worsened during transition from sitting to standing.25 Examination findings are not specific, but there may be tenderness with palpation directly over the joints but not over the spinous processes, and more pain with extension than flexion while standing.

As discussed elsewhere in this text, the diagnosis of facet joint pain is made by intra-articular infusion of local anesthetic or blockade of the medial branches of the primary dorsal rami that serve the putative painful joint. The preferred treatment is radiofrequency neurotomy (RFN), which is successful in a high percentage of well-selected patients.26–29 RFN generally relieves pain for 9–12 months and then it can be repeated, and Schofferman and Kine have shown that repeated RFN remains effective.29

Sacroiliac joint pain

The sacroiliac joint (SIJ) is responsible for the pain in about 2% of patients with FBSS5 and 15–30% of patients with chronic LBP.30 There are many potential inciting events that may lead to the development of SI joint pain. The joint may become painful after acute or cumulative trauma, but the cause is often not known.31 The SIJ is vulnerable to the mechanical stresses of fusion to the sacrum32 and can be injured during bone graft harvesting for fusion.33

There are no data that have specifically examined the symptoms or signs of sacroiliac joint syndrome in patients with prior surgery, but several papers have addressed the problem in the chronic LBP population.15,30 Schwartzer et al. reported that there were no typical symptoms for SIJ pain.30 Others believe there is a pattern with pain experienced in the gluteal regions distal to the posterior superior iliac crest just off the midline. The patient may point directly over the joint when asked to show where the pain is the worst. Pain is worsened during transition from sitting to standing15 and appears to increase with single leg weight bearing. Examination findings are not specific, but there may be tenderness with palpation directly over the SIJ, and when there are three or four other signs, diagnosis is probable.34

As discussed elsewhere, the diagnosis is made by local anesthetic blockade of the SIJ under fluoroscopic guidance. Treatment is multidimensional. It requires strengthening the gluteal muscles, teaching the patient to self-mobilize the joint, and increasing the flexibility of the gluteal and hamstring muscles. This may be supplemented by spinal manipulative therapy. Therapeutic SIJ injection utilizing glucocorticoid can be helpful.35 Very rarely SIJ fusion is necessary.

Epidural fibrosis

Epidural fibrosis occurs after most, if not all, posterior lumbar decompressive surgeries. Scar forms in patients with good and bad outcomes alike. There is controversy whether fibrosis can cause pain after lumbar surgery in the absence of other structural disorders or neuropathic pain. Some interventional spine specialists believe fibrosis alone can cause pain, but most spine specialists do not. Although it has been established that fibrosis occurs, that fibrosis may alter neural sensitivity, and that fibrosis may make re-operation more difficult, there is no good evidence that perineural fibrosis itself can cause pain or that treatment directed toward only the fibrosis can improve the pain. There is no proven method to determine whether fibrosis might be a cause of pain, only a somewhat circuitous theoretical construct.36 Finally, even if fibrosis were pathological rather than an innocuous bystander, it would be more likely to cause leg pain rather than LBP.

TECHNICAL FAILURE AND COMPLICATIONS

Pseudoarthrosis

Pseudoarthrosis is a failure of fusion (nonunion), and was the predominant problem in 15% of the patients of Waguespack et al. with FBSS who had prior attempted fusion.4 They did not collect sufficient data to establish the number of patients who had undergone an attempted fusion, and therefore it is not possible to know the clinical relevance of this percentage. Some patients with nonunions have pain, but others do not. Therefore, one cannot assume that the nonunion is the cause of the pain. The author likes this summary poem:

If there’s pain and a pseudoarthrosis,

It’s usually a disc or spinal stenosis;

But think of facet joints or SI – they’re closest.

Nerves can be damaged and lose their gliosis

And pains can be worsened by depression or neurosis.

A definitive diagnosis of pseudoarthrosis requires surgical exploration, but radiological findings can be suggestive. Plain radiographs are not reliable to prove fusion is solid, but certainly can be suggestive of nonunion.37 Standing films with sagittal views taken in flexion and extension are useful if there is motion. CT scans that include reformatted curved coronal as well as sagittal and axial images are the most useful test.38 They can visualize the anterior column when there has been attempted interbody fusion (bone or cages), and curved coronal sections extended out to the spinous processes are the best test to visualize the integrity of posterolateral fusions.

After interbody fusion with threaded metal cages, a nonunion may be particularly difficult to diagnose.39 There may be no lucency on plain X-rays, no motion with standing X-rays in flexion versus extension, and no lucency on CT scan, and still pseudoarthrosis may be present. The author has noted that patients who are not significantly improved by 6 months after fusion with threaded interbody cages often benefit from a salvage posterolateral fusion.

PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS IN FAILED BACK SURGERY

Psychological disorders are often invoked when evaluating patients with FBSS. Pure psychogenic pain (pain disorder, psychological type) is rare in patients with FBSS.40 It is more likely that if psychological factors are present they make pain worse rather than cause it. More importantly, if psychological problems are present in a patient with FBSS, it is most likely they were present before surgery and did not just appear afterwards. Psychological issues should always be considered and diagnosed preoperatively. In the author’s opinion, it is not appropriate for a surgeon to invoke a psychological cause of FBSS and, in a sense, ‘blame the patient’ after the surgery.

RADIOLOGICAL EVALUATION OF FAILED BACK SURGERY

Herzog discussed the requirements for imaging patients with FBSS and much of the following section is a summary of his presentation.1,38,41 Radiological examination usually includes X-rays and either MRI or CT scan. Standard radiographs with standing flexion and extension lateral views are used to assess alignment, extent of disc space narrowing, instability, and, when fusion has been attempted, perhaps pseudoarthrosis.36

MRI is the optimal examination for most FBSS patients unless the issue is pseudoarthrosis, in which case CT with multiplanar reformations (CT/MPR) is much better.1,37 MRI should be done using a high-field strength (1.0–1.5 Tesla) scanner for maximum information. With MRI, it is necessary that the study be done to visualize left and right extraforaminal zones so as to avoid missing foraminal or extraforaminal pathology. At least one axial sequence should have contiguous stacked images. Angled T2-weighted sections from T12–L1 to L5–S1 through the disc spaces are done to evaluate the cross-sectional area of the thecal sac, to evaluate the central canal, and to define the exact relationship of the structural changes to all the neural elements. A coronal sequence is useful to see foraminal and extraforaminal herniations.1,40

High-resolution CT/MPR is the optimal study when the integrity of a fusion or the placement of pedicle screws needs assessment.38 It is helpful in a CT examination to perform stacked 1 mm thick sections through the segment containing the cage to detect early loosening or the presence of bridging bone. CT/MPR should employ stacked 2–3 mm sections with sagittal and coronal reformations, and cover several segments proximal and distal to the surgery.

ROLE OF THE HISTORY

Establishing the structural diagnosis

Location of pain

Pain generally flows down hill. LBP in the midline is often discogenic. Pain 1 or 2 cm off the either side of the midline is often of facet origin. Facet pain is not usually limited to the midline.21 Pain in the gluteal regions is not specific, as the buttocks is a watershed area for pain emanating from most structures in the lumbar spine. Pain directly over the sacral sulcus may indicate the SIJ is the source of the pain. SIJ pain often is referred to the ipsilateral groin. Leg pain is not specific unless it follows a dermatomal pattern.

Establishing what went wrong

Technical failure

It is reasonably straightforward to diagnose pseudoarthrosis when there is an interbody fusion with bone. It is very useful, but often overlooked, to get a Furgeson (angled) view of the L5–S1 interspace to look for lucency. CT scan will often reveal the lucency if plain X-rays are not diagnostic. Posterolateral fusion without instrumentation will usually be seen on CT if there are adequate curved coronal sections taken out to the tips of the transverse processes. If there is instrumentation, nonunion may be difficult to see. Occasionally, oblique radiographs are helpful.

Complication

If pedicle screws are misplaced medially through the cortex, there can be leg pain in a single dermatome that corresponds to the breach in the pedicle. CT often will suggest this. Complications such as infection usually occur early in the postoperative period but rarely can occur later.41,42

1 Schofferman J, Reynolds J, Dreyfuss P, et al. Failed back surgery. Spine J. 2003;3:400-403.

2 Farrar JT, Young JP, LaMoreaux L, et al. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149-158.

3 Burton CV, Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Yong-Hing K, et al. Causes of failure of surgery on the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop. 1981;157:191-199.

4 Waguespack A, Schofferman J, Slosar P, et al. Etiology of long-term failures of lumbar spine surgery. Pain Med. 2002;3:18-22.

5 Slipman CW, Shin CH, Patel RK, et al. Etiologies of failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Med. 2002;3:200-214.

6 Fritsch EW, Heisel J, Rupp S. The failed back surgery syndrome. Reasons, intraoperative findings, and long-term results: a report of 182 operative treatments. Spine. 1996;21:626-633.

7 Kostuik JP. The surgical treatment of failures of laminectomy. Spine: state of the art reviews. 1997;11:509-538.

8 Fardon DF, Herzog RJ, Mink JH, et al. Contemporary concepts in spine Care. Nomenclature of lumbar disc disorders. North American Spine Society. May, 1995.

9 Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain, 2nd edn. Seattle: IASP Press, 1994.

10 Slosar PJ, White AH, Wetzel FT. The use of selective nerve root blocks: diagnostic, therapeutic, or placebo? Spine. 1998;20:2253-2256.

11 van Akkerveeken P. The diagnostic value of nerve root sheath infiltration. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:61-63.

12 Freemont A, Peacock T, Goupille P, et al. Nerve ingrowth into diseased intervertebral discs in chronic low back pain. Lancet. 1997;350:178-181.

13 Coppes M, Marani E, Thomeer R, et al. Innervation of ‘painful’ lumbar discs. Spine. 1997;22:2342-2350.

14 Schwarzer A, Aprill C, Derby R, et al. The prevalence and clinical features of internal disc disruption in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:1878-1883.

15 Young S, Aprill C, Laslett M. Correlation of clinical examination characteristics with three sources of chronic low back pain. Spine J. 2003;3:460-465.

16 Walsh TR, Weinstein JN, Spratt KF, et al. Lumbar discography in normal subjects. J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:1081-1088.

17 Derby R, Howard MW, Grant JM, et al. The ability of pressure-controlled discography to predict surgical and nonsurgical outcomes. Spine. 1999;24:364-372.

18 Wetzel FT, LaRocca H, Lowery GL, et al. The treatment of lumbar spinal pain syndromes diagnosed by discography. Lumbar arthrodesis. Spine. 1994;19:792-800.

19 Carragee EJ, Alamin TF. Discography: a review. Spine J. 2001;1:364-372.

20 Barrick W, Schofferman J, Reynolds J, et al. Anterior fusion improves discogenic pain at levels of posterolateral fusion. Spine. 2000;25:853-857.

21 Schwarzer A, Wang S, Bogduk N, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain: A study in an Australian population with chronic low pack pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54:100-106.

22 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, et al. Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the lumbar zygapophyseal joints. Is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity? Spine. 1994;19:1132-1137.

23 Revel M, et al. Capacity of the clinical picture to characterize facet joint pain. Spine. 1998;23:1972-1977.

24 Jackson RP. The facet syndrome: myth or reality? Clin Orthop. 1992;279:110-121.

25 Helbig T, Lee CK. The lumbar facet syndrome. Spine. 1988;13:61-64.

26 Dreyfuss P, Halbrook B, Pauza K, et al. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain. Spine. 2000;25:1270-1277.

27 van Kleef M, Barendse GA, Kessels A, et al. Randomized trial of radiofrequency lumbar facet denervation for chronic low back pain. Spine. 1999;24:1937-1942.

28 Leclaire R, Fortin L, Lambert R, et al. Radiofrequency facet joint denervation in the treatment of low back pain. Spine. 2001;26:1411-1417.

29 Schofferman J, Kine G. The effectiveness of repeated radiofrequency neurotomy for lumbar facet pain. Spine. 2004;29:2471-2473.

30 Schwarzer A, Aprill C, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:31-37.

31 Chou L, Slipman CW, Bhagia SM, et al. Inciting events initiating injection-proven sacroiliac joint syndrome. Pain Med. 2004;5:26-32.

32 Katz V, Schofferman J, Reynolds J. The sacroiliac joint: a potential cause of pain after lumbar fusion. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2003;16:96-99.

33 Ebraheim NA, Elgafy H, Semaan HB. Computed tomographic findings in patients with persistent sacroiliac pain after posterior iliac graft harvesting. Spine. 2000;25:2047-2051.

34 Slipman C, Sterenfeld E, Chou L, et al. The predictive value of provocative sacroiliac joint stress maneuvers in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 1998;79:288-292.

35 Slipman CW, Lipetz JS, Vresilovic EJ, et al. Fluoroscopically guided therapeutic sacroiliac joint injections for sacroiliac joint syndrome. Am J Phys Med Rehab. 2001;80(6):425-432.

36 Schofferman J. Failed back surgery. Response to letter to the editor. Spine J. In press.

37 McAfee P, Boden S, Brantigan J, et al. Symposium: a critical discrepancy – a criteria of successful arthrodesis following interbody spinal fusions. Spine. 2001;26:320-324.

38 Herzog RJ, Marcotte PJ. Imaging corner. Assessment of spinal fusion. Critical evaluation of imaging techniques. Spine. 1996;21:1114-1118.

39 Heithoff K, Mullin W, Holte D, et al. The failure of radiographic detection of pseudoarthrosis in patients with titanium lumbar interbody fusion cages. Presented at the 14th annual meeting, North American Spine Society. Chicago, IL; 1999.

40 Polatin PB, Kinney RK, Gatchel RJ, et al. Psychiatric illness and chronic low-back pain. The mind and the spine – which goes first? Spine. 1993;18:66-71.

41 Herzog R. Radiological studies in failed back surgery. Presented at the 18th annual meeting, North American Spine Society. Montreal, Canada. October; 2002.

42 Schofferman L, Schofferman J, Zucherman J, et al. Occult infections as a cause of low-back pain and failed back surgery. Spine. 1989;14:417-419.