16 Faecal incontinence (leakage of stool)

Case

Mrs C.B. is a 58-year-old woman who presents complaining of worsening faecal incontinence over 2 years. She had noticed soiling of her underclothes two or three times per week and needed to wear a pad. This occurred particularly if the stool was loose but also occasionally with formed stool. She also had incontinence to flatus. The incontinence took the form of urgency, with inability to defer defecation and soiling if she did not make the toilet in time. At other times there was involuntary seepage without awareness.

Definitions

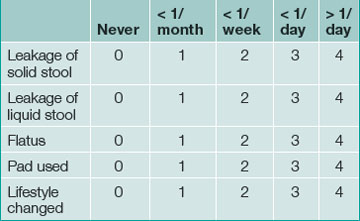

Continence is defined as the ability to control the onset of rectal evacuation. Minor incontinence refers to mucus discharge or incontinence of liquid or solid stool less than once per week. Major incontinence is loss of liquid or solid stool more than once a week, or sufficiently frequently to be causing social embarrassment for the patient. A more objective numerical continence scoring system, taking into account the exact frequency and nature of incontinence, is now commonly used in specialist centres and a simplified version is helpful for routine clinical assessment (Table 16.1).

History

The causes of faecal incontinence are summarised in Box 16.1. A good history about the nature of the incontinence will often provide clues about the cause. Physical examination and tests of anorectal function will determine whether the sphincter is normal, and will identify the likely pathology in most cases. The three most common causes of faecal incontinence requiring surgical treatment are rectal prolapse, sphincter trauma and neurogenic incontinence. These conditions account for the majority of patients who suffer severe longstanding symptoms.

The features in the history that need to be established in these patients are:

Examination

The patient is examined in the left lateral position with the hips flexed to allow the examiner good access to the perineum and anal region. The area is inspected for soiling, and for excoriation of the perianal skin as evidence of chronic irritation secondary to incontinence. Any external prolapse at the anus (Box 16.2) and an asymmetrical sphincter caused by trauma and perianal scarring are looked for.

Digital anorectal examination is carried out next and the resting tone (produced by the internal sphincter) is noted. The functional length of the anal canal in centimetres should be estimated. The strength of the pelvic floor muscles is assessed by pressing posteriorly and laterally. External sphincter strength is assessed by asking the patient to contract the sphincter and, thereafter, to cough. A shortened, weak sphincter is found in neurogenic incontinence. A weak sphincter of normal length is caused by a sphincter defect due to trauma. The sphincter is examined circumferentially between the thumb and index finger and a defect may be palpable.

Proctoscopy and sigmoidoscopy

At proctoscopy, anal mucosal prolapse and haemorrhoids can be diagnosed. Sigmoidoscopy is essential to exclude rectal pathology including proctitis and rectal tumours (Ch 22). The patient is asked to strain down on the sigmoidoscope and prolapse of the rectal wall can often be detected in this way.

Physiological Anorectal Assessment

Physiology of continence

Normal continence depends on an interaction of the following factors.

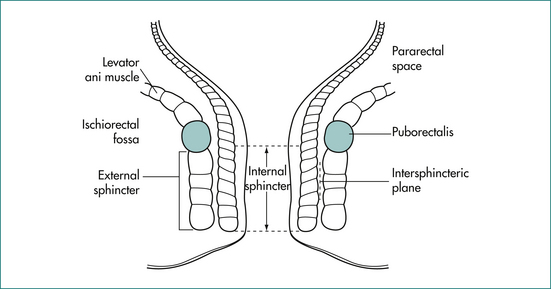

The anal canal is surrounded by a muscular tube that produces a high-pressure zone exceeding the pressure in the rectum. The sphincter contains two layers (Fig 16.1): an inner layer of involuntary smooth muscle (internal sphincter) and an outer layer of skeletal muscle (external sphincter). The internal sphincter is a distal continuation of the circular muscle of the rectum and is in a state of constant contraction, maintained by a process of intrinsic muscle stimulation. Relaxation of the muscle occurs during defecation, mediated by a local neural reflex within the wall of the anorectum in response to distension of the rectum by the faecal bolus, as well as by extrinsic autonomic control via the presacral sympathetic nerves. The external sphincter is under voluntary control but also contracts involuntarily in response to an increase in intraabdominal pressure via a spinal reflex through the anterior horns of the S2–S4 spinal segments and the Onuf nucleus in the spinal cord.

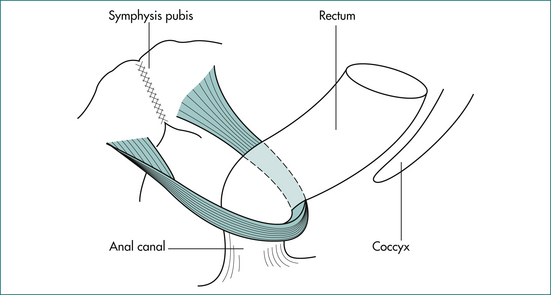

The puborectalis muscle lies immediately above the external sphincter and forms a muscular sling behind the anus (Fig 16.2). It supports the anus and produces the anorectal angle, which is felt posteriorly at the upper end of the anal canal when doing a rectal examination.

Figure 16.2 The puborectalis muscle forms a sling behind the junction of the anus and rectum.

From Anderson JE, ed. Grant’s Atlas. 7th edn. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1978, with permission from the publisher.

The anal mucosa contains an abundance of sensory nerve endings. Spontaneous relaxation of the upper part of the internal sphincter occurs intermittently to allow the anal mucosa to ‘sample’ the contents of the rectum (the sampling reflex). This allows us to normally distinguish flatus from stool in the rectum.

Diagnostic tests

Anorectal manometry

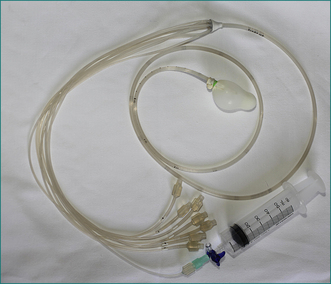

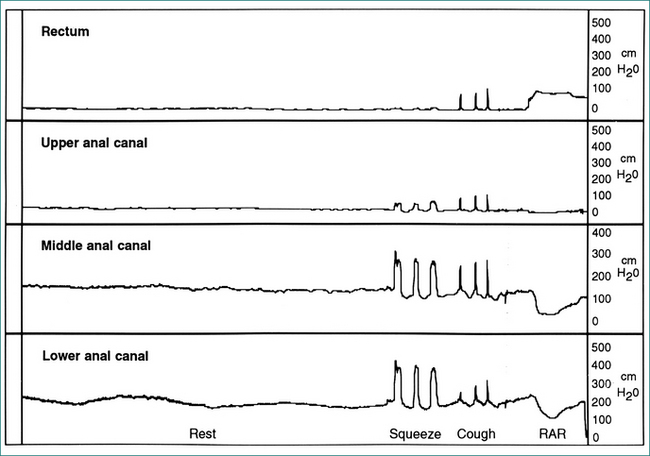

Pressure in the anus and rectum is measured using a narrow diameter multichannel catheter. Each channel is perfused with water and connected to a pressure transducer and digital recording apparatus; sequential channels open at 0.75 cm intervals from the tip of the catheter (Fig 16.3). The pressure at rest reflects the strength of the internal sphincter, and pressure during voluntary contraction of the muscles is a measure of the external sphincter strength (Fig 16.4). Relaxation of the internal sphincter is tested by inflating a balloon positioned in the rectum at the tip of the manometry catheter, while recording anal pressure. Manometry is a very useful test because it defines which muscle is affected in a patient with sphincter weakness. It also demonstrates that sphincter function is normal in a patient whose incontinence is due to diarrhoea or excessive colonic propulsion, or due to a local anal condition such as haemorrhoids and, hence, confirms that sphincter weakness is not the cause of the incontinence.

Electrophysiology

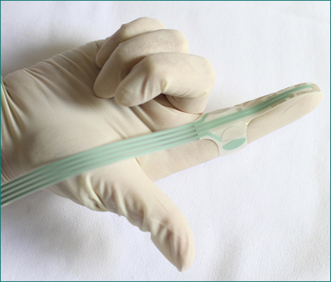

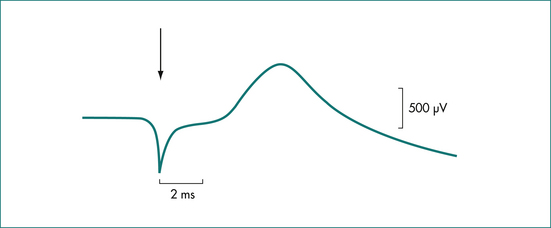

In patients with suspected neurogenic incontinence the function of the pudendal nerves is tested. Motor conduction is measured by transrectal stimulation of the nerves, using a fine disposable electrode mounted on the gloved index finger (Fig 16.5). The left and right pudendal nerves are stimulated at the point that each passes around the ischial spine and the conduction time to the external anal sphincter is recorded (Fig 16.6). Stretch-induced damage to the nerves caused by difficult vaginal delivery or chronic excessive straining at stool is reflected in the slowing of conduction in the nerves due to axonal degeneration. Sensory conduction is measured by delivering a small current to the anal mucosa. The current is increased in fractions of a milliamp until a slight, painless, tapping feeling is reported by the patient, and the threshold of stimulation is measured. With pudendal nerve damage there is loss of sensation, reflected as an increased threshold of stimulation.

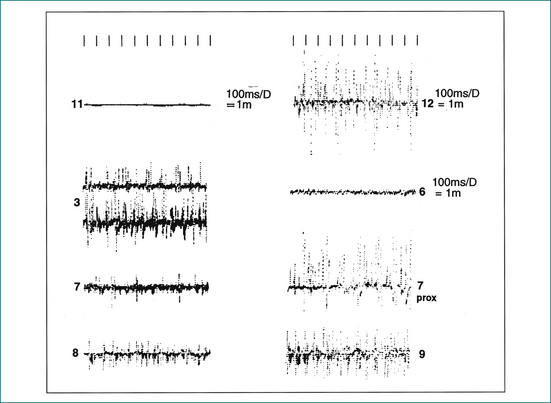

Electromyography is carried out using a fine needle electrode inserted into the external sphincter muscle. Muscle contraction is amplified and displayed as spikes of electrical activity. Normal muscle activity can be clearly distinguished from non-functional scar tissue, allowing the site and extent of a sphincter defect to be clearly defined (Fig 16.7). Electromyography is used less commonly, with the advent of endoanal ultrasound.

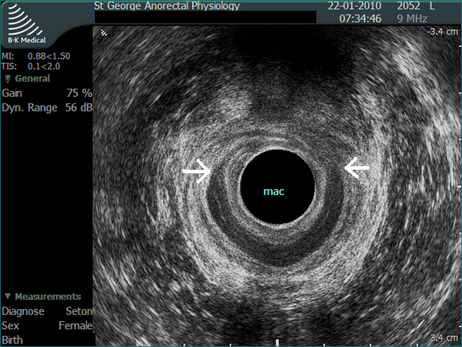

Ultrasound

Endoanal ultrasound has become a valuable tool to study anal function. It is very accurate in identifying a defect in the internal or external sphincter, and is less invasive than electromyography. The ultrasound probe records through 360° to give a complete image of the sphincter (Figs 16.8 and 16.9).

Proctography

Barium studies of the anorectum are used to test the ability of the anal sphincter to maintain continence. Semisolid barium paste of similar consistency to soft stool is instilled into the rectum. Lateral x-ray examination is made of the rectum and anus while the patient coughs, moves and during a Valsalva manoeuvre, and the amount of leakage is assessed (Fig 16.10). This examination is used to confirm the diagnosis of neurogenic incontinence.

Conditions Causing Incontinence with a Normal Sphincter

Diarrhoea

Aetiology

Diarrhoea, either acute or chronic, may overcome the ability of the normal sphincter to resist the forceful passage of liquid stool. High pressures generated in the colon may exceed the maximum pressure of the anal sphincter, and incontinence is then inevitable. Incontinence may even occur when stool consistency and frequency are normal, due to sudden excessive colonic propulsion.

Clinical features

In patients with diarrhoea, incontinence is sometimes preceded by lower abdominal pain or a sudden urgent call to stool. Other clinical features are discussed in Chapters 13 and 14.

Treatment

When there is a colonic cause for incontinence, simple antidiarrhoeal medication may produce a very dramatic improvement in some patients. Chronic diarrhoea should be investigated with fresh stool specimens sent for microscopy and culture, and with sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. Special tests for malabsorption or more rare causes of diarrhoea (see Ch 14) will be indicated in some cases.

Anorectal conditions

In older patients with a short history of incontinence, conditions to consider include rectal cancer (Ch 22), inflammatory bowel disease (Ch 15) and ischaemic proctitis (Ch 4).

Treatment

With a normal sphincter, treatment, if successful, will result in the return of normal continence. Rectal cancer presenting with incontinence is treated by surgery according to conventional principles (Ch 22). Prolapsing haemorrhoids and anal mucosal prolapse causing incontinence usually require rubber-band ligation (Ch 12). Occasionally when the prolapse is large, surgical excision is required. Anal fissure causing incontinence is always a deep chronic fissure, which should be treated surgically by lateral sphincterotomy. Abnormalities in rectal sensation may respond to loperamide because of the constipating effect of the drug.

Conditions Causing Incontinence with an Abnormal Sphincter

Anal sepsis

Perianal sepsis may be severe enough to result in sphincter destruction and incontinence (Ch 12). Complex anal fistulae with longstanding sepsis and hidradenitis suppurativa (infection in perianal apocrine glands) are the most common causes.

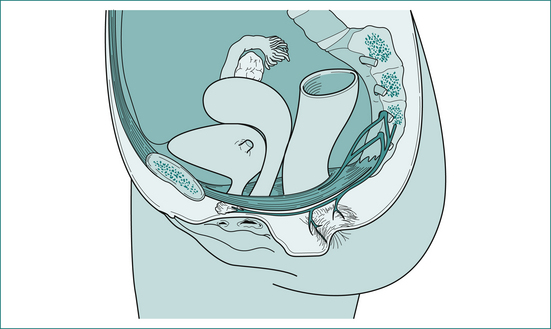

Rectal prolapse

Rectal prolapse is a circumferential intussusception of the rectum, which passes through the anal sphincter and beyond the anal verge to the exterior (Fig 16.11). It occurs in females in 90% of cases. In over two-thirds of patients there is associated neurogenic weakness of the anal sphincter (see neurogenic incontinence), but unlike patients with neurogenic incontinence, where almost all are multiparous women, almost half the women with rectal prolapse are nulliparous.

Clinical features

The condition is most common over the age of 50 years, and a smaller number of patients are in the 20–50-year age group. It occasionally occurs in children.

Sphincter trauma

Aetiology

Direct trauma to the sphincter is most commonly due to an obstetric tear, or damage resulting from surgery for anal fistula. Other less common causes are impalement on a sharp object, pelvic fracture, stab wound or gunshot wound.

Neurogenic incontinence

Aetiology

The nerve supply to the external anal sphincter is via the pudendal nerve (arising from S2–S4 sacral segments). The puborectalis and levator ani (pubococcygeus) muscles are supplied by direct branches from the sacral nerve plexus (S3, S4) (Fig 16.12). During vaginal delivery there is marked descent of the pelvic floor with stretching of the pudendal and sacral nerves, and a temporary reversible nerve injury occurs in some cases. Somatic nerves can normally withstand a stretch injury of up to 12% of their length and it has been calculated that stretching of 20% may occur during vaginal delivery. In the majority of cases, the neuropraxia resolves over a 6-week period, but a permanent injury remains in others. This may not result in muscle weakness immediately, but as the pelvic floor muscles age, particularly after menopause, a cumulative weakness develops, leading to incontinence.

Treatment

Initial treatment is with stool bulking agents such as psyllium, in combination with loperamide (Imodium™), which firms the stool and also directly stimulates the internal anal sphincter. Biofeedback may be used, where the patient is taught to contract the external sphincter muscle more effectively by showing the patient sphincter pressure measurements during physiotherapy exercises.

If all measures fail and incontinence is severe, formation of a stoma may be offered.

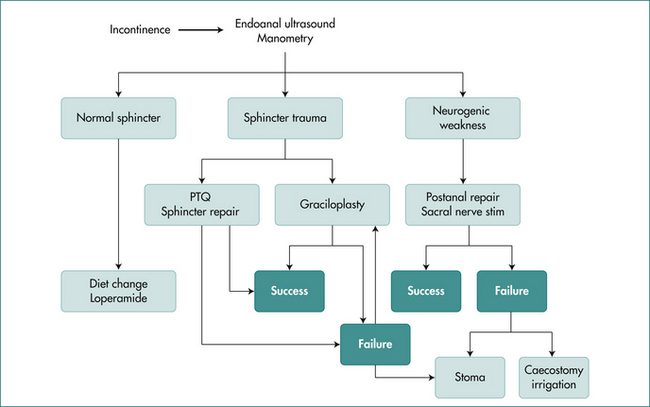

The treatment of faecal incontinence has multiple options, and treatment must be based on a sound clinical history and examination, assisted by tests of anorectal physiology. An algorithm for treatment is shown in Figure 16.13.

Key Points

History

Examination

Investigations

Management

Bartlett L., Ho Y.H. PTQ™ anal implants for the treatment of faecal incontinence. Br J Surg. 2009;96:1468-1475.

Jarrett M.E., Varma J.S., Duthie, et al. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence in the UK. Br J Surg. 2004;91:955-961.

Keighley M.R.B., Williams N.S. Faecal incontinence. In: Keighley M.R.B., Williams N.S., editors. Surgery of the anus, rectum and colon. 3nd edn. London: WB Saunders; 2008:591-692.

Leung F.W., Rao S.S.C. Fecal incontinence in the elderly. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2009;38:503-511.

Madoff R.D., Parker S.C., Varma M.G., et al. Faecal incontinence in adults. Lancet. 2004;364:621-632.

Mander B.J., Wexner M.L., Williams N.S., et al. Results of a multicentre trial of the electrically stimulated gracilis neoanal sphincter. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1543-1548.

Norton C., Chelvanayagam S., Wilson-Barnett J., et al. Randomized controlled trial of biofeedback for fecal incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1320-1329.