Facilitating Airway Clearance with Coughing Techniques

Cough is one of the most frequently reported symptoms in patients with pulmonary impairments. It is important to get a good history and physical examination to determine the cause and course of the patient’s cough.1 History should include sudden onset versus chronic; duration and type of cough—productive, nonproductive, or wheezy; whether the cough disturbs sleep and function; and what relieves or aggravates it. Diagnostic testing may include chest imaging, pulmonary function tests, bronchoscopy, and evaluation for gastroesophageal reflux (GER).2 GER is said to be the causative factor in up to 41% of adults with chronic cough.3

Frequent coughing or throat clearing may signal that the airways are irritated, that mucus is not clearing normally, or that the person is in an uncomfortable situation. This is something to be aware of, especially when treating patients with cystic fibrosis or asthma and patients with psychogenic issues. Depending on the reason for a cough, a variety of different approaches might be utilized. In most patients with primary pulmonary disease, the cough is related to the need for improved hydration and airway clearance. With patients who have psychogenic coughs, psychotherapy, biofeedback, and relaxation techniques have proven to be effective.4 Medications to suppress a cough are used rarely, primarily in the case of nonproductive, inflamed airways. Future directions are moving toward better medical management of cough reflex hypersensitivity through better diagnosis and medication.5 If the cough is productive, hydration and coughing are necessary to expel secretions to prevent pneumonia from occurring.

Frequent coughing or throat clearing may indicate other problems besides airway clearance deficits. For example, a patient may have postnasal drip from a sinus infection or allergy. When the mucus drips down into the back of the throat, it can cause a reflex cough to clear it. Other causes include bronchogenic carcinoma, nervousness, and smoking. Many over-the-counter products are marketed to improve environmental air factors, but there has been conflicting evidence for their effectivess.6

In a pediatric patient with a cough, a foreign body or object inserted or inspired into the nose or airway should be ruled out. Gastroesophageal reflux must be evaluated in children and adults with symptoms of cough.7,8 GER is often overlooked in children. For example, if a child is beginning to prop-sit and pushes back to get out of that posture regularly, it may be because of GER irritation. This can delay developmental postures, so it is an important consideration for pediatric therapists.

A persistent cough or throat clearing might be indicative of asthma or other pulmonary diseases, but it may also be a result of GER and irritation to the upper airway. It is important to ask questions related to the patient’s sleep. For example, does the person have heartburn or belching at least once a week after going to bed? Is there breathlessness at rest and nocturnal breathlessness? In a random group study in a large population of young adults, 4% were found to have GER. People with asthma and GER (9% of asthmatics had GER) had more nocturnal cough and morning phlegm with sleep-related symptoms.9 The authors concluded that there was a strong association between asthma and GER.

Many patients with asthma find cough to be a more irritating, difficult symptom than wheezing and secretions. Yet cough is often not taken as seriously, even though it can be a life-interrupting symptom. Night cough can be a particularly difficult symptom in people with asthma and will make sleep difficult.10 Persistent cough has also been reported following pulmonary resection. The cause seems to be unclear, but some studies have focused on the population of patients who have had a lobectomy and mediastinal lymph node resection, some of whom also had GER. These were at increased risk for continued cough, which was found to persist up to a year later. Of this group, 90% saw improvement in their coughing with medication.11

If a patient demonstrates retained secretions on radiography, encourage hydration (drinking water), use airway clearance mobilization techniques, and carefully evaluate the cough. Instruct the patient in controlled coughing when mucus is felt in the throat or upper airways (see Chapter 21).

Cough Associated with Eating or Drinking

If a cough is associated with eating, drinking, or taking medications, the patient’s swallowing mechanism should be examined and evaluated. A barium swallow (“cookie swallow”) is a fluoroscopic study in which the patient is given an opaque liquid, and a moving picture is observed to determine whether there is aspiration into the trachea. Populations commonly in need of evaluation of swallowing are patients with neurological disorders, such as those that occur with cerebrovascular accident (CVA), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), cerebral palsy, Parkinson disease, and multiple sclerosis (MS). Patients who have tracheostomy tubes may experience difficulty in swallowing because the tube inhibits the normal movement of the larynx during swallowing. The use of a Passey-Muir valve has been found to be clinically effective in restoring a more normal swallow in patients with a tracheostomy. Older adults with chronic cough should be carefully observed and monitored, because the chronic cough may be a defense mechanism to prevent aspiration.12 This is especially true if there are comorbidities such as a previous stroke. This list is not exhaustive; any patient who chokes when you offer fluids or who reports to you that food or water “goes down the wrong way” should be referred for evaluation of the swallowing mechanism.

Complications of Coughing

Patients with chronic cough can also experience stress urinary incontinence (SUI).13 This is often not reported to the therapist or physician because the patient is embarrassed or considers this a problem of aging rather than a condition related to the chronic cough. Such patients often do not realize that physical therapy treatment is available for SUI. This knowledge deficit has been found in adolescents and teenagers with cystic fibrosis, as well as in adults with COPD. Asking patients with chronic cough about SUI should be a part of the routine examination and evaluation. Making a referral to a pelvic floor therapist can make a difference in their quality of life as SUI is managed.

Stages of Cough

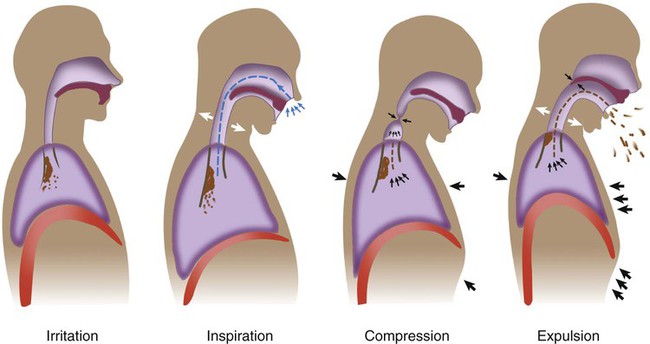

Four stages are involved in producing an effective cough.14 The first stage requires inspiring enough air to provide the volume necessary for a forceful cough. Generally, adequate inspiratory volumes for a cough are noted to be at least 60% of the predicted vital capacity for that individual. The second stage involves the closing of the glottis (vocal folds) to prepare for the abdominal and intercostal muscles to produce positive intrathoracic pressure distal to the glottis. The third stage is the active contraction of these muscles. The fourth and final stage involves opening of the glottis and the forceful expulsion of the air. The patient usually is able to cough three to six times per expiratory effort. A minimal threshold of FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in 1 second) of at least 60% of the patient’s actual vital capacity is a good indicator of adequate muscle strength necessary for effective expulsion (Figure 22-1). Bach and Saporito (1996)15 established a minimal peak cough flow rate (PCFR) of 160 L/min to effectively clear secretions and to predict successful decannulation for patients with neuromuscular conditions. The use of a simple peak flow meter can help assess the cough. Drops in peak flow have been correlated in children, patients with spinal cord injury, and older adults who have a decreased ability to cough. Assessing PCFR is a simple clinical test that can objectively measure the patient’s ability to provide the exhalation phase of the cough.16–18 During a cough, alveolar, pleural, and subglottal pressures may rise as much as 200 cm H2O.14,19,20

Cough Evaluation

1. Do not disregard posture. Rather than simply asking the patient to cough from whatever position he or she happens to be in, ask instead, “What position do you like to be in when you feel the need to cough?” Then ask the patient to assume that posture, or assist the patient in assuming a posture as close to the preferred posture as possible. Pay close attention to the patient’s choice. A patient should spontaneously choose a posture that lends itself to trunk flexion, which is necessary for effective expulsion and airway protection. A red flag, or inappropriate choice, would be a preference for coughing while supine, which involves the opposite: trunk extension and poor mechanical alignment for airway protection.

2. Now the patient is ready to demonstrate coughing. Do not make the mistake of asking a patient to “show me a cough” or he or she may simply “show you” a cough. It may not be the way the patient coughs to clear secretions. Instead, continue to set the patient up for success by asking him or her, “Can you show me how you would cough if you had secretions in your chest and you felt the need to cough them out?” With these instructions, you are asking the patient to show you something functional rather than theoretical.

Cough effectiveness can now be assessed (Box 22-1). Guidelines for objective evaluation with pulmonary function tests have been indicated previously. This section focuses on analyzing the movement patterns during all four stages of a cough. An effective cough should maximize the function of each individual stage. Thus in most patients (other than those with COPD or asthma), the clinician should see a deep inspiratory effort paired with trunk extension, a momentary hold, and then a strong cough or series of expiratory coughs on a single breath while the patient moves into trunk flexion.

Stage 1: Adequate Inspiration

Did the patient spontaneously inspire a deep breath before coughing, or did he or she cough regardless of the inspiration or expiration cycle? Did the patient spontaneously use trunk extension, an upward eye gaze, or the arms to augment the inspiratory effort? Did the patient take enough time to inspire fully before coughing? If the patient inspires adequately, he or she should be able to sustain two to six coughs per expiratory effort for a cascade effect. Neurologically impaired patients who have inadequate inspiratory efforts usually present with only one or two coughs per breath and generally produce a quieter cough.21 If the patient cannot cough on demand (such as a young child or patient with cognitive impairment), ask the caretaker whether he or she has observed and/or heard the patient’s inspiratory breath and hold before a cough. If so, how effective did the patient’s process seem?

Patient Instruction

Patients with Neuromuscular Weakness or Paralysis

For patients with transient or permanent neuromuscular weakness or paralysis, further instructions may be necessary.20,22–25 These patients must use every physical trait to maximize the function of each stage of the cough (see Figure 22-1). Physically assisting these patients during the expulsion stage of the cough addresses only one aspect.26,27 Care must be taken to look at all four stages to maximize the airway clearance potential of any assistive cough technique. First, the patient must be positioned for success (stage 1). The beginning of any cough requires trunk extension or inspiratory movement to maximize inhalation, whereas the expulsion stage requires trunk flexion or expiratory movement to maximize exhalation.28 Thus for any given posture, the clinician must assess the following:

Whether the posture allows for both trunk movements

Whether flexion and extension are possible, which movement is more important for that particular patient, and whether that posture facilitates its occurrence

How gravity is affecting the patient’s muscle strength and function in that posture

Whether the patient can still protect the airway in this posture

“Look upward while you inhale.”

“Look upward while you inhale.”

“Raise both of your arms up over your head as high as you can while you inhale.”

“Raise both of your arms up over your head as high as you can while you inhale.”

For patients with more limited arm function, apply appropriate ventilatory strategies detailed in Chapter 23. Very subtle movements can then be requested, such as the following:

Although less dramatic than the larger movements described previously, these subtle motions may significantly increase the patient’s inspiratory effort and provide a more active means for the patient to participate in his or her own coughing program.29

“Pull both of your arms down to your hips as you cough.”

“Pull both of your arms down to your hips as you cough.”

Likewise, patients with more limited arm function can be asked to do the following:

“Squeeze your arms to your chest while coughing.”

“Squeeze your arms to your chest while coughing.”

Encourage maximal intrathoracic and intraabdominal pressures

Encourage maximal intrathoracic and intraabdominal pressures

Instruct the patient in appropriate timing and trunk movements for expulsion

Instruct the patient in appropriate timing and trunk movements for expulsion

Objective and subjective assessments can confirm the improvement. However, even with excellent instructions, many patients with neurological disorders require a clinician’s physical assistance to inhale more deeply or to exhale more forcefully because of muscle weakness or paralysis.30

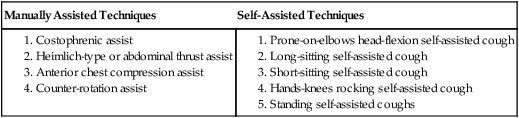

Active Assisted Cough Techniques

If, after instruction and modification in the patient’s cough, the patient still cannot produce an effective cough, then one of the following assistive cough techniques may be appropriate. However, a patient who needs some assistance to improve a cough is not excused from taking an active role in coughing. Keep the coughing process as active as possible for each patient, whether that is accomplished by adding a few verbal cues to improve overall timing or posture while the patient independently performs the cough, or whether it is accomplished by adding eye gazes for a very weak patient who cannot move the upper extremities and breathes with the assistance of a ventilator. Encourage the patient to be responsible for his or her own care by teaching the concepts involved in producing an effective cough.31 In that manner, you will help the patient develop the problem-solving skills necessary for later modifications. Incorporate the guidelines and principles presented thus far with the specific cough techniques that follow. See Box 22-2 for a review of the techniques presented in this chapter.

Breath Stacking and Manual Chest Compression

In a study of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, variations of breath stacking with a manual self-inflating bag were tested. One group simply used the self-inflating bag for breath stacking, whereas the other group used a combined technique of breath stacking with the bag plus manual compression for the exhalation. The combination technique proved to be most effective as measured by peak cough flow (see Figure 21-5).32

Manually Assisted Techniques

Costophrenic Assist

The first assistive cough technique, the costophrenic assist, can be used in any posture. After assessing the most appropriate position for the patient (most often sitting or side-lying) and giving the patient instructions for maximizing all four coughing stages, the therapist places his or her hands on the costophrenic angles of the rib cage (Figure 22-2). At the end of the patient’s next exhalation, the therapist applies a quick manual stretch down and in toward the patient’s navel to facilitate a stronger diaphragmatic and intercostal muscle contraction during the succeeding inhalation. The therapist can also apply a series of repeated contractions based on proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (the PNF approach33) throughout inspiration to facilitate maximal inhalation. The patient may assist the maneuver by actively using his or her upper extremities, head and neck, eyes, trunk, or all of the above to maximize the inspiratory phase. The patient is then asked to “hold it.” Just a moment before asking the patient to actively cough, the therapist applies strong pressure with his or her hands, again down and in toward the navel. In this manner the therapist is assisting both the build-up of intrathoracic pressure and the force of expiration. Of course, the patient should also actively participate by using his or her arms, trunk, or other body parts throughout the entire procedure (see Chapter 23).

This technique’s obvious use would be for patients with weak or paralyzed intercostal or abdominal muscles. The therapist must remember to evaluate the effect of gravity and posture in each position for the appropriateness of this technique.34 This technique is easy to learn and teach and can usually be used from the acute phase through the patient’s rehabilitation phase, thus accounting for its popularity.

Heimlich-Type (or Abdominal Thrust) Assist

The second technique is the Heimlich-type assist, also known as the abdominal thrust assist. This method requires the therapist to place the heel of his or her hand at about the level of the patient’s navel, taking care to avoid direct placement on the lower ribs (Figure 22-3). After appropriate positioning, the patient is instructed to “take in a deep breath and hold it.” The therapist can then facilitate the inspiration. As the patient is instructed to cough, the therapist quickly pushes up and in, under the diaphragm with the heel of his or her hand, as in a Heimlich maneuver. The patient is instructed to assist with appropriate trunk movements as much as possible. Technically, this procedure is very effective at forcefully expelling the air,22 as in a cough, but it can be extremely uncomfortable for the patient for several reasons:

Anterior Chest Compression Assist

The third assistive cough technique is called the anterior chest compression assist because it compresses both the upper and lower anterior chest during the coughing maneuver. This is the first single technique thus far to address the compression needs of the upper and lower chest in one maneuver. The therapist puts one arm across the patient’s pectoralis region to compress the upper chest; the other arm is placed parallel on the lower chest (avoiding the xiphoid process) or on the abdomen (Figure 22-4, A) or is placed as in the Heimlich-type maneuver (Figure 22-4, B). The commands are the same as in the other techniques. Because of the direct manual contact on the chest, inspiration can be easily facilitated first, followed by a “hold.” Thus the therapist can readily enhance the first two cough stages. The therapist then applies a quick force with both arms to simulate the force necessary during the expulsion phase. The directions of the force are:

When performed together, the compression force exerted by both arms forms the letter V.

Counter-Rotation Assist

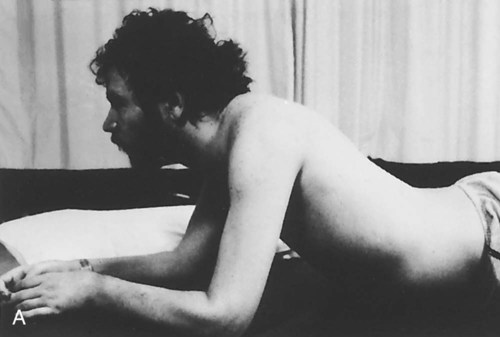

In these authors’ clinical experience, the most effective assistive-cough technique for the widest cross-section of patients with neurological disorders is the fourth and final method described: the side-lying counter-rotation assist.18 The positioning and procedures required for the counter-rotation technique (described in detail in Chapter 23) apply for both the patient and the therapist (Figure 22-5). The therapist should recall that orthopedic precautions for the spine, rib cage, shoulder, and pelvis also apply for this technique.

The therapist begins by following the patient’s breathing cycle, with his or her hands positioned over the patient’s shoulder and pelvis (see Figure 22-5). The therapist then gently assists the patient in inhalation and exhalation to promote better overall ventilation. This sequence is generally repeated for three to five cycles or until the patient appears to have achieved good ventilation to all lung segments.

At this point, the patient is ready to begin the coughing phase of the procedure. The patient is asked to take in as deep a breath as possible, with the therapist assisting the patient in chest expansion (see Figure 22-5, B). Next, the therapist instructs the patient to “hold it” at the end of maximal inspiration. The patient is then commanded to cough out as hard as possible while the therapist quickly and forcefully compresses the chest with his or her hands in their flexion phase positions (see Figure 22-5, A).

1. The rotation component is a natural inhibitor of high tone. Thus this is the least likely of all techniques discussed so far to elicit an increase in abnormal tone during the coughing phase. In fact, the opposite usually occurs. Gentle rotation before passive coughing in a patient who is comatose can reduce high tone and frequently reduces a high respiratory rate. Both of these reduce the possibility of the patient’s keeping his or her glottis closed during the expulsion phase.

2. Counter-rotation is an excellent mobilizer for a tight chest, which in itself can facilitate spontaneous deeper breaths. Tidal volumes (TVs) can therefore be increased for many patients by mobilizing the chest walls.

3. Finally, rotation can be a vestibular stimulator and may assist in arousing the patient cognitively, allowing him or her to take a more active role in the procedure.

Self-Assisted Techniques

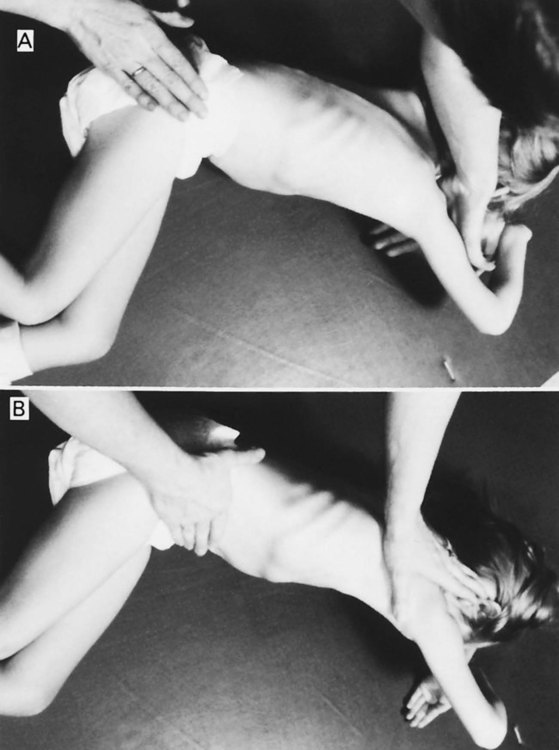

Prone-on-Elbows, Head-Flexion Self-Assisted Cough

The head-flexion assist requires good use of head and neck musculature, seen in patients who have sustained a spinal level injury below C4 (e.g., spinal cord injuries [SCIs], spina bifida). It can be used either as a self-assisted or a therapist-assisted procedure, using the principles of trunk extension to facilitate inspiration and trunk flexion to facilitate expiration. With the patient prone on elbows, the therapist instructs him or her to bring the head and neck up and back as far as possible, inhaling maximally (Figure 22-6, A). The patient is then instructed to cough out as hard as possible while throwing the head forward and down (Figure 22-6, B). This head-and-neck pattern can initially be assisted by the therapist to establish the desired movement pattern and gradually progressed to a resisted pattern to promote increased accessory muscle participation and to strengthen those muscle groups.

Long-Sitting Self-Assisted Cough

There are two variations of this technique, one for tetraplegic patients and one for those who are paraplegic. For the tetraplegic version of the long-sitting self-assist, the patient is positioned on a mat in a long-sitting posture (legs straight out in front) and with upper extremity support. The therapist instructs the patient to extend his or her body backwards while inhaling maximally (Figure 22-7, A). The therapist then tells the patient to cough as the patient moves his or her upper body forward into a completely flexed posture, using shoulder internal rotation if possible (Figure 22-7, B). Once again, the extension aspect of the procedure is used to maximize inhalation, whereas the flexion aspect is used to maximize expiration. The self-directed chest compression occurs mainly on the superior-inferior plane of ventilation only.

The second procedure, the paraplegic version of the long-sit assist, uses the same principles as those described for the tetraplegic patient. However, paraplegic patients have active spinal extension musculature and can achieve greater trunk extension and flexion safely, thus achieving greater chest expansion before the cough and greater chest compression on a superior-inferior plane during the cough. The patient positions his or her upper extremities in a butterfly position or uses elbow retraction, depending on the level of injury (Figure 22-8, A). During the flexion phase, patients throw themselves onto their legs, thereby compressing both the upper and lower chest (Figure 22-8, B). This can be taught very successfully to patients with paraplegia, provided they have adequate trunk balance control. If the patient lacks hip flexion or is worried about bony contact or skin injury, place a pillow (or two as needed) on the legs. This will limit the hip flexion and minimize trauma from the quick thrust onto the legs.

Short-Sitting Self-Assisted Cough

A third assistive cough technique can be done with the patient sitting. The short-sitting self-assist is typically performed in a wheelchair or over the edge of a bed. The patient is instructed to place one hand over the other at the wrist and place them in his or her lap. As in the previous technique, the patient is then asked to extend the trunk backwards while inhaling maximally, followed by a strong voluntary cough. During the cough, the patient pulls his or her hands up and under the diaphragm, resembling the motion of a Heimlich maneuver (Figure 22-9). The hands mimic the abdominal muscles, which would ordinarily contract to push the intestinal contents up and under the diaphragm to aid its recoil ability. This short-sitting technique uses the diaphragm more substantially than the long-sitting procedure and is therefore generally more effective as an assistive cough. It is an effective self-assisted method for patients who have weak diaphragms or abdominal musculature. Most patients with SCI or spina bifida at C5 or below can learn this technique successfully. Patients with tetraplegia usually require trunk support and/or a seat belt from their wheelchairs to perform it independently and safely, whereas most patients with lower-level lesions resulting in paraplegia can perform it from an unsupported short-sitting position. Patients who lack good upper extremity coordination, such as many patients with Parkinson disease and multiple sclerosis (MS), cannot perform the procedure quickly or forcefully enough to make it effective and usually require assistance from another person.

Variations on all sitting techniques can be made readily. Clinicians are encouraged to use the concepts explained in the introduction to these cough techniques to develop techniques that work for their patients. For example, ask a patient in a wheelchair to lift his or her arms up while inhaling, hold, and then cough while throwing the arms down toward the feet or lap using maximum trunk flexion (use a seat belt for safety). Another idea is to have the patient hook one arm on a push handle of the wheelchair and move the other arm up and back (as in a pattern of shoulder flexion, abduction, and external rotation proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation [PNF Pattern D2]);35 make sure the patient’s moving hand maximizes trunk rotation; have the patient inhale during the movement, hold, and cough while throwing the trunk and arm down toward opposite knee. When devising the most appropriate self-assisted cough for your patient, remember to look for a combination of trunk, arm, head, neck, and eye patterns that will maximize all four phases of the cough.

Hands-Knees, Rocking Self-Assisted Cough

The last assistive cough to be discussed is performed most commonly as a multipurpose activity to increase the patient’s balance, strength, coordination, and functional use of breathing patterns (including quiet breathing and coughing) simultaneously. The patient assumes an all-fours position (hands-knees). He or she is then instructed to rock forward, looking up and breathing in while moving to a fully extended posture (Figure 22-10, A). After this, the patient is told to cough out as he or she quickly rocks backwards to the heels with a flexed head and neck (Figure 22-10, B). Once again, note the importance of the flexion and extension components of the cough. The rocking can be done with or without a therapist’s assistance. For patients with generalized or spotty weakness throughout (e.g., some patients with SCI, head trauma, Parkinson disease, MS, cerebral palsy, or spina bifida), this method is perfect for incorporating many functional goals into a single activity. It can help prepare them for the more challenging respiratory activities they will undoubtedly face after their discharge from a rehabilitation center.

CoughAssist Machine

The CoughAssist, previously known as the Cofflator or Mechanical Insufflator-Exsufflator (MI-E), is a noninvasive machine used for airway clearance. A positive-pressure phase (insufflation) is followed by a negative pressure phase (exsufflation), simulating a cough. This device can be used as a face mask or attached to a universal adaptor for a tracheostomy tube (Figure 22-11).

Adults and children with neuromuscular disease are susceptible to recurrent chest infections, which are a major cause of morbidity and mortality. The suggested mechanism of action of the CoughAssist machine is to improve peak cough flow.19 In a study of 22 patients ages 10 to 56 (median age 21), spirometry and respiratory muscle strength were measured. Peak cough flows were measured with maximal coughs unassisted, then randomly with assistive coughs, noninvasive mechanical ventilation, CoughAssist machine, and exsufflation alone. All the therapeutic techniques were well tolerated and showed similar patient acceptance. However, the CoughAssist machine produced greater increases in cough pressures than did the other cough-assist techniques.23 Considering the workload of caregivers and the availability of the CoughAssist machine, many patients with neuromuscular weakness and artificial airways could well use this as an effective adjunct in the home, as well as in other settings.

The CoughAssist machine has been used primarily in adults, but it is being used more and more in children. In a study of 62 children (median age 11.3, ranging from 3 months to 28.6 years) with neuromuscular disease and impaired cough who were seen in a pediatric respiratory clinic, it was much preferred and was considered safe, well tolerated, and effective in 90% of this population for preventing pulmonary complications.36 In a similar study, patients with spinal cord injury also preferred the CoughAssist machine and found it effective and more comfortable than other methods for removing secretions.37 In a direct comparison of suctioning and the CoughAssist machine for adult patients with neuromuscular impairments, Massery and colleagues found no clinically significant difference between the two mechanical interventions; however, patients preferred the CoughAssist machine 10 to 1 over suctioning.38